Source: Link

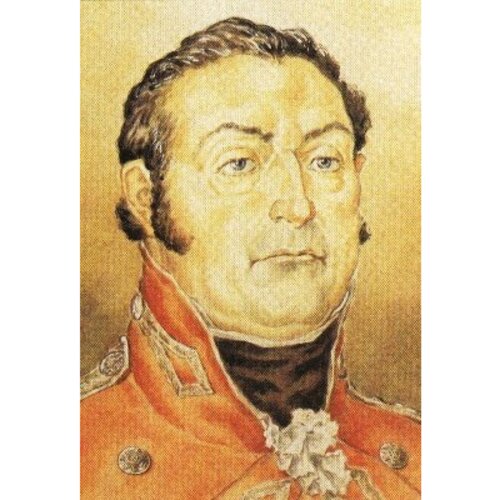

PROCTER (Proctor), HENRY, army officer; b. c. 1763 in Ireland, eldest son of Richard Procter and Anne Gregory; m. 1792 Elizabeth Cockburn in Kilkenny (Republic of Ireland), and they had one son and four daughters; d. 31 Oct. 1822 in Bath, England.

The son of a British army surgeon who was at the battle of Bunker Hill, Henry Procter entered the 43rd Foot as an ensign on 5 April 1781. He obtained a lieutenancy that December, and served around New York in the closing stages of the War of American Independence. A captain from November 1792 and a major from May 1795, he exchanged into the 41st Foot as a lieutenant-colonel on 9 Oct. 1800 and joined the regiment in Lower Canada two years later. His record as a commanding officer was praised by his superiors, including Major-General Isaac Brock*, who in 1811 ascribed the excellent condition of the 41st to the “indefatigable industry” of Procter.

After the outbreak of hostilities with the United States in the summer of 1812 Brock sent Procter, by then a colonel, to take command at Amherstburg, Upper Canada, which was threatened by an American army from Detroit. In August Procter took steps to cut communications between Detroit and the Ohio settlements. The resulting skirmishes at Brownstown (near Trenton, Mich.) and Maguaga (Wyandotte, Mich.) isolated the Detroit garrison and contributed substantially to its capitulation on the 16th to forces led by Brock. Procter remained as commander on the Detroit frontier after Brock’s departure, and in September he sent an expedition under Captain Adam Charles Muir against Fort Wayne (Ind.). By the end of the year an American army under Brigadier-General William Henry Harrison was en route to Detroit. On 19 Jan. 1813 Procter received news that its advance guard had occupied Frenchtown (Monroe, Mich.) on the River Raisin. He immediately launched an expedition which attacked and forced the surrender of the advance guard. As a consequence Procter was appointed brigadier-general (he would be promoted major-general in June) and the House of Assembly of Upper Canada passed a vote of thanks. On the other hand, he was accused by the Americans of failing to prevent the murder of some prisoners by his Indian allies after the battle.

Harrison had retreated upon hearing the news of Frenchtown, but by May 1813 he had established himself on the Maumee River at Fort Meigs (near Perrysburg), Ohio. Conscious of his own inferiority in numbers, Procter decided to attack the fort before American reinforcements could arrive. A relief column was successfully ambushed on the 5th, but Procter was unable to take the fort itself and withdrew on the 9th. Two months later, in response to Indian demands, he made a second and equally abortive attempt on Fort Meigs before thrusting at Fort Stephenson (Fremont), Ohio, on the Sandusky River. The failure of the latter assault cost the British many casualties.

The losses were especially unfortunate in view of the lack of adequate reinforcements and supplies, a result of the low priority of the Detroit frontier and the long and uncertain lines of communication. More important, these deficiencies also affected the British squadron on Lake Erie under Robert Heriot Barclay*, and the outcome of the campaign of 1813 on the Detroit frontier hinged on control of the lake, where by the summer the Americans were completing their own squadron. Procter was well aware of the situation, and he and Barclay proposed an attack on the American naval base of Presque Isle (Erie), Pa. Major-General John Vincent* was willing to send the necessary forces from the Niagara peninsula, but when Major-General Francis de Rottenburg assumed command he refused any aid.

The lack of sufficient troops and supplies continued to plague Procter during the summer, and Barclay’s defeat in the battle of Lake Erie in September gave the Americans total command of the lake. Procter had little chance of halting the expected invasion without substantial reinforcements, which could no longer be sent to him. A withdrawal would, however, be difficult, for it would risk a rupture with the Indians, who were still anxious to attack the Americans [see Tecumseh*]. Such a break would not only result in the loss of allies who had been extremely valuable but might also expose all the settlements west of the Niagara frontier to attack by the disgruntled Indians as well as the Americans.

Procter planned to withdraw up the Thames valley, thus extending the enemy lines of communication and keeping his own forces well away from Lake Erie. The retreat from Amherstburg and Sandwich (Windsor) began on 27 September, those stores which could not be transported being destroyed. On 5 October, however, the pursuing Americans caught up at present-day Thamesville, and in the ensuing battle of Moraviantown Tecumseh was killed and the British troops were captured or scattered. Procter with a few survivors fled the scene and continued the retreat to Ancaster.

Controversy about the retreat and the battle began almost as soon as the fighting ended. Procter’s staff adjutant of militia, John Christopher Reiffenstein*, who had left the action before his commander, spread the most alarming and exaggerated reports of the battle and Procter’s conduct. Rottenburg and Lieutenant-General Sir George Prevost*, the commander of the forces, attempted to dissociate themselves from any responsibility for the defeat, though it is clear that hunger, fatigue, and lack of supplies had left the British troops in no condition to fight successfully even under inspired leadership. It remains a fact, however, that Procter’s leadership was less than inspired.

Because of the defeat, Prevost refused to employ Procter elsewhere. For various reasons it was not until December 1814 that a court martial in Montreal began hearings. Procter faced five charges: first, that he did not begin his retreat sufficiently soon; second, that he allowed the retreat to be slowed by taking too much baggage, some of it personal; third, that he did not take appropriate measures to prevent supplies and ammunition from falling into enemy hands; fourth, that he neglected to fortify adequately positions along the Thames, in particular at the forks of the river (Chatham); fifth, that he made poor dispositions to meet the enemy at Moraviantown and failed to rally and encourage his troops and Indian allies at and after the battle. The court found him innocent of the first charge and guilty or partially guilty of the others, sentencing him to be reprimanded publicly and suspended from rank and pay for six months. When reviewed by the British judge advocate general and the Prince Regent, the findings of the court were confirmed on all but the second charge, on which grounds for conviction were found wanting. The sentence was reduced to a simple reprimand, but this was still sufficient to ruin Procter’s career. He nevertheless remained in the Canadas until the fall of 1815, when he returned to England to live the remainder of his life in semi-retirement.

In Canadian historical writing Procter has almost always been condemned as a failure, not only for his final defeat but also for his actions on the Sandusky, Maumee, and Raisin rivers. John Mackay Hitsman, for example, concluded that of British generals “only Procter managed to blunder consistently.” Often, though not in Hitsman’s case, the censure seems to derive mainly from John Richardson*’s vitriolic criticism, which was apparently caused by Procter’s failure to praise sufficiently Richardson’s role in the fighting on the Maumee River. Certainly his conduct prior to the withdrawal from the Detroit frontier in September 1813 is beyond reproach. Moreover, relatively few accounts take enough note of the difficulties under which Procter operated, or of the fact that the charges against him were so general that it was obvious he would be found guilty on some. Perhaps the most charitable as well as the most accurate judgement has been made by Pierre Berton, who claims that “to the Americans he remains a monster, to the Canadians a coward. He is neither – merely a victim of circumstances, a brave officer but weak, capable enough except in moments of stress, a man of modest pretensions, unable to make the quantum leap that distinguishes the outstanding leader from the run-of-the-mill.”

PRO, WO 91/9–10. Defence of Major General Proctor, tried at Montreal by a general court martial upon charges affecting his character as a soldier . . . (Montreal, 1842). Doc. hist. of campaign upon Niagara frontier (Cruikshank). Documents relating to the invasion of Canada and the surrender of Detroit, 1812, ed. E. A. Cruikshank (Ottawa, 1912). [John] Richardson, Richardson’s War of 1812; with notes and a life of the author, ed. A. C. Casselman (Toronto, 1902). Select British docs. of War of 1812 (Wood). [J.] B. Burke, A genealogical and heraldic history of the landed gentry of Great Britain (12th ed., London, 1914). G.B., WO, Army list, 1781–1816. Officers of British forces in Canada (Irving). The royal military calendar, containing the service of every general officer in the British army, from the date of their first commission . . . , ed. John Philippart (3v., London, 1815–[16]). Pierre Berton, Flames across the border, 1813–1814 (Toronto, 1980). Hitsman, Incredible War of 1812. Reginald Horsman, The War of 1812 (London, 1969). D. A. N. Lomax, A history of the services of the 41st (the Welch) Regiment (now 1st Battalion the Welch Regiment), from its formation, in 1719, to 1895 (Devonport, Eng., 1899). E. A. Cruikshank, “Harrison and Procter; the River Raisin,” RSC Trans., 3rd ser., 4 (1910), sect.ii: 119–67. [C. O. Z.] Ermatinger, “The retreat of Proctor and Tecumseh,” OH, 17 (1919): 11–21.

Cite This Article

A. M. J. Hyatt, “PROCTER (Proctor), HENRY,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 6, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/procter_henry_6E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/procter_henry_6E.html |

| Author of Article: | A. M. J. Hyatt |

| Title of Article: | PROCTER (Proctor), HENRY |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 6 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1987 |

| Year of revision: | 1987 |

| Access Date: | February 1, 2026 |