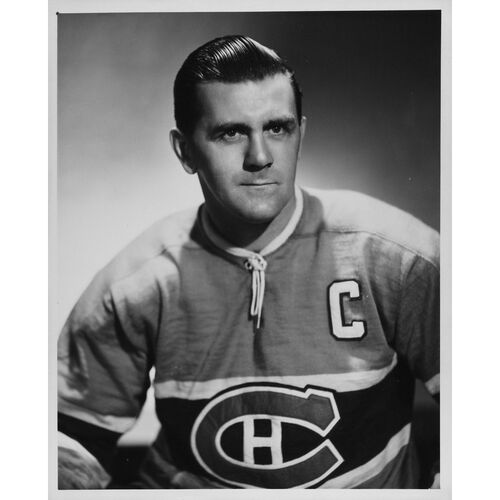

![Maurice Richard, [Entre 1951 et 1997], BAnQ Vieux-Montréal, Fonds Antoine Desilets, (06M,P697,S1,SS1,SSS11,D27), Antoine Desilets. Original title: Maurice Richard, [Entre 1951 et 1997], BAnQ Vieux-Montréal, Fonds Antoine Desilets, (06M,P697,S1,SS1,SSS11,D27), Antoine Desilets.](/bioimages/w600.24963.jpg)

Source: Link

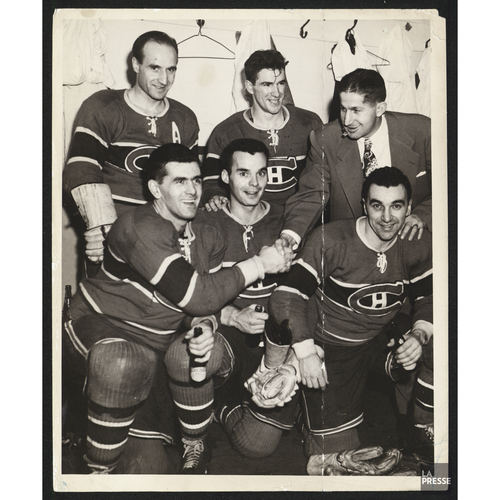

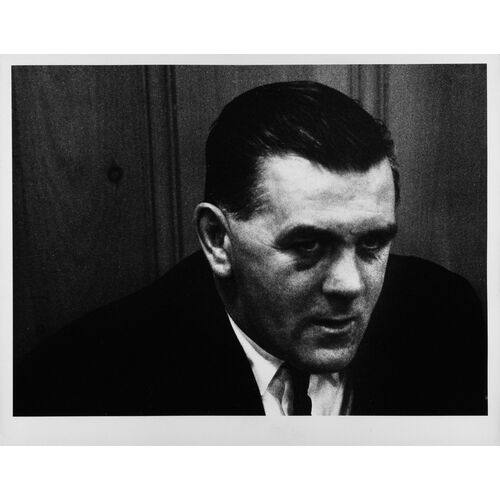

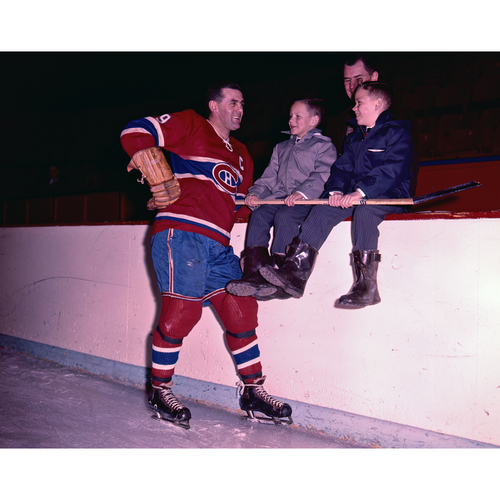

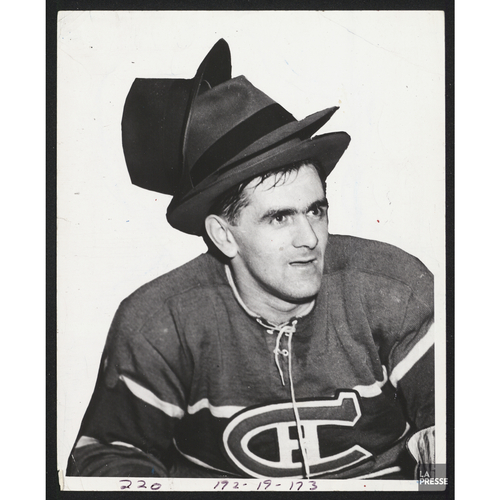

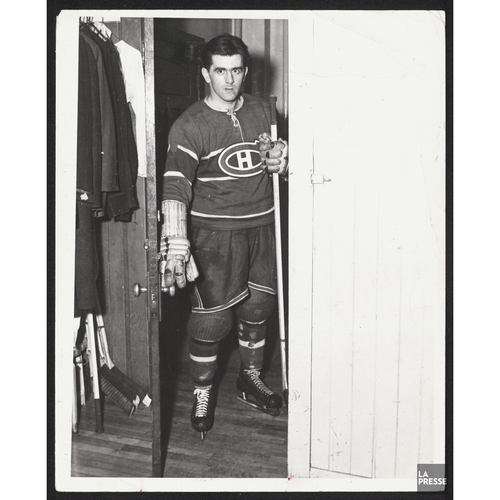

RICHARD, MAURICE (baptized Joseph-Henri-Maurice), known as the Rocket, professional hockey player, machinist, and shopkeeper; b. 4 Aug. 1921 in Montreal, eldest of the eight children of Onésime Richard and Alice Laramée; m. 12 Sept. 1942 Lucille Norchet (d. 1994) in Montreal, and they had five sons and two daughters; d. 27 May 2000 in Montreal.

Maurice Richard came from a family of modest means. His parents, who were born in the Gaspé, moved to Montreal after their marriage. Maurice grew up in the Bordeaux district, near Ville Saint-Laurent (Montreal), and got his start in hockey there, first with his school team, and then with the neighbourhood one. While he was studying at the Montreal Technical School to become a machinist, Maurice played on the Parc Lafontaine teams. He had such obvious talent that a number of other sides wanted to get the left-winger for their ranks. Since he could not be on more than one team in a given year, he decided to use various names – that way, he could play hockey every day. The world of junior hockey discovered him in 1937–38. He was then playing on Paul-Émile Paquette’s team, with Georges Norchet (who would become his brother-in-law) as captain and Paul Stuart as coach. Stuart advised his colleague Arthur Therrien, the trainer of the Verdun Maple Leafs, to meet the young player, with the result that Richard was able to make his mark with this team during the 1938–39 and 1939–40 seasons.

In 1940–41 Richard signed a contract with the Montreal Senior Canadiens, the farm team for the great National Hockey League (NHL) club of the same name. In two seasons he played only a few games because he suffered two fractures (one to his wrist, the other to his ankle). His coach, Paul Haynes, did, however, have time to observe that he had an excellent back hander, even when playing left wing, and to change him into a right winger.

Events moved quickly in 1942. First of all, he found a job at the Angus Shops, where his father was working as a machinist. For several years he would work at this job over the summer. He tried to enlist in the army, but was turned down because of injuries he had incurred. In September, a few days before his marriage to Lucille Norchet, he signed his first professional contract with the Montreal Canadiens (known in English Canada as the Habs, for Habitants). At the time he began his initial season in the NHL, the league had just undergone two important changes. Between 1926 and 1931 it had ten teams. The depression, followed by World War II, forced four to withdraw. These were: in 1931 the Pittsburgh Pirates of Pennsylvania (founded in Philadelphia as the Quakers for the 1930–31 season); in 1935 the Ottawa Senators (founded in St Louis, Mo., as the Eagles for the 1934–35 season); in 1938 the Montreal Maroons; and in 1942 the New York Americans (called the Brooklyn Americans during the 1941–42 season). For 25 consecutive seasons there would be only six teams: the Chicago Blackhawks (incorrectly written as two words, Black Hawks, until 1986), the Boston Bruins, the Montreal Canadiens, the Toronto Maple Leafs, the New York Rangers, and the Detroit Red Wings. Many experts think that the addition of a red line at centre ice, in 1942–43, marked the beginning of modern professional hockey. Since 1919–20 there had been two blue lines, and forward passes had been permitted within each zone, but in order to move the puck across the blue line a player had to have possession of it. With the addition of the red line, passing was permitted from behind the net and across the blue line, as far as centre ice. The 1942–43 season ended early for Richard when he broke his ankle on 27 December. Despite the five goals and 11 points he had accumulated in 16 games, his frailty was causing some concern among fans of the Canadiens.

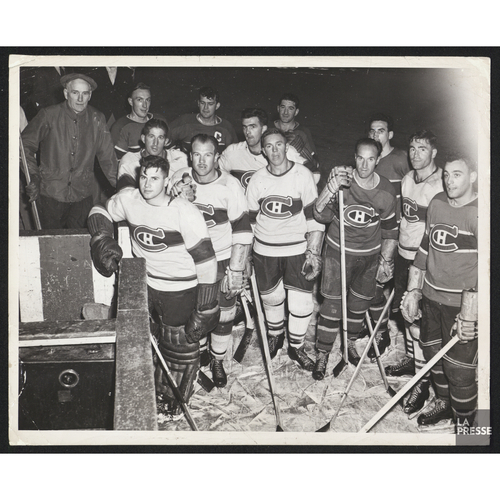

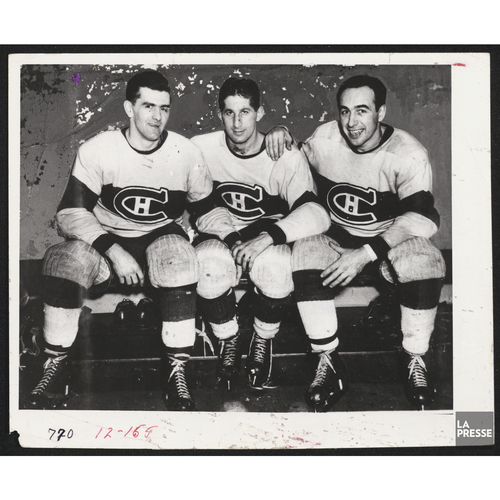

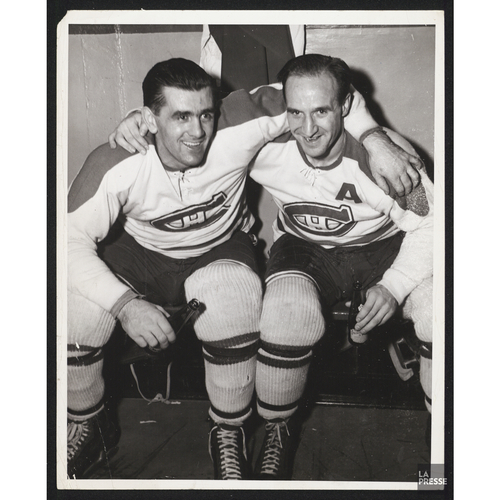

In the next season, Richard came back stronger than ever. He was wearing a new number – 9 instead of 15 – in honour of his daughter Huguette, who weighed nine pounds at birth. His team-mate Raymond Getliffe, who was astonished by the speed with which Richard outplayed him and his linemates Phillip Henri Watson and Erwin Groves (Murph) Chamberlain during practices, nicknamed him the Rocket. Together with Hector (Toe) Blake and Elmer Lach (with whom he made up the famous Punch Line), he scored 32 goals in 46 games. In the playoffs, he helped his team win the Stanley Cup against the Blackhawks by getting 12 goals in nine games. This was the fifth Stanley Cup the Habs had won, but the first since 1930–31. The five-foot-ten, 195-pound Rocket was now a star. Of all the players, he was the most determined to score. Between the blue line and the net, virtually nothing could stop him. The goalies could see the fire in his eyes as he skated towards them. Anyone who got in his way risked reprisals; he did not hesitate to retaliate with his fists, or even his stick.

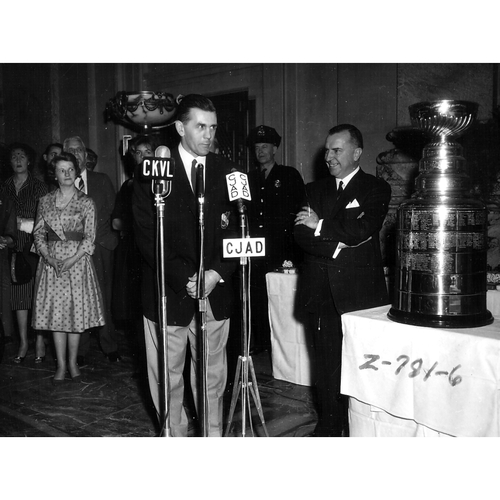

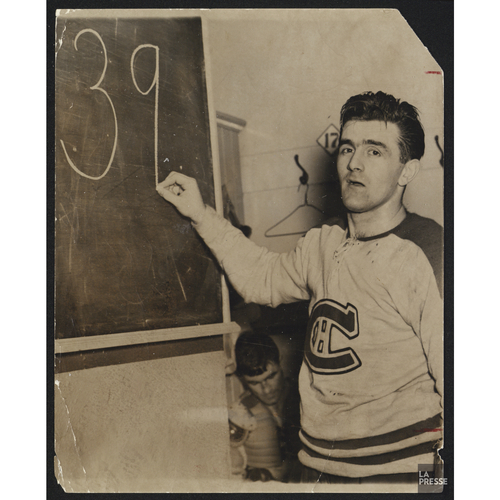

The Punch Line set other records in 1944–45. Lach, with 80 points, was the highest scorer in the NHL; Blake had 67. The line achieved 220 points that season. The Rocket registered 50 goals in 50 games, surpassing the 44 goals in 20 games scored by Maurice Joseph Malone in 1917–18. Since it was wartime, however, a number of journalists took a dim view of these records. Constantine Falkland Cary Smythe*, the owner of the Maple Leafs, had raised a regiment and encouraged hockey players to enlist, with the result that during World War II the Toronto club lost more than half its players. For the Canadiens, the situation was different, and consequently tongues began to wag. The Montreal team was said to be taking advantage of the war to pile up victories. The results of the following seasons gave the lie to this impression. Even with the soldiers home again, the Habs won the Stanley Cup against the Bruins in 1945–46. Richard scored 27 goals in season play and 7 in the playoffs. In 1946–47 he scored 45 goals and was awarded the Hart Trophy as the most valuable player. His detractors had to accept the reality and applaud him. Even Conn Smythe admitted that Richard was the best player, and he would make several attempts to buy his contract from the Canadiens, offering up to $135,000.

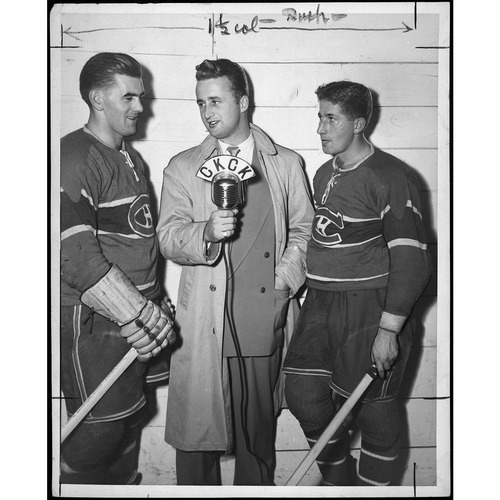

During the 1950s the Canadiens reigned supreme in the NHL and the Rocket’s popularity soared. The Montreal club was in the Stanley Cup finals ten years in a row, and won it six times. The advent of television enabled both French- and English-speaking Canadians, who all knew Richard, to see him in action and breaking records. On 8 Nov. 1952, for example, he scored the 325th goal of his career against Chicago, beating the record of 324 set by a former Maroons player, Nelson Robert Stewart. In 1953–54 he also wrote a hockey column for the Montreal weekly Samedi-dimanche. In one of his pieces, he commented on what he considered an unfair decision by Clarence Campbell*, president of the NHL, with regard to Bernard (Boom Boom) Geoffrion*. The pressure exerted by Campbell – who for many people represented the Montreal English-speaking and anti-French establishment – to stop Richard from writing his column had its effect. On the eve of the most important event in the Rocket’s career, the tension between the two men reached its peak.

On 13 March 1955, during a game in Boston, a fight broke out between Richard and Harold Richardson Laycoe. When Richard saw that his head was bleeding, he was furious, and he rushed at Laycoe, brandishing his stick. The linesmen intervened, and one of them, Clifford B. Thompson, held Richard from behind while Laycoe continued to hit him. In an effort to break loose, Richard turned and struck the linesman. Richard said afterwards that he thought it was a Bruins player who was holding him. Such a mistake was possible because the officials at that time wore beige sweaters that were similar to the Bruins’ yellow ones. In fact, as Richard later admitted, he knew who was holding him, but he was not prepared to let himself be pushed around. The following season, the officials wore striped sweaters.

Two days later Richard had a meeting with Campbell to explain himself. It looked bad for the Rocket, who had already been suspended for several games at the beginning of the season as the result of another fight. Campbell gave his verdict on 16 March. Richard would be off the ice for the rest of the season, which included the last three games of the regular season and all of the playoffs. The Montreal French-language press screamed that it was an outrage. Richard would never accept this decision; in his opinion, the suspension – even if it had to be carried over to the next season – should not have affected the playoffs.

In Montreal the next game of the regular season, scheduled for 17 March, between the Canadiens and the Red Wings, thus promised to be stormy. The mayor of Montreal, Jean Drapeau, even urged Campbell not to attend, fearing that his presence might provoke people’s anger. A crowd had gathered at the entrance to the Montreal Forum before the game started. Many people were carrying placards denouncing Campbell. Shortly after the puck was dropped, Campbell arrived with his secretary (and future wife). Things were thrown at them. When Campbell stood up at the end of the first period, a spectator tossed a tomato, which hit him in the face. A few seconds later, a tear-gas bomb went off near him. The crowd rushed for the exits. Campbell took refuge in the referees’ dressing room, where he met the Rocket. He asked Frank J. Selke, the general manager, to close the Forum and declare the game defaulted. The contest, which the Canadiens lost 4–1, was the shortest in the history of the NHL. Outside, a riot broke out. The windows of the Forum were smashed and the crowd swarmed into Rue Sainte-Catherine, where they vandalized a number of stores. Only the Rocket’s statement on the radio the next morning cooled the anger of his fans. A number of scholars maintain that this exceptional demonstration of national pride was the prelude to the Quiet Revolution. In the playoffs, the Canadiens bowed to the Red Wings, who won the Stanley Cup in seven games. As for Richard, he lost his last chance to win the title of high scorer for the regular season, which went that year to Geoffrion.

The Canadiens began the 1955–56 season with a new coach, Toe Blake, who replaced James Dickenson Irvin, and a new recruit, Henri Richard, who was the Rocket’s brother. Another brother, Claude, would also try to join the Canadiens, but without success. Until 1959–60 the team would dominate the NHL in an extraordinary way, with five successive Stanley Cups and four Prince of Wales Trophies, awarded to the team finishing first in the NHL overall. Richard played an active part in these victories, but was slowed down again by injuries. During these years of triumph, there were few changes in the team’s makeup; 12 players – nicknamed the 12 Apostles – remained at their posts, as did their coach. On 19 Oct. 1957, in a game against Chicago, Richard outmanoeuvred goalie Glenn Henry Hall to score his 500th career goal. He dedicated it to Dick Irvin, who had died a few months earlier.

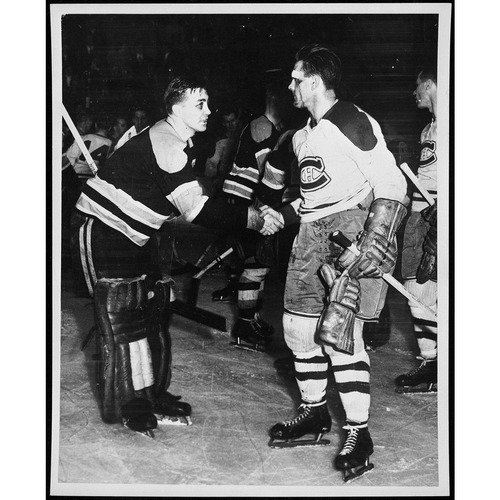

On 15 Sept. 1960 Richard officially announced his retirement. His heart was no longer in it and his body was tired. Nevertheless, the list of his NHL records – nearly 20 – is impressive: the most career goals (544) and hat tricks (26); the most goals in one season (50); and the most goals (82), winning goals (18), and overtime goals (6) in playoff games. These exploits show what a dominant player the Rocket had been at critical moments, especially in the two series that then made up the Stanley Cup playoffs, which the Canadiens had won eight times during the years when Richard was on the team. It was certainly because of his talent and determination that the Rocket had such success, but the cooperation of his many team-mates – Lach, Blake, Jean Béliveau*, Geoffrion, Richard Moore, his brother Henri – also worked in his favour. Defencemen Émile (Butch) Bouchard* and Doug Harvey, as well as goalies William Arnold Durnan and Jacques Plante, who concentrated on stopping an opponent, made Richard’s attacks easier.

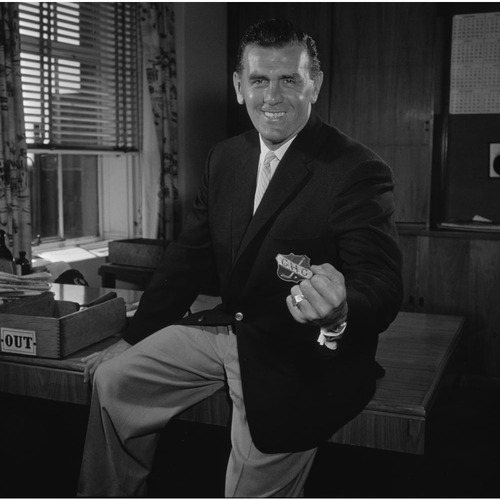

Richard did, however, remain with the Canadiens, where he held a position as representative for various social functions. Since his contract had not expired, he was supposed to receive his full salary – about $25,000 – for three more years. He spent two years travelling across North America, after which, at his own request, his duties were reduced. Despite the promise that had been made to him, he was then paid only half his salary. Around 1965 he finally slammed the door. Only a change within the organization in 1981 would persuade him to rejoin the clan as an ambassador for the Canadiens.

Richard launched into business. First he bought a pub in downtown Montreal, and then he sold it three years later for twice what he had paid for it and reinvested the money in a fishing-line business, which he set up in his basement. As a celebrity, he was asked to participate in various sporting and other events in Canada, the United States, and sometimes Europe. During the 1980s he would write a sports column for Montreal’s La Presse.

In 1971 the World Hockey Association was founded to compete with the NHL. One franchise, the Nordiques, was granted to Quebec City the following year. Marius Fortier, one of the six founders of the team, offered Richard a job as its coach. The Rocket, who saw this as a chance to fulfil a long-standing dream, accepted, but with the proviso that he would be able to spend every fall hunting. He reached an agreement with the Nordiques whereby Maurice Filion would run the training camp and he would take over as coach at the beginning of the regular 1972–73 season. The famous former player showed up on 11 October for the first game in the club’s history, against the Crusaders at Cleveland, Ohio. The Nordiques lost, 2–0. Realizing that he did not have the temperament required, he handed in his resignation, but was persuaded to stay on for one more game. And so, Richard’s coaching career ended two days later, after the Nordiques’ first home game, against the Alberta Oilers. The Nordiques won 6–0.

The Rocket received many honours. He was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame in 1961, although a player usually had to wait five years after retirement to be given such recognition. Furthermore, the Canadiens immediately retired the number 9. Richard was the second player in the club, after Howard William Morenz*, number 7, to earn this mark of esteem. Among his other distinctions were the opening of an arena named after him in Montreal in 1962 (a museum devoted to his career would be inaugurated there in 1996) and his election to Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame and to the Panthéon des Sports du Québec. A plaque bearing his name has even been installed in the hall of fame of Madison Square Garden in New York. He was named to the Queen’s Privy Council for Canada in 1992 and became an officer of the Order of Canada in 1967 and a companion in 1998; in 1985 he was made an officer of the Ordre National du Québec. He also inspired numerous works, including a biography by Jean-Marie Pellerin, a song by Pierre Létourneau, and a memoir by Roch Carrier.

The honours bestowed on the Rocket culminated in the ceremonies at the closing of the Montreal Forum and the creation of the Maurice Richard Trophy. On 11 March 1996 the building that the Canadiens had occupied continuously since 1926 shut its doors. The team used the occasion to organize a special event at which the members of the Hockey Hall of Fame (including Butch Bouchard, Jean Béliveau, Guy Lafleur*, and Robert M. Gainey) and former captains were introduced. Bouchard carried the torch, and then passed it to Richard, who had succeeded him as captain in 1956. The crowd gave him a standing ovation that went on for nearly 15 minutes. On the giant screen at the centre of the rink, the Rocket was weeping. Most of those present – some 18,000 – had never seen Richard play, since he had retired 36 years earlier, but they all knew the Rocket, had heard their parents and grandparents tell of his exploits, had seen pictures of the fiery-eyed player in action. At the end of the 1998–99 season Teemu Selanne, of the Mighty Ducks of Anaheim, Calif., received the Maurice Richard Trophy. He was the first winner of this award, presented to the highest scorer of the season in the NHL, and established in honour of the Rocket (who would have won it five times himself, had it existed during his playing career.)

On the morning of 27 May 2000 Maurice Richard lost his fight with cancer. The Molson Centre in Montreal became a chapel of rest where some 100,000 people came to pay homage to him. The funeral, held on 31 May in Notre-Dame basilica, was attended by thousands of admirers. Former team-mates, including his brother Henri, carried the Rocket’s coffin, while veterans of the Canadiens, prominent politicians, and former opponents, such as Gordon Howe* and Robert Blake Theodore Lindsay, who had played for Detroit, followed the funeral procession. But the man for whom all these people had come together had always said, throughout his life, that he was just a hockey player, nothing else.

Soc. de Généalogie de Québec, Fichier Drouin, Saint-Denis (Montréal), 6 août 1921. Le Soleil (Québec), 28 mai 2000. Gérard Binette, Mariages de Notre-Dame du Très Saint-Sacrement (Montréal), 1926-1990 (Montréal, 1992). Roch Carrier, Our life with the Rocket: the Maurice Richard story, trans. Sheila Fischman (Toronto, 2001). Chrys Goyens et al., Maurice Richard, reluctant hero (Toronto, 2000). “Maurice Richard talks about . . . the Rocket,” Les Canadiens: Hockey Magazine (Montreal), 9 (1993–94), no.7: 22–66. Claude Mouton, Toute l’histoire illustre et merveilleuse du Canadien de Montréal (2e éd., Montréal, 1986). Andy O’Brien, Rocket Richard (Toronto, 1961). Rolland Ouellette, Les 100 plus grands Québécois du hockey (Montréal, 2000). J.-M. Pellerin, L’idole d’un peuple: Maurice Richard (Montréal, 1976). Total hockey: the official encyclopedia of the National Hockey League, ed. Dan Diamond (Toronto, 1998).

Revisions based on:

“Hockeydb.com: the Internet hockey database”: www.hockeydb.com (consulted 25 July 2016). Sports Reference, “Hockey reference”: www.hockey-reference.com (consulted 27 July 2016). National Hockey League, “NHL.com”: www.nhl.com/en (consulted 27 July 2016).

Cite This Article

Michel Vigneault, “RICHARD, MAURICE (baptized Joseph-Henri-Maurice), known as the Rocket,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 22, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 19, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/richard_maurice_22E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/richard_maurice_22E.html |

| Author of Article: | Michel Vigneault |

| Title of Article: | RICHARD, MAURICE (baptized Joseph-Henri-Maurice), known as the Rocket |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 22 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2016 |

| Access Date: | February 19, 2026 |