Source: Link

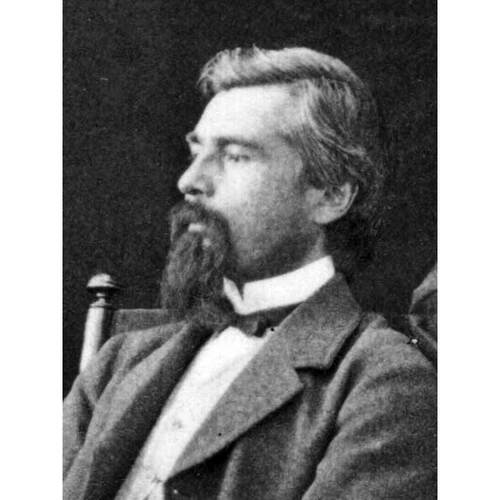

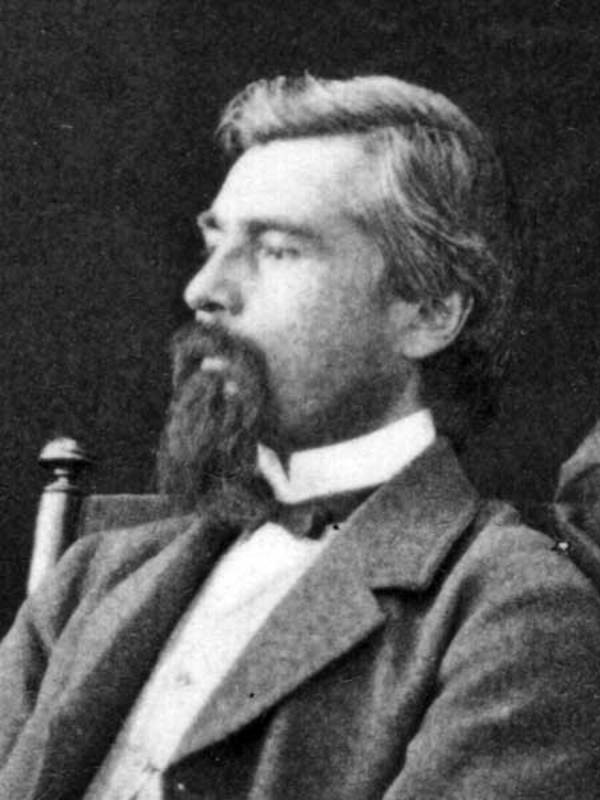

ROSS, JAMES, teacher, public servant, journalist, and lawyer; b. 9 May 1835 at Colony Gardens, the family house in Red River Settlement, son of Alexander Ross*, former chief trader of the Hudson’s Bay Company, and Sarah, who may have been a daughter of an Okanagan Indian chief; d. 20 Sept. 1871 probably at Colony Gardens.

James Ross was educated at Red River and at Toronto. The Reverend David Anderson*, bishop of Rupert’s Land, later wrote that Ross was “a distinguished scholar at the Red River College of St. John’s . . . who afterwards went through a very creditable academic career at the University of Toronto.” He entered the university on a scholarship in 1853, received awards each year, and upon graduation in 1857 won three medals, two gold and one silver. For a brief time after graduation Ross seriously considered entering the Presbyterian ministry, but an opportunity to teach at Upper Canada College changed his mind. However, the death of an older brother, William, in 1856, followed by the death of his father in the same year, left the affairs of his family in a tangled condition. Ross and John Black, the two executors, disagreed about the settlement of the estates and Ross was forced to return to Red River. Before leaving Toronto, Ross married Margaret Smith on 18 May 1858; five children were born of this marriage. Upon his arrival at Red River Ross found himself confronted by extremely complex family problems and, though he did his best to resolve them, these problems plagued Ross and complicated his relations with other members of the family until his death. Shortly after his return, on 12 May 1859, Ross was appointed postmaster of the Assiniboia at a salary of £10 per annum.

In 1860, Ross joined his brother-in-law, William Coldwell, and William Buckingham, two former Toronto journalists, as part owner and an editor of the Nor’Wester, the first newspaper in the Red River Settlement. In October 1860 Buckingham withdrew and Ross’ interest in, and work for, the Nor’Wester increased. During 1861 the Nor’Wester published, in 16 instalments, “History of the Red River Settlement,” written by Ross, a work of considerable interest for it contains much information about the settlement which is not readily accessible elsewhere. Not long after Ross joined the Nor’Wester, the paper carried an editorial criticizing the Hudson’s Bay Company and the system of government at Red River. As a result, Ross and the paper were identified with the “Canadian party.” This did not, however, prevent the Council of Assiniboia from appointing Ross sheriff and governor of the gaol in the spring of 1862. But Ross continued to antagonize the local authorities.

During the summer of 1862 the Sioux massacred many American settlers; to avoid reprisals by American troops they fled into British territory and encamped not far from the Red River Settlement. Their presence caused much alarm in the settlement. Under these circumstances the Council of Assiniboia circulated a petition calling for the imperial government to send out troops for the protection of the settlers. In the Nor’Wester Ross immediately launched a counter-petition, not only calling upon the imperial government to dispatch troops to Red River but also requesting “such changes in the system and administration of the local government as will remove the present discontent and dissatisfaction . . . .” This was too much; by a unanimous vote of the council on 25 November, Ross’ appointments as postmaster, sheriff, and governor of the gaol were terminated. Ross, however, continued his attacks; a number of meetings were held at which he denounced the local government and urged the settlers to sign the counter-petition. Eventually Sandford Fleming* forwarded the counter-petition to the colonial secretary, the Duke of Newcastle [Henry Clinton].

Ross again identified himself with the antigovernment forces during the trial of the Reverend Griffith Owen Corbett*. Corbett, who had supported the counter-petition, was brought to trial on the charge of having attempted to perform an illegal operation upon his maid servant. Ross saw in this the persecution of Corbett for the latter’s opposition to the government and consequently played a leading role in the defence of Corbett, thereby adding to his reputation as an opponent of the existing government.

Ross’ association with the Nor’Wester had placed him squarely among the members of the Canadian party. When Ross withdrew from the Nor’Wester late in 1863, in anticipation of his return to Canada, the manner in which he withdrew reinforced his connection, for his place was soon taken by Dr John Christian Schultz* who was regarded by many as the leader of the Canadian faction at Red River.

Leaving his wife and children behind him, Ross departed from the settlement in the spring of 1864 and returned to Toronto to study law. Margaret and some of the children joined him when it became evident that his stay in the east would be a long one. On 5 July Ross became a clerk for John McNab, attorney, and in August of the same year he wrote and passed examinations for admission to the Law Society of Upper Canada. Ross pursued other studies also and in June of 1865 he received an ma from the University of Toronto.

While carrying on his studies Ross had to support his wife and family; not unnaturally he turned to journalism. Given his association with the Nor’Wester, Ross had little difficulty in establishing a connection with George Brown and the Globe; he maintained this connection until September 1864, when he accepted a position with the Hamilton Spectator which he held until the spring of 1865. At that time, having decided to settle permanently in Canada, Ross returned briefly to the Red River in order to clear up his personal affairs. Upon returning to Toronto in the late summer of 1865, Ross bought a house and went to work for the Globe. As a journalist in Canada from 1865 to 1869, Ross continued his attacks upon the HBC, and became known as a staunch proponent of the annexation of the company’s territories by Canada.

As his stay in Canada lengthened it became increasingly evident that Ross was unhappy; he was cut off from most of his family and from many of his friends; moreover, as his letters indicate, he became more and more concerned over the cost of living in Toronto. Then too, there were still disputes over his father’s estate which could only be resolved in the Red River Settlement. Late in the summer of 1869 Ross sold his house in Toronto and, accompanied by his family, he set out for the Red River. The early fall saw Ross back in Colony Gardens and thus in a position to play an important role in the dramatic events of 1869–70.

After Louis Riel* and his followers forced William McDougall*, the governor from Canada, to return to Pembina on 21 Oct. 1869, elections were held in all the Red River communities to choose representatives to consider Riel’s proposal for establishing a provisional government. James Ross was elected to represent the people of Kildonan. In the meetings which followed, Ross became “the spokesman for the English as definitely as Riel was for the French.” Ross and the majority of the English representatives did not sanction the establishment of a provisional government because they believed that such an act would be illegal. Instead they proposed that a more representative government, under the authority of the HBC, should be established. However, while Ross differed from Riel on the course of action to be taken, he firmly believed that it was essential for the English settlers to cooperate with the French in order to prevent the outbreak of civil war in the Red River. It is evident that his was a wise and statesmanlike position, and in adopting it Ross helped to prevent disaster overtaking the people of the settlement. But by taking this stand Ross found himself diametrically opposed to his former friends in the Canadian party; from their point of view Ross’ action was little short of treason, and they never forgave him for it.

Following the intervention of Donald Alexander Smith*, special commissioner from the Canadian government, it was proposed. that a convention, composed of representatives from each part of the settlement, should meet to discuss the terms on which the people of Red River would enter confederation. Ross was the unanimous choice to represent the parish of St John’s. The delegates met from 26 Jan. to 11 Feb. 1870, and selected Ross as a member of the committee of six chosen to draft the List of Rights. Throughout the debate which followed the presentation of the committee’s report, Ross was not only the leading spokesman for the English representatives, but served as translator of the speeches of the French delegates. Often he led the opposition to the proposals stemming from Riel’s suggestion that Red River should enter Canada as a province. Ross argued that it would be more in the interest of the people of Red River to enter as a territory and the convention supported him on this issue. But though the debate was often heated and emotional Ross’ efforts helped to prevent a complete break between the English and French representatives. Riel, as president of the provisional government, recognized the value of Ross’ efforts and appointed him chief justice in his administration.

It appears that Ross had been drinking heavily for some time and during this tense period his drinking increased; consequently for weeks in the late spring of 1870 Ross did little and he had no impact upon developments. In the late summer he went to Toronto, ostensibly on personal business, but his letters reveal that he wanted to be absent from the settlement when Colonel Garnet Joseph Wolseley*’s expeditionary force arrived. He was afraid that his actions during the previous winter might be misunderstood by the Canadians. He wrote his wife that he would return only after things had settled down and he suggested she state that his actions had been determined by his efforts to prevent bloodshed. While in Toronto, Ross took every opportunity to explain the policy he had followed during the critical days at Red River.

When Ross finally returned in the middle of October 1870, the newly established province was relatively peaceful. This was only a momentary lull before it was disturbed by both provincial and federal election campaigns in 1870 and 1871. Dr John Schultz was a candidate for the federal constituency of Lisgar, and Ross, convinced that the actions of Schultz during the winter of 1869–70 had nearly provoked civil war, threw himself into the campaign to oppose his election. First Ross supported Dr Curtis James Bird and campaigned vigorously to rally the old settlers behind Dr Bird. When the latter withdrew from the contest after being elected to the provincial assembly, Ross gave his support to Bird’s replacement, Colin Inkster. All Ross’ efforts were in vain, for Dr Schultz won an easy victory.

Courts were soon established in Manitoba, and Ross decided to return to the legal profession. On 8 May 1871, he became the third man to be admitted to the bar of Manitoba, but he had little opportunity to practise in the new province. In the tension of the election campaigns Ross had again taken to drink and during the summer his health began to decline rapidly. Pulmonary disease, of which there was a history in the family, may have caused his death.

PAM, Alexander Ross family papers; Church of England registers, St John’s Church (Winnipeg), baptisms, 1828–79, no.885. Begg’s Red River journal (Morton). Canadian North-West (Oliver), I, 442, 505–8. Hargrave, Red River. Manitoban (Winnipeg), 23 Sept. 1871. Nor’Wester (Winnipeg), 1860–63. The Canada directory, for 1857–58 . . . (Montreal, 1857), 808. Begg and Nursey, Ten years in Winnipeg. Careless, Brown, II, 7–8.

Cite This Article

W. D. Smith, “ROSS, JAMES (1835-71),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/ross_james_1835_71_10E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/ross_james_1835_71_10E.html |

| Author of Article: | W. D. Smith |

| Title of Article: | ROSS, JAMES (1835-71) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1972 |

| Year of revision: | 1972 |

| Access Date: | March 1, 2026 |