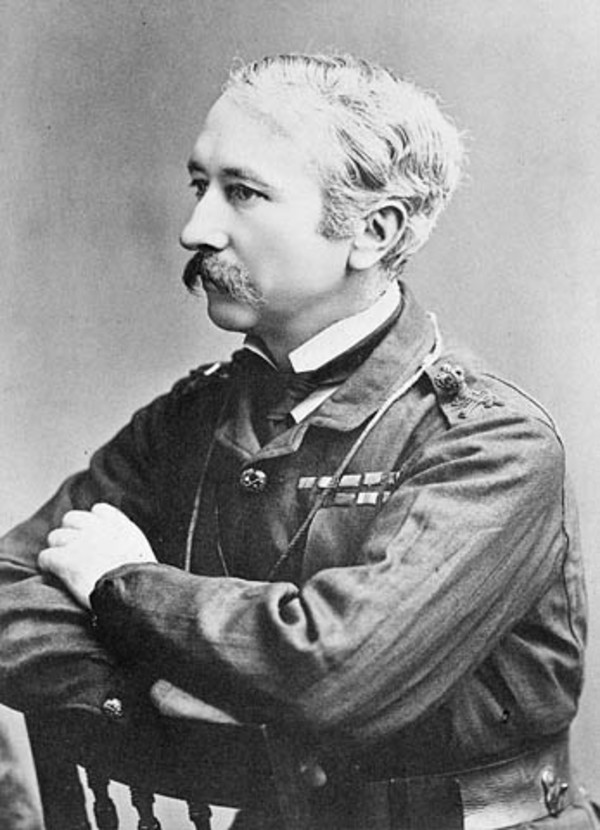

WOLSELEY, GARNET JOSEPH, 1st Viscount WOLSELEY, army officer; b. 4 June 1833 at Golden Bridge House, County Dublin (Republic of Ireland), eldest son of Major Garnet Joseph Wolseley and Frances Anne Smith; m. 4 June 1867 Louisa Erskine (d. 1920) in London, England, and they had one daughter; d. 25 March 1913 in Menton, France, and was buried in St Paul’s Cathedral in London.

Garnet Wolseley’s father died when he was seven and his mother brought up seven children in impecunious circumstances. Wolseley attended a day-school in Dublin and then worked in a surveyor’s office. On 12 March 1852 he was commissioned ensign in the 12th Foot, without purchase in recognition of his father’s career in the army. He soon transferred into the 80th Foot for service in India.

He was immediately thrown into colonial wars. In 1852–53 he was in Burma, where he was severely wounded in the thigh. He was mentioned in dispatches and was promoted lieutenant on 16 May 1853. Sent home to recover, he transferred to the 90th Light Infantry and was soon on his way to the Crimea. At Sevastopol (Ukraine), where he served throughout the siege of 1854–55, he was able to use his surveying knowledge as an assistant engineer and was again seriously wounded, losing the sight in his right eye. Wolseley would finish the war as deputy assistant quartermaster-general of the Light Division. Promoted captain, again without purchase, on 26 Jan. 1855, he was mentioned in dispatches several times, awarded the Legion of Honour, and recommended for the Victoria Cross.

Wolseley next served abroad in India, during the mutiny there. He led his company in the relief of Lucknow in November 1857 and ended the war as deputy assistant quartermaster-general to Major-General Sir James Hope Grant’s Oudh Division. Five times mentioned in dispatches during the campaign, he received his brevet majority on 24 March 1858 and a brevet lieutenant-colonelcy on 26 April 1859. Grant again requested his services on the quartermaster-general’s staff in the 1860 expedition to China. This campaign marked the end of Wolseley’s career as a regimental officer.

In 1861 Wolseley was posted to the Canadian command as assistant quartermaster-general at the time of the Trent crisis [see Sir Charles Hastings Doyle*], but he arrived, on 5 Jan. 1862, after the immediate threat of war with the United States had passed. In garrison in Montreal, he was drawn to amateur theatricals, to squiring the ladies, and to the study of military theory. Promoted full colonel on 5 June 1865, Wolseley had his first real experience with the Canadian militia that autumn when he was loaned to command the camp of instruction at La Prairie, near Montreal. The camp was designed to provide practical experience for the graduates of the schools of military instruction operated in Canada by the British army. It was inspired by Colonel Patrick Leonard MacDougall*, adjutant-general of the militia and military theorist, but the practical application was Wolseley’s. Each of the 1,105 officer-cadets who attended the three-week camp was “employed in turns upon all military duties, from that of regimental field officers down to that of private sentinels,” Wolseley wrote. In the concluding exercises, which involved the British garrison of Montreal, Wolseley was one of the brigade commanders, the first time he had commanded troops above the unit level. Much notice was taken of the activities of the camp. Most important, Sir John Michel*, lieutenant-general commanding in British North America, sent a favourable report to his superiors, noting, “It is difficult to speak too highly of this talented, energetic young officer.”

In June 1866, during the Fenian invasion of Upper Canada, the militia’s shaky response at Ridgeway [see Alfred Booker*] demonstrated many shortcomings in its training. A joint camp of observation and instruction was therefore set up at Thorold, with Wolseley as commandant. Volunteer units came to train for a week in company with British regulars, while at the same time the force protected the Niagara frontier. Again Wolseley imparted pragmatic instruction, his aim being “to afford officers and men instruction in the practical work which real war presents, and to avoid repeating drill-book manœuvres which never could be required in Canada.” Thorold was a useful experience. “This is capital practise for me as I am so little with troops & I can have much opportunity for learning how to handle men,” he wrote to his brother Richard. Moreover, the camp further brought him to the attention of those who mattered in Britain.

At the expiration of his appointment as assistant quartermaster-general Wolseley returned in April 1867 to England, where he was married, but he was called back in September as deputy quartermaster-general, at 34 the youngest officer ever to assume this senior staff post in Canada. His first years in Canada had marked the beginning of Wolseley the writer, with the publication of accounts of the war in China and of a visit he had made to the Confederate forces in Virginia in 1862. More important for Wolseley was the book he published during his second posting, The soldier’s pocket-book for field service (London, 1869). Although he drew on the work of military theoreticians in Canada, such as MacDougall and George Taylor Denison*, this was a pragmatic staff officer’s compendium. Later editions would incorporate aspects of his Canadian experience.

Early in 1870 it became obvious that some form of military expedition would have to be sent to the Red River (Man.) to oversee the transfer of the territory from the Hudson’s Bay Company to Canada and to replace Louis Riel*’s provisional government with a stable authority acceptable in central Canada. Wolseley immediately tried to find some involvement. When he learned that Donald Alexander Smith was to be sent as a special emissary to Riel, he begged his friend George Stephen* to use his influence with Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald* to get him a place accompanying Smith. In fact, he had his eye on the command of any expedition, and his very able memorandum on how it should be conducted made him the only obvious choice. He was, however, “disappointed and disgusted” not to be given a civil mandate as lieutenant governor of Manitoba as well.

The Red River expedition was a fine example of planning in which attention to detail enabled troops carrying all their own supplies to overcome some 600 miles of inhospitable terrain between Lake Superior and the prairies. Although much of the credit for the preparation of the expedition was due to James Alexander Lindsay*, lieutenant-general commanding in British North America, and Sir George-Étienne Cartier*, minister of militia and defence, and his infant department, the execution was Wolseley’s. He moved a force consisting of nearly 400 British troops, over 700 Canadian militia, and a large party of civilian voyageurs and workmen from their port of embarkation at Collingwood, Ont., to the Red River between 3 May and 24 August, without losing a man. Altogether the expedition made 47 portages and ran 51 miles of rapids. On the last stage of the journey to Upper Fort Garry (Winnipeg) Wolseley deployed his little force in tactical formation, but he found the fort empty: Riel and his government had fled. All that remained was for him to welcome Lieutenant Governor Adams George Archibald* on 2 September. He then departed with the British regulars, leaving the militia to maintain order. Later that year he was awarded a kcmg and a cb for his services.

In 1870–71 Wolseley contributed an anonymous article to Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine which was critical of the Canadian government for its mismanagement of affairs at Red River, its surrender (in the Manitoba Act of 1870) to “the French rebel party,” its interference in the preparations for his expedition, and its whole system of political patronage. His pique was possibly the result of the government’s refusal to appoint him lieutenant governor of Manitoba and its repudiation of his proclamation “To the loyal inhabitants of Manitoba,” issued from Prince Arthur’s Landing (Thunder Bay, Ont.).

Wolseley had returned to England in October 1870 to become assistant adjutant-general at the War Office, where he immediately became identified with the reforms initiated by Edward Cardwell, the secretary of state for war. When the possibility of conflict with the Ashanti in West Africa arose, Wolseley wrote to Cardwell outlining a plan of campaign and again became identified as the officer to carry it out. He departed for West Africa in September 1873 with the local rank of major-general and with 35 specially selected officers, a number of them, such as William Francis Butler*, from the Red River expedition. The resulting successful campaign captured the Ashanti capital of Kumasi (Ghana). Wolseley was awarded many honours, obtaining confirmation of his rank as major-general, receiving the thanks of parliament, and being nominated gcmg and kcb.

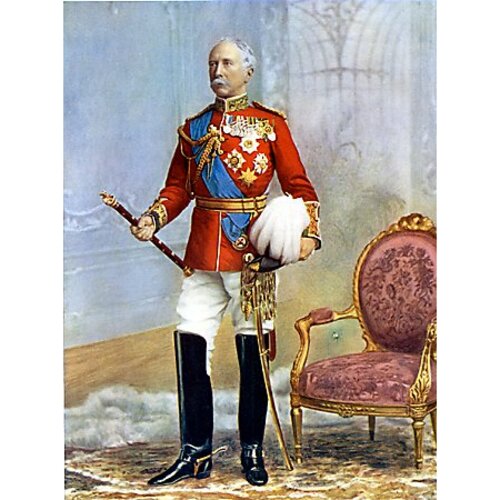

Wolseley subsequently held a number of appointments, as inspector general of the auxiliary forces (1874–75), governor of Natal (1875), a member of the Council of India (1876–78), first administrator of Cyprus (1878–79), and high commissioner to Natal and the Transvaal (1879–80), when he ended the Zulu War by capturing the Zulu king, Cetewayo. On 25 March 1878 he had been promoted lieutenant-general and in 1880 he returned to the War Office, as quartermaster-general. His popularity was then at a peak. He was nominated gcb for his work in southern Africa and was instantly recognizable as “the very model of a modern Major-General” when The pirates of Penzance opened in London that year. In 1882 he was appointed adjutant-general.

In the same year Britain decided to intervene in Egypt following a revolt against Turkish rule. Wolseley was offered the command of nearly 31,000 troops. Not only was this the largest force he had commanded, but it was the first time he had led large numbers of regulars. His night attack at Tell el Kebîr, near Zagazig, on 13 September was decisive in routing his Egyptian opponents and once again he returned home to popular acclaim. He was promoted full general and raised to the peerage as Baron Wolseley of Cairo and Wolseley.

Two years later Britain reluctantly decided to send an expedition under Wolseley to rescue Major-General Charles George Gordon, besieged at Khartoum in the Sudan by the forces of the Mahdī. Wolseley proposed “to send all the dismounted portion of the force up the Nile to Khartum in boats, as we sent the little expeditionary force from Lake Superior to Fort Garry on the Red River in 1870.” At his behest 390 Canadian voyageurs, among them Jean-Baptiste Canadien, were raised to join the expedition. Again the staff included Red River veterans, Butler and Frederick Charles Denison* among them. In December, with his troops moving ponderously up the Nile, the lack of progress obvious to all, Wolseley sent a desert column overland in an attempt to save Gordon, but the plan failed, Khartoum was lost, and the expedition was forced to retreat.

Although Wolseley’s last field command was unsuccessful, he was again thanked by parliament and on 28 Sept. 1885 became a viscount. The remainder of his career was spent as an army administrator. From 1890 to 1894 he commanded the troops in Ireland, being promoted field marshal on 26 May 1894. In 1895 he became commander-in-chief of the army. In spite of declining health he continued to push forward reform and to oversee Britain’s little colonial wars, but southern Africa came to dominate his time in office. He retired at the conclusion of his five-year term in 1900. He had continued to write, publishing, among other works, lives of Marlborough and Napoleon. At the end of 1903 he brought out The story of a soldier’s life, an incomplete autobiography in two volumes which included the Canadian years. In his last years his memory failed and he withdrew from public life.

Lord Wolseley was among the foremost of the Victorian generals. Forced by lack of family wealth to make his own way, he was also driven by ambition to reach the highest levels in his profession. Although he never proved himself as a commander of the first rank, for he never faced a first-class adversary using modern technology and never commanded the bulk of Britain’s army in the field, he was the right commander for success in a wide variety of situations throughout the empire. In addition he became identified with the progressive element in the British army and a spokesman for army reform at a crucial period in that institution’s history.

Wolseley’s time in Canada was an important formative period. His training skills benefited future leaders of the Canadian militia who came under his influence in the camps at La Prairie and Thorold. His talents for organization, planning, and personal leadership brought his expedition safely to Red River and enabled the Canadian government to impose its will on the prairies. For his part, Wolseley took from Canada experience in military innovation, which included the use of troops in unconventional roles and reliance upon a picked body of acquaintances as staff and subordinate commanders, both of which became regular features in his subsequent imperial campaigns.

Material relating to Canada from the Wolseley family papers in the Hove Public Library (Hove, Eng.) is available on microfilm at NA, MG 29, E3.

Wolseley’s anonymously issued “Narrative of the Red River expedition, by an officer of the Expeditionary Force” appears in Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine (Edinburgh and London), 108 (1870): 704–18; 109 (1871): 48–73, 164–81; a monograph version was published under his name in New York around 1871. His account of the Khartoum expedition was issued as In relief of Gordon; Lord Wolseley’s campaign journal of the Khartoum relief expedition, 1884–1885, ed. Adrian Preston (London, 1967), and his two-volume autobiography, The story of a soldier’s life, was published in Westminster (London) in 1903.

NA, RG 9, II, A3, 1–2. Frederick Maurice and George Arthur, The life of Lord Wolseley (Garden City, N.Y., 1924).

Cite This Article

O. A. Cooke, “WOLSELEY, GARNET JOSEPH, 1st Viscount WOLSELEY,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 28, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/wolseley_garnet_joseph_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/wolseley_garnet_joseph_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | O. A. Cooke |

| Title of Article: | WOLSELEY, GARNET JOSEPH, 1st Viscount WOLSELEY |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | February 28, 2026 |