![Portrait d'Idola Saint-Jean. Début des années 1920. Archives de la Ville de Montréal. BM005-2_13. Fonds A.-Léo Leymarie. - [15-]-1981. Original title: Portrait d'Idola Saint-Jean. Début des années 1920. Archives de la Ville de Montréal. BM005-2_13. Fonds A.-Léo Leymarie. - [15-]-1981.](/bioimages/w600.24745.jpg)

Source: Link

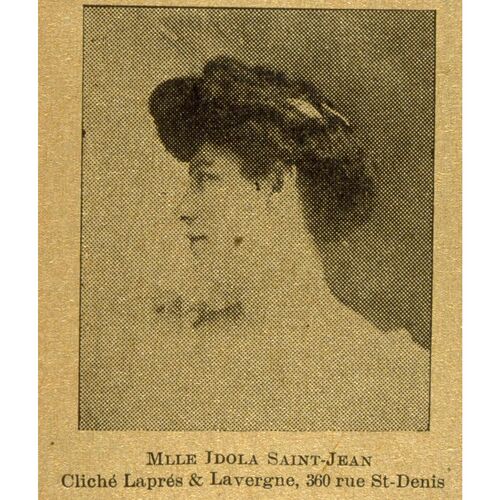

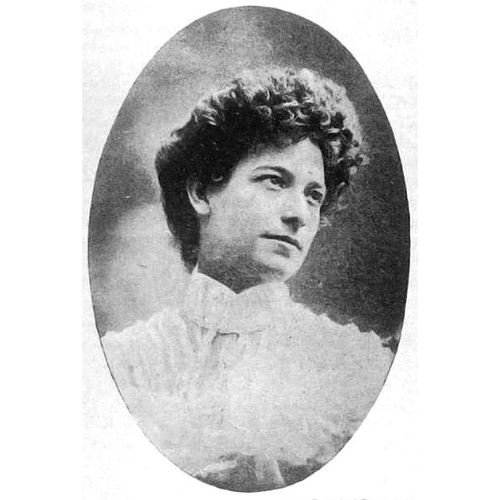

SAINT-JEAN, IDOLA (baptized Marie-Yvonne-Rose-Idola), elocution teacher, actress, militant feminist, author, public speaker, and journalist; b. 19 May 1879 in the parish of Notre-Dame in Montreal, daughter of Edmond-Napoléon Saint-Jean, a law student, and Marie-Élizabeth-Emma Lemoine; d. unmarried 6 April 1945 in Montreal and was buried there three days later in the Notre-Dame-des-Neiges cemetery.

Family and education

An only child, Idola Saint-Jean grew up in Montreal in a well-to-do family. She was educated first by private tutors and then intermittently between 1888 and 1895 in a school that her mother had attended, the Pensionnat Villa-Maria. Run by the nuns of the Congregation of Notre-Dame, it offered a bilingual education. For the next two years she studied at the Académie Saint-Urbain, graduating with a gold medal in 1897. She had, at that point, attained the highest level of schooling then available for girls in a French Catholic environment. In 1887–88 her father, the lawyer Edmond-Napoléon Saint-Jean, had been president of the Club National, a breeding ground for Liberal politicians. In 1888 he joined forces with Liberal politician Raymond Préfontaine* to establish a prominent practice in Montreal; other influential Liberals, such as Lomer Gouin* and Joseph-Emery Robidoux, would later join them. Edmond-Napoléon, an effective speaker, delivered speeches during election campaigns; he did not, however, enter the political arena.

Actress and teacher

The usual path for girls from Idola’s middle-class background was to lead the life of a socialite in preparation for marriage. Instead, when she completed her studies, she took courses in acting and stage direction with Julie Benoît, known as Julia Bennati, a French-born actress living in Montreal. Saint-Jean dreamed of going on stage during a period when Montreal theatre was experiencing something of a golden age. In 1898 the brand-new Monument National, a project of the Association Saint-Jean-Baptiste de Montréal, established a theatre company run by Elzéar Roy and introduced courses in diction, which he immediately entrusted to Saint-Jean. She embarked on a promising acting career, performing chiefly at Karn Hall in Montreal and Tara Hall in Quebec City as well as at the Monument National. On 23 April 1900, however, the sudden death of her father at age 43 placed her and her mother in a difficult financial situation. Soon after, her mother exerted pressure on the religious institutions run by the sisters of the Congregation of Notre-Dame to allow her daughter to teach elocution. In the years that followed, Idola would give instruction in elocution in several schools and convents. She also looked after the affairs of her mother, who lived with her until her death in 1915. In doing so, Idola gained a formidable range of skills, which she put to good use in managing her assets.

Saint-Jean pursued her parallel careers as a teacher and actress until the outbreak of the First World War, taking leading roles in the musical and literary soirées she produced and accepting invitations to recite poems at various events. In 1905 she spent six months studying elocution in Paris with the famous actors Constant Coquelin, known as Coquelin the elder, and Renée-Marie-Louise-Thérèse-Marthe Seveno, known as Renée Du Minil. Before her departure she wrote a letter, dated 5 June, to the archbishop of Montreal, Paul Bruchési*, requesting his support and explaining that she wanted this training in order to “give lessons to the English, which would be much more profitable for [her].” In 1906, having returned to Montreal, she took over the class in French diction at the McGill Conservatorium of Music for at least a year. In 1922 she was hired as a professor of French elocution at McGill University and director of the same discipline at its French summer school, despite the university’s tendency to favour teachers from France for the program. At McGill she rubbed shoulders with anglophone feminists such as botany professor Carrie Matilda Derick. For most of her career she divided her teaching between the two leading linguistic communities, giving courses in French diction at McGill University and at the Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste de Montréal (as the Association Saint-Jean-Baptiste de Montréal was called from 1912) until just a few weeks before her death in 1945.

Guardian of the French language

In 1917 Saint-Jean had published Récitations enfantines, and in 1918 Morceaux à dire. These collections of poetry, released in Montreal, were approved by the Catholic Committee of the Council of Public Instruction in 1928 and distributed to schools; they went through numerous editions. Morceaux à dire included the poem Le vaisseau d’or by Émile Nelligan, whom Saint-Jean knew well: their families were neighbours in Montreal and usually spent summer holidays together at Cacouna. The two young people, who were the same age and cousins by marriage, developed a close relationship; the poet described Idola as his long-time friend and said that he counted her among his dearest comrades. Édouard Montpetit*, an acquaintance from Saint-Jean’s youth, wrote the preface to Morceaux à dire, making an impassioned plea for the French language, which, he declared, was “the expression of our resistance, and [it is] like our living homeland.” In 1901 Saint-Jean had appeared with him at the Monument National in Laurent-Olivier David*’s play Le drapeau de Carillon: drame historique en trois actes et deux tableaux; Camillien Houde* and Louis-Athanase David* were also on the stage. The paths of Saint-Jean and Montpetit would very often cross during the course of their careers.

Committed to promoting and improving the status of French, Saint-Jean toured New England in 1921 to speak about the role of women and the French language. The woman whom Myrto [Anne-Marie Gleason] had dubbed the “guardian of the French language” (in La Revue moderne in 1920) was made a knight of Montreal’s Société du Bon Parler Français in 1929.

Social activist

Outside her exceptional professional life, Saint-Jean became a militant social activist and feminist. She attended the founding convention of the Fédération Nationale Saint-Jean-Baptiste (FNSJB) in 1907. At its 1909 meeting she presented a report of the activities of the Association Artistique des Dames Canadiennes, an organization she had formed the previous year to promote and support women artists; this was her first known social commitment. Through the FNSJB she became acquainted with francophone feminists and thus familiarized herself with social and political activism. In 1915, along with Marie Gérin-Lajoie [Lacoste], Carrie Derick, and others, she protested against the Superior Court of Quebec’s dismissal of the case that would have allowed Annie Langstaf [Macdonald*] to be admitted to the Quebec bar [see Samuel William Jacobs*]. That year, through the Gouttes de Lait associations [see Séverin Lachapelle*] affiliated with the FNSJB, she gave talks on tuberculosis, hygiene, and infant mortality to mothers from Montreal’s working-class districts.

In 1918, during the Spanish flu epidemic, Saint-Jean directed and coordinated a volunteer team from the French section of a relief organization connected with the Uptown Emergency Health Bureau. She took in a child whose parents had succumbed to the virus and cared for her until the girl’s death a few years later.

Around 1914, aware of the plight of juvenile delinquents, Saint-Jean worked with the Children’s Aid Society [see François-Xavier Choquet*]. From 1924 to at least 1925 she was secretary of the new Catholic Children’s Aid Society of Montreal, whose purpose was to assist young people being brought to justice.

In 1919 the journalist Madeleine [Gleason] had founded La Revue moderne, forerunner of the Montreal periodical Châtelaine. Starting in the first issue, Saint-Jean wrote a column on female aesthetics, discussing, among other things, hygiene, health, physical exercise, and a nutritious diet. (She would produce only three pieces on these subjects.) In an article that revealed her values and philosophy of life, she presented to readers the translation of a text by Christian Daa Larson, one of the leaders of the New Thought movement.

In 1923 Saint-Jean began corresponding about psychology and theosophy with Armand Pêche, a widower living in the United States (in the 21st century these letters are held at the Ville de Montréal, Section des archives). Pêche offered marriage, proposing that she join her life with his in “a union more spiritual than carnal.” She refused. The rejected lover, although disappointed, answered that he understood her wish to pursue her life and career in Montreal. He ended his letter with a poem he wrote in which his first two verses referred to the freedom so dear to his beloved: “No circumstance can enslave me, / No power can imprison my soul and my body.”

Speaker and radio presenter

In 1918 Canadian women, except for Indigenous women who were status Indians, won the right to vote in federal elections. They cast their first ballots in the 1921 general election. Acknowledged as an exceptional speaker, Saint-Jean was recruited by the Liberal Party to deliver speeches and encourage women to go to the polls. She met thousands of women, including 600 in Sainte-Agathe-des-Monts and 500 in Terrebonne. It was probably at this time that she developed her passion for politics.

The 1925 federal election campaign that followed allowed Saint-Jean to make her first foray into radio, a new means of communication, when the station CKAC gave her an opportunity to reach out to women voters. In 1928 she broadcast a speech on feminist initiatives in Quebec. Her oratorical skills meant that she regularly took the lead on shows. In 1930 she hosted Les droits des femmes on CFCF, and from 1933 to 1940 L’actualité féminine, first on CHLP and then on CKAC, in which she tackled as many social themes as political ones.

The right to vote in provincial elections

Impressed by women’s accomplishments in various ridings during the 1921 federal campaign, Saint-Jean argued against female exclusion from her province’s political scene. Increasingly aware of this disparity, she resolutely took up the cause of women’s suffrage, which became for her an issue of democracy.

Shortly after the 1921 vote, Saint-Jean worked with Marie Gérin-Lajoie, among others, to set up the Provincial Franchise Committee; their aim was to renew the fight in the provincial arena. Gérin-Lajoie and Anna Marks Lyman jointly presided over the committee, whose founding meeting took place on 14 Jan. 1922. Liberal senator Raoul Dandurand, who was known to support female suffrage, was the only man present. Saint-Jean became the francophone secretary. On 9 February a delegation of some 500 women met with members of Quebec’s Legislative Assembly; the francophone representatives, Idola Saint-Jean, Marie Gérin-Lajoie, and Thérèse Casgrain [Forget*] presented arguments for the right to vote in provincial contests. However, as Le Devoir reported the next day, Liberal premier Louis-Alexandre Taschereau* “dashed the fair hopes of these ladies.”

After this setback the Provincial Franchise Committee lost momentum. For her part Saint-Jean remained active and drew closer to the working class, a development questioned by some members. Intent on having a free hand, she founded the Canadian Alliance for the Women’s Vote in Quebec. Its first meeting was held on 3 Feb. 1927, and until 1940 the new association, which often worked with the League for Women’s Rights headed by Thérèse Casgrain, organized pilgrimages in support of 14 bills on women’s suffrage that were presented to the assembly. In both French and English, the alliance exerted pressure and defended the cause through various means: radio broadcasts, public lectures, and newspaper articles. Most clergymen and politicians shot down each bill. Saint-Jean’s acting talents made her a memorable orator, and her skill in the French language enabled her to continue reaching audiences through the spoken and written word. Album souvenir 1931, published that year by the Canadian Alliance for the Women’s Vote in Québec, became La Sphère féminine (Westmount), an annual bilingual review, two years later. With its distinctive title, the periodical was essentially intended to show that the world of women extended far beyond hearth and home to encompass every aspect of social life. The final issue, written mostly by Saint-Jean, appeared the year after her death.

The persons case and the Dorion commission

Soon after winning the right to vote in federal elections, women’s associations from all over Canada mobilized for women to be admitted to the Senate. According to section 24 of the British North America Act, only “qualified persons” could sit in the Upper Chamber. The legal interpretation of the term “persons” included only men. On 24 April 1928 a petition presented by five Albertan women – Henrietta Louise Edwards [Muir*], Mary Irene Parlby [Marryat*], Helen Letitia McClung [Mooney*], Louise McKinney [Crummy*], and Emily Gowan Murphy [Ferguson*] – was rejected by the Supreme Court of Canada, which declared that women were not “qualified persons” [see Francis Alexander Anglin*]. The five appealed to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. Saint-Jean then conducted a campaign for Quebec’s provincial government to withdraw its objections to their appeal. The following year, on 18 October, the council quashed the Supreme Court’s decision. Because of Saint-Jean’s important work for the cause, some voices, including those of Liberal women, called for her to be appointed to the Senate. To her great disappointment, in February 1930 the government chose instead Ontario resident Cairine Reay Wilson [Mackay*] as the first female senator of Canada.

According to the Civil Code of Lower Canada, unmarried women such as Idola Saint-Jean had the same rights as men. But the legal status of married women was equivalent to that of minors or persons considered incapable because of mental illness. Having dealt with her father’s estate, Saint-Jean was aware from a young age of the importance of the law in daily life, and she backed the demands of Marie Gérin-Lajoie, who had been fighting since the beginning of the century for reform of the Civil Code. Finally, in 1929 the provincial government created the Commission des Droits Civils de la Femme, chaired by the judge Charles-Édouard Dorion [see Joseph Sirois]. Saint-Jean submitted a brief, requesting among other things that the legal age for marriage – at the time 14 for boys and 12 for girls – be raised to 16. The commissioners recommended that the law be changed to make 16 the legal age for boys and 14 for girls. However, they denied Saint-Jean’s request to abolish the double standard regarding adultery: a woman could request a legal separation only if her husband brought his mistress to live in the family home, whereas a man had only to claim that his wife had committed adultery to obtain a separation.

Shortly before the Dorion commission’s first hearing on 4 Nov. 1929, the Montreal Herald launched a vigorous campaign against the inferior legal status of married women in Quebec and appointed Saint-Jean as editorial writer. Each day she produced a bilingual page of feminist news and an editorial. While the commission’s sessions were taking place in Montreal, the daily published a series of caricatures on the legal status of Quebec women, entitled “Are women people?” They were accompanied by Saint-Jean’s bilingual editorials on each of the demands being made by women. The series was so successful that the Herald issued the caricatures in a bilingual brochure. Her comments in the press contrasted strongly with those made in measured tones by Marie Gérin-Lajoie and Thérèse Casgrain, who also appeared before the Dorion commission. Her work stirred up enormous controversy. Some newspapers, such as Le Soleil, saw her material as a coordinated insult by anglophone circles against French Canadian traditions. Despite the unprecedented mobilization of feminist organizations, the legal status of married women made only minimal advances in the years that followed; in 1931 married women gained the right to retain their salaries, and women who had separated from their husbands won the rights held by widows and unmarried women.

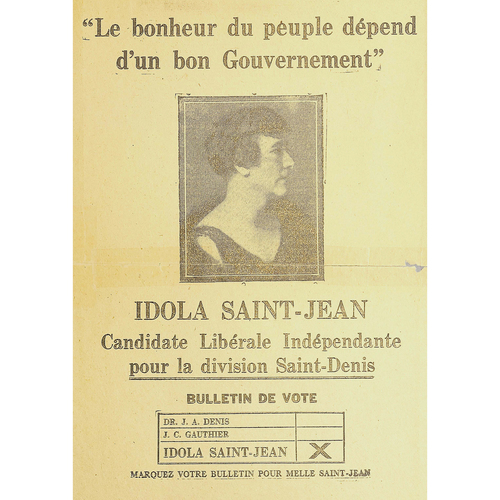

First French Canadian woman candidate in a federal election

At the request of a group of Liberal women voters, the indefatigable Saint-Jean agreed to stand as an independent Liberal candidate in the Montreal riding of Saint-Denis in the 1930 federal election. Her decision displeased the Liberal Party establishment, which backed only one female candidate, Dr Octavia Grace England [Ritchie], an early supporter of women’s suffrage and president of the Montreal Women’s Liberal Club, who ran in the riding of Mount Royal. Saint-Jean distributed a decidedly feminist election flyer. Even though she knew she would not win the seat, she wanted to take advantage of the campaign to publicize women’s demands. The first French Canadian woman to enter a federal contest, she gained 1,732 votes (4 per cent of the ballot) on 28 July. This episode marked her decisive break with both the Liberal Party and women’s political associations. Her wish to retain her independence regarding certain matters, particularly women’s issues, was evident. Her stint at the Montreal Herald as an editorial writer ended shortly thereafter, on 19 August.

The dream of a just society

In a letter reprinted in the 1938–39 edition of La Sphère féminine, Saint-Jean defended “political emancipation … based on logic and justice. The women of Quebec have the same obligations as men and enjoy no rights whatsoever.” In a key text published on 28 Jan. 1928 in Montreal’s Monde ouvrier, she had laid out the conceptual foundation of her vision of democracy and feminism: “Man[,] having done away with the privileges of rank, caste and birth, will abolish the last remaining aristocracy, the aristocracy of the sexes.… As soon as the government is no longer the prerogative of a few privileged people, and on the day [that] the general will has replaced the monarch’s will, [and] democracy [has] been born,… logic dictates that the sovereignty of all belongs to all.” In her opinion men and women, coming from the same society, must work together. This approach viewed men not as enemies but as allies. For her, liberalism, in the full sense of the word, included female emancipation. Having this sense of justice, in 1935 she strongly opposed the bill introduced by the Liberal mla Joseph-Achille Francœur, which sought to prevent women from working, unless they were obliged to provide for their own needs or the needs of their families, on the grounds that they would take jobs that would otherwise go to men. Premier Taschereau and a majority of mlas rejected the bill.

The stock-market crash of 1929 had plunged Canada into an unprecedented economic slump. In 1933, 30 per cent of the workforce in Quebec was unemployed. Religious and private charity were no longer enough. To explore new models, various government commissions looked into social and economic problems. Saint-Jean was very much aware of the situation of people in need, especially poor women, and made sure that their voices were heard. In 1931 she presented a brief to the Quebec Social Insurance Commission, also known as the Montpetit commission [see Édouard Montpetit], asking for an allowance for mothers in need, health insurance for all employees earning less than $2,000 a year, a pension for the elderly, and protection for adopted and illegitimate children.

In July 1933 the federal government created the royal commission on banking and currency in Canada, chaired by Lord Macmillan. Its principal mandate was to consider the workings of financial law and the value of establishing a central bank in the country. Saint-Jean submitted a brief proposing that women be able to deposit more than $2,000 in a bank account without their husband’s consent. Victory was achieved: in 1934, partly because of her efforts, the Bank Act allowed financial institutions to accept deposits from all individuals regardless of age or their marital or social status.

Finally, in 1938 Saint-Jean acted on behalf of caregivers by appealing to the Rowell–Sirois commission [see Newton Wesley Rowell; Joseph Sirois], which examined the relations between the dominion and the provinces. She asked that those taking care of individuals for whom they were the sole support receive a tax exemption of $2,000 or more, as did taxpayers who contributed cash to a charitable organization.

Rights and pacifism

Widening the scope of her activities, in the 1930s Saint-Jean became a member of the executive of Equal Rights International, based in Geneva. She fully supported its demands, which included, among other things, that a married woman was free to choose whether to retain her own nationality or adopt that of her spouse.

The deteriorating situation in Europe, which augured another armed conflict, inspired a pacifist movement that Saint-Jean joined in 1935: she agreed to take charge of the Committee for Peace of the Montreal chapter of the Royal Empire Society. In 1938 she also became involved in the Canadian Civil Liberties Union. Her strong commitment to peace led historian Robert Rumilly* to remark that she was “as much a pacifist as a feminist.”

Winning the right to vote and last years

Following the 1939 defeat of Maurice Le Noblet Duplessis*’s Union Nationale and the ascent to power of Adélard Godbout*’s Liberal Party, women (except for Indigenous women) finally won the right to vote in provincial elections with the passing on 25 April 1940 of the Act granting to women the right to vote and to be eligible as candidates [see The right to vote in provincial and territorial elections]. It was not long before Saint-Jean announced (11 May) that the Canadian Alliance for the Women’s Vote in Québec would become the Alliance Canadienne des Électrices du Québec. Declaring itself independent of all political parties, the organization adopted the goal of obtaining for Quebec women rights equal to those of men.

In 1944 Saint-Jean voted in a provincial election for the first time. In a radio broadcast, she invited women to vote but endorsed no party. There remain few traces of her personal life during this period, but her will reveals that she had a special bond with Angelo Amighetti, an Italian Canadian who, according to sources, was a sales agent or importer and had been imprisoned in Petawawa, Ont., at the beginning of the Second World War. In her will she not only named him executor, but also made him her principal beneficiary. Her bequest to him consisted chiefly of three residences acquired between 1926 and 1939. Following a short illness, she died on 6 April 1945, aged 65. At her funeral nine women, friends who had fought alongside her, carried her coffin.

Tributes and legacy

The newspapers published many posthumous testimonials honouring Saint-Jean, emphasizing in particular her exceptional courage in the fight for women’s suffrage. La Société du Bon Parler Français made a point of recalling her love of the French language.

In 1998 the Canadian government recognized Idola Saint-Jean as a person of national historic significance, and in 2019 the Quebec government designated her a historic figure. A statuary group, Monument en homage aux femmes en politique, honouring women active in political struggle, was created by Jules Lasalle and erected in 2012 near the legislative building in Quebec City. It placed Idola Saint-Jean with Marie Gérin-Lajoie, Thérèse Casgrain, and Marie-Claire Strover [Kirkland*], linking these four pioneers of women’s rights.

Idola Saint-Jean made her mark at a time when Quebec feminists were navigating a cautious course, taking care not to antagonize political and religious elites while moving towards a strong western current that sought to modernize women’s economic, political, and legal status. Modern, clear-sighted, and sophisticated, she understood that the world was changing and the future of women would depend on the acquisition of their rights. Single and self-employed, she irritated several religious and political leaders, but she also won the admiration of society’s most vulnerable members. No decree imposed by clergymen or political leaders made her give way. Her thinking was broadly feminist and inclusive, and her actions resonated with both anglophones and francophones. She helped free women’s voices, stating in the 1936–37 edition of La Sphère féminine that feminists’ watchword should be “[the] free woman in a free world.” Regarding equality, she continued: “Let us not confuse equality with identity. Winning her freedom will not make a woman the same as a man – this in any case is not her aim – but it will allow her to liberate herself, develop her social conscience, and express herself freely.” Saint-Jean’s nationalism was not rooted in a view of the traditional role of women, which made them responsible for the survival of the French fact in North America by becoming mothers, but in the granting of rights that would allow them to be full and equal citizens in a modern democracy that was open to the world. Idola Saint-Jean firmly believed that women should be involved in the public sphere, not because they were mothers, but because they were members of the human race. She thereby contributed to defining the feminism that would leave its mark on Quebec from the 1960s onward.

Idola Saint-Jean is also the author of Récitations pour les élèves du cours supérieur de diction française (Montréal, 1917).

Arch. de la Chancellerie de l’Archevêché de Montréal, 901.173.2.11; 905-1 (fonds Paul Bruchési [lettre d’Idola Saint-Jean rédigée le 5 juin 1905]). Arch. de la Congrégation de Notre-Dame (Montréal), AL266 (fonds Académie Saint-Léon (Montréal, Québec)); AL459 (fonds École Saint-Urbain (Montréal, Québec)); AL480 (fonds Collège Villa Maria (Montréal, Québec)); R0046 (fonds Pulchérie Cormier (S.S.-Anaclet)). Bibliothèque et Arch. Nationales du Québec, Centre d’arch. de Montréal, CE601-S51, 20 mai 1879. Ville de Montréal, Section des arch., BM102.

Le Devoir (Montréal), 1910–45. Montreal Herald, 1929–30. La Patrie (Montréal), 1889, 1909–45. Le Soleil (Québec), 13 déc. 1929. Denyse Baillargeon, Brève histoire des femmes au Québec ([Montréal], 2012). C. L. Cleverdon, The woman suffrage movement in Canada, intro. Ramsay Cook (2nd ed., Toronto, 1974). Maryse Darsigny, L’épopée du suffrage féminin au Québec, 1920–1940 ([Montréal], 1990). Directory, Montreal. Micheline Dumont et al. (le Collectif Clio), L’Histoire des femmes au Québec depuis quatre siècles (éd. rév., Montréal, 1992). Magda Fahrni, “‘Elles sont partout …’: les femmes et la ville en temps d’épidémie, Montréal, 1918–1920,” Rev. d’hist. de l’Amérique française (Montréal), 58 (2004–5): 67–85. Nicolle Forget, Thérèse Casgrain: la gauchiste en collier de perles ([Montréal], 2013). Gilles Gallichan, “Idola Saint-Jean: femme de cœur et femme de tête,” Bibliothèque de l’Assemblée Nationale, Bull. (Québec), 39 (2010), no.1: 16–23. Madeleine [A.-M.] Gleason-Huguenin, Portraits de femmes ([Montréal], 1938). Diane Lamoureux, “Idola Saint-Jean: l’amazone du suffrage,” in Citoyennes?: femmes, droit de vote et démocratie (Montréal, 1989), 67–88; “Idola Saint-Jean et le radicalisme féministe de l’entre-deux-guerres,” Recherches féministes (Québec), 4 (1991), no.2: 45–60. J.-M. Larrue, Le théâtre à Montréal à la fin du xixe siècle (Montréal, 1981). Marie Lavigne, “18 avril 1940, l’adoption du droit de vote des femmes: le résultat d’un long combat,” in Dix journées qui ont fait le Québec, sous la dir. de Pierre Graveline et Myriam D’Arcy (Montréal, 2013), 161–85. Marie Lavigne et Michèle Stanton-Jean, Idola Saint-Jean, l’insoumise: biographie ([Montréal], 2017). Andrée Lévesque, Éva Circé-Côté: libre-penseuse, 1871–1949 (Montréal, 2010). Michel Lévesque, Histoire du Parti libéral du Québec: la nébuleuse politique, 1867–1960 (Québec, [2013]). P.-A. Linteau, Histoire de Montréal depuis la confédération (2e éd., Montréal, 2000). Montreal Herald, The “Montreal Herald” presents: are women people? A stirring real life drama in twelve scenes ([Montreal, 1930]). Myrto [A.-M. Gleason], “Une gardienne de la langue française: mademoiselle Idola Saint-Jean,” La Rev. moderne (Montréal), 2 (1920–21), no.1: 25. National reference book on Canadian men and women with other general information for library, newspaper, educational and individual use (6th ed., n.p., 1940), 625. Hélène Pelletier-Baillargeon, Marie Gérin-Lajoie: de mère en fille, la cause des femmes (Montréal, 1985). Robert Rumilly, Chefs de file (Montréal, 1934). Sœur Sainte-Henriette [Marie-Darie-Aurélie Lemire-Marsolais], Histoire de la Congrégation de Notre-Dame de Montréal (11 tomes en 13v., Montréal, 1941–74), v.10, tome 1 (1855–1900) [the author of v.10–11 is Thérèse Lambert, dite sœur Sainte-Marie-Médiatrice]. Michèle [Stanton-]Jean, “Idola Saint-Jean, féministe (1880–1945),” in Mon héroïne: les lundis de l’histoire des femmes, an 1, conférences du théâtre expérimental des femmes, Montréal, 1980–81 (Montréal, 1981), 117–47; Québecoises du 20e siècle (Montréal, 1974). Travailleuses et féministes: les femmes dans la société québécoise, sous la dir. de Marie Lavigne et Yolande Pinard (Montréal, 1983).

Cite This Article

Marie Lavigne and Michèle Stanton-Jean, “SAINT-JEAN, IDOLA (baptized Marie-Yvonne-Rose-Idola),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 17, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 8, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/saint_jean_idola_17E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/saint_jean_idola_17E.html |

| Author of Article: | Marie Lavigne and Michèle Stanton-Jean |

| Title of Article: | SAINT-JEAN, IDOLA (baptized Marie-Yvonne-Rose-Idola) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 17 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2025 |

| Year of revision: | 2025 |

| Access Date: | February 8, 2026 |