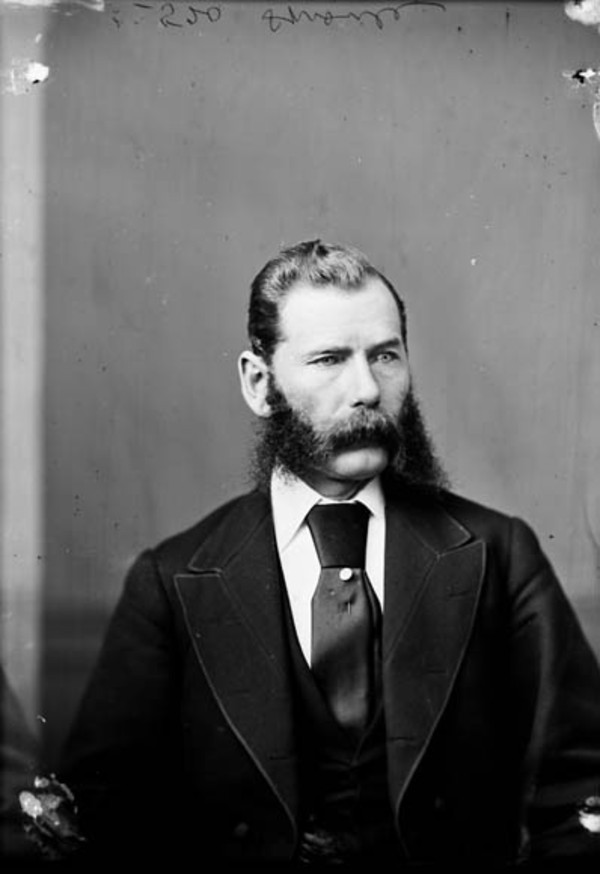

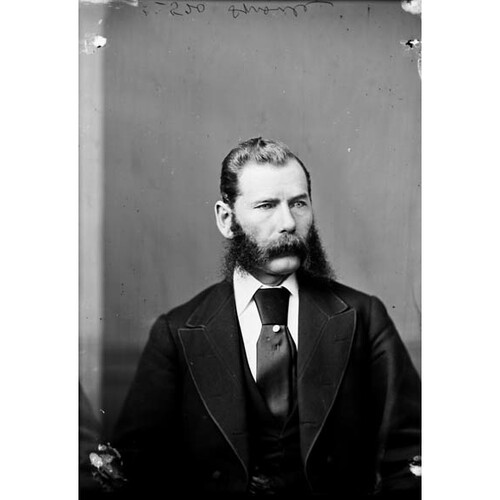

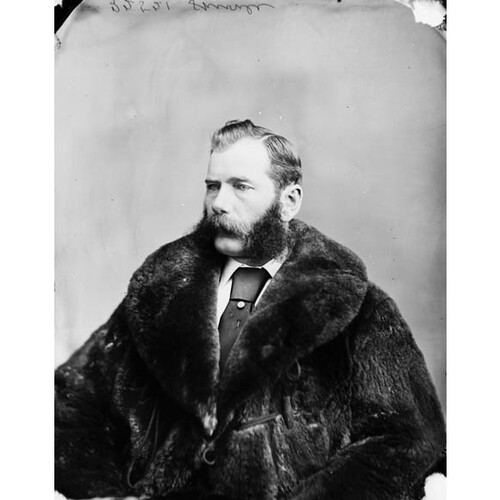

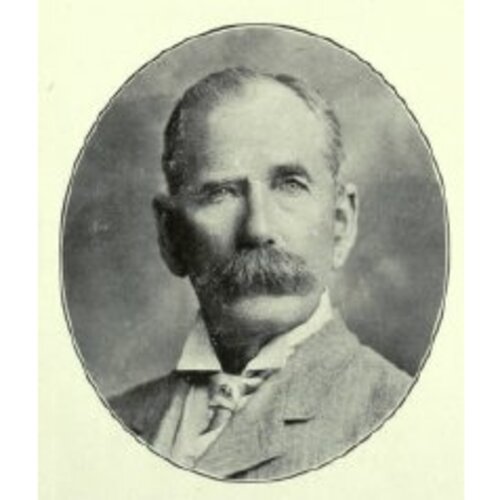

SPROULE, THOMAS SIMPSON, physician, politician, and Orangeman; b. 25 Oct. 1843 in King Township, Upper Canada, son of James Sproule and Jane Mitchell, farmers; m. 7 Sept. 1881 Mary Alice Flesher in Flesherton, Ont., and they had a daughter; d. 10 Nov. 1917 in Markdale, Ont.

Thomas Sproule’s parents, natives of County Tyrone (Northern Ireland), immigrated to Upper Canada in 1836; about 1852 the family settled in Osprey Township in Grey County. After attending public school, Thomas enrolled at the University of Michigan. He then worked in commercial life for two years before taking up medical studies in Cobourg, Upper Canada, at Victoria College, from which he received his md in 1868. The following year, after short periods of practice in Craighurst, Ont., and Galesburg, Mich., he set up in Grey in the village of Markdale; until 1880 he also operated a drug and stationery store. Some two years later he took up farming as well and started raising horses and Shorthorn cattle. A member of Glenelg Township Council in 1877 and a staunch Conservative, in the federal election of 1878 he had won Grey East, which he would represent until 1915.

Sproule became a familiar figure in his riding as a physician, politician, and energetic supporter of the local agricultural society, but it was his association with the Orange order that was eventually to propel him into the national spotlight. He had joined the order in 1862 and his vigorous advocacy of the Orange viewpoint made him a well-known figure on Parliament Hill. The Jesuits’ Estates Act of 1888 in Quebec, which authorized the pope to adjudicate compensation for the Jesuit lands held in escheat, outraged Orangemen, who believed the Quebec government had conferred special privileges upon the Roman Catholic Church. In March 1889 a number of Conservative mps, including Orange grand master Nathaniel Clarke Wallace*, broke party ranks to support a motion to disallow the act. Sproule refused to become involved and he stood with his party to defeat the motion. In the election of 1891 his constituents voiced their displeasure by reducing his margin to 19 votes.

Future religious controversies were to offer Sproule the opportunity to rehabilitate his standing among Orangemen and other militant Protestants. The Conservative government’s decision in March 1895 to issue a remedial order requiring the government of Manitoba to restore provincially supported Catholic schools, which had been abolished in 1890, badly divided the party’s caucus [see Sir Mackenzie Bowell]. Sproule was approached about a cabinet position provided that he support the bill giving legislative force to the government’s remedial order. Confronted once again with the choice of backing his party or acting on Orange principles, he rejected the approach. At a major protest meeting in Toronto in February 1896, he registered his opposition to the bill as one of the chief speakers, along with Wallace, D’Alton McCarthy*, and other luminaries in the anti-remedial movement. When the bill came to second reading in March, Sproule and 17 other Conservatives bolted to vote against the government. The disaffected Conservatives and anti-remedial Liberals started to filibuster final reading on 1 April and Sproule took his turn with others to speak six to eight hours at a time, forcing the government to withdraw the bill and call an election for June. Sproule campaigned on an anti-remedialist platform, as did almost half the Conservative candidates in Ontario, and he took his seat with a comfortable majority.

Although the Conservatives went down to defeat overall, Sproule’s star was on the rise. By 1901 he had become deputy grand master of the Orange Grand Lodge. When Wallace died unexpectedly in October 1901, Sproule became acting grand master; the following year the Grand Lodge confirmed him in this office, which he would occupy till 1911. From the opposition benches in the House of Commons, Sproule regularly excoriated the Liberal government of Sir Wilfrid Laurier on issues popular with the Orange order. Foremost was devotion to the British empire. At almost every turn Sproule saw signs of the Liberals’ infidelity, notably their decision to send only volunteers to the South African War, their rejection of Joseph Chamberlain’s scheme for imperial defence under British control, and their refusal to negotiate a preferential trade agreement with Britain. Sproule’s belief that the government was insufficiently committed to the nation’s British identity led him to denounce the Liberal policy of recruiting immigrants from continental Europe: it opened the country to all sorts of “riff raff” and thus endangered the dominion’s British character.

Of all the legislation proposed by the Liberals, the Autonomy Bills of 1905, which created the provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan, alarmed Orangemen the most. The bills proposed to restore a separate school system in each province. In response, Sproule orchestrated among Orange lodges a nationwide petition campaign to protest the legislation and demand that the new provinces be given a free hand in educational matters. In the event, dissent within cabinet forced the government to embrace the status quo, which allowed minorities to establish their own schools and reserved religious instruction to after-school hours. This decision did not, however, end the controversy. When newspapers revealed that the Holy See’s delegate to Canada, Donato Sbarretti y Tazza, had sought concessions for Catholic education in Manitoba, Sproule’s campaign gained momentum. Such papal action, Orangemen believed, was a flagrant instance of interference in Canada’s internal affairs, and Sproule was quick to insist in 1905 that only by eliminating all state support for Catholic education could the country rid itself of this incubus.

Sproule’s efforts in the commons won him a special commendation at the meeting of the Orange order’s Grand Lodge in 1905, in which year he also became a director of the order’s influential organ, the Sentinel and Orange and Protestant Advocate (Toronto). Another indication of his growing stature occurred in 1906, when he became president of the Triennial Grand Orange Council of the World for a three-year term. His attacks on Catholicism during this period captured the venomous ethos of Orangeism. At the order’s annual meeting in Vancouver in June 1907, Sproule’s twisted interpretation of an alleged visit to Rome by Laurier and William Stevens Fielding* as more evidence of papal interference fell on receptive ears, as did open criticism of Conservative party leader Robert Laird Borden* for his failure to pledge to restore control of education to the new western provinces. Three years later Sproule contributed as well to the pressure being brought to bear on the Conservative government of Sir James Pliny Whitney in Ontario for the abolition of bilingual schools. “Down in the Province of Quebec,” Sproule proclaimed in typically paranoid rhetoric, “desolation and ignorance were rampant owing to the action of the Roman Church. The Church was not content with its work in Quebec, but was invading the great Protestant Province of Ontario.”

Although Sproule’s championing of causes dear to Orangemen won him plaudits in the commons and out, his intemperance undoubtedly complicated Borden’s attempts to revitalize the Conservative party, which remained conscious of its Orange support. Within the order, Sproule’s plans to eliminate rituals distinctive to its Canadian branch proved to be extremely unpopular; in the summer of 1911 he resigned as grand master and was replaced by James Henderson Scott of Walkerton, Ont.

That September the Conservatives swept into power and on 15 November Sproule was selected as speaker of the commons, a move that was greeted with enthusiasm by Orangemen, as the government no doubt expected. Sproule’s mastery of procedure and precedent was well recognized, but as a vigorous and outspoken partisan, he was temperamentally unsuited to a post that required tact and skill in managing an often unruly house. He was severely tested in the spring of 1913 when, during the highly charged debate over funding for the British navy, tempers flared amid Liberal denunciations of closure. Because the proceedings got out of hand under the committee chairman, Sproule retook the speaker’s chair but, soon flustered by the rowdy floor, he too lost control of the debate. After threatening the expulsion of an mp, a “trembling” speaker left it to Borden and others to find a way to retreat and wind up the late-hour debate, which the press headlined as “the most remarkable parliamentary battle in Canadian history.” Declining health forced Sproule to decide not to contest the next general election, which was deferred in 1915 because of wartime, and on 3 Dec. 1915 Borden appointed him, at age 72, to the Senate.

In May 1917 Sproule underwent surgery for intestinal pain, an operation from which he never fully recovered. The following November he died at his home; he left his properties in Markdale, including a drugstore, and his farm lots to his wife and daughter, Lillian Clarice Turner. The crowd attending his funeral in Markdale overflowed the local Methodist church, of which he had been a member, and he was buried according to Orange ritual. Soon after his death a local lodge was named in his memory, but in the pantheon of departed Orange heroes, Sproule was to remain in the shadow of Clarke Wallace, his predecessor as grand master. Nevertheless, under Sproule’s stewardship the order had thrived, particularly in the west, where it experienced rapid growth as a result of its opposition to Catholic schooling.

AO, RG 22-356, no.1452; RG 80-5-0-106, no.3420. NA, MG 26, H; MG 29, D61: 7671; RG 31, C1, 1901, Markdale, Ont.: 3 (mfm. at AO). Daily Mail and Empire (Toronto), 24 Feb. 1896, 17 March 1913. Evening Telegram (Toronto), 4 April 1896. Globe, 17 March 1913, 12 Nov. 1917. Markdale Standard, 1 Oct., 10 Dec. 1880; 15 Nov. 1917. Sentinel and Orange and Protestant Advocate (Toronto), 1888–1918. Toronto Daily Star, 17 March 1913. World (Toronto), 8 March 1896. Can., House of Commons, Debates, 1878–1915; Senate, Debates, 1916–17. Canadian annual rev. (Hopkins), 1905–7. CPG, 1915. Encyclopaedia of Canadian biography . . . (3v., Montreal and Toronto, 1904–7), 3: 91. Gary Levy, Speakers of the House of Commons (Ottawa, 1991). E. L. Marsh, A history of the county of Grey (Owen Sound, Ont., 1931). F. A. Walker, Catholic education and politics in Ontario . . . (3v., Toronto, 1955–87; vols.1–2 repr. 1976), 2: 254.

Cite This Article

Brian P. Clarke, “SPROULE, THOMAS SIMPSON,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 19, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/sproule_thomas_simpson_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/sproule_thomas_simpson_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Brian P. Clarke |

| Title of Article: | SPROULE, THOMAS SIMPSON |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | February 19, 2026 |