Source: Link

TRAVERS, MARY (baptized Marie-Rose-Anne, called Madame Édouard Bolduc, Madame Ed. Bolduc, or Madame Bolduc on the playbills of her shows), known as La Bolduc (Bolduc), musician, self-taught singer-songwriter, and actor; b. 4 June 1894 in Newport (Chandler), Que., third child of Lawrence Travers, a day labourer, and his second wife, Adéline Cyr; m. 17 Aug. 1914 Édouard Bolduc in the parish of Sacré-Cœur-de-Jésus, Montreal, and they had seven children, four of whom reached adulthood; d. 20 Feb. 1941 in Montreal and was buried there four days later in Notre-Dame-des-Neiges cemetery.

Childhood in the Gaspé peninsula

Mary Travers grew up in the Gaspé peninsula in a large, impoverished family; she had five siblings from her father’s first marriage and five from the second. Born to an anglophone father of Irish ancestry and a French Canadian mother from Acadia, she was brought up in English but went to a French school. However, she attended classes only up to the time of her first communion. Letters and postcards she later wrote to family and friends, and the few manuscripts of her song lyrics, testify to her low level of education. A self-taught musician, she was encouraged by her father to play the violin, and she also mastered the accordion, harmonica, and jew’s harp.

Montreal: early employment and marriage

In 1907 Mary, aged 13, joined her half-sister Maryann in Montreal to find work. She was initially a maid – an experience that would become the subject of her song La servante – and then worked in a textile factory and was self-employed as a seamstress, as indicated by a contract dated 22 March 1913 for rental of a Singer sewing machine at $2 a month. A practising Roman Catholic, she took part in the social life of her parish, Sacré-Cœur-de-Jésus, which organized activities. It was perhaps there that she met Edmond Bolduc, who introduced her to his brother Édouard, a labourer at the Dominion Rubber Company Limited. She and Édouard were married in 1914.

After her marriage, Bolduc continued to work until her first pregnancy. Subsequently, Édouard’s salary alone became barely sufficient, and the family’s standard of living deteriorated with each new birth. Two of the couple’s children died for lack of proper hygiene and money for medical attention. Hoping for better days, the Bolducs, like many other French Canadians who tried to improve their lot in the United States, travelled to Springfield, Mass., in 1921. Édouard could not find steady employment, however, and they returned to Montreal the following spring. He went back to work at the Dominion Rubber Company Limited and made ends meet with plumbing contracts.

Shows, recordings, and tours

Social life resumed in the Bolduc household, where there was often music making with friends for entertainment. Mary’s musical talent was noticed by, among others, the fiddler and jig-dancer Gustave Doiron. In 1928 Édouard had to stop working following a visit to the dentist that went wrong – the dentist extracted all of his patient’s teeth without his consent. Édouard also suffered from nervous dyspepsia. It was in these circumstances that, about a year before the stock market collapse of October 1929, Mary Bolduc launched a career as a professional performer with the help of Doiron. He spoke highly of her talents to Conrad Gauthier, who since 1921 had organized the show Veillées du bon vieux temps at the Monument National several times a year (at Mardi Gras or Christmas, for example). Bolduc was initially an orchestral musician in the productions but then became a singer. The evenings were very popular, featuring skits, dances, songs, and plays. In November 1928, after the soirée celebrating St Catherine’s Day, Bolduc also took part in a CKAC radio broadcast. In a 7 December article in Montreal’s La Presse, a photo of her alone accompanied an announcement about Gauthier’s Christmas show, which indicates that the public already knew and appreciated her.

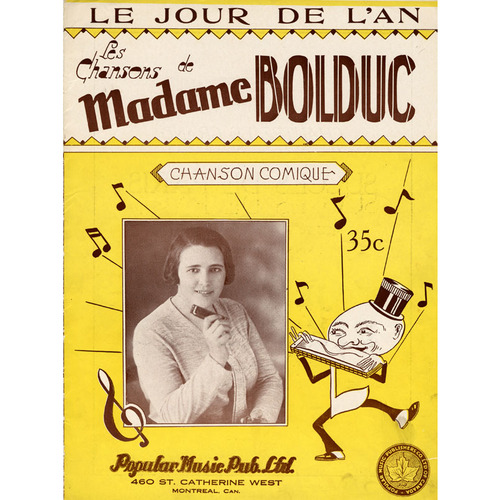

In 1929 Mary Bolduc made her earliest recordings, first as the accompanist to popular artists such as Eugène Daignault, Ovila Légaré, and Alfred Montmarquette, and then as a performer under contract to Roméo Beaudry, artistic director of the Starr Company. On 12 April she recorded Y’a longtemps que je couche par terre, an old song that had originated in France, and La Gaspésienne, a reel. However, true success came only with her first composition, La cuisinière, a comic song recorded during her fourth session at the Starr studio on 6 December. This record sold over 10,000 copies and earned her $400 in royalties in addition to $50 for recording the song. It marked the beginning of a career that lasted a little more than ten years and turned her life and marriage upside down. She had become the first leading star of the French Canadian chanson. Her income supported the family in relative comfort, whereas Édouard had trouble finding work and earned a lower wage.

Bolduc recorded eight songs in 1929 and another 30 the following year, all while continuing to accompany Daignault, Légaré, and Montmarquette in the studio and participate in radio broadcasts. In October 1930 she made her acting debut at the Monument National in the play Feu follet … by Auguste-Henri de Trémaudan*; in November she was in Lachute to perform her repertoire during her first solo stage appearance. The Starr recording company’s advertisement in Montreal’s La Patrie on 15 November introduced her as “the most popular comic singer in all Quebec.”

In 1931 Mary Bolduc recorded 20 songs, including two played with her family for the festive season. Her fame spread beyond Montreal and the surrounding area. She appeared from 15 to 21 March at Quebec City’s Théâtre Arlequin, where the burlesque company of Juliette d’Argère, known as Caroline, was performing. Afterwards she travelled with that company to Hull (Gatineau) and undertook her first tour on 24 May. She went on to Ottawa and various locations in the Outaouais area before going to the Côte-Nord region. On her return to Montreal, she acquired the legal status of marchande publique, a woman who could transact business in her own right. This change allowed her a certain amount of financial independence, and she opened an account in her own name at the Banque Canadienne Nationale.

Troupe du Bon Vieux Temps

In 1932 Mary Bolduc recorded only 12 songs. The Great Depression, as well as competition from radio and talking films, ushered in a difficult era for the recording industry. As well, Beaudry died suddenly in March, and his successor at the Starr company stopped making records. Between 2 July 1932 and 6 March 1935, Bolduc recorded no new songs. Her stage career nevertheless continued when she formed the Troupe du Bon Vieux Temps, the management of which she at times entrusted to Jean Grimaldi* and at others to Willie Plante, known as Henri Rollin. Working with her company, whose shows combined vaudeville and folk music modelled on Gauthier’s Veillées du bon vieux temps, she also took on the starring role for a singing tour. She went on several tours between 1932 and 1940, travelling as far as Abitibi, Kapuskasing in northern Ontario, and New England. She often performed in parish halls, arenas, and cinema theatres, where her show would include a film. She also took advantage of the intermissions to sell booklets with the lyrics of her songs. Between tours and engagements in various theatres in Montreal and its surroundings, she returned to the studio, recording two songs in 1935 and eight in 1936. Her daughter Denise, who had accompanied her on the road since 1932, became her studio pianist. In February 1937 Bolduc sang for the first time in a Montreal cabaret, the American Grill.

Accident

On 9 June 1937 Bolduc’s company started a tour in Trois-Rivières, which would have taken it as far as the Gaspé peninsula. But on the 25th the car in which they were travelling, a 1931 Dodge driven by Rollin, collided with another vehicle in Notre-Dame-du-Sacré-Cœur (Rimouski). It was a serious accident: Mary Bolduc sustained numerous injuries, including fractures of her right leg, pelvis, vertebrae, backbone, and nose; she also suffered brain damage. Her convalescence would be lengthy, especially since, during their examinations, doctors found cancer. She had two operations in January 1938, followed by radium treatments at Montreal’s Institut du Radium between 18 and 30 March, and radiation therapy between 17 March and 30 June.

During this period, Mary Bolduc filed a lawsuit against the drivers involved in the accident, Rollin and Joseph-Louis Bilodeau, a commercial traveller. The proceedings, which lasted from 8 Sept. 1937 to 20 Sept. 1939, were quite an ordeal for her. Although she asked for $7,000 in damages, she received only $250 in compensation. Édouard, who had taken out the insurance policy, received $700 for his wife’s injuries, $230 for medical expenses, and $310 for his car and trailer.

Despite everything, even though she suffered a damaged memory and aphasia, she tried to stage a comeback in the summer of 1938. A period of remission allowed her to resume her activities in 1939. On 11 January the Montreal daily Le Devoir carried a short piece announcing that in eight days, “the radio station CKAC will present for its listeners a new program starring Mme Edouard Bolduc, the popular folklorist,” and “the Soucy-Lafleur trio [see Isidore Soucy*] will take part.” She composed four songs and, on 23 Feb. 1939, she made her last two records. She again toured New England in the autumn of 1939 and undertook her last tour, in Abitibi, in the summer of 1940. Her final show was in Montreal’s Saint-Henri district on 19 December. When it was over, she was hospitalized at the Institut du Radium. Two months later, on 20 February, she died there of cancer.

Recognition

Considered the first singer-songwriter of the chanson québécoise, Mary Bolduc left a repertoire of 102 titles (composed between 1929 and 1939), which include eight songs previously unreleased and 94 recordings (ten works written in collaboration, 76 songs, two pièces turlutées, and six instrumentals). She received many posthumous honours: the City of Montreal named a park after her; the Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste de Montréal awarded her the Bene Merenti de Patria medal in 1991; the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada declared her a national historic person in 1992; the Canada Post Corporation issued a stamp to commemorate the centenary of her birth in 1994; she was inducted into the Canadian Songwriters Hall of Fame in 2003; and the Quebec Ministry of Culture and Communications designated her a person of historic significance in 2016.

Yet in 1941 the press scarcely acknowledged her death. In the 8 March issue of the Montreal magazine Radiomonde, the author and critic Henri Letondal*, the only person who paid tribute to her, announced that “a great artist … has just died.” He added:

Her informal manner, full of gaiety and spirit, earned her standing ovations in Canada and the United States. And yet Mme Edouard Bolduc, an artist of sincerity and integrity, was distrusted by a certain group that valued neither her spontaneous creativity nor the means she used to achieve popularity. However, ordinary people judged her differently[,] with boundless enthusiasm, [and] cheered on [the woman] who knew so well how to entertain them.

Indeed, Bolduc had enjoyed tremendous popular success, as much from the sale of her records as from her sold-out performances. However, members of the elite shunned her, even denigrated her. It was not until her first biography, La Bolduc by Réal Benoit, was published in 1959 in Montreal that her contribution to the French Canadian chanson began to be recognized. In the preface the actor Doris Lussier presented her as “one of the monuments of our folklore.” He rightly appreciated the simplicity of her songs, which “were straightforward, spontaneous, funny, colourful and full of good cheer.” In his opinion, “that is why we remember them. That is why people remember them. Fortunately, they haven’t waited for permission from anguished aesthetes who consider themselves the high priests of Beauty.”

The rediscovery and appreciation of Mary Bolduc’s songs occurred gradually. Towards the end of the 1950s, artists inspired by folk music re-evaluated and revived them. During the Quiet Revolution [see Jean Lesage*], Quebecers embraced them as symbols of patriotism and viewed them as part of their cultural identity. Her recordings were reissued as LPs, and cover versions of her songs were released by several artists, such as Jocelyne Deslongchamps, known as Aglaé, Aimée Sylvestre, known as Dominique Michel, André Gagnon*, Marthe Fleurant, Angèle Arsenault, Yves Lambert, and Jeanne d’Arc Charlebois, as well as by the groups French B. and Loco Locass, which demonstrates their broad appeal. In 1967 Le Magazine Maclean’s included her on the honour roll of “the twenty names, which, in the last century, have been the most significant for French Canada.”

Pioneer and musical style

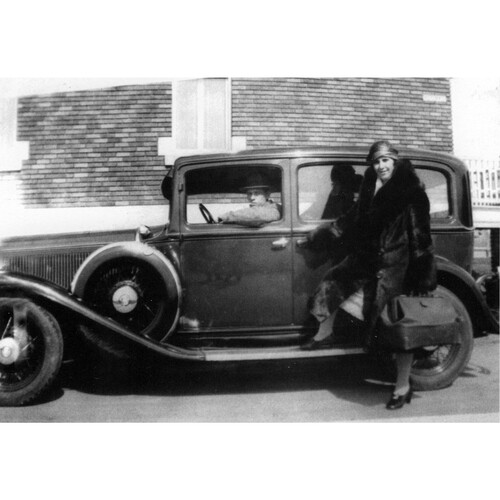

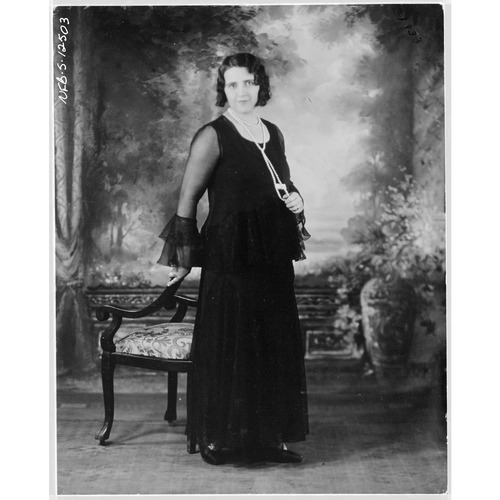

In the 21st century, Mary Bolduc is regarded as a pioneer. A singer-songwriter who managed every aspect of her career and who was also a wife and mother (her correspondence with her husband and children displays her constant anxiety about her household), she had to assert herself in an increasingly urbanized and industrialized province where women did not yet have the right to vote. A model of determination, she was, by virtue of her career, the image of a free, independent woman. For her stage performances she soon began appearing in an elegant black dress and pearl necklace, abandoning the white wig she had worn for Veillées du bon vieux temps. Portraits of the always-smiling young woman posing at the wheel of her car, in a plane, and even on a motorcycle succeeded the promotional photos in which she holds a harmonica, a jew’s harp, or a violin.

Whereas from 1932 onward the male vocal group Quatuor Alouette presented a cappella versions of French Canadian folklore, Mary Bolduc found inspiration in both popular and traditional music, which she made contemporary with original lyrics. She imposed her own style by using a dance rhythm and, especially, a turlute, a vocal technique that involved making onomatopoeic sounds to imitate a musical instrument, a tradition adopted from Scottish, Irish, and Acadian folk music. She drew, often humorously, on subjects from daily life (Tout le monde a la grippe, La grocerie du coin) and current events (L’enfant volé, Toujours “l’R-100”). She sketched portraits of imaginary characters (Jean-Baptiste Beaufouette, Un petit bonhomme avec un nez pointu) and famous ones (Les cinq jumelles [see Dionne quintuplets], Roosevelt est un peu là). She sided with ordinary people (L’ouvrage aux Canadiens, Les colons canadiens) and those in trades (Le commerçant des rues, Les conducteurs de chars), and did not hesitate to take centre stage, usually addressing the audience directly (La morue, La Gaspésienne pure laine, Les souffrances de mon accident). She included a few songs that were bawdy (Fricassez-vous) and some that were festive (Le jour de l’an became a classic).

Bolduc’s songs often reflected traditional values, such as rural life and a woman’s place by her husband’s side, and included advice to girls wishing to marry. She defended her use of the language that was her own: “There are some who are jealous and want to throw a wrench into the works / I tell you that as long as I live I’ll always say moé [meself] and toé [yerself] / I talk like in the old days I’m not ashamed of my old parents / As long as I don’t put in no English I’m not hurting proper French” (La chanson du bavard). She owed her success to her authenticity: a socially committed artist, she sang about what she knew. Her audiences saw themselves in her songs, which drew upon daily life and were tinged with her optimism and joie de vivre. Mary Bolduc expressed her compassion for audience members and gave them a message of hope in songs such as Ça va venir découragez-vous pas: “It’ll come, then it’ll come / But let’s not be discouraged / Me, I always have a merry heart and I carry on with my turlute!”

Ancestry.com, “Quebec, Canada, vital and church records (Drouin coll.), 1621–1968,” Basilique Notre-Dame (Montréal), 24 févr. 1941; Sacré-Cœur-de-Jésus (Montréal), 17 août 1914: www.ancestry.ca/search/collections/1091 (consulted 23 June 2022). Bibliothèque et Arch. Nationales du Québec, Centre d’arch. du Bas-Saint-Laurent et de la Gaspésie–Îles-de-la-Madeleine (Rimouski, Québec), CE102-S13, 4 juin 1894. Musée de la Gaspésie, Centre d’arch. de la Gaspésie (Gaspé, Québec), P11 (Fonds Madame Édouard Bolduc); P78 (Fonds David Lonergan). Library and Arch. Can., “Virtual gramophone: Canadian historical sound recordings”: www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/films-videos-sound-recordings/virtual-gramophone/Pages/virtual-gramophone.aspx (consulted 23 June 2022); “Madame Édouard Bolduc (Mary Travers), folkloriste et chansonnière (1894–1941)”: web.archive.org/web/20220919104801/https:/www.bac-lac.gc.ca/fra/decouvrez/films-videos-enregistrements-sonores/gramophone-virtuel/Pages/mary-bolduc-bio.aspx#queen (consulted 20 May 2025). Bibliothèque et Arch. Nationales du Québec, Instantanés: la vitrine des archives de BAnQ, “L’accident de Mary Travers dite ‘la Bolduc’”: web.archive.org/web/20221129121443/https:/blogues.banq.qc.ca/instantanes/2019/02/20/laccident-de-mary-travers-dite-la-bolduc (consulted 16 May 2025). La Bolduc [Mary Travers], Soixante-douze chansons populaires, Philippe Laframboise, édit. (Montréal, 1992). Pierre Day, Une histoire de la Bolduc: légendes et turlutes (Montréal, 1991). Christine Dufour, Mary Travers Bolduc: la turluteuse du peuple (Montréal, 2001). Phil[ippe] Laframboise, “La belle époque … de la Bolduc,” La Semaine illustrée (Anjou [Montréal]), 30, 31 oct., 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 nov. 1967. P.-M. L[apointe], “1867–1967 / palmarès du siècle,” Le Magazine Maclean (Montréal), 7 (1967), no.1: 14–15. David Lonergan, La Bolduc, la vie de Mary Travers (1894–1941): biographie (Bic [Rimouski] et Gaspé, 1992); new augmented ed. appeared under the title La Bolduc: la vie de Mary Travers (Montréal, 2018). Lina Remon et J.-P. Joyal, Paroles et musiques: Madame Bolduc (Montréal, 1993). Cécile Tremblay-Matte, La chanson écrite au féminin: de Madeleine de Verchères à Mitsou, 1730–1990 (Laval, Québec, 1990).

Cite This Article

Johanne Melançon, “TRAVERS, MARY (LA BOLDUC),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 17, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 31, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/travers_mary_17E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/travers_mary_17E.html |

| Author of Article: | Johanne Melançon |

| Title of Article: | TRAVERS, MARY (LA BOLDUC) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 17 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2025 |

| Year of revision: | 2025 |

| Access Date: | January 31, 2026 |