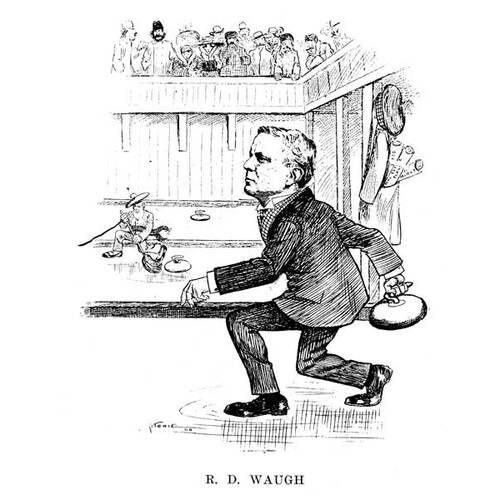

![“Men of Winnipeg in Diamond Jubilee Sketches” Winnipeg Free Press, December 1934. [University of Manitoba Archives & Special Collections,Wpg Elite Study, G. Friesen Fonds, Mss 154, Box 15, File 8] Original title: “Men of Winnipeg in Diamond Jubilee Sketches” Winnipeg Free Press, December 1934. [University of Manitoba Archives & Special Collections,Wpg Elite Study, G. Friesen Fonds, Mss 154, Box 15, File 8]](/bioimages/w600.25489.jpg)

Source: Link

WAUGH, RICHARD DEANS, businessman, public servant, and politician; b. 24 March 1868 in St Boswells, Scotland, son of Richard Waugh* and Janet Deans; m. first 21 Oct. 1891 Harriet Lillie Logan (d. 24 July 1931) in Winnipeg, and they had two daughters and four sons; m. secondly 25 Aug. 1932 Eleanor Mary Lewis in St James (Winnipeg); d. there 20 May 1938 and was buried in St John’s cemetery in Winnipeg.

Education and early career

Educated at Highfield Academy in Melrose, Scotland, young Dick Waugh and his family emigrated to Canada in the early 1880s and settled in Winnipeg. Waugh did not follow his father into agricultural journalism but rather aimed for the learned professions. During the mid to late 1880s he studied law in the office of Chester and David Glass, the latter a prominent lawyer and politician who served as solicitor for the City of Winnipeg. Waugh was never called to the bar but instead went into real estate during the early 1890s, before the rapid expansion of the metropolitan economy after 1895.

Around 1903 Waugh began working for the Minnesota-based Haslam Land and Investment Company’s Winnipeg branch, managed by another resourceful and ambitious Scot, Thomson Beattie. The following year the two bought out the branch’s business and opened as Waugh and Beattie, dealing in real estate and investments, which would become the foundation of Waugh’s success.

Waugh had helped create the Winnipeg Real Estate Exchange in 1903, and five years later he became president of that organization as well as the newly established Western Canadian Real Estate Exchange. He also served as vice-president of the American National Association of Real Estate Exchanges, created in 1908. He had been among the founders of the Winnipeg Development and Industrial Bureau in 1906 and later served as its president. His rapid ascension in the city’s commercial ranks was no doubt facilitated by his marrying a daughter of former mayor Alexander Logan*. He was also connected in legal circles through his brother-in-law, Thomas Graham Mathers, who became chief justice of Manitoba’s Court of King’s Bench in 1910. Waugh had been a founding member of the St Charles Country Club in 1905. A Presbyterian, he was among the organizers of the United Scottish Association in 1918 and served as its president.

Success in business drew Waugh towards municipal public service and politics. His first venture had come in 1904 with his appointment as chair of Winnipeg’s Public Parks Board. Waugh was an ardent sportsman and outdoorsman. He served as president of the Manitoba Curling Association and was made an honorary president of the Winnipeg Cricket Club and the Winnipeg Swimming Club. Recreational public spaces loomed large in his philosophy of civic life, and he was committed to the development of parks, playgrounds, swimming pools, and cycling paths.

Mayor of Winnipeg

In 1908 Waugh was elected to Winnipeg’s board of control, the executive of city government. After serving as secretary of the board, he was elected mayor in 1911, succeeding his friend William Sanford Evans* and defeating Alderman Frank W. Adams. The following year Waugh presided over what historian Christopher Dafoe calls Winnipeg’s “high noon,” the apex of its dramatic pre-war development as Canada’s western metropolis – the “Chicago of the north” as it was known during this period. In August 1912 Waugh was elected second vice-president of the Union of Canadian Municipalities and in November first president of the Western Canada Civic and Industrial League. He was well on his way to becoming one of the best-known and most highly regarded municipal administrators in western Canada.

Waugh was deterred from seeking a second consecutive term as mayor by the tragic death of his business partner, Beattie, on the ill-fated Titanic [see Arthur Godfrey Peuchen*] in April 1912, after which Waugh’s full-time attention turned to his firm. In 1914 Waugh became managing director of the Canadian European Mortgage Corporation. By then a leading member of Winnipeg’s commercial elite, which dominated city government, he was elected mayor by acclamation for 1915 and 1916, succeeding Thomas Russ Deacon*. Canada was in the midst of the Great War, and as a result of war-induced xenophobia, immigrants from eastern Europe fell under suspicion [see William Perchaluk*], while class conflict, which would lead to massive industrial action after the war [see Mike Sokolowiski*], was intensifying. Despite these wartime challenges and the recession, Waugh’s second and third terms were characterized by achievement. In 1915 he became the inaugural chair of the Returned Soldiers’ Association of Winnipeg – forerunner of the Royal Canadian Legion – the first such organization in Canada. As mayor he held a seat on the administration board of the Greater Winnipeg Water District, created in 1913, which oversaw construction of an aqueduct stretching 96 miles and dropping 300 feet from its source at Shoal Lake on the Ontario border. In February 1916, when it was discovered that there were cracks in the aqueduct’s concrete pipe, he successfully defended himself against insinuations by the Winnipeg Telegram that he had known about the problem yet did nothing about it. An official investigation exonerated him. He would see this major municipal infrastructure project to its completion as chair of the water district’s board of commissioners (which reported to the administration board) from 1918 to 1920.

Waugh’s three terms as mayor, though not consecutive, straddled the transition from the city’s boom years to the years of crisis and decline. In 1915 Winnipeg was not the same place it had been in 1912. Despite popular support for Canada’s participation in the Great War, the stresses and strains of the conflict played their part in bringing issues of governance to the fore. In January 1916 Waugh presented a paper on the reform of municipal government at the Ottawa conference of the Civic Improvement League for Canada [see Thomas Adams], which was held in cooperation with the federal Commission of Conservation [see Sir Clifford Sifton*]. He highlighted voter apathy and annual elections as hindrances to effective city governance, stating that “there is just as much room for improvement and reform in those who elect as in those who are elected to manage municipal affairs.” He did not reoffer as mayor for 1917 and never re-entered politics.

First World War

Like many western Liberals, Waugh became a Unionist over the conscription issue and supported the Union government at the Western Liberal Convention in Winnipeg in August 1917. Though he was an ardent recruiter, the death in action of his younger son, Alexander Logan, in December of that year at Cambrai, France, was a crushing blow. The following January, Prime Minister Sir Robert Laird Borden offered Waugh the chairmanship of the Halifax Relief Commission, which was established to help the city recover from the catastrophic explosion of shipboard munitions in the harbour on 6 Dec. 1917 [see Frederick Luther Fowke]. Waugh was keen to accept Borden’s offer, but the Greater Winnipeg Water District would not grant him a leave of absence.

Saar commission

In March 1920 Borden offered, and Waugh accepted, the post of representative of the British empire on the five-member governing commission of the Territory of the Saar Basin, a coal-mining region in the Franco-German border area. This international regime, authorized by part III of the Treaty of Versailles, was instituted by the League of Nations under a 15-year trusteeship commencing in January 1920. Arriving in the territory in April of that year, Waugh was made responsible for finance and food control.

Though very far from being pro-German, Waugh often found himself opposing the punitive attitudes of the French president of the commission and the Belgian and Danish members who sided with him. The fact that Waugh spoke neither French nor German no doubt contributed to his isolation within the commission. The climax of Waugh’s dissent came in March 1923 when, in reaction to a miners’ strike, the commission moved to impose heavy fines and even imprisonment on Saarlanders who criticized the league, treaty, or governing commission. Waugh was the only member to object to the measure. When a second decree prohibiting picketing was issued in May, Waugh disagreed with its permanent nature and abstained from voting on it, although he affirmed that vigorous actions were needed to deal with the strike. His discord with the other commissioners was likely the main reason he resigned in August 1923. According to the commission’s historian, Frank M. Russell, who corresponded with Waugh, “he had come to the conclusion … that the situation in the Saar had become practically intolerable to him.” A staunch supporter of the League of Nations, Waugh was well regarded by both Saarlanders and the council of the league, and his departure was a distinct loss to the commission. He was succeeded by fellow Canadian George Washington Stephens, who afterwards became president of the commission. In Waugh’s obituary, the Winnipeg Free Press recalled that he had said, “It seemed I was always a minority of one, as I thought it my duty to see that the Treaty of Versailles was carried out to the very letter by both French and Germans.” According to author Sidney Osborne, Waugh had been the only member of the commission who was persona grata to the Germans, the reason being that he was the only member of the commission who was not in the pocket of the French government.

Government Liquor Control Commission

The timing of Waugh’s departure from the Saar commission might have been influenced by an employment opportunity at home. In 1923 Premier John Bracken*, to whom Waugh appealed because of his bipartisanship and civic-minded progressivism, appointed him chair of the province’s Government Liquor Control Commission, created that year after a provincial referendum had ended prohibition. Waugh was an ideal candidate: not only was he out of politics, but on matters of public policy his views were well aligned with those of Bracken. Waugh would remain chair until his death in 1938.

In the 1920s Waugh conducted a revealing experiment on transnational shipping costs. He ordered two cartons of whisky from the same Scottish distillery, one to be sent to Brandon via the St Lawrence River and Winnipeg, the other through the Panama Canal to Vancouver and by rail eastwards. The difference in cost proved to be negligible. Waugh’s tenure as chief commissioner saw the creation of a separate liquor licensing board (1928), the amendment of the Government Liquor Control Act (1928), the establishment of licences enabling hotels to sell beer for consumption elsewhere (1934), and the imposition of a retail tariff on beers produced outside Manitoba (1936).

Assessment

The premature and sudden death in January 1938 of Waugh’s eldest son, Richard Douglas, a disabled veteran, inflicted a shock from which Waugh did not recover, and he himself died four months later. Richard Deans Waugh was a typical Scottish “lad o’ pairts.” A largely self-educated and self-made man, he more than made up for what he lacked in formal education thanks to his resourcefulness, discipline, and intelligence. He supported progressive causes, from children’s gardens and good roads to the public ownership of hydroelectric power, and he did not allow partisanship to impede his continual quest for civic improvement. Few municipal public servants in Winnipeg have attracted and retained public confidence to so high a degree. Though a generation removed from Winnipeg’s “founding fathers” [see James Henry Ashdown*], Waugh’s legacy is hardly less significant than theirs.

Richard Deans Waugh is the author of Western Canada, the land of opportunity ([Winnipeg, 1910]), and his paper, “The reform of municipal government,” delivered before the Civic Improvement League for Can. in 1916, is available in Saving the Canadian city: the first phase, 1880–1920, ed. Paul Rutherford (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 1974), 335–40; his extensive papers are held by AM in the Waugh family fonds.

Ancestry.com, “Scotland, select births and baptisms, 1564–1950,” Richard Waugh, Saint Boswells, 24 March 1868. City of Winnipeg, Arch. and Records Control, f00015 (Greater Winnipeg Water District fonds), 1916–20; s00053 (City council minutes), 1908–16; s00057 (Board of Control), 1908–16. Man., Dept. of Justice, Vital Statistics Agency (Winnipeg), no.1891-001331; no.1932-031360; no.1938-020498. Manitoba Free Press, 24 July 1903, 16 July 1908. Winnipeg Free Press, 21 May 1938. A. F. J. Artibise, Winnipeg: a social history of urban growth, 1874–1914 (Montreal and London, 1975). R. C. Bellan, “The development of Winnipeg as a metropolitan centre” (phd thesis, Columbia Univ., New York, 1958). Jim Blanchard, Winnipeg 1912 (Winnipeg, 2005); Winnipeg’s Great War: a city comes of age (Winnipeg, 2010). J. M. Bumsted, Dictionary of Manitoba biography (Winnipeg, 1999). Canadian annual rev., 1912–38. Canadian who’s who, 1910–36. Directory, Winnipeg, 1880–1920. D. A. Ennis, “Developing a domestic water supply for Winnipeg from Shoal Lake and Lake of the Woods: the Great Winnipeg Water District aqueduct, 1905–1919” (msc thesis, Univ. of Manitoba, Winnipeg, 2011). Henry Huber, “Winnipeg’s age of plutocracy, 1901–1914: a biographical study of Winnipeg’s mayors … from the beginning of the twentieth century to the beginning of World War I” (n.p., 1971; unpublished paper, copy in author’s possession), 24–26. Alan Hustak, Titanic: the Canadian story (Montreal, 1998). J. [E.] Kendle, John Bracken: a political biography (Toronto, 1979). Man., Government Liquor Control Commission, Annual report (Winnipeg), 1924–39. Manitoba, pictorial and biographical (2v., Winnipeg, 1913), 1: 265–68. Man., Statutes, 1913, c.22. Sidney Osborne, The Saar question: a disease spot in Europe (London and Woking, Eng., 1923). Pioneers and prominent people of Manitoba, ed. Walter McRaye (Winnipeg, 1925). F. M. Russell, The international government of the Saar (Berkeley, Calif., and London, 1926); The Saar: battleground and pawn (Stanford, Calif., 1951); “The Saar Basin Governing Commission,” Political Science Quarterly (New York), 36 (1921): 169–83. J. H. Thompson, “The harvests of war: the prairie west, 1914–1918” (phd thesis, Queen’s Univ., Kingston, Ont., 1975). L. M. Vallely, “George Stephens and the Saar Basin Governing Commission” (phd thesis, McGill Univ., Montreal, 1965).

Cite This Article

Barry Cahill, “WAUGH, RICHARD DEANS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 24, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/waugh_richard_deans_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/waugh_richard_deans_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Barry Cahill |

| Title of Article: | WAUGH, RICHARD DEANS |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2025 |

| Year of revision: | 2025 |

| Access Date: | February 24, 2026 |