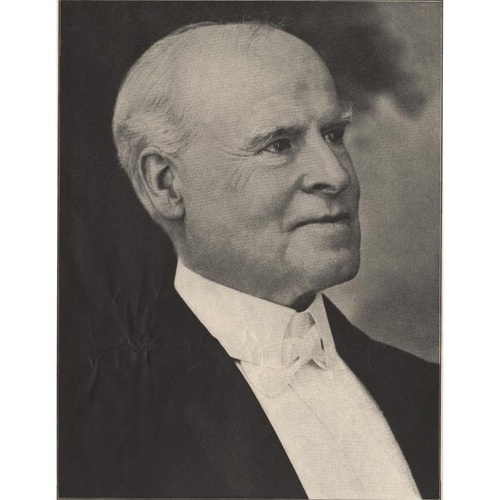

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

BENGOUGH, JOHN WILSON, cartoonist, editor, publisher, author, entertainer, and politician; b. 7 April 1851 in Toronto, son of John Bengough and Margaret Wilson; m. there first 30 June 1880 Helena (Nellie) Siddall (d. 1902); m. secondly 18 June 1908 Mrs Annie Robertson Matteson in Chicago; there were no children of either marriage; d. 2 Oct. 1923 in Toronto.

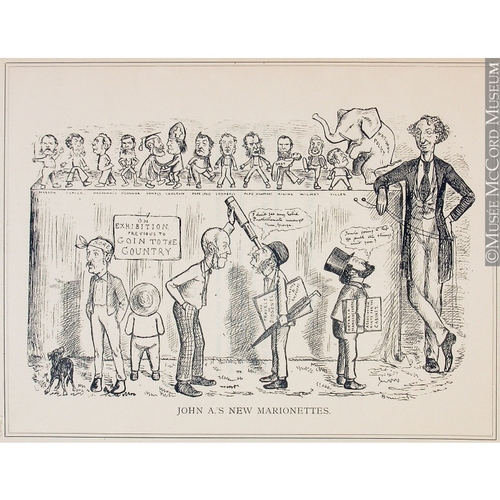

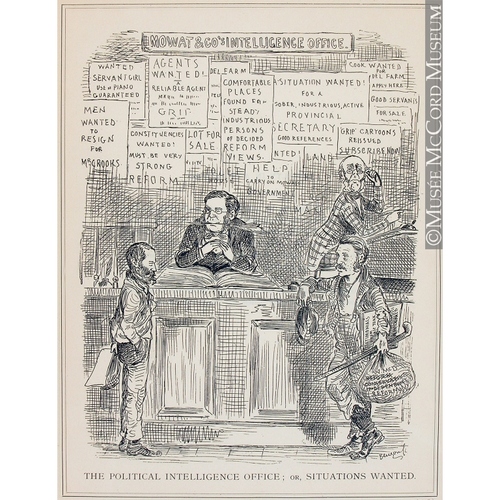

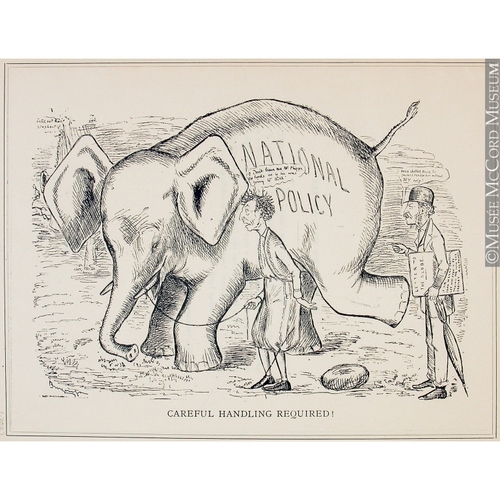

On 24 May 1873, at the age of 22, John Wilson Bengough published the first issue of Grip. For the next two decades this Toronto weekly would carry puns, jokes, satire, and especially cartoons about virtually every topic of the day in late-19th-century Canada. The name Grip was borrowed from the raven who regularly accompanied the feeble-minded central character of Charles Dickens’s 1841 novel Barnaby Rudge, while the magazine itself was probably modelled on Punch (London), whose cartoonist, John Tenniel, Bengough greatly admired. Bengough edited and published this little magazine; his voice dominated its pages through reams of poetry, outrageous puns, satirical paragraphs, and “Croaks and Pecks” of the raven. His humour was often broad: “To cultivate a Canadian National Spirit. – Grow barley,” or “A Fenian Scare – threatened lack of whiskey.” Above all, however, Grip featured Bengough’s cartoons and caricatures. Some were large enough to fill an entire page and many revealed the influence of Thomas Nast, the great Republican cartoonist of Harper’s Weekly (New York); Bengough turned Nast’s Republican elephant into a symbol for Sir John A. Macdonald*’s National Policy, for instance. Others, which appeared in odd corners almost as fillers, were little gems of social and personal commentary.

“The Pun,” Grip proclaimed, “is mightier than the Sword,” for Bengough’s humour was purposeful. In 1888 he explained “that the legitimate forces of humor and caricature can and ought to serve the state in its highest interests, and that the comic journal which has no other aim than to amuse its readers for the moment, falls short of its highest mission.” The humorist was also a moralist intent upon both amusing and instructing his readers. Given his background and beliefs, this penchant is not surprising.

Bengough’s family circumstances were modest and so was his education. His immigrant parents, a Scottish cabinetmaker and his Irish wife, sent him to the common and grammar schools of Whitby, where the family lived for a time; he was then briefly articled to a local lawyer. After learning something of the printing trade at the Whitby Gazette, he moved on to Toronto where he became a junior reporter with George Brown*’s Globe in 1871 or 1872. This early association with Liberal party journalism was natural enough since his father was a known party worker. Though Bengough would loudly declare Grip’s political disinterestedness and sometimes throw his support behind independent candidates or representatives of Alexander Sutherland*’s Third Party, he always came back to the Liberal party, especially in the years after Grip’s demise. His cartoons would appear in a great variety of publications at home and abroad, but Liberal newspapers and party publications provided him with much of his income. His ambition to become a Liberal member of the Senate was gently rebuffed by Sir Wilfrid Laurier*; he nevertheless remained loyal.

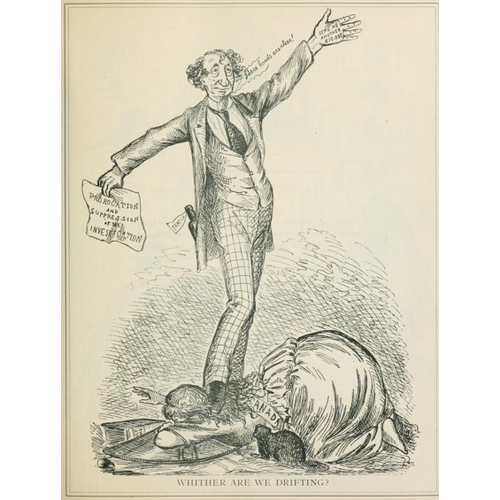

Grip’s politics, during its earliest years, remained undefined. Frequent gibes at George Brown allowed it to claim independence. On the other hand, the weekly showed no sympathy for the Conservatives, particularly after the Pacific Scandal of 1873 offered Bengough an opportunity to express unlimited moral outrage – especially pictorially. Indeed, it was that controversy which provided Grip with an opportunity to win a wide audience. Bengough’s often reprinted cartoons from this period captured the essence of John A.’s physiognomy: his prominent nose, sly eyes, fashionable coiffure, and nonchalant attitude contrasted, for example, with Alexander Mackenzie*’s upright Scottish Presbyterian mien. “I admit I took the money and bribed the electors with it,” Bengough’s Macdonald remarks. “Is there anything wrong about that?” The question was certainly rhetorical.

Though Bengough continued to direct his verbal and pictorial gibes at the Conservatives – Macdonald would remain his favourite target until his death in 1891 when Bengough published a poetic tribute – the 1880s saw the flowering of Grip’s own reformist platform. It was founded upon Bengough’s religious outlook and drew on a variety of ideas that were common to late-19th-century social critics in the English-speaking world. These reform nostrums, which Bengough propagated but did not originate, advocated social regeneration through the adoption of attitudes and policies sometimes described as applied Christianity or the Social Gospel.

Bengough’s own religious upbringing was Presbyterian but he apparently imbibed few of the distinctive doctrines of that denomination. Instead, at least in his mature years, his religion eschewed doctrine in favour of ethics. Like many other social reformers he believed that theologically informed preaching reflected conservative other-worldliness while moralistic preaching concerned the here and now. He made his position plain in an 1875 poem criticizing churches, “Whose preachers preach theology a deal more than they should,/And try to make men wise when they should try to make them good.”

This moralistic religion was not based on any sophisticated understanding of the intellectual currents which challenged religious orthodoxy in the late 19th century. Bengough rejected the claims of the “higher critics” who questioned literal readings of the Bible, and of Darwinians whose scientific materialism raised even more radical doubts about religion. In a satirical poem entitled “The higher criticism” Bengough professed his continuing adherence to the simple religious truths he had learned from his mother. Creations such as Professor Spencer E. Volushin and the Very Reverend Archdeacon Diaphanous Dixie, dd, were used by Grip to expound the simple moral claim that right conduct, not doctrinal purity, was the true test of religious convictions. It is not difficult to understand why writers like Charles Dickens would appeal to the Toronto cartoonist.

Bengough’s platform contained a number of planks familiar to contemporary moral reformers. He ardently advocated the prohibition of alcoholic beverages, believing that they took a particularly heavy toll among working people. It was also in the interest of this class that he opposed Sunday streetcars, which he thought would destroy the sabbath as a day of rest. So, too, in the 1880s he took up the cause of women’s suffrage and the admission of women to such professions as the law, reversing his earlier opposition to “The Female Righter.” But Bengough went beyond these modest demands for change, perhaps because he increasingly realized that such social sins as alcohol consumption had their roots in more fundamental problems. By the 1880s Bengough had discovered, and accepted, the analysis of the ills of emerging industrial capitalism presented by the American social critic Henry George. In Progress and poverty (1879) George, whose moralistic language appealed to Bengough, explained that the existence of poverty in the midst of the plenty created by science and technology was the result of an inequitable fiscal system. This system failed to tax the unearned increment on land whose value increased not through the owner’s labours, but rather as a consequence of increased demand arising from population growth. At the same time the protective tariff promoted monopoly and increased prices unnaturally. George’s alternative, what Bengough would call “The Whole Hog Solution,” was obvious: a single tax on unimproved land values and free trade. Once he had discovered George’s teachings Bengough became a lifelong missionary in the single-tax cause, cartooning, writing, and speaking across Canada and as far away as Australia in the hope that its adoption would regenerate industrial society, “this travesty of Christianity.” Advancing his single-tax beliefs Bengough attacked Macdonald’s National Policy, thundered against monopolists, took up the cause of farmers and workers, and excoriated all those – including his friend Principal George Monro Grant* of Queen’s College in Kingston and his enemy Goldwin Smith* – who were blind to the Georgite light. In this crusade he was joined by a sprightly band of regenerators which included Thomas Phillips Thompson*, a Bellamyite socialist, Samuel Thomas Wood*, an economics and nature writer for the Globe, and other members of the Toronto Anti-Poverty Society, the Knights of Labor, and the Patrons of Industry.

Grip’s “Solid Platform” included several other items that revealed a harsher side to Protestant reformism, and Bengough’s support for “Anglo-Saxon” nationalism. He promoted independence under a republican form of government and the alliance of all Anglo-Saxon nations, rejecting both Lieutenant-Colonel George Taylor Denison’s “Imperial Federation” and Goldwin Smith’s annexationism while accepting their common belief in Anglo-Saxon solidarity. His advocacy of the complete separation of church and state and of English as the one official language, obviously directed at Roman Catholics and French Canadians, was a stark manifestation of his ethnic nationalism. He looked forward to the day “when the monstrosity of a double official language and dual schools will be done away with throughout the whole country. Our real national life will date from that day.” While Bengough deplored the social and economic deprivations suffered by Canada’s native peoples, he had only scorn for Louis Riel*’s effort to unite Métis and native people in the 1885 rebellion. His special Canadian Pictorial and Illustrated War News was bombastically nationalistic, as was his poem celebrating Major-General Frederick Dobson Middleton*’s victory at Batoche (Sask.):

Who says that British blood grows tame,

Or that the olden fire is gone,

Must first forget Batoche’s name,

And how that day was fought and won!

Grip strongly supported Riel’s death sentence, adding, however, that the real authors of the rebellion should be “exposed and punished whether they turn out to be plotting speculators at Prince Albert or drowsy Ministers at Ottawa.”

Assessing Grip’s public impact or financial condition is extremely difficult since accurate records are lacking. In the mid 1880s, at its peak, it claimed a paid circulation of 7,000 to 10,000 and 50,000 readers, and there is evidence that the country’s leaders paid it some attention. Then published by Grip Printing and Publishing Company, of which Bengough was a director, it had been through a series of partnerships in which Bengough was associated first with Andrew Scott Irving*, then with his brother George, and finally with his brother Thomas and Samuel John Moore*. But its existence was always precarious and the depression of the early 1890s spelled its death. Bengough gave up the editorship in 1892 when new management appointed T. Phillips Thompson to the post. A year later Bengough returned but he failed to revive his creation.

During the next quarter-century Bengough maintained a public profile through his cartoons in a wide variety of publications: the Toronto Globe, the Toronto Daily Star, the Montreal Star, and Saturday Night (Toronto). His work also appeared in such single-tax publications as the Public in Chicago and the Square Deal in Toronto. He attracted large audiences to his “chalk talks,” which he had begun in 1874 and which took the main elements of Grip – cartoon, puns, satire, and advocacy of social reform – and put them on stage in numerous large and small Canadian communities as well as in the United States, Great Britain, Australia, and New Zealand. Then there were his numerous publications. The two-volume Caricature history of Canadian politics (1886) reproduced many of Grip’s finest political cartoons. The gin mill primer (1898) presented the Prohibition case, and The up-to-date primer (1896) and The whole hog book (1908) were single-tax tracts. Chalk talks (1922) brought together many of his most popular illustrated lectures and set out his reform philosophy. Finally there were the poetry collections, Motley: verses grave and gay (1895) and In many keys: a book of verse (1902), which brought together largely unmemorable verse of humour, political satire, pathos, religious sentimentalism, and patriotism.

Since Bengough the journalist had always focused on politics, it was natural that he should be drawn directly into public life. In the 1890s he served as president of the Toronto Single Tax Association and was active in the People’s Forum; later he joined the Canadian Peace and Arbitration Society and became a director of the Toronto Industrial Exhibition. In 1907 he won election as alderman for Toronto’s Ward 3, and he was re-elected in 1908 and 1909. This new pulpit provided him with an opportunity to preach and promote causes with which he had long been identified: tax reform, tenant’s rights, sanitary improvement, public ownership of hydroelectricity, and the restriction of liquor licences. Perhaps frustrated by his failure to win much support for some of these reforms, he left council before the completion of his third term in order to return to the lecture circuit.

Though Bengough’s career as a public figure had passed its peak when Canada entered the war in 1914, he had by no means fallen silent. He now turned his talents to promoting the war effort, including support for conscription as the clearest expression of patriotism, a position taken by many English-speaking reformers. Nevertheless, he remained faithful to the Liberal party and especially to William Lyon Mackenzie King*, whose Industry and humanity . . . (1918) Bengough enthusiastically praised. In the 1921 election he applied his cartooning skills to support the new Liberal leader. He then returned to the lecture platform. In 1922, following a strenuous western tour, he travelled to the Maritimes where he collapsed during a performance in Moncton, N.B. He died suddenly the following year at his home at 58 St Mary Street while working on a cartoon supporting an anti-smoking campaign. He had never deserted the good old cause of moral reform.

Bengough’s reputation rests mainly on his greatest achievement, Grip, and the cartoons he sketched for the witty little reformist magazine that flourished in dour late-Victorian Toronto. He was not a great artist; his cartoons, though often well drawn, were too crowded and he rarely resisted the temptation to explain and preach. A few of his most striking images he borrowed from others, but the cartoons he published under the pseudonym L. Côté demonstrated that he could draw in contrasting styles. He had a talent that fixed, probably forever, the historical image of numerous public figures of his time, most notably Sir John A. Macdonald. He also had a passionately held viewpoint which gave his cartoons an edge that both simplified issues and ensured that his readers were drawn into his vision of moral conflict. Principal Grant came close to the mark when he said of Bengough, “You may think him at times Utopian. . . . In the best sense of the word, he is religious.” A punster with a vision of “thingsastheyoughttobe.”

[The J. W. Bengough papers, largely composed of drafts of articles and speeches and clippings from various sources, are held at the McMaster Univ. Library, Div. of Arch. & Research Coll., Hamilton, Ont.

Bengough’s major publications, other than Grip (1873–94), include: The Grip cartoons, vols. I and II, May 1873 to May 1874 (Toronto, 1875); The decline and fall of Keewatin: or, the free-trade redskins; a satire (Toronto, 1876); Bengough’s popular readings: original and select (Toronto, 1882); A caricature history of Canadian politics . . . (2v., Toronto, 1886; an abridged one-volume edition, selected and introduced by Douglas Fetherling, was published in 1974); The Prohibition Aesop: a book of fables, published in Hamilton some time between 1889 and 1897; The up-to-date primer . . . (New York and Toronto, 1896; reprinted with an introduction by Douglas Fetherling, 1975); The whole hog book: being George’s thoro’ going work “Protection or free-trade?” rendered into words of one syllable, and illustrated with pictures; or, a dry subject made juicy (Boston, 1908); and Bengough’s chalk talks: a series of platform addresses on various topics, with reproductions of the impromptu drawings with which they were illustrated (Toronto, 1922).

Among secondary sources, Stanley Paul Kutcher’s dissertation “John Wilson Bengough: artist of righteousness” (ma thesis, McMaster Univ., 1975), is the most complete. Carman Cumming, Sketches from a young country: the images of “Grip” magazine (Toronto, 1997) is a critical examination of Grip’s journalism, while Ramsay Cook, The regenerators: social criticism in late Victorian English Canada (Toronto, 1985), places Bengough in context with his contemporaries. r.c.]

AO, RG 22-305, nos.15572, 48698; RG 80-5-0-94, no.13355; RG 80-8-0-262, no.3212; RG 80-8-0-912, no.6264. Daily Mail and Empire, 3 Oct. 1923. Globe, 2 July 1880. World (Toronto), 19 June 1908.

Cite This Article

Ramsay Cook, “BENGOUGH, JOHN WILSON,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 13, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bengough_john_wilson_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bengough_john_wilson_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Ramsay Cook |

| Title of Article: | BENGOUGH, JOHN WILSON |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | February 13, 2026 |