Source: Link

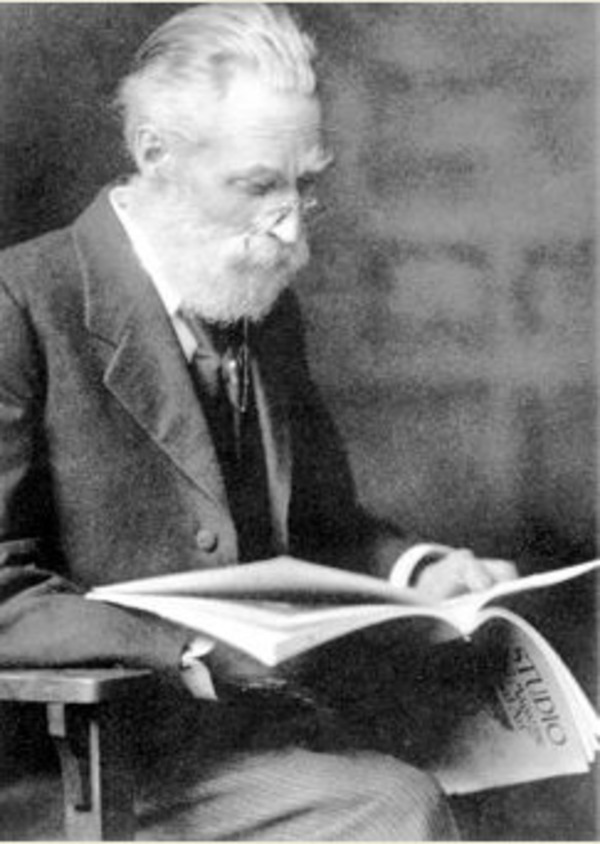

THOMPSON, THOMAS PHILLIPS, journalist, political activist, editor, writer, and labour reformer; b. 25 Nov. 1843 in Newcastle upon Tyne, England, elder of the two sons of William Thomas Thompson and Sarah Robson; m. first 2 March 1872 Delia Florence Fisher (d. 3 Nov. 1897) in Guelph, Ont., and they had one son, who died in childhood, and three daughters; m. secondly 1899 Edith Fisher, and they had one son; d. 20 May 1933 in Oakville, Ont.

Phillips Thompson was, according to writer A. B. McKillop, “the best known political satirist, socialist intellectual, and champion of labour in the country.” Phillips, who was called Tom in his youth, emigrated to Upper Canada with his parents when he was a teenager. After short stays in Belleville and Lindsay, the Thompsons settled in St Catharines. Tom studied law and worked for the same insurance company as his father before deciding to pursue a career in journalism. His earliest political work was an 1864 pamphlet titled The future government of Canada. At a time when confederation was a major subject of debate, Thompson argued against the monarchical government urged by politician Thomas D’Arcy McGee*, favouring instead a “British American independent republic.” He also contended that the cultural assimilation of French Canadians was essential to the future nation’s survival, although he would become more sympathetic towards them in later life.

In April 1866 Thompson took a job as an editor for the St Catharines Post, and in June he covered the Fenian raids [see Alfred Booker*] as a correspondent for the Montreal Herald. He became engaged to a local girl; it is unclear when or why the arrangement was broken off. He moved to Toronto the following year to work for John Ross Robertson*’s Daily Telegraph as a police-court reporter. In 1872 he joined the Toronto Mail [see Josiah Blackburn*; John Riordon*], where he wrote political satire under the pseudonym Jimuel Briggs. His weekly columns proved so popular that a year later they were published as The political experiences of Jimuel Briggs, d.b., at Toronto, Ottawa and elsewhere. By awarding his alter ego a “d.b.” (Dead Beat) and by making his alma mater the fictional Coboconk University, Thompson was undoubtedly poking fun at the intellectual pretensions of many late-19th-century social reformers. His quick wit was also showcased in Grip, which cartoonist John Wilson Bengough* set up in 1873 with his assistance, and with which Thompson would be intermittently associated over the next two decades.

In 1874 Thompson helped found the National, a weekly journal that supported the Canada First movement [see William Alexander Foster*]. Historian George Ramsay Cook* argues that Thompson wanted to use the National to convert Canada First “from an intellectual coterie into a popular movement,” and that the establishment of the paper marked the first stage of his transformation into a labour activist. Thompson moved to Boston in 1876 to work for the local Traveller, and during his stint there he became familiar with American left-wing thought. He returned to Toronto three years later and began writing for the Mail, his former employer, and the Globe, which soon sent him overseas to cover the Irish National Land League, a mass organization of tenant farmers protesting high rents. Angered by the injustice of what he saw and heard, he developed radical views on social reform, at least partly because the assignment gave him the opportunity to meet and interview the American writer Henry George, whose 1879 book Progress and poverty popularized the argument that a single tax on the unimproved value of land would stop the inflation of real-estate values in urban areas, lower the cost of housing, and thereby better the lives of working people. Thompson’s reports on the Irish situation, and on George’s ideas, were well received at home, and the Globe reprinted them in January 1882.

Thompson’s career was now flourishing. In 1883 he took up an editorial position with Edmund Ernest Sheppard*’s Toronto Evening News and, at the same time, began writing as Enjolras (the radical student leader in Victor Hugo’s Les misérables) in the weekly Palladium of Labor, the journal of the Knights of Labor in Hamilton [see Kate McVicar*]. In 1887, after George helped him find a publisher in New York, Thompson released a monograph, The politics of labor. Soon afterwards he became assistant editor at Grip, and he was its editor between 1892 and 1894. In all of these publications, as well as the Labor Advocate (1890–91), he clearly expressed his political, economic, and social views.

One of the first Canadian critiques of the capitalist system, The politics of labor was Thompson’s most important work. The basis of the philosophy he expressed in its pages was his belief that the individual liberty of labourers had been destroyed by competition for wage labour created by industrialism, and by monopoly capitalism. The former undermined what he considered to be their traditional social position, while the latter eliminated economic opportunities that had previously allowed them to escape the slavery of wage labour. “Monopoly above and competition below,” Thompson wrote, “are the upper and nether millstones between which the toiler is crushed.” Like Henry George, he identified monopoly landownership as the most direct cause of society’s problems, and he particularly opposed land grants to large corporations such as railways, arguing that these grants restricted workers’ access to land and therefore hampered their ability to make economic progress. Until the problem of monopoly landownership was resolved, he believed, ameliorative steps such as higher wages for labourers would ultimately fail because landowners would simply raise rents to take advantage of their tenants’ greater wealth. When he testified in November 1887 before the royal commission on the relations of labor and capital, chaired by James Sherrard Armstrong*, Thompson maintained that rapid increases in the cost of rental properties in Toronto had brought “considerable hardship upon a good many of those who have only fixed incomes or salaries.”

Thompson’s proposals for reform incorporated a variety of social and political views. He expanded George’s concept of the “unearned increment,” money that accrued to landlords from rising land values rather than from their own exertions, to include all aspects of industrial life, not just landownership. In an 1886 Palladium editorial he reasoned that before a millionaire “could have any chance to utilize his business talents, he must first have a society with all the highly complex agencies and instrumentalities of commercial life, in which these qualities can find free scope.” Because he owed his success to society, his wealth was therefore a resource that belonged to society, and its people had “the right to step in and put a limit upon accumulation – to fix the amount which any one individual should control, and by a system of graded taxation to appropriate a large share of these fortunes to public uses.”

Thompson believed it was necessary for society to be improved through an evolutionary, rather than a revolutionary, process. Sudden changes would lead to anarchy, which would merely allow a new group of monopolists to take over. To achieve lasting change, it was essential to alter the way people thought about their roles in society. The challenge was, as Thompson put it in 1885, “to eradicate the deep-rooted selfishness begotten of competition and to instill in its place a love for humanity and a strong sense of justice.” His vision of socialism called for the elimination of wasteful competition through the gradual expansion of public control over production and distribution by industries. In addition, the government would eventually nationalize land, establish wage regulations, and create a universal old-age pension. This “cooperative system” would make “government and society one immense joint stock company for carrying on the work of the country.” Instead of being forced to pay “tribute to a few greedy employers,” Thompson predicted, every man would receive “his share of the proceeds of the industry in which he is engaged according to his real earnings.” In this scenario the “really necessary Labor of the world, all men being workers, could probably be done in three or four hours a day.”

In addition to being a socially conscious journalist, Thompson became an active participant in the labour movement and in electoral politics. Among his most important associates were printer Daniel John O’Donoghue*, painter Charles March*, tailor Alfred Fredman Jury*, and machinist David Arthur Carey*. In July 1886 he joined Victor Hugo Local Assembly 7814 of the Knights of Labor, and he represented it at the Trades and Labor Congress of Canada that year. Thompson encouraged fellow “brainworkers,” whom he described in an 1884 Palladium article as “clerks, book-keepers, salesmen, journalists and many other classes of ill-paid and hard-worked employees,” to unite with manual labourers in the fight for reform. “Those who live by the use of their brains in the service of others,” he claimed, “are subject to precisely the same disabilities as those who work with their hands.” He penned The Labor reform songster, a collection of militant inspirational songs that the Knights of Labor published in 1892. Thompson, who knew the value of clearly expressing complex ideas and strove to appeal to a wide audience, was also an effective public speaker.

In keeping with his desire to engage and mobilize the working class, Thompson urged the creation of a labour party, based on “the right of society to control production,” that was independent of the Liberals or Conservatives. Loyalty to the old parties served only to divide workers, he reasoned, and even hybrid candidates (such as those who ran under a Liberal–Labour banner) were ultimately detrimental to the cause of reform: “Any good they can do will be counterbalanced by the strife their political predilections will stir up and the prejudice which their party leanings will create.” He believed that Canadian democracy was controlled by “professional politicians and little rings and cliques,” and that as a result citizens were subject to the arbitrary decrees of monopolists. “In questions which vitally affect the lives and welfare of the people, such as those of work and bread, and just distribution of products,” Thompson argued in the Labor Advocate, “we have no government.” In 1892–93 he acted on his principles by running, albeit unsuccessfully, in two provincial by-elections under the banner of Labor Reform.

In the early 1890s Thompson became a strong advocate of the ideas of Edward Bellamy, an American socialist. Bellamy’s utopian novel, Looking backward, 2000–1887 (Boston, 1888), inspired the formation of what he called “nationalist” associations across North America that urged the nationalization of industry. The influence of this book can be seen in the editorials Thompson wrote for the Labor Advocate. His name appeared several times in the New Nation, Bellamy’s journal, and he used the Canada Farmers’ Sun, founded by George Weston Wrigley*, to propagate the American’s ideas. Thompson was also a member of the Toronto Nationalist Association and served as its president in 1893–94. Bellamy’s theories did not alter Thompson’s own well-established views on social reform; rather, they provided him with a vision of how a utopian society could be created through a series of practical evolutionary steps, such as the expansion of municipal services.

Thompson expected that nationalization would occur naturally because of the inherent inequities in the industrial system. Wealth would become more concentrated, and as a result monopolists would increasingly be exposed to social criticism. Support for reform would increase, and the process would become self-perpetuating. “Trusts and combines are fast making the nationalization of industry possible,” he explained, “and the more oppressive and greedy they are the more quickly the people will be forced for their own protection to assume the control of all enterprises in which they are concerned.” Gradually, the “ideal industrial commonwealth” would emerge.

Thompson’s views on social reform had a spiritual side. He was born into a Quaker family, but like many within the 19th-century social-reform movement, especially those who favoured Bellamy’s nationalism, he became attracted to theosophy, which rejected traditional religion in favour of searching for universal truth and human brotherhood. He had been one of the first members of the Toronto Free Thought Association founded in 1873, and he joined the Toronto Theosophical Society in 1891. In the following years his views on social issues were imbued with spirituality. “Our present villainous social system is mainly due to the wrong and misleading theological ideas which are reflected in existing political and social institutions,” he wrote in 1903, “and we cannot expect much change for the better until we substitute more ennobling and correct views of man’s relationship to the unseen world, his ultimate destiny and his relation to his fellows.” Thompson’s unconventional beliefs influenced his personal life. Shortly after the death of his first wife, Delia, in 1897, he married her younger sister, Edith. The union of a widower and his wife’s sister was forbidden by the Church of England, to which Edith’s family adhered, but the stricture evidently did not trouble her new husband, who had by this time become an atheist.

Relatively little is known about Thompson’s domestic circumstances, but it is clear that his fame as a social reformer never translated into prosperity for his family. It became progressively harder for him to find steady work with newspapers, most of which were staunchly Liberal or Conservative, and in the mid 1890s the Thompsons lived in what McKillop describes as “genteel poverty,” dwelling in a modest Toronto home that had a pleasant exterior but lacked running water and was insufficiently insulated from the winter cold. Thompson’s status in labour circles helped him to find jobs: from 1895 to 1905 he wrote reports for the provincial governments of Arthur Sturgis Hardy* and George William Ross*, and from 1900 to 1911 he was the Toronto correspondent of the Labour Gazette, published by the federal Department of Labour [see William Lyon Mackenzie King*]. In spite of his mainstream connections, he continued to write for leftist newspapers such as the Vancouver Western Clarion and the Toronto Toiler, and from at least 1904 he was a correspondent for trade and technical journals based in the United States and England. He also became the secretary and organizer of the Ontario Socialist League in 1902, and every year from 1904 to 1907 he was an unsuccessful Socialist Party candidate for the Toronto Board of Education (his final run was with James Simpson, who would later become mayor).

In 1912, at the age of 68, Phillips Thompson retired from government employment and moved to Oakville. He continued to involve himself in public debates. He was an outspoken isolationist and pacifist during World War I and remained active in socialist organizations in Ontario into the 1920s, at which time he began to suffer from progressive blindness. In spite of this disability he continued to be a correspondent for various trade journals, and he found time to compose whimsical poems for his grandchildren Lucy Florence Beatrice and Pierre Francis de Marigny Berton*, the future journalist and historian. In 1927 Thompson joked to Lucy that if he lived to be 100, “then a real antique will I be.” Five years later, on turning 89, he happily reported, “We had a merry birthday party / With music song and laughter hearty … / And so with confidence and cheer, I enter on my ninetieth year.” After he died of heart failure on 20 May 1933, obituaries acknowledged Thompson as one of Canada’s most influential labour writers of the late 19th century.

Christopher O’Shea in collaboration with Christopher Pennington

Thomas Phillips Thompson is the author of The future government of Canada … (St Catharines, Ont., 1864), The political experiences of Jimuel Briggs, d.b., at Toronto, Ottawa and elsewhere (Toronto, 1873), The politics of labor (New York and Chicago, 1887), and The labor reform songster (Philadelphia, 1892). A prolific writer and editorialist, he contributed over the course of his career to numerous periodicals in Toronto, including the Daily Telegraph, Evening News, Grip, Labor Advocate, Mail, and National. He also wrote for the Palladium of Labor (Hamilton, Ont.), New Nation (Boston), Canada Farmers’ Sun (London, Ont., etc.), and Labour Gazette (Ottawa). No complete collection of his journalistic works exists, however. Thompson’s 1887 testimony on the cost of rental properties in Toronto can be found in Can., Royal commission on the relations of capital and labor in Canada: Report: evidence – Ontario (Ottawa, 1889), 98–103.

At the William Ready Div. of Arch. and Research Coll., McMaster Univ. (Hamilton), the Thompson family fonds contains valuable information about Thompson’s family background and early career; the Pierre Berton fonds, ser.1, box 339, file 19, has poems Thompson wrote to his grandchildren, two of which, dated 15 July 1927 and 29 Nov. 1932, are quoted in the biography. The T. Phillips Thompson fonds (F 1082) at AO and the Phillips Thompson fonds (R7667-0-5) at LAC consist of some of his business and personal correspondence.

The genealogy of the Thompson family is documented in L. B. Woodward, The Thompsons of Morland in Canada … (White Rock, B.C., 2003). Basic biographical entries on Thompson may be found in D. J. Bercuson and J. L. Granatstein, The Collins dictionary of Canadian history, 1867 to the present (Don Mills [Toronto], 1988); Historica Canada, “Canadian encyclopedia”: www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca (consulted 2 March 2017); Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898 and 1912); and Wallace, Macmillan dict. The best secondary sources on Thompson are Jay Atherton, “Introduction,” in T. P. Thompson, The politics of labor (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., [1975]), which provides a good biographical overview; Russell Hann, “Brainworkers and the Knights of Labor: E. E. Sheppard, Phillips Thompson and the Toronto News, 1883–1887,” in Essays in Canadian working-class history, ed. G. S. Kealey and Peter Warrian (Toronto, 1976), 35–57; [G.] R. Cook, The regenerators: social criticism in late Victorian English Canada (Toronto, 1985), which examines Thompson’s involvement with various social-reform organizations; G. S. Kealey, Toronto workers respond to industrial capitalism, 1867–1892 (Toronto and Buffalo, 1980), which looks at his connection to the Toronto Nationalist Assoc.; and A. B. McKillop, Pierre Berton: a biography (Toronto, 2008). Other useful sources are Carman Cumming, Sketches from a young country: the images of “Grip” magazine (Toronto, 1997), and Ian McKay, Reasoning otherwise: leftists and the people’s enlightenment in Canada, 1890–1920 (Toronto, 2008). An extensive discussion on Thompson can be found in Christopher O’Shea, “T. Phillips Thompson’s reformism (1883–1892): the Palladium of Labor, the Labor Advocate and the influence of Edward Bellamy” (ma cognate essay, Wilfrid Laurier Univ., Waterloo, Ont., 1997). Thompson is mentioned in various other works concerning Canadian labour history, but many are dated and provide only a cursory, often inaccurate, assessment.

Cite This Article

Christopher O’Shea in collaboration with Christopher Pennington, “THOMPSON, THOMAS PHILLIPS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 16, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/thompson_thomas_phillips_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/thompson_thomas_phillips_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Christopher O’Shea in collaboration with Christopher Pennington |

| Title of Article: | THOMPSON, THOMAS PHILLIPS |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2020 |

| Year of revision: | 2020 |

| Access Date: | February 16, 2026 |