Source: Link

RINDISBACHER, PETER, painter; b. 12 April 1806 in Eggiwil, Switzerland, second son of Pierre Rindisbacher and Barbara (Barbe) Ann Wyss; d. 12 or 13 August 1834 in St Louis, Mo.

Peter Rindisbacher’s family were German-speaking members of the Reformed Church. His father was a middle-class farmer who began to work as a veterinarian in 1806. Peter sketched continuously from a very early age, and was encouraged and supervised by his parents. In 1818 he briefly received instruction in landscape painting from Jakob Samuel Weibel, a Bernese school miniaturist who left a strong imprint on his protégé’s style. Peter’s other interest was the army; he had been a volunteer drummer boy in a Bern company of grenadiers at the age of ten.

Peter’s father was a restless man. Thus when Captain Rudolph von May, an officer in De Meuron’s Regiment, visited Bern to recruit settlers on behalf of Lord Selkirk [Douglas*] for the Red River settlement (Man.) and described the colony’s agricultural prospects in fabulous terms, he was seduced. On 30 May 1821 he and his family left Dordrecht, Netherlands, with a contingent of more than 160 emigrants, mostly Swiss, aboard the Lord Wellington, bound for York Factory (Man.) on Hudson Bay.

The passage was difficult. En route the Lord Wellington met up with the Hudson’s Bay Company ships Prince of Wales and Eddystone and hms Hecla and Fury of Commander William Edward Parry*’s expedition in search of the northwest passage. Fifteen-year-old Peter sketched the ships, their dramatic encounters with icebergs, and the Inuit who came to trade with them. The party arrived at York Factory on 17 August. Shortly after, having to leave behind a large part of their supplies and belongings for want of boats, the Swiss set out on the gruelling, dangerous trip via Norway House to Fort Douglas (Winnipeg), the seat of the colony’s government, which was reached in November just before freeze-up. On the way Rindisbacher depicted HBC posts, indigenous people, and the party’s struggles over portages and up rivers. At Fort Douglas the exhausted Swiss learned that no preparations had been made for their reception, and that they would have to survive the winter on their meagre supplies and what they could forage. At the end of the winter Governor George Simpson* described their situation as “the most distressing scene of starvation that can well be conceived.”

In 1822 Pierre Rindisbacher built a house and began to farm. Peter supplemented the family income with earnings as a clerk at the HBC store in Fort Garry and from the sale of paintings. From 1823 James Hargrave*, a company clerk there, received orders for him from traders and officials delighted with his colourful and accurate depiction of life in the northwest, which they would keep as souvenirs or send home to relatives. Peter built up a repertoire of popular subjects; the original works were done in pen-and-ink, and from them copies were traced and finished in water-colour. In November 1824 George Barnston* at York Factory requested of Hargrave a number of works on Plains First Nations and the buffalo, “in which I think the young lad excells.” Submitting another order in 1826, he told Hargrave to let Rindisbacher “put his own price on the Drawings for he is a conscientious lad, I believe.”

In 1823 the interim governor of Assiniboia, Andrew H. Bulger*, had commissioned from young Rindisbacher a series of six water-colours depicting Bulger travelling by various conveyances and meeting with First Nations delegations. Robert Parker Pelly, Bulger’s successor, saw copies of the series and ordered a set, which he took with him to England in 1825. There he had oil copies made, depicting himself in Bulger’s place; from them coloured lithographs were produced and sold as sets in Britain, where John Franklin*’s expeditions were creating a market for them, and in the northwest, where “Pelly’s picture books” also sold well. Rindisbacher received neither credit for his originals nor remuneration from the sales. Similarly, the Reverend John West*, Anglican missionary at the Red River settlement, took six views to London and had them published as lithographs in 1825 or 1826; the lithographs credited West rather than Rindisbacher as the artist.

The young painter’s subjects included the Métis, company officials, and settlement life, but Rindisbacher was especially inspired by (and commissioned to paint) the exotic, colourful, and dramatic life of the area’s indigenous people. Bulger allegedly arranged a winter expedition to give him the opportunity to sketch a buffalo hunt. Only a few paintings, however, document the increasingly desperate plight of Rindisbacher’s own people. For the most part artisans, they were totally unfit to face the privations of a farming life at Red River. Man-made and natural disasters mocked their clumsy efforts to eke out a living. They began trickling south. In the spring of 1826 a devastating flood combined with an infestation of grub-worms discouraged the remaining die-hards, among them Pierre Rindisbacher. With his family and other Swiss settlers he left Red River on 11 July 1826 and settled at a place called Gratiot’s Grove (near Darlington, Wis.).

Peter continued to paint scenes of indigenous life, adding to his repertoire, but he also expanded his range of subjects to include miniature portraits of friends and local citizens. He visited St Louis in June 1829, and then travelled to Prairie du Chien (Wis.) to record a treaty-making ceremony and to do studies of the Sauk and Fox peoples. By year’s end he was living in St Louis, making miniatures in pencil, crayon, and water-colour. He had never lost his interest in the military life, and both in the Red River settlement and on the American prairies he was constantly in the company of soldiers; in St Louis he became a volunteer in the St Louis Grays. Army officers, through their contacts with the American social élite, brought their young painter friend to the notice of the buying public. In local newspapers the officers vaunted him as possessing “a genius as fruitful, and an imagination as vivid as the scenes amongst which he has dwelt” and asserted that “these will enable him, in cultivating his fine talents, to throw aside the threadbare subjects of the schools, and give to the world themes as fresh as the soil upon which he was bred; – glowing as the newness of nature; and picturesque as a combination of bold scenery, with bolder man and manners, will afford.” His friends sent scenes to the American Turf Register and Sporting Magazine, which published them in its pages. But the promise of success was cut short in 1834 when Rindisbacher died, possibly of cholera, at the age of 28. He seems to have been married and to have had two children.

Peter Rindisbacher’s success in his own time was based on the novelty of his subjects, the accuracy with which he depicted them, and the engaging quality of his style. Earlier paintings are naïve in execution, but his later Red River work is painted in clear harmonious colours and his subjects, spaced out in a tableau and bathed in a quiet, luminous light, have a serene quality. They remain somewhat wooden, however, and it was not until after 1826 that, through the use of sweeping lines, a more sombre restricted palette, and an almost metallic crispness of execution, he fully captured the spirit of his subjects. Constant improvement in his rendering of muscle structure may reflect his father’s knowledge of anatomy; it certainly reflects the development of his style. As an admirer observed in December 1829, “There is a living and moving effect in the swell and contraction he gives to the muscular appearance of his figures, that evinces much observation, judgement, and skill.”

Largely unknown until the 1940s, Peter Rindisbacher has come to occupy an important place in the history of Canadian art. Although he was of European origin, his youth and lack of formal training enabled him to develop a style rooted in the land of his adoption. He was the first resident professional artist west of the Great Lakes and superior in draftsmanship and feeling for his subjects to his closest American contemporary, the better-known George Catlin. He ranks among that group of celebrated artists of the west, including Catlin, John Mix Stanley, and Paul Kane*, whose principal interest was the recording of indigenous life. Rindisbacher’s close observation of detail combined with his growing ability to capture the spirit of his subjects and their land make him a valuable witness to his times and place, to be appreciated as much by historians, anthropologists, and geographers for the informational value of his work as by connoisseurs of art for the distinctive, evolving, and authentic quality of his paintings.

Through the promotional efforts of his fellow officers, the newly found popularity of Peter Rindisbacher lasted for a few years after his death. His works were published, usually by lithographic techniques, in J. O. Lewis, Aboriginal port folio: a collection of portraits of the most celebrated chiefs of the North American Indians (Philadelphia, 1835–36); T. L. McKenney and James Hall, History of the Indian tribes of North America with biographical sketches and anecdotes of the principal chiefs (3v., Philadelphia, 1836–44); Augustus Murray, Travels in North America during 1834, 1835, & 1836 (London, 1839); and American Turf Register and Sporting Magazine (Baltimore), 11 (1840): 495–96. From 1933, when historian Grace Lee Nute began rekindling interest in Rindisbacher, reproductions of his work have been used to illustrate a good many publications on Canadian and American art, on the Arctic and the West, as well as on indigenous people.

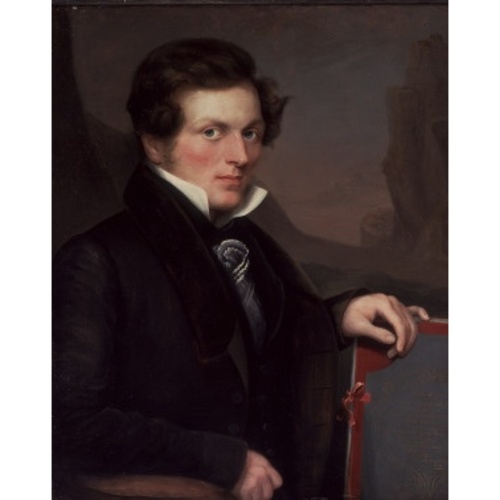

E. H. Bovay, Le Canada et les Suisses, 1604–1974 (Fribourg, Switzerland, 1976), lists 187 works by Rindisbacher and names the last known holder of each. In Canada, his works are held mainly at the PAC, the Glenbow-Alberta Institute, Calgary, and the PAM. A self-portrait by Rindisbacher painted in 1833–34 is reproduced in Bovay and in A. M. Josephy, The artist was a young man: the life story of Peter Rindisbacher (Fort Worth, Tex., 1970), which has a complete bibliography on Rindisbacher.

Lauperswil Registry Office (Lauperswil, Switzerland), Reg. of baptisms for the commune of Lauperswil, 1806. J. R. Harper, Painting in Canada, a history (Toronto and Quebec, 1966). F. [J.] Lindegger, Bruder des roten Mannes; das abenteuerliche leben und einmalige Werk des Indianermalers Peter Rindisbacher (1806–1834) (Aare, Switzerland, 1983). Barry Lord, The history of painting in Canada: toward a people’s art (Toronto, 1974). Karl Meuli, “Scythia Vergiliana: ethnographisches, archäologisches und mythologisches zu Vergils Georgica,” Beiträge zur Volkskunde (Basel, Switzerland, 1960), 140–75. Painters in a new land: from Annapolis Royal to the Klondike, ed. Michael Bell (Toronto, 1973). F. J. Lindegger, “Wie der Eggiwiler Peter Rindisbacher zum Indianermaler wurde,” Berner Nachrichten (Bern, Switzerland), 24, 29 Aug. 1978. J. F. McDermott, “Further notes on Peter Rindisbacher,” Art Quarterly (Detroit), 26 (1963): 73–76.

Revisions based on:

M. A. MacLeod et al., “Peter Rindisbacher: Red River artist,” Beaver, outfit 276 (Dec. 1945): 30–36.

Cite This Article

In collaboration with J. Russell Harper, “RINDISBACHER, PETER,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 6, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 13, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/rindisbacher_peter_6E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/rindisbacher_peter_6E.html |

| Author of Article: | In collaboration with J. Russell Harper |

| Title of Article: | RINDISBACHER, PETER |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 6 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1987 |

| Year of revision: | 2020 |

| Access Date: | February 13, 2026 |