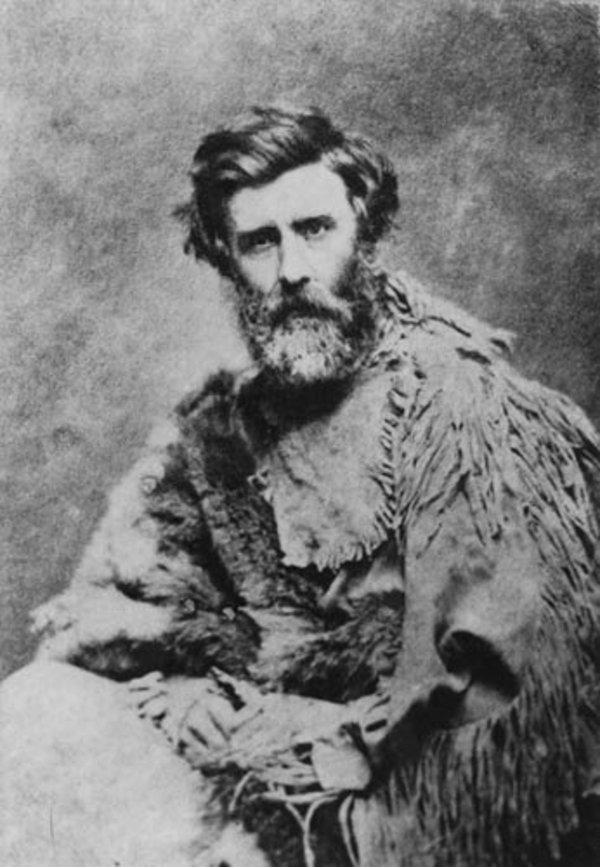

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

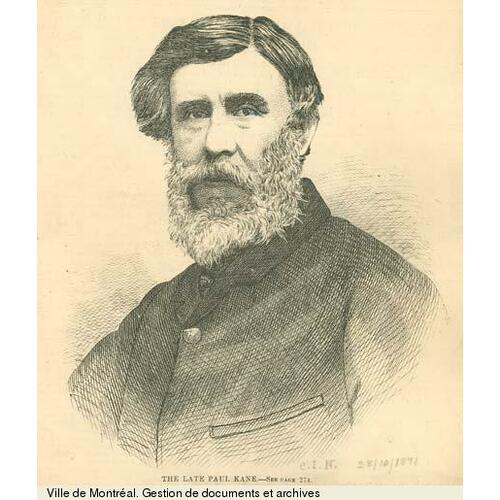

KANE, PAUL (his name is spelled Kean on his baptismal certificate), artist; b. 3 Sept. 1810, probably at Mallow, County Cork, Ireland; d. 20 Feb. 1871 at Toronto, Ont.

Paul Kane was the fifth of eight children born to Michael Kane and Frances Loach. Michael Kane was a native of Preston, Lancashire, England, and served in Captain G. W. Dixon’s troop of the Royal Horse Artillery from 1793 to 1801, when he was discharged with the rank of corporal. He had evidently been stationed in Ireland, where he married prior to his discharge. In 1805 he was living in Fermoy, County Cork, but some of his children were born in Mallow. It was repeatedly asserted by Paul Kane and his friends that he was a native of Toronto, but there can be no doubt that he was born in Ireland. About 1819 he immigrated with his parents to York (Toronto), where his father became a wine and spirits merchant.

Paul Kane is supposed to have been a pupil at the Home District grammar school at York though evidence is lacking. Thomas Drury (Drewery), a local painter and the art teacher at Upper Canada College, gave him painting lessons about 1830. When Kane decided to become a professional painter he followed a common practice among North American artists and worked briefly as a sign painter at York. Later he was a decorative painter of furniture in Wilson S. Conger’s furniture factory, also at York.

In 1833 he met James Bowman, an American artist then at York, who persuaded him that study in Italy was necessary for an artist aspiring to be competent and professional. However, Kane did not go overseas immediately. He lived in Cobourg from 1834 to 1836, working as a decorative painter in F. S. Clench’s furniture factory and painting portraits. His style in these portraits varied greatly. Some, like those of Mrs F. S. Clench and Mrs William Weller (Mercy Willcox), are primitive in approach but have a direct appeal and a warm colouring that make them attractive.

In 1836 Kane went to Detroit, where Bowman was then living; they had intended to go to Italy with Samuel Bell Waugh, an American portraitist who had worked briefly in Toronto. Bowman, however, had married recently, and the trip was again postponed. Instead, Kane remained in the United States and painted portraits for the next five years in Detroit, St Louis, Mobile, New Orleans, and other cities of central United States. None of these works were signed and only one canvas, depicting a ship owner or master with a Mississippi River boat in the background, has been traced to this period.

Kane’s passport documents his movements in the next two years. Leaving New Orleans by ship in June 1841, he arrived at Marseilles in September. A brief visit was made to Genoa where he saw his first gallery of old masters, and then he went to Rome for the winter. Along with many British and American art students in Rome he studied at the academies and copied paintings by Murillo, Andrea del Sarto, and Raphael. In the spring of 1842 he and a Scottish artist friend, Hope James Stewart, hiked to Naples. Several authors have stated that Kane went on to North Africa and the Near East but his passport does not bear out this claim. He remained with Stewart in northern Italy from May to September. In Florence Kane sketched the Donatello sculpture on Or San Michele and copied Raphael’s “Pope Julius II” in the Palazzo degli Uffizi; in Venice he copied canvases in the Accademia delle Belle Arti. He went north that autumn, going by foot through the Great St Bernard Pass into Switzerland on his way to England. After spending about four days in Paris, he reached London in late October and stayed for the winter, living with an English artist, Stewart Watson.

While in London, Kane met the American artist George Catlin. Catlin was then exhibiting and also lecturing in northern England and at Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly, London, on his paintings of Indians from the American prairies and the foothills of the Rockies. In his book, Letters and notes on the manners, customs and conditions of the North American Indians (London and New York, 1841), published just before Kane’s arrival in London, Catlin predicts the early disappearance of the North American Indian because of his contacts with Europeans. Thus, he argues, it is the artist’s duty to record his features and customs for posterity, while this is still possible. Kane, obviously inspired by this argument, decided to do in Canada what Catlin had done in the United States. He left London early in 1843, went first to Mobile, Alabama, where he had earlier been a popular artist, and set up a portrait-painting studio in April 1843. After working to repay money he had borrowed for his passage back from Europe, he returned to Toronto in late 1844 or early 1845.

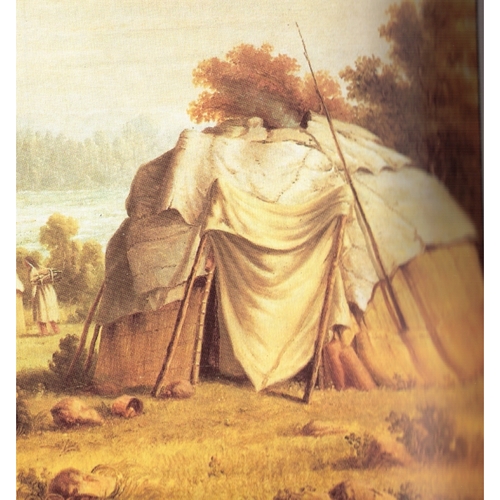

Kane’s own later writings record the next four years of his life until 1848. He left Toronto alone on 17 June 1845 with only his portfolio, sketching materials, and gun, intending to travel to the west coast. That summer he painted constantly in the Lake Huron and Lake Michigan region. In his account of the trip, Kane makes particular mention of his visits to the Saugeen Reserve on Lake Huron, to Sault Ste Marie, and to Fox River and Lake Winnebago, west of Lake Michigan. At Manitowaning on Manitoulin Island, he was present at an assembly of 2,000 natives from the whole area when the tribes received their annual presents. Later, at Mackinac Island, he attended an assembly where a payment for lands ceded to the United States government was made. Sketches were made among what Kane described as the Chippewas, Ojibwas, Ottawas, and Potawatomis, and among the Menominees.

A meeting with John Ballenden*, the Hudson’s Bay Company chief trader at Sault Ste Marie, changed Kane’s immediate plan to continue west beyond the Lake Michigan area. The trader pointed out the difficulties such a trip involved and suggested that he first request assistance from Sir George Simpson*, the superintendent of the HBC in North America. Following this advice, Kane returned to Toronto that autumn and visited Simpson in Montreal. Kane received permission to travel with the company’s fur brigades and was promised free lodging at company posts. That winter he remained in Toronto and painted canvases from the previous summer’s sketches. The finest of this group are his “Encampment among the islands of Lake Huron” and “Sault Ste Marie.”

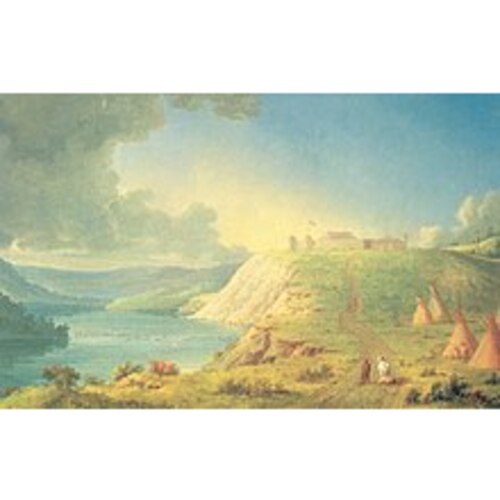

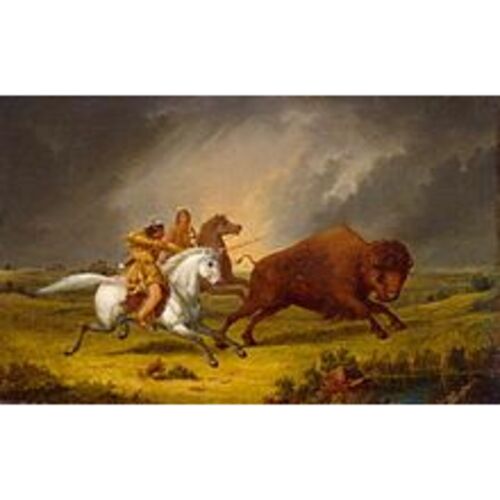

Kane’s second year of sketching began after he overtook the HBC spring fur-trade brigade at Fort William on 24 May 1846. He travelled westward with the fast moving canoes and sketched when they halted at portages. A brief stop at Fort Frances gave him the opportunity to meet Saulteux Indians. A series of sketches illustrating the annual Métis buffalo hunt and also Sioux was made during an excursion south from Upper Fort Garry. Continuing north with the brigade, he spent several weeks at Norway House as a guest of Donald Ross. He then turned westward with the brigade to follow the Saskatchewan River past Fort Carlton, where he sketched the Crees, to Fort Pitt. While riding overland from Fort Pitt to Fort Edmonton, he was accompanied by the Reverend Robert Terrill Rundle* and Chief Factor John Rowand*. His party crossed the mountains from Jasper House to the upper Columbia River, which they descended, stopping at Fort Colvile and at Walla Walla. On 8 Dec. 1846 they reached Fort Vancouver (now Vancouver, Washington), the principal HBC post west of the mountains, administered by Peter Skene Ogden* and James Douglas.

Kane made Fort Vancouver his principal base, and from it he journeyed to Oregon City, visited the Clackama Indians, and sketched in the Willamette River valley. On 25 March he left Fort Vancouver to explore the lower Columbia area. He sketched the erupting Mount St Helens, the last active volcano in North America, and was fascinated by the canoe burials on the Cowlitz River and by the various head deformation practices of the Indians farther north.

Kane continued to Fort Victoria and arrived at a time of particular activity. Fort Vancouver was to be abandoned by the HBC when the Oregon country was transferred to the United States, and Fort Victoria was being enlarged to replace it. Here he sketched intensively, at the fort, along the Vancouver Island coastline, and on the mainland down to Puget Sound, among the Haidas and other west coast tribes. Returning to Fort Vancouver on 20 June 1847, he stayed only ten days before beginning the journey back to Toronto.

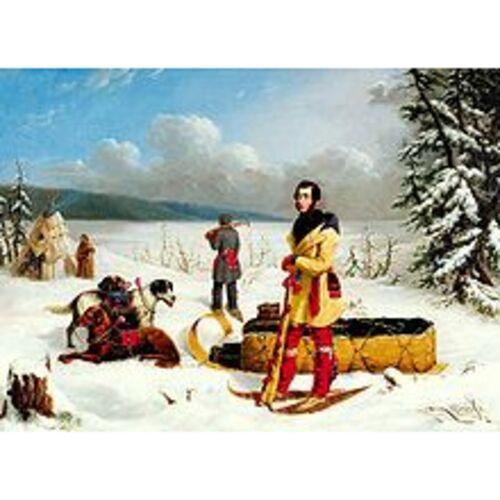

Along the way, Kane visited the Grand Coulee Lake region around Walla Walla and sketched among the Cayuse, Nez Percés, and other Plateau Indians. At Fort Colvile he was present at a Colville (Kane called them Chualpays) Indian scalp dance, and watched the Indians salmon fishing. The lateness of the season made crossing the mountains difficult and the small party of HBC employees accompanying Kane did not reach Fort Edmonton until December. This was Kane’s headquarters until the following summer, providing him with the opportunity to sketch the Indians of the western plains and visit Rocky Mountain House. The Crees especially attracted him and he witnessed their medicine pipe-stem dance and other ceremonials. He left Fort Edmonton on 25 May travelling eastwards with the fall fur-trade brigade led by John Edward Harriott*. At Norway House he joined some British army officers also travelling to Sault Ste Marie. Here he boarded a steamship and reached Toronto in October 1848, after an absence of two and a half years.

Kane was but one of a group of painters who were discovering the emerging west, and several other artists visited the Columbia River during the 1840s. Henry James Warre, a British army officer, sketched there and at Fort Victoria in 1845. John Mix Stanley, whom Kane had probably met at Detroit in 1836, did considerable work among the Columbia River Indians in 1847 and painted some subjects identical to those chosen by Kane; Kane missed meeting him by only a few days. Father Pierre-Jean De Smet, a Jesuit, also sketched the Columbia Indians in 1845. Finally, in 1855 Gustavus Sohon worked among the Flatheads and other tribes east of Walla Walla, sketching some of the same individuals Kane had previously portrayed. Yet, although Kane is not the only artist to document the whole region artistically, he must be considered the most important because of the excellence of his work and the extensive and thorough treatment he gave his subject-matter.

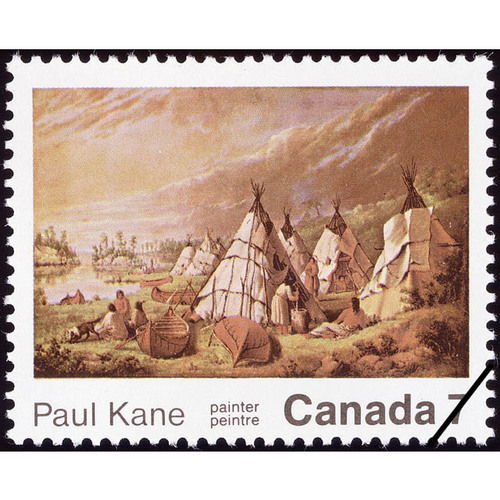

Many of Kane’s sketches are particularly important for the study of 19th-century Canada. His portrayal of the Métis buffalo hunt is detailed and his record of the HBC forts is of tremendous interest. Two of the Columbia River sketches are unique: that of the Whitman Mission, which was destroyed at the time of the massacre of 1847, and that of the church of Saint-Paul-de-Wallamette in the Willamette valley, the first brick building on the Pacific coast.

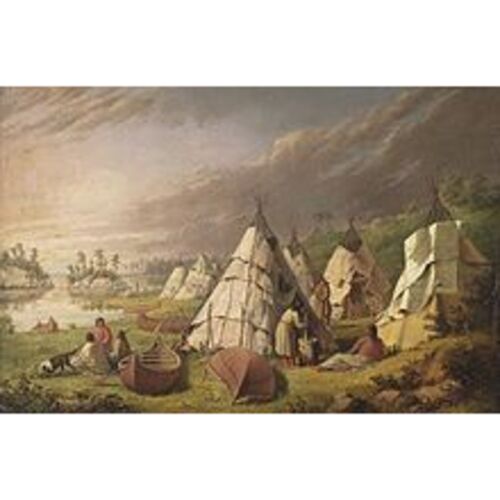

Ethnologists find a wealth of information in his portrayal of the life and customs of the native peoples. Of particular significance are sketches from Victoria of women spinning and weaving, and of Indian artifacts. Equally important are the sketches of fishing and of the scalp dance rituals on the upper Columbia, and of the rituals of the militarist society of the Indians of the plains. No other pictorial record of the early Canadian northwest even approaches the wealth or magnitude of that made by Kane.

Kane returned to the northwest in the spring of 1849, but only went as far as the Red River Settlement. On this occasion he guided Sir Edward Poore, a young officer, and two of his friends who were in search of adventure in the west. The trip was made almost entirely in American territory by way of the Mississippi River and Kane does not mention having done any sketching.

For the remainder of his life Kane was a painter in Toronto. He had made more than 700 sketches from 1845 to 1848, some carefully executed and others hasty pencil notes. They now became virtually the entire subject-matter for his canvases and he occasionally painted several versions of the same subject. He had already, in the winter of 1848, begun painting these canvases, including 14 destined for Sir George Simpson. The canvases, in oil, are stolid and dull compared to the brilliant and fresh water-colour and oil studies completed in the field. He was afraid, it would seem, to follow his own sketches literally; in them the colours are almost impressionistic. He later often substituted dull grey backgrounds for his portraits.

Kane has been criticized for the European characteristics found in these paintings. In some, for example, the clear Canadian skies of the sketches have been overlaid with European cloud formations. Other instances of this European influence may be simply the consequence of particular circumstances: trimmed greenswards may have resulted from the lack of detail in small spot sketches. However, it has been shown that a few compositions are actually based on European prototypes. Occasionally, the horses in his canvases have classical lines, modelled after Italian engravings. In his “Assiniboine hunting buffalo,” Kane reinterpreted an Italian engraving of 1816 of two Romans hunting a bull. “The death of Big Snake” is inspired by a European romantic artist who painted like Théodore Géricault; it is an entirely imaginary work painted after Kane heard an incorrect report of the death of Big Snake [Omoxesisixany]. The Indian actually died in 1858, several years after the execution of the painting. This painting was lithographed in Toronto under the supervision of the artist in the mid-1850s and is said to be the first coloured lithograph published in that city.

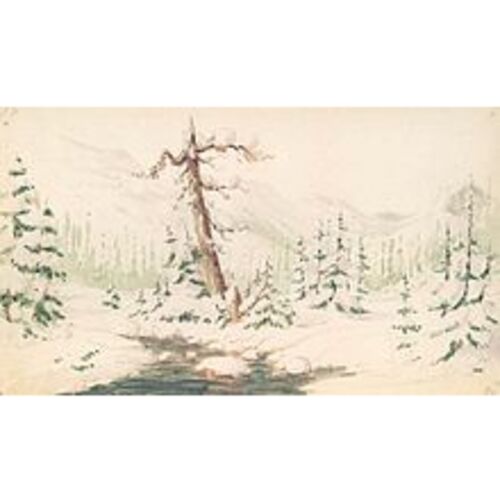

These “created” compositions are, however, exceptions to the rule. Most canvases were painted either from individual studies or from several studies which he combined onto a single canvas. His “Winter travelling in dog sleds” is based on a pencil sketch of the scene and on water colour studies of a sleigh, of two harnessed dogs, and of trees covered with snow.

Kane stressed that he strove for accuracy in recording his subject-matter but this assertion is only partly true for his canvases. His Indian portraits are often embellished with features such as hair ornaments and elaborate robes which do not appear in the field sketches but which produce a more exotic effect. Nor was any real attempt made to relate the artifacts reproduced on the canvas to the tribal designation of the sitter. The result is often confusing to the ethnologist.

Today’s public will find many of Kane’s field sketches his most attractive works. They were executed simply and precisely, their colours are fresh, and they make an immediate impact on the viewer. On the other hand, the canvases based on the sketches, which were intended for gallery display and on which Kane felt that his reputation would rest, lack the brilliance of the colour of the more intimate sketches; though many are impressive works, they are sometimes laboured, and often include too many embellishments.

Opportunities for the public exhibition of paintings in the Ontario of Kane’s day were limited. His early canvases were shown at the exhibitions of the Society of Artists and Amateurs in York in 1834 and of the Toronto Society of Artists in 1847. A two-week exhibition of 240 sketches by Kane and of the Indian artifacts he had collected during his trips was held at the Toronto City Hall in November 1848, giving Canadian residents their first real opportunity to view the northwest. Newspaper publicity was extensive both on the subject-matter and on the value of the sketches to aspiring young artists for study purposes. Kane probably first met George William Allan*, a leading Canadian financier and politician who was to be his future patron, at this exhibition. The next year the governor general, Lord Elgin [James Bruce*], and his wife called at his studio to see his western sketches.

Between 1851 and 1857 Kane exhibited his western paintings and won awards at the annual Upper Canada Agricultural Society exhibitions held in various centres in Canada West. He was acclaimed a celebrity when he appeared at one of these in person. The excellent reviews of the canvases the Canadian government sent to the Paris exposition of 1855 reputedly much cheered the artist.

Until the 1850s only a portrait painter could hope to earn a reasonable income from artistic production in Canada. In 1851, Kane had applied to the Canadian government for monetary assistance to paint the canvases from his sketches, basing his claim on the national importance of his work. The government gave him a grant of £500 on condition that he deliver 12 canvases to the Library of Parliament, and several paintings were commissioned by private individuals. His most important work with his western sketches constitutes a cycle of 100 canvases painted for Allan for $20,000, and completed by March 1856. Kane intended illustrating the Canadian native peoples, their customs, and the scenery of the country in which they lived by this group of paintings. Catlin and Stanley had painted similar cycles, which they sold to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington as a permanent record of the American Indians. Similarly, Kane would undoubtedly have preferred to have had the government buy his works, and he wished to see the group preserved for the people of Canada.

As early as October 1848 Kane planned a book describing his trips of 1845–48, based on the notes and diaries he kept en route. In the 1850s he began writing Wanderings of an artist among the Indians of North America. Although some chapters were delivered before the Canadian Institute (later the Royal Canadian Institute) in 1855, published in its annual proceedings, and republished in the Daily Colonist, the publication of the complete volume was long delayed. Finally, a visit by Kane to England in 1858 and, simultaneously, pressure from influential persons, presumably Simpson and his associates of the HBC, resulted in the publication of the volume in 1859. A pirated French edition appeared in 1861, and, in 1863, a Danish edition. When it was first published, the volume contained coloured lithographs and woodcut illustrations based on the sketches and canvases in the Allan collection. A German edition with newly prepared lithographs and woodcuts, and genre scenes by another artist, was published in several parts beginning in 1860 and as a complete work in 1862. Kane also intended publishing a book consisting of plates depicting the west. He prepared a portion of the text for such a volume but it was never published. Kane dedicated his Wanderings to George Allan. Simpson took umbrage at this and ordered the HBC staff neither to receive Kane at their posts nor to assist him in any way in the future. It was apparently for this reason that Kane abandoned a proposed sketching trip to Labrador in 1861.

Kane exerted a major influence on many people. Sir Daniel Wilson*, professor at the University of Toronto, became a close friend and relied heavily on Kane’s information on the plains and Pacific coast Indians for his Prehistoric man, searches into the origin of civilisation in the old and the new world, the first major anthropological work written in Canada. Among Kane’s later associates were men like Allan, Wilson, and Frederick A. Verner. The last, in emulation of Kane, painted the Indians and buffalo of the prairies. Lucius Richard O’Brien* was also influenced in his early years as an artist by Kane.

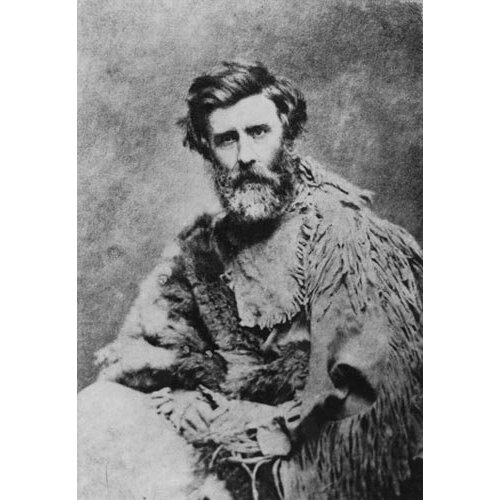

Kane had married Harriet Clench of Cobourg, the daughter of his former employer, in 1853, and they had several children. After 1862 they lived in a house which they built on Wellesley Street in Toronto. The artist evidently maintained a studio on King Street until he was forced to retire because of his increasing blindness, which began to be apparent in 1858. He kept somewhat aloof in later life, possibly embittered by his bad sight (which he blamed on the glare from the snow in the Alps during his 1842 trip and also in the west), and by the lack of continuing interest in his work on the part of the general public.

He died suddenly at his Toronto home shortly after returning from his daily walk.

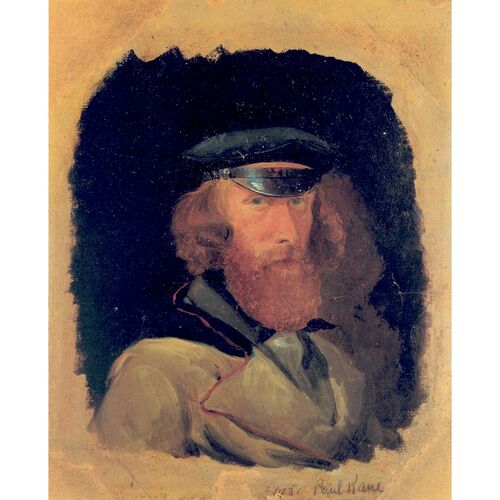

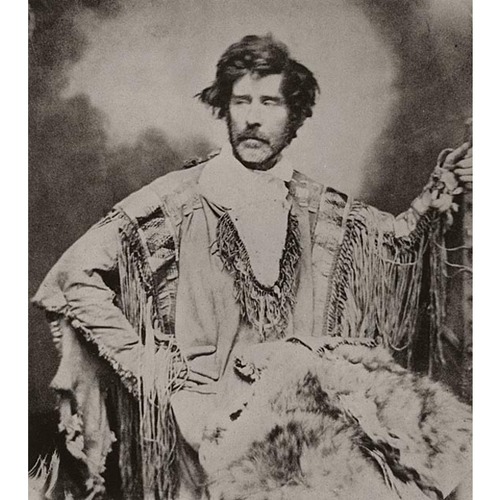

[The great bulk of known sketches and paintings by Paul Kane is divided between three depositories. Of the 12 canvases he delivered to the Library of Parliament, 11 are now in the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa. The cycle of 100 paintings completed in 1856 was purchased by Sir Edmund Boyd Osler* in 1903, and presented to the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, where they are now located. Most of the sketches made during the field trips are in the Royal Ontario Museum and with the Stark Foundation in Orange, Texas. Kane’s collection of Indian artifacts was donated by the Allan family to the Manitoba Museum of Science and History in Winnipeg. A catalogue raisonné of Kane’s sketches and paintings is in Paul Kane’s frontier; including Wanderings of an artist among the Indians of North America by Paul Kane, ed. J. R. Harper (Toronto, 1971). Frederick A. Verner produced three portraits of Kane. The most important one is now in the collection of the Royal Ontario Museum. An early self-portrait is in the Weir collection in London, Ont. Another, painted during his first western tour, is in the Stark Foundation collection.

Paul Kane, “The Chinook Indians,” Canadian Journal, new ser., II (1857), 11–30; “The Chinook Indians,” Daily Colonist (Toronto), 6, 7, 8, 9 Aug. 1855; “Incidents of travel on the North-West coast, Vancouver’s Island, Oregon, etc. The Chinook Indians,” Canadian Journal, III (1854–55), 273–79; “Notes of a sojourn among the half-breeds, Hudson’s Bay Company’s territory, Red River,” Canadian Journal, new ser., I (1856), 128–38; “Notes of travel among the Walla-Walla Indians,” Canadian Journal, new ser., I (1856), 417–24; Wanderings of an artist among the Indians of North America from Canada to Vancouver’s Island and Oregon through the Hudson’s Bay Company’s territory and back again (London, 1859); republished with intro. and notes by L. J. Burpee (Master-works of Canadian authors, ed. J. W. Garvin, VII, Toronto, 1925; repub. with intro. by J. G. MacGregor, Edmonton, 1968). The 1859 edition is included in Paul Kane’s frontier. . . . The Wanderings has also been translated into French, German, and Danish: Les Indiens de la baie d’Hudson, promenades d’un artiste parmi les Indiens de l’Amérique du Nord . . . , trans. Édouard Delessert (Paris, 1861); Wanderungen eines Künstlers unter den Indianern Nordamerika’s . . . , trans. Luise Hauthal (Leipzig, 1862); En Kunstners Vandringer blandt Indianerne i Nordamerika . . . , trans. J. K. (Copenhagen, 1863).

Kane’s writings were reviewed in: Charles Lavollée, “Un artiste chez les Peaux-Rouges,” Revue des deux mondes (Paris), XXII (1859), 963–86. Daniel Wilson, “Wanderings of an artist,” Canadian Journal, new ser., IV (1859), 186–94. Athenaeum (London), 2 July 1859, 14–15. Kane’s work is mentioned in the following catalogues: Catalogue of the first exhibition of the Society of Artists and Amateurs of Toronto (Toronto, 1834). Catalogue of sketches and paintings by Paul Kane (Winnipeg, 1922). Catalogue, pictures of Indians and Indian life by Paul Kane (property of E. B. Osler, n.p., [1904]). Paul Kane, Catalogue of sketches of Indians, chiefs, landscapes, dances, costumes, etc. (Toronto, 1848). National Gallery of Canada, Catalogue of paintings and sculpture, ed. R. H. Hubbard et al. (4v., Ottawa, 1959–65), III: The Canadian school, 151–56.

Art Gallery of Ontario (Toronto), Challener papers, notes on Paul Kane. Church Missionary Society Archives (London), Journal of the Reverend J. Hunter. HBC Arch. D.4/54, D.4/67, D.5/15, D.5/24. British Colonist (Toronto), 14 Nov. 1848. Canadian Agriculturist (Toronto), III (1851), 228; IV (1852), 292–93. Morgan, Sketches of celebrated Canadians, 731–33. Oregon Spectator (Oregon City), 11 Feb. 1847. “Paul Kane,” Anglo-American Magazine (Toronto), VI (May 1855), 401–6. Valley of the Trent (Guillet), lvii.

W. G. Colgate, Canadian art, its origin and development (Toronto, 1943). Davin, Irishman in Canada, 611–17. J. R. Harper, Painting in Canada, a history (Toronto, 1966). W. H. G. Kingston, Western wanderings or, a pleasure tour in the Canadas (2v., London, 1856), II, 39, 42–47. A. H. Robson, Paul Kane (Toronto, 1938). Daniel Wilson, Prehistoric man, searches into the origin of civilisation in the old and the new world (2v., Cambridge and London, 1862).

D. I. Bushnell Jr, Sketches by Paul Kane in the Indian country, 1845–1848 (Smithsonian Misc. Coll., XCIX, Washington, 1940). W. G. Colgate, “An early portrait by Paul Kane,” Ont. Hist., XL (1948), 23–25. J. R. Harper, “Ontario painters, 1846–1867,” National Gallery of Canada, Bull. (Ottawa), I (1963), 16–31. K. E. Kidd, “Notes on scattered works of Paul Kane,” Royal Ontario Museum, Art and archaeology division, Annual, 1962, 64–73; “Paul Kane – a sheaf of sketches,” Canadian Art (Ottawa), VIII (1950–51), 166–67; “Paul Kane, painter of Indians,” Royal Ontario Museum of Archaeology, Bull., 23 (Toronto, 1955), 9–13; “The wanderings of Kane,” Beaver, outfit 277 (December 1946), 3–9. Daniel Wilson, “Paul Kane, the Canadian artist,” Canadian Journal, new ser., XIII (1871–73), 66–72. Kathleen Wood, “Paul Kane sketches,” Rotunda (Toronto), II (1969), 4–15. j.r.h.]

Cite This Article

J. Russell Harper, “KANE (Kean), PAUL,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 19, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/kane_paul_10E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/kane_paul_10E.html |

| Author of Article: | J. Russell Harper |

| Title of Article: | KANE (Kean), PAUL |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1972 |

| Year of revision: | 1972 |

| Access Date: | February 19, 2026 |