Source: Link

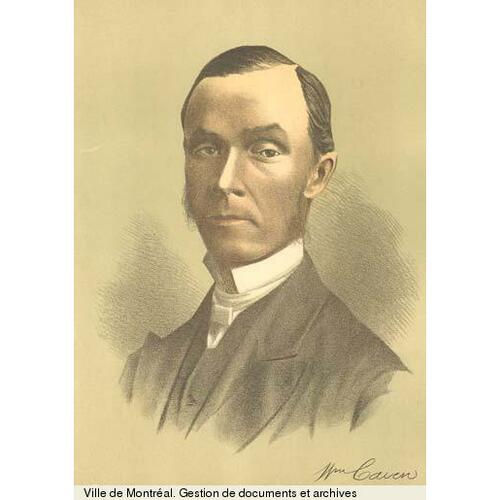

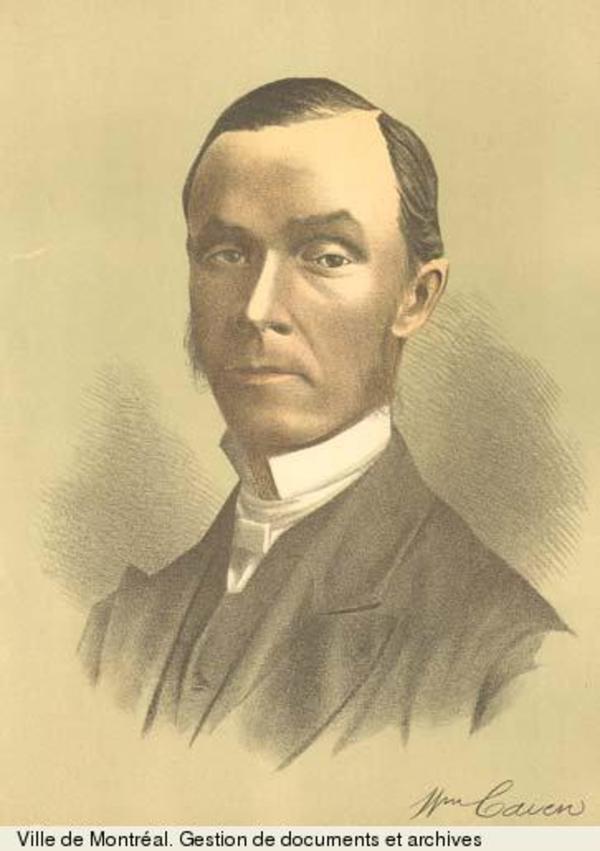

CAVEN, WILLIAM, Presbyterian minister, educator, and theologian; b. 26 Dec. 1830 in Kirkcolm, Scotland, son of John Caven and Mary Milroy; m. July 1856 Margaret Goldie, daughter of botanist John Goldie, and they had three sons and three daughters; d. 1 Dec. 1904 in Toronto.

William Caven was born into a Scottish Secessionist family with strong Covenanting roots. Among his ancestors were men who signed the Solemn League and Covenant and whose names appeared on the roll of the Wigton martyrs. Liberal principles in politics and voluntaryism in religion were characteristics of this tradition. William was educated at home in Scotland by his father. In 1847 the family moved to Upper Canada, to Dumfries Township, near Galt (Cambridge). John Caven taught in Ayr and later served as superintendent of schools in Waterloo County. William taught school for a few months in Blandford Township before beginning studies for the ministry with William Proudfoot* and Alexander Mackenzie at the United Presbyterian Seminary in London, Upper Canada, in 1847. In 1852 Caven was licensed by the Presbytery of Flamborough and accepted a call to the two-point charge of St Marys and Downie. He was ordained on 7 October that year.

Caven would make significant contributions to church and nation in three areas: as an educator, as an ecclesiastical statesman, and as a leader of public campaigns for the preservation of Protestant moral principles in the legislation of various levels of government. In 1866 he was offered and accepted the chair of exegetical theology and apologetics at Knox College, Toronto, where he had been lecturing in exegetical theology since 1864, following the resignation of George Paxton Young*. By 1869 Caven was also teaching biblical criticism. Towards the end of his life, in 1896, a separate chair of Old Testament literature would be created, and Caven would be left with the chair of New Testament literature and exegesis. Upon the retirement of Principal Michael Willis* in 1870, Caven was named chairman of the senate of Knox College. Three years later he was appointed principal; he would hold the post till his death. Under his leadership the college raised some $120,000 for new buildings on Spadina Avenue, which opened in 1875. As an educator he was active outside the college as well, and in 1887 he succeeded Goldwin Smith as president of the Ontario Teachers’ Association. Queen’s College, Kingston, had conferred an honorary dd upon him in 1875 and Princeton Theological Seminary in New Jersey did the same in 1896. Also in 1896 he received an lld from the University of Toronto.

Caven guided Knox College during a time of intense theological ferment and taught biblical studies in years marked by heated debate in all Protestant theological colleges over the nature and authority of Scripture. His position in the religious controversies of the late 19th century was that of a moderate conservative. Though open to new insights gained by thorough investigation of the Bible, he insisted that the burden of proof rested on those advocating change in doctrine or practice. “A well-balanced mind,” Caven wrote in the Knox College Monthly in 1891, “is at once conservative and progressive; – conservative of everything good which has come down to us, while it seeks by careful investigation to enlarge the boundaries of ascertained truth and to purge away errors and mistakes.” He was confident that the central doctrines of evangelical Protestantism concerning God and humanity – the Trinity, the person of Christ, original sin, the atonement, and justification – were clearly evident in Scripture and were sufficient foundations for any task of theological reconstruction that might face the church. “The Church started out with a revelation of truth,” he told Donaldson Grant in an interview in 1902, “which could not be disproved and which no change could destroy. The belief in one God, in one Saviour, in one Holy Spirit, and in one way of salvation from the guilt and power of sin, may be more clearly apprehended and more exactly stated, but no radical change can be made in the content of that belief, based as it is on divine revelation.”

In the various proceedings of the heresy trial of Daniel James Macdonnell* from 1875 to 1877, Caven supported Macdonnell’s right to raise questions about the doctrinal standards of the Presbyterian Church in Canada. Caven’s view of the limits of that questioning, however, was clearly stated in articles in 1879 and 1882 in the Catholic Presbyterian, a journal serving the Pan-Presbyterian Alliance, an international council of Presbyterian churches. Whatever developments there might be in the construction of doctrine, he argued, these would have to remain steadfastly biblical, take due regard of the church’s doctrinal attainments, and contribute to “the growing spiritual life and holiness of the Church.”

Caven’s views were promulgated through many articles, reviews, sermons, and addresses published or reported in the religious and secular press or issued in pamphlet form. The international theological journal with which he was most closely associated was the Presbyterian Review, edited by Archibald Alexander Hodge of Princeton Theological Seminary and Charles Augustus Briggs of Union Theological Seminary in New York City. Caven became an associate editor in 1885 and regularly contributed book reviews and reports on Canadian affairs. In 1890, on the eve of the heresy trial that led to Briggs’s suspension from the Presbyterian ministry in 1893 and broke the official connection of Union seminary with Presbyterianism, the journal became the Presbyterian and Reformed Review. Caven remained on the editorial board and continued to publish in the journal until 1903.

In addition to his duties at Knox College, Cavenwas active in the affairs of the University of Toronto. For almost 20 years following the affiliation of Knox with the university in 1885, he served on the university’s senate. He played a crucial role in the negotiations that resulted in more adequate government funding for University College and in the federation of the University of Toronto in 1887 [see Sir Daniel Wilson*]. Caven had initially opposed the appeal for increased funding, but came to see the value of a single university with several colleges. His position was made public in two lengthy letters to the Globe in December 1883, later published in a pamphlet. A single university, he argued, would bring together various classes and creeds and make a significant contribution to the elimination of sectionalism, partyism, and denominationalism. State control should be coextensive with state support, eliminating any alliances between individual churches and the civil government. This position was consistent with the voluntaryism of Caven’s Secessionist background.

Caven was recognized as an adviser of Sir Oliver Mowat, premier of Ontario from 1872 to 1896, and of George William Ross* during his years as minister of education in Ontario from 1883 to 1899 and as premier from 1899 to 1905. Both Caven and Mowat belonged to St James Square Presbyterian Church. They were elected elders by the congregation in 1870 but declined to serve because of the burdens of their respective offices. Both were officers of the Evangelical Alliance, Caven serving for some years as vice-president of the Toronto branch. Caven gave the eulogy at Mowat’s public funeral. Premier Ross saw Caven as a “better judge of abstract problems than of men,” but acknowledged him to be a valued adviser. The two politicians recognized Caven as a key figure in keeping the Scottish and Irish Presbyterians in the Liberal camp.

Caven was a leader in the negotiations that led in 1875 to the unification of various Presbyterian bodies to form the Presbyterian Church in Canada [see John Cook*] as well as in the initial stages of the negotiations that would lead to church union in 1925. When the Cavens had immigrated in 1847, Presbyterians in British North America were organized into eight distinct bodies reflecting geographical and theological differences. A series of regional unions reduced the number to four by 1868. In 1870, in the wake of confederation and at the urging of prominent Presbyterian businessmen, negotiations for a single Presbyterian church in the dominion began in earnest. The following year the Canada Presbyterian Church (formed in 1861 by a union of the Free Church and the United Presbyterian Church in Canada in connection with the United Presbyterian Church in Scotland) added Caven and five others to its union committee. Their presence was intended to counteract the resistance to union from such Free Church partisans as the Reverend Lachlan McPherson of East Williams Township and the Reverend John Ross of Brucefield. Caven’s leadership in the cause of church union was acknowledged when he was elected moderator of the Canada Presbyterian Church for 1874–75 and invited to participate in the founding service of the Presbyterian Church in Canada at Montreal’s Victoria Hall on 15 June 1875 (he would serve as moderator of this body in 1892–93).

Presbyterians now constituted the largest Protestant denomination in Canada and were confident that their numerical strength, economic resources, and ecclesiastical vision were adequate to the challenge of expansion that faced them in the new dominion. Caven and others, notably George Monro Grant of Queen’s College, hoped for a broader union that would bring together all of the evangelical Protestant churches in Canada. From 1888 until his death in 1904, Caven chaired a series of committees on church union appointed by the Presbyterian General Assembly. In 1889 he was a key speaker at the Toronto Conference on Christian Unity, which brought together Presbyterians, Anglicans, and Methodists. These talks faltered as a result of the Anglican insistence on the historic episcopate.

In 1898 the Canadian Society of Christian Unity was founded under the presidency of Herbert Symonds*, an Anglican; George Grant served as its second president, and Caven as its third. Caven presented his General Assembly with a memorial from the society in 1902, asking that union be actively pursued. That same year the Methodist General Conference in Winnipeg issued an invitation to the Congregationalists and the Presbyterians to seek organic union. The Presbyterians again appointed Caven to convene their committee. The first joint meeting, led by his successor Robert Harvey Warden, took place in Knox’s Church, Toronto, from 20 to 22 Dec. 1904, just three weeks after Caven’s death. Caven had also played a leading role in the Pan-Presbyterian Alliance from its inception in 1877. He served as its president for the last four years of his life.

In a feature article in the first issue of the Westminster, an interdenominational magazine edited by Caven’s former pupil James Alexander Macdonald*, Caven summarized the principles that informed his advocacy of church union. There was nothing in Scripture, he argued, that sanctioned the divided state of the church. Admittedly, many of the current divisions resulted from conflicts over the purity of doctrine or the freedom of religion, but when the reasons for disunity disappeared, as Caven was sure they had among evangelical Protestants, union should be restored. He listed four conditions for reunion: affirmation of the great doctrines of the Christian faith, agreement on the constitution and administrative structures necessary to allow the church to pursue its mission, a free spiritual life that acknowledged the glory of God as its supreme aim, and mutual esteem and affection among the denominations. One of the reasons for Caven’s advocacy of church union was his belief that a united Protestantism would have a much more powerful influence on national righteousness than separate denominations.

Together with his work for church union, Caven was a spokesman for the Protestant moral reform causes of “equal rights,” sabbath observance, and temperance. Like his fellow clergyman Donald Harvey MacVicar, he played a major role in the opposition to the Jesuits’ Estates Act of 1888 [see Honoré Mercier*]. Caven’s objections to the Quebec bill restoring to the Jesuits a significant portion of the income from estates confiscated at the time of the conquest were fourfold. He saw the legislation as a violation of the trust under which the lands were given to the Quebec legislature; it disrupted the arrangement by which the revenues were devoted to higher education; it elevated the authority of Roman canon law over the law of the empire; and it recognized the right of the pope to interfere in Canadian civil affairs in a way that compromised true freedom. His opposition was based on the principle that churches must not receive public funds to aid them in their proper work, nor may they draw upon the public treasury with the excuse of doing work beneficial to the state.

Opposition to the act and to the federal government’s refusal to disallow it crystallized in ministerial associations and in the Evangelical Alliance. In Toronto protests culminated in the gathering of Canada’s first and only Anti-Jesuit Convention, on 11–12 June 1889. The meetings, chaired by Caven, led to the establishment of the Equal Rights Association to continue the agitation for disallowance. Caven was chosen as its president. Ensuing events led to a struggle between Caven, who saw the ERA as a principled pressure group, and D’Alton McCarthy*, who sought to turn the association into a Protestant political party. Caven’s views held sway until his resignation as president in December 1890. Some linked the ERA with the founding of the Protestant Protective Association, but Caven roundly condemned the latter organization for its intolerance and political aspirations. Throughout the controversy, Caven remained supportive of the educational policies of Oliver Mowat and George Ross with respect to the rights of Catholics in Ontario. Later, however, he actively opposed public support for Catholic schools in Manitoba.

Shortly after the “equal rights” agitation, Caven, a member of the Lord’s Day Alliance, became a leading spokesman in efforts to resist the introduction of Sunday streetcars in Toronto. From his appearance on the platform at a mass rally in December 1891 until Sunday cars were allowed in 1897, he was consistent in his opposition through ministerial associations and citizens’ committees, in the pulpit, on the platform, and in the press. It was not enough, he argued in a pamphlet published in 1897, to leave sabbath observance to the religious sentiment of the community. “A community has a common life, and the fundamental convictions of any community must at length necessarily influence and find expression in its laws.” Legislative protection of the rest and quiet of the Lord’s Day as a commemoration of creation and redemption was “surely necessary and right” in a Christian nation such as Canada. Caven’s minister at St James Square, Alfred Gandier, noted in an obituary in the Globe that he refused to use Sunday streetcars and walked two miles to church each week.

Another important moral cause that enjoyed Caven’s public support was the temperance movement. Caven was on the executive of the Ontario branch of the Dominion Alliance [see Francis Stephens Spence*] when in 1902 the Ross government introduced temperance legislation patterned on that in Manitoba. The Manitoba act had just survived a legal challenge in the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. Attached to the Ontario bill, however, was provision for a referendum to ascertain public support. Caven and the executive of the Dominion Alliance reluctantly accepted the referendum, recognizing that the legislation required significant public support if it was to be enforced. Caven took part in the campaign through platform and press, but the temperance activists were narrowly defeated. Writing in the Globe in 1904, Caven continued to urge the government to be true to its promises and abolish the bar, though he was satisfied with the proposed legislation that would permit the consumption of alcohol in private homes.

Caven’s death from pneumonia late in 1904 was mourned in editorials across Canada. As a churchman, he was remembered as one who steadfastly opposed any unreasonable innovation that threatened to destroy popular reverence. As a citizen, he was honoured as one who upheld the centrality of Protestant moral principles in the life of the nation.

An oil portrait of William Caven hangs in the library named in his honour at Knox College, Univ. of Toronto.

A number of Caven’s essays and letters to the press were published in pamphlet form: A vindication of doctrinal standards: with special reference to the standards of the Presbyterian Church (Toronto, 1875); The Scripture readings: a statement of the facts connected therewith . . . ([Toronto, 1886]), consisting of a letter by Caven and one by the Methodist clergyman Edward Hartley Dewart; Equal rights; the letters of the Rev. William Caven, d.d. ([Toronto, 1890]); The divine foundation of the Lord’s Day; an address ([Toronto, 1897]); and The testimony of Christ to the Old Testament, issued at Toronto sometime shortly after his death. A collection of his writings also appeared posthumously under the title Christ’s teaching concerning the last things and other papers (London and Toronto, 1908).

Noteworthy articles by Caven include: “Progress in theology . . . ,” Catholic Presbyterian (London and New York), 1 (January–June 1879): 401–11, and 8 (July–December 1882): 280; “College confederation in Ontario,” Presbyterian Rev. (New York and Edinburgh), 8 (1887): 116–21; “The equal rights movement,” University Quarterly Rev. (Toronto), 1 (1890): 139–45; “The Jesuits in Canada,” Presbyerian and Reformed Rev. (New York and Toronto), 1 (1890): 289–94; “Clerical conservatism and scientific radicalism,” Knox College Monthly and Presbyterian Magazine (Toronto), 14 (May-October 1891): 285–95; “General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in Canada,” Presbyterian and Reformed Rev. (Philadelphia), 6 (1895): 738–39; “Historical sketch of Knox College, Toronto,” Canada, an encyclopædia (Hopkins), 4: 211–21 (published in 1898); and “The union of the Christian churches,” Westminster (Toronto), [3rd] ser., 1 (July-December 1902): 26–29. His letters on the proposed federation of the Univ. of Toronto appeared in the Globe, 6 Dec. 1883: 4, and 24 Dec. 1883: 5, and were republished among other letters and addresses on the subject in the pamphlet Letters and speeches on the university question (Toronto, 1884), 8–14 and 14–22.

Evening Telegram (Toronto), 2 Dec. 1904. Gazette (Montreal), 2–3 Dec. 1904. Globe, 19 Nov., 2, 5–6 Dec. 1904. Manitoba Morning Free Press, 2–3 Dec. 1904. Ottawa Citizen, 2 Dec. 1904. Toronto Daily Star, 2–3, 5 Dec. 1904. Vancouver Daily Province, 2 Dec. 1904. Armstrong and Nelles, Revenge of the Methodist bicycle company. Canada Presbyterian Church, Minutes of the synod (Toronto), 1865, app.: xxxv; 1866: 31; app.: xxxv; 1867, app.: lviii; General Assembly, Acts and proc., 1870: 47; app.: lxxviii; 1873: 50. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898). The centenary of the granting of the charter of Knox College, Toronto, 1858–1958 (Toronto, [1958]). Donaldson Grant, “Principal William Caven, d.d., ll.d.,” Westminster, [3rd] ser., 1: 197–205. W. R. Hutchison, The modernist impulse in American Protestantism (Cambridge, Mass., 1976), 91–94. J. A. Macdonald, “A biographical sketch” in William Caven, Christ’s teaching concerning the last things, cited above, xiii-xxii; “Principal Caven – an appreciation,” Univ. of Toronto Monthly, 5 (1904–5): 133–38 and portrait facing p.133; “Rev. Principal Caven, d.d.,” Knox College Monthly and Presbyterian Magazine, 15 (November 1891–April 1892): 1–9. J. T. McNeill, The Presbyterian Church in Canada, 1875–1925 (Toronto, 1925). J. S. Moir, Enduring witness: a history of the Presbyterian Church in Canada ([Hamilton, Ont., 1974?]); “Forgotten giant of the church,” Presbyterian Record, 99 (1975), no.1: 14–15. Presbyterian (Toronto), new ser., 5 (July–December 1904): 701–8. W. J. Rattray, The Scot in British North America (4v., Toronto, 1880–84), 3: 826–27. R. E. Spence, Prohibition in Canada; a memorial to Francis Stephens Spence (Toronto, 1919), 278–320. Univ., of Toronto Monthly, 5: 79.

Cite This Article

Brian J. Fraser, “CAVEN, WILLIAM,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 22, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/caven_william_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/caven_william_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Brian J. Fraser |

| Title of Article: | CAVEN, WILLIAM |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | February 22, 2026 |