Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

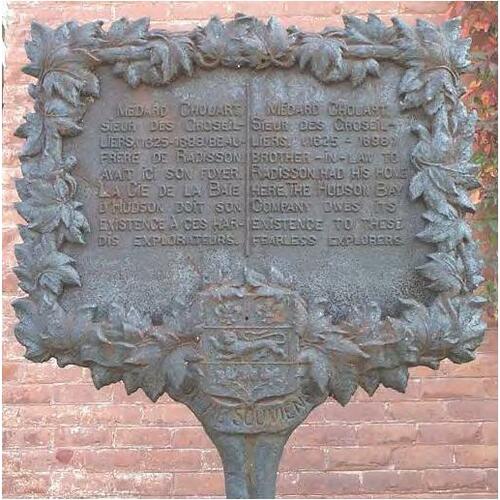

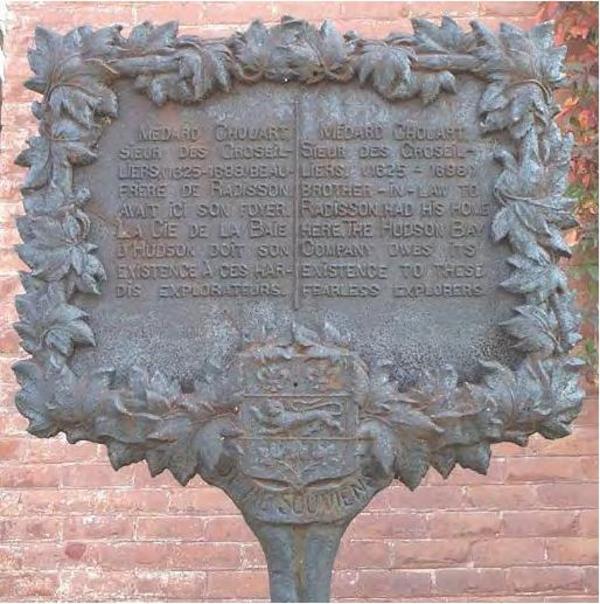

CHOUART DES GROSEILLIERS, MÉDARD, explorer and one of the originators of the HBC; baptized 31 July 1618, in the parish church at Charly-sur-Marne in the old French province of Brie, not far from Château-Thierry; d. 1696?

He was the son of Médard Chouart and Marie Poirier, whose farm, Les Groseilliers (the Gooseberry Bushes), may still be visited at Bassevelle, south of Charly. Little is known of Chouart’s family or early life, except that in 1647 his parents were living at Saint-Cyr and that he reached Canada at a youthful age, perhaps in 1641, having lived at some earlier time in the home of “one of our mothers of Tours,” according to Marie de l’Incarnation [see Guyart], the first mother superior of the Ursuline nuns in Quebec.

By 1646 the young man had become a part of the Jesuit mission of Huronia in modern Simcoe County, Ontario, perhaps as a donné, or lay helper, or, more likely, as a soldier. The Jesuit Relation of 1646 lists Des Groseilliers among the men “who returned this year from the Hurons.” He may well have been Mother Marie’s informant about recent geographical discoveries beyond the Hurons, which she recounts in a letter to her son, 10 Sept. 1646, mentioning “a great sea that is beyond that of the Hurons,” obviously a reference to either Lake Michigan or Lake Superior.

Shortly after his return, Des Groseilliers (he is usually so mentioned in contemporary accounts) married a young widow. The parish records of Notre-Dame de Québec state, under the date of 3 Sept. 1647, that he married Hélène, daughter of Abraham Martin (for whom the Plains of Abraham appear to have been named), and widow of Claude Étienne. Étienne was probably connected in some way with Charles de Saint-Étienne de La Tour, who is known to have made plans at one time to explore Hudson Bay with the financial aid of Major-General Edward Gibbons of Boston. In 1653 Des Groseilliers visited La Tour in Acadia and later sought financial aid in Boston for a projected trip to Hudson Bay. It is conjectured, therefore, that La Tour may have been the source of Des Groseilliers’ interest in and knowledge of Hudson Bay, which resulted in his trips to that region and the formation of the Hudson’s Bay Company.

A son, Médard, was born in 1651(?) and lived to maturity. Another child had died in 1648. Sometime in the early 1650s Hélène also died. His second wife was also a widow, Marguerite Hayet, former wife of Jean Véron de Grandmesnil, and mother of two sons, Guillaume and Étienne*, and possibly of a daughter. She was the daughter of Sebastien Hayet and Madeleine Hénaut and came from the parish of Saint-Paul in Paris. At the time of the wedding, which was celebrated on 24 Aug. 1653 in the parish of Notre-Dame de Québec, she was living in Trois-Rivières in the home of Jean Godefroy de Lintot, an interpreter famous in the annals of American exploration. Her half-brother was Pierre-Esprit Radisson*, the explorer and first known author of a descriptive account of the upper Great Lakes region, as well as Des Groseilliers’ companion on many exploratory expeditions.

To Médard and Marguerite were born: Jean-Baptiste (bap. 5 July 1654), Marie-Anne (bap. 7 Aug. 1657), Marguerite (bap. 15 April 1659), and Marie-Antoinette (bap. 8 June 1661).

These and the several preceding years were a harrowing period in New France. Iroquois incursions destroyed Huronia. Many French residents of hamlets along the St. Lawrence – including Jean Véron – were massacred, others were captured and often tortured to death. The result of these raids was the almost complete cessation of the traffic in furs, heretofore brought annually from the region between the Hurons and the far western tribes, who now were also driven from their homes in what the habitants of New France called the “pays d’en haut,” or the “country of the Ottawa Indians.” Since New France’s only export of consequence was furs, it looked for a time as though the country must be abandoned. At this juncture Des Groseilliers and an unknown companion came to the rescue.

Huron and Ottawa Indians reached Trois-Rivières in a roundabout way in the spring of 1653 and explained their predicament. They said that they were now hiding from the Iroquois in a region beyond Huronia and had a big accumulation of furs and that they hoped to come down the following year in sufficient numbers to defy the Iroquois.

In 1654 a peace was arranged between the French and the Iroquois and the western Indians did arrive late in the summer, bringing furs and news of “a great river” above their country “which empties into a great sea.” This was enticement enough for Des Groseilliers. When the tribesmen returned to their homes, he and another man were with them to ferret out the hiding-places of the displaced natives, formerly the mainstay of New France’s commerce.

It has been assumed by most historians that Radisson was Des Groseilliers’ companion, but the facts disprove this assumption. Though the young brother-in-law claimed in his narrative of 1669 – which is our only available source of detailed information – that he accompanied Des Groseilliers, he was both too young to go on such an expedition and, in addition, is known to have been in Quebec during the period of the trip, for on 7 Nov. 1655 he signed a deed of sale in that city (Greffe d’Audouart).

Just where Des Groseilliers and his companion journeyed cannot be stated in detail, for the Radisson narrative in the French language has been lost and only a contemporary translation has survived – a translation by an unknown person who was unacquainted with conditions among the natives of North America and who surely did not improve an already confused and difficult manuscript. However, it is possible to follow the explorers along the route that soon became the usual one for fur-traders, for Radisson’s descriptions of numerous places enable us to follow him up the Ottawa River to Lake Nipissing, down the French River to Georgian Bay and into Lake Huron, even though there were as yet almost no geographic names in the whole western country. We can also follow them south of the traders’ route in Lake Huron, past deserted Huronia, and probably through Lake St. Clair to the site of Detroit. After the “detroit” between Lake Huron and Lake Erie it is more difficult to find their track. Seemingly they crossed over the lower Michigan peninsula into Lake Michigan and followed its west shore up to the Straits of Michilimackinac. The return trip to Quebec again is plain, for Radisson could always describe clearly any region with which he was well acquainted.

For Des Groseilliers the trip’s significance lay in the fact that he learned about the region west and south of Hudson Bay. Radisson writes: “We had not a full and whole discovery, wch was that we have not ben in the bay of the north, not knowing anything but by report of ye wild Christinos [Crees].” The Jesuits in New France were much impressed by the new geographical facts afforded by the report of the two men upon their return, and they devote considerable space to it in their Relation of 1655–56. An outstanding merchant of New France, Charles Aubert* de La Chesnaye, also recalled many years later “the two individuals who returned in 1656, each one with from 14 to 15 thousand livres, and brought with them a flotilla of Indians with 100,000 écus worth of treasures.”

The years from 1656 to 1659 are well documented for Des Groseilliers’ career. We know when his children were born and by whom they were baptized, that his home was in Trois-Rivières, and that he and his wife were becoming well-to-do. The village records have been preserved and contain many documents relating to Des Groseilliers and his wife. They were a litigious pair and were often in court – to the satisfaction of historian and biographer, if not to neighbours of this typically frontier family.

Court records cease abruptly for Des Groseilliers, however, in the summer of 1659. The reason, of course, was that he had gone once more into the Upper Country. Radisson by this time was back from two sojourns in the Iroquois country – one while a captive and the other as a member of a Jesuit missionary venture at Onondaga – and he was now old enough to accompany his brother-in-law. The two men set out in August 1659 and returned the following summer.

Again we must rely principally upon Radisson’s narrative of 1669 for details, but this time it is clear and consecutive. The governor, Pierre de Voyer* d’Argenson, was opposed to the expedition unless one of his men accompanied the explorers. Des Groseilliers in his blunt fashion announced that it was a case of “discoverers before governors” and slipped away undetected, largely because he was captain of the borough of Trois-Rivières and had “the keys of the Brough,” according to Radisson.

They met returning tribesmen farther up the St. Lawrence, who helped repel an Iroquois attack on the Ottawa River; followed the traders’ route to Lake Huron; passed along its northern coast to Sault Ste. Marie; portaged around the falls there; idled along the picturesque south shore of Lake Superior, whose sand dunes and portalled cliffs delighted the young Radisson; and came to the large inlet known today as Chequamegon Bay but given no name by Radisson in his account. Here, beyond the sand spit (La Pointe) guarding the bay from northeasters and close to the Apostle Islands, the displaced Ottawas, Hurons, and Chippewas turned inland to their temporary homes, probably on Lac Courte-Oreille, or Ottawa Lake. After caching their trade goods and building a rude shelter, the Frenchmen also went on to that lake.

The following winter was a severe one. Heavy snow-falls made it impossible to kill game for food and starvation faced even the white guests more than once. Toward spring the Sioux, the permanent residents of much of the region south and west of Lake Superior, sent representatives and gifts, inviting the strangers to visit them. Before doing so the Frenchmen witnessed a great Feast of the Dead, faithfully described in Radisson’s narrative, our earliest account of the culture of the “eighten severall nations” that he says participated in the festivities.

Six weeks, according to Radisson, were then spent among the Sioux, who were practically unknown to white men before this time. Spring having now begun, the two white men returned with some Chippewas to their cache near La Pointe, and then crossed Lake Superior to its north shore.

Here today is Gooseberry River, which began to appear on French maps soon after Des Groseilliers’ visit as Rivière des Groseilliers and may well have been named for him, although it was moved up and down that shore at the whim of the cartographer. As late as 1775 the Pigeon River, now the boundary line between Canada and the United States just west of Lake Superior, was called the River “des Groseilliers” by Alexander Henry* in the entries for 8 and 9 July in his Travels & adventures in Canada . . . between the years 1760 and 1776, ed. James Bain (Toronto, 1901), 236, 237.

Though Radisson injects at this point in his narrative a very brief account of a trip from Lake Superior to Hudson Bay, it is certain that this was wholly imaginary and only inserted in 1669 to further his plans of the moment, namely, a trip to Hudson Bay financed by Londoners. Such a journey could not have been made in the remaining time in 1660 before the return trip to Quebec. While on the north shore the explorers visited the Cree Indians and probably learned of the Grand-Portage – an important spot in North American history as the subject of international dispute over ownership (1783–1842) and because it was the beginning of practically the only good canoe route to the far west (via Pigeon River and the lakes and rivers of the present international boundary line).

The summer months of 1660 were spent in returning to the lower St. Lawrence. Accompanying the two Frenchmen were many Indians and a rich harvest of furs. At the Long Sault on the Ottawa River Radisson describes the remains of the Dollard massacre, which had occurred a few weeks earlier, and mentions that it was here on an earlier trip that Des Groseilliers was shipwrecked and lost his diaries. A document of 22 Aug. 1660 (Greffe de Bénigne Basset) shows that Des Groseilliers stopped briefly in Montreal to make a business agreement with one of the hamlet’s outstanding merchants, Charles Le Moyne de Longueuil (quoted in BRH, XX (1914), 188, but wrongly dated).

The Jesuits were eager for news of the countries to the west and duly reported in the year’s Relation their interviews with Des Groseilliers upon his return. Three of their company, including the first missionary to Lake Superior Indians, Father René Ménard, and six other Frenchmen, five of them traders, immediately started back with the returning tribesmen, and from that moment there was never a time when French fur-traders were absent from the pays d’en haut as long as it was claimed as a part of the French empire. Those who went into the Ottawa country in 1660 to trade have been identified by Louise Phelps Kellogg as Jean-François Pouteret de Bellecourt, dit Colombier; Adrien Jolliet (elder brother of Louis Jolliet); Claude David; the Quebec joiner Pierre Levasseur, dit L’Espérance; and a man named Laflèche, probably related to the Nipissing interpreter Jean Richer.

There is good evidence that the western trip of the two brothers-in-law saved the colony from economic ruin – probably preserved its very existence – but Governor d’Argenson seized the explorers’ furs, fined them, and, according to Radisson, threw Des Groseilliers into jail, presumably for departing without his sanction. This treatment infuriated both men and they resolved to seek assistance for their trading and exploration plans from New France’s enemies and rivals, the English in New England or the Dutch in New Holland.

It was a crucial moment. A decision in ownership of much of the continent and possession of the lucrative beaver trade was in the making. Some persons at the time believed that the defection of these two men decided the issue. Two perspicacious individuals, Marie de l’Incarnation and Father Paul Ragueneau (long at the head of Jesuit missions in New France and formerly the tutor of the Great Condé), were quite explicit in their letters to France (Marie Guyart de l’Incarnation, Lettres (Richaudeau), II, 293; BN, Mélanges de Colbert, 125, Ragueneau to Colbert, 7 Nov. 1664), linking the English conquest of New Holland in 1664 with the two renegades. A train of events, therefore, was started by them which would come to an end only with the British conquest of Canada in 1763.

The details of Des Groseilliers’ preparations for his next venture – to the Ottawa country by way of Hudson Bay – are rather involved. With his brother-in-law he eventually departed down the St. Lawrence in a bark canoe with ten voyageurs in late April or early May 1662, having returned the previous year from a trip to France. There an agreement had been made with a La Rochelle merchant, Arnaud Peré (brother of the explorer-trader Jean Peré, for whom the Albany River was long named by the French), to supply a vessel to take him to Hudson Bay from Île Percée. Something – perhaps Jesuit opposition – fouled his plans at Île Percée and turned him instead to Boston.

In Massachusetts he found men willing to venture with him, and several journeys to Hudson Bay were begun. Because of inclement weather, lack of proper provisions for an arctic undertaking, and other impediments, nothing practical was accomplished, however, though New Englanders were then probably better versed than anyone else in knowledge of the Hudson Bay area. Something worthwhile was achieved, nevertheless, for commissioners, including Sir George Cartwright, from the newly restored king of England, sent to win truculent New Englanders’ support for the new régime in England, met the Frenchmen, learned of their plans, and persuaded them to go to Charles II’s court. After capture on the high seas by a Dutch caper (privateer) and a landfall in Spain, the two explorers went thence to London, Oxford, and Windsor, arriving in time to witness the ravages of the plague in 1665 and the Great Fire of 1666.

The next three years saw the fruition of Des Groseilliers’ plans, though many mistakes and false starts were made, and though Dutch and French adventurers tried to anticipate him in his first sea voyage into Hudson Bay. Finally in 1668 two small vessels carrying the brothers-in-law departed from England for the Bay. Des Groseilliers’ vessel, captained by a New England mariner, Zachariah Gillam, found the difficult way into the “Sea of the North” and anchored at the mouth of a river, which the Englishmen named the Rupert and where they established Charles Fort and spent the winter. Radisson’s voyage in a naval vessel lent by the king was unsuccessful, and he returned to London to spend the winter completing the writing of his narrative, which had been commanded at an interview with the king. For its translation five pounds sterling was paid in June 1669 to an unknown translator, perhaps Nicholas Hayward, later the Hudson’s Bay Company’s French interpreter. The original French manuscript has been lost, but the translation has been preserved in the papers of Samuel Pepys in the Bodleian Library in Oxford, England.

Meantime the English financial backers of the two Canadians formed a corporation, which received its charter on 2 May 1670 (o.s.) and has been known since as the Hudson’s Bay Company. Like several of its predecessors in the settlement of English colonies in North America it was a joint stock company with governing powers and territorial rights in much of the northern part of the continent. It proceeded at once to establish settlements and to elect a colonial governor, Charles Bayly. Gillam and others captained its vessels, which henceforth were to maintain almost yearly communication between the Bay and the mother country.

From 1670 to 1675 the two Frenchmen were employed by the new corporation, making trips to the Bay, founding fur-trading posts, supervising trade with the Indians, and making trips of exploration. Their activity was watched with increasing apprehension by French and Canadian officials, especially Talon and Buade de Frontenac, as well as by Marie de l’Incarnation and the Jesuits, all of whom wrote letters to Colbert, to members of the French court, and even to other individuals, mentioning the English aggression and deploring the lack of effective French countermeasures. Talon attempted retaliation by sending Cavelier de La Salle, Jean Peré, and Simon-François Daumont de Saint-Lusson to the west in 1670 and 1671, and Father Charles Albanel and Paul Denys* de Saint-Simon to Hudson Bay in 1671. Frontenac was even more determined to outdo the English, and his response came in the form of Louis Jolliet’s journey down the Mississippi in 1673 and La Salle’s and Father Hennepin*’s trips on the same stream in ensuing years.

An attempt was made by the new English company to have Radisson found a colony on the west coast of Hudson Bay at the mouth of the Nelson River, but it was unsuccessful, as the diary of Thomas Gorst, a sort of supercargo on Des Groseilliers’ vessel of that year (1670–71), reveals. Nevertheless, the attempt was to prove of value some years later, when an earnest effort was made in the late 1680s to resolve the conflicting territorial claims of France and Great Britain in the Hudson Bay area. Then each side of the dispute tried to provide conclusive evidence that its explorers or traders had been first in various parts of that region. A year’s neutrality was decreed by the treaty of 16 Nov. 1686 to enable both sides to find the necessary evidence for specially appointed commissioners to adjudicate the issue (“Transactions betweene England and France relateing to Hudsons Bay, 1687,” PAC Report, 1883, Note C, 173–201). The names and journeys, or reputed journeys, of many persons were brought to the attention of the commissioners, and the North American adventures of Radisson, Des Groseilliers, Father Albanel, Saint-Simon, Jean Bourdon, Guillaume Couture*, the two brothers Jolliet, Le Moyne* d’Iberville, and others were taken up in their relation to the right of France to lay claim to parts of the Hudson Bay region. The Hudson’s Bay Company, on its part, supplied records of the two Frenchmen, of its ships’ captains, and of still earlier explorers operating under the British flag in the first half of the century. The year of neutrality had not ended when the “Glorious Revolution” took place in England, resulting in war between the two countries instead of the almost-achieved line of demarcation (the 49th parallel was the suggestion) between New France and British possessions to the north.

In 1676 Des Groseilliers and Radisson returned to Canada, after spending a year in France. They had gone to that country after Father Albanel had seduced them back to a French allegiance while the priest was held in England by the Hudson’s Bay Company, following his 1674 journey to Hudson Bay, where he had been captured by the English. By the early 1680s the two Frenchmen were having another adventure in Hudson Bay, this time in the employ of a Canadian company, the Compagnie du Nord, under the direction of Aubert de La Chesnaye.

This man was a Canadian who combined knowledge, wealth, influence, and determination to an unusual degree. His conviction was that the salvation of Canadian trade lay in a maritime approach and increases in the quantities of coat beaver, obtainable chiefly from the west coast of Hudson Bay and beyond. In Paris in 1681 he got in touch with Radisson and laid plans for future action by means of a Canadian fur-trading company. Colbert was interested and sub rosa granted a charter in 1682 under the name of “La Compagnie de la Baie d’Hudson” (Compagnie du Nord). However, there was no official sanction of the scheme and that fact produced confusion and misunderstandings in Canada, where Frontenac refused a permit to Aubert de La Chesnaye when he and Radisson returned to that country in 1682. Finally a permit to fish on the coast of Anticosti was secured from the governor. He was soon recalled to France and Le Febvre de La Barre served in his place.

La Chesnaye’s plan actually was to get into the coat beaver country at the spot at the mouths of the Nelson and Hayes rivers where Radisson had attempted to found a colony in 1670. Unfortunately for the Canadians, the Hudson’s Bay Company in that same year, 1682, reverted to its original plan; and Benjamin Gillam*, of Boston, the son of Captain Zachariah Gillam, planned an interloping venture to the same spot. Therefore, in September 1682 three separate groups appeared there and it became a question of which one arrived first or could outwit the others. Later each group claimed prior occupancy and it is now impossible to judge from the many accounts of practically guerrilla warfare in the Bay which claim is correct. The experience and knowledge of wilderness ways possessed by the two Canadians soon determined the issue in their favour and they came out apparent victors, taking most of the others captive, including John Bridgar, the newly appointed governor of the new English colony, securing its furs, and burning its forts. However, the Canadian company, in endeavouring to evade payment of the quart on the furs to the farmer-general in Quebec, brought about a governmental decree, which sent most of the Canadian participants, including Des Groseilliers and Radisson, to France for adjudication of the case.

In Paris they found that Colbert was dead and they were met with a complaint from the English company, whose governor was James, Duke of York, brother of the king and a person not to be trifled with by the French (he was their one hope of reconverting England to the Roman Catholic faith). The upshot of the ensuing intrigue between a special envoy sent from the English court, his spy, ministers of Louis XIV, and others, was that Des Groseilliers returned to his home in Canada and Radisson went back to the Bay in 1684 in the employ of the company whose post and furs he had just purloined.

There he tricked his nephew, Jean-Baptiste Chouart, into yielding up the post and the furs that the young man had been protecting during the absence of his father and uncle, transported him and his companions to England in the same year, enlisted them in the employ of the company, and took them back to the Bay with him on his next trip in 1685. Des Groseilliers’ son has been regarded by some as the first white man to explore far into the hinterland back of Port Nelson, even anticipating Henry Kelsey* in this respect. Whether he did so at all is uncertain; and if he did go into the interior, it is uncertain whether he acted in the interest of the company or in an endeavour to carry out a scheme hatched by Daniel Greysolon* Dulhut and other Canadians, who were trying to get him back to New France by way of Dulhut’s post on Lake Nipigon. In any event, he stayed in the Bay until 1689, then returned to London, where his later career is unknown.

Likewise unknown is the elder Chouart’s fate. He rejected a Company offer to re-enter its service, and sometime between April and November 1684 returned to New France. Where and when he ended his adventurous career is uncertain. In the 1690s Radisson, still serving the Company in London, stated that his brother-in-law had “died in the Bay.” However, the date he gave – about 1683 – is an impossible one, for we know that Des Groseilliers was alive beyond that time. Some other faint evidence points to Sorel, about 1696, as the place and time of his death. There is no proof of either conjecture. A Marguerite Des Groseilliers was interred in Trois-Rivières in 1711. Whether she was his wife or his daughter is uncertain.

Des Groseilliers’ career was not merely adventurous and romantic. His daring led him to explorations that were crucial for French and English territorial claims in North America; and his intelligence enabled him to see quickly and clearly that the easiest and quickest route to the richest fur region of the continent was not by the difficult, dangerous, and time-consuming canoe highway through the Great Lakes and along the Grand-Portage–Lake of the Woods waterway, but across Hudson Bay in ships carrying large cargoes quickly and easily to the very heart of the continent. In addition he had the address sufficient on the one hand to assuage Indian fears of white men and on the other to persuade European officialdom and businessmen to carry out his ideas. The Hudson’s Bay Company continues to this day to prove the correctness of his judgement.

For MS sources see Nute, Caesars of the wilderness, 359–63. Coll. de manuscrits relatifs à la Nouv.-France, I, 245–61. Marie Guyart de l’Incarnation, Lettres (Richaudeau), I, 292; II, 67, 447, 448. HBRS, V, VIII, IX (Rich); XI, XX (Rich and Johnson); XXI, XXII (Rich). JR (Thwaites), XXVIII, 229; XL, 219–21, 235–37, 296 n.11; XLIII, 155–57. [Pierre-Esprit Radisson], Voyages of Peter Esprit Radisson, being an account of his travels and experiences among the North American Indians, from 1652 to 1684, transcribed from original manuscripts in the Bodleian Library and the British Museum, ed. G. D. Scull (Prince Soc., XVI, Boston, 1885; New York, 1943), 123–34, 172, 174, 175, 209–17.

J. B. Brebner, The explorers of North America 1492–1806 (New York, 1955). L. P. Kellogg, The French régime in Wisconsin and the Northwest (Madison, 1925), 114, 115. Nute, Caesars of the wilderness.

The explorations of Pierre Esprit Radisson from the original manuscript in the Bodleian Library and the British Museum, ed. A. T. Adams (Minneapolis, 1961), a recent edition of the Voyages, offers another theory to explain the discrepancies in the sources.

Revisions based on:

Arch. Départementales de l’Aisne (Laon, France), “Reg. paroissiaux et d’état civil,” Charly-sur-Marne, 31 juill. 1618: archives.aisne.fr/archive/recherche/etatcivil/n:11 (consulted 18 Sept. 2015). Bibliothèque et Arch. Nationales du Québec, Centre d’arch. de Québec, CE301-S1, 3 sept. 1647, 24 août 1653. R.-Y. Gagné, “Médard Chouart et ‘les Groseilliers,’” Soc. Généal. Canadienne-Française, Mémoires (Montréal), 57 (2006): 291–93.

Cite This Article

Grace Lee Nute, “CHOUART DES GROSEILLIERS, MÉDARD,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 27, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/chouart_des_groseilliers_medard_1E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/chouart_des_groseilliers_medard_1E.html |

| Author of Article: | Grace Lee Nute |

| Title of Article: | CHOUART DES GROSEILLIERS, MÉDARD |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1966 |

| Year of revision: | 2016 |

| Access Date: | February 27, 2026 |