Source: Link

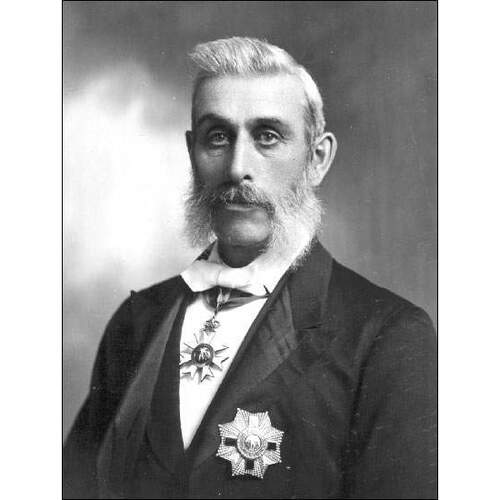

WINTER, Sir JAMES SPEARMAN, lawyer, judge, and politician; b. 1 Jan. 1845 in Lamaline, Nfld, eldest son of James M. Winter and Harriet Pitman; m. 22 Oct. 1881 Emily Julia Coen of St John’s, and they had eight children; d. 6 Oct. 1911 in Toronto and was buried 14 October in St John’s.

The son of an outport customs officer, James Winter was sent to his father’s home town of St John’s to be educated at the General Protestant and Church of England academies. In 1859 he became a merchant’s clerk, but two years later he began the study of law with Hugh William Hoyles*. He was called to the bar in 1867 and developed a busy law practice, from 1881 in partnership with Donald Morison.

Winter’s political career began in 1873, when he won a seat in Burin district (where he had been born) in support of Frederic Bowker Terrington Carter*’s Conservative party. It was an election in which the Orange order played a significant role. Since Winter was by this time master of the Royal Oak Lodge in St John’s, he was no doubt selected for a relatively safe seat. His early success in public life was probably due in part to his prominence in the order, of which he was provincial grand master from 1878 to 1885. Winter was ambitious and astutely linked his fortunes with those of William Vallance Whiteway*, who in the mid 1870s was clearly the coming man in Newfoundland politics. Winter was elected speaker for the 1877 and 1878 sessions of the assembly.

He was both more conservative and less visionary than many others in Whiteway’s party, and his support was not unquestioning. Though he was prepared to endorse a railway-building policy, in 1881 he strongly and eloquently criticized the first railway construction contract to build a line from St John’s to Halls Bay and was among the eight members who voted against it. Most opponents of the contract moved into opposition and joined the largely mercantile New party, formed to oppose Whiteway’s progressive policies. Winter, however, remained with the Conservatives, having been promised the post of solicitor general, which he received once he had narrowly retained his seat at Burin in the 1882 election.

Though the government won the election comfortably, Whiteway had done so by allying himself with the Liberal party – almost exclusively Roman Catholic in composition – to compensate for the loss of his mercantile supporters to the New party. This alliance, and Winter’s continuing loyalty, was placed in jeopardy by an Orange-Catholic affray at Harbour Grace in December 1883. Winter and Whiteway acted as the crown prosecutors in the trials of 19 Catholics accused of murder, trials which accentuated the bitterness prevailing in the community. Two acquittals enraged many Protestants, including Winter, and led to an alliance – there had been informal links for some time – between the New party and a political committee formed by the Orange order in 1883 and dominated by Alexander James Whiteford McNeily. Motives were mixed. The protection of Protestant rights was the priority for some, but for others the alliance was primarily a manœuvre to weaken the Whiteway government and, with luck, replace it with a new administration more responsive to mercantile needs. For the time being Winter, still grand master, remained in the government, a decision that caused considerable strain within the order.

In February 1885 Orangemen and New party members in the assembly combined to break Whiteway’s alliance with the Catholic Liberals and force them into opposition. The next step in the strategy was to unite all non-Liberals in a new Protestant party (to be known as the Reform party) under Winter’s leadership, Whiteway being provided with a suitable position outside politics. Since Whiteway at first refused to cooperate, Winter resigned from the government and the party in June. In October, however, Whiteway agreed to retire and to merge his now truncated party with the Reformers. A condition was a new, mutually acceptable leader in the person of Robert Thorburn*. Winter had to content himself with the post of attorney general.

A general election, characterized by fierce sectarian rhetoric, was held later that autumn. Winter ran successfully for Harbour Grace, at the behest, apparently, of the local Orange lodge. The Reform party was confirmed in power. The religious cry, fomented by Orangemen and manipulated by anti-Whiteway politicians, had done its work and was speedily discarded. Within a year several leading Catholics had joined a suddenly tolerant Reform government, and the old Liberal party ceased to exist. The Reformers could now consolidate their position and develop alternatives to Whiteway’s stress on railways and interior development. It was Winter’s chance also, as one of the most experienced and influential members of the government, to establish himself as a major, even dominant, public figure in the colony. Both he and the party missed the opportunity.

The government’s central problem was to reconcile its inherent conservatism with the price demanded by the Liberals for amalgamation, and also with the increased expenditures dictated by economic depression. It instituted policies hostile to French fishermen – Winter introduced the famous Bait Act – on both the banks and the Newfoundland treaty shore and began to pressure the Colonial Office for permission to negotiate a reciprocity treaty with the United States. It established an embryonic fisheries department [see Adolph Nielsen*] and, in its first session at least, showed an imaginative interest in rural development. At the same time, however, the government undertook heavy expenditures on public works, floated the colony’s first foreign loans, and by the end of its term was involved in railway building. In short, it failed to develop a viable alternative to Whiteway’s progressive nostrums.

Moreover, the government’s stability was seriously damaged when Winter unwisely decided to try to manœuvre the colony into confederation. Disturbed by Newfoundland’s desire for an independent reciprocity treaty with the United States, the Canadian government became interested in union for the first time since the 1860s. Sir Charles Tupper in October 1887 visited St John’s for talks, which proved inconclusive. At the Washington fisheries conference shortly afterwards, he had the opportunity for longer discussions with Winter, who was representing Newfoundland. The latter returned to St John’s in February 1888 with an elaborate scheme for union and Canadian agreement to a formal confederation conference when he gave the word. The Reform party was so divided on the issue that although an invitation from Ottawa arrived, no delegation was sent; and the very fact that it had flirted with confederation weakened its electoral chances. The following year the government was soundly defeated by a refurbished Whiteway party, now calling itself “Liberal.” Sir James – he had received a kcmg in 1888 for his services in Washington – ran again at Harbour Grace, and in spite of heavy, and probably highly irregular, expenditures in the district, he came at the bottom of the poll with a miserable 604 votes. This result may also have reflected the resentment of local Orangemen at what they perceived to be Winter’s and the government’s betrayal of the order.

He remained politically active, taking a leading part in the agitation in 1890 against an Anglo-French modus vivendi governing the lobster fishery on the French Shore. Seeking to portray the Liberals as unable to defend colonial interests in the face of French aggression, opposition politicians created a good deal of patriotic excitement. Winter, Alfred Bishop Morine*, and Patrick J. Scott* went to England as “people’s delegates,” their task being to embarrass Whiteway and promote an extreme “Newfoundland rights” view of the controversy. To this end they published a pamphlet in London, gave numerous interviews, and in general helped to create the impression that the colony was in a state of virtual insurrection. Later that year Winter acted for the plaintiff in the famous case of Baird et al. v. Walker. James Baird, a Tory merchant and owner of a lobster factory closed down under the modus vivendi, successfully sued the commodore of the Newfoundland naval squadron for trespass. The victory embarrassed the British government and helped precipitate a crisis within the Whiteway administration.

Winter was actively involved in plans to create a confederate party, together with Morine and other former members of the Reform caucus. They hoped for Canadian help, since the Whiteway government had sought to negotiate an independent reciprocity treaty with the United States and when that failed, had launched retaliatory actions against Canadian fishermen. In the fall of 1891, under the name of Mr Spearman, Winter went secretly to Ottawa for discussions with members of the federal government, hoping for commitments that he did not receive. Indeed, the Newfoundland confederates persistently overestimated Canadian enthusiasm for union. Morine in the assembly attempted to sabotage potentially anti-Canadian actions and corresponded regularly with federal justice minister Sir John Sparrow David Thompson*. In November 1892 Winter won a by-election at Burin, expecting to take over the party leadership in time for the next election. He played an active role in the 1893 session, but then in May accepted an appointment to the Supreme Court. Governor Sir John Terence Nicholls O’Brien* thought Whiteway – who detested Winter – had made the offer unwillingly, even if it did remove a prominent opponent, but had realized there was no alternative candidate. The move ended the nascent confederate party.

It was perhaps unfortunate that, as a formerly prominent Tory, Winter in February and March 1894 presided over the first case heard under the Controverted Election Act (1887), which he had introduced when attorney general. It was one of a large number of cases brought against Liberals by defeated Tories in the wake of the 1893 election. Not surprisingly, when Winter unseated and disqualified the Liberals in question, he was roundly vilified for partisanship. His law may have been correct, but as a member of the Colonial Office noted, it appeared to be “a case of Satan rebuking Sin.”

Though he seems to have been a competent judge, Winter resigned from the bench in November 1896. Judicial salaries had been reduced in the wake of the 1894 bank crash [see James Goodfellow*; Augustus William Harvey*], and financial needs, as well as constant criticism from the Whiteway government, appear to have driven him back to private practice. Soon after, he was approached by leading Tories to become party leader, and he did so in February 1897. That fall the party won the general election with a ten-seat majority, riding on discontent at a collapse in fish prices, disillusion with the divided and tired Liberals, and a series of judicious promises.

Morine was the dynamo of the new government, which proved at first to be active and energetic. The civil service was pruned and reorganized, the tariff reformed, and the colony’s financial administration made more efficient. The British government was persuaded to institute a royal commission on the French Shore question. However, a major crisis erupted when, early in 1898, the government introduced a new railway contract with Robert Gillespie Reid*. Winter and Morine were both closely connected to the Reid interest: Winter had been Reid’s standing counsel in the early 1890s (a post to which Morine had succeeded) and had prepared the 1893 Reid agreement, which was now to be replaced. Probably drafted by Winter, the proposed contract envisaged major, indeed dramatic, concessions. It was highly controversial. Though it passed the legislature, and in the process split the Liberal opposition, it helped ruin the Winter government. Robert Bond*, leader of the anti-contract Liberals, aided by the meddlesome governor, Sir Herbert Harley Murray*, launched an emotional and nationalistic crusade against it. When the Colonial Office refused to intervene, Murray turned on the ministry and dismissed Morine from the executive on the grounds that he was Reid’s lawyer.

Winter was now superficially in a strong position, with the Liberals divided and his main rival demoted. But he failed, once again, to turn the situation to his advantage. Instead the party split in two. Early in 1898 Winter had agreed to take the chief justiceship and hand over the premiership to Morine at the end of that year’s session. Many party members had objected, with the result that the change-over was postponed. In the new year, while Winter was in Washington representing the colony at meetings of the joint high commission, Morine began to agitate for the agreement to be honoured. Winter was again persuaded to refuse. The government nearly collapsed and would have done so had Winter’s attempt to join his following with Bond’s succeeded. Though Governor Sir Henry Edward McCallum mediated an agreement whereby Morine rejoined the cabinet and Winter agreed to resign at the end of the year, the party remained plagued by unpopularity and internal warfare. Finally, in November Winter demanded and obtained Morine’s resignation.

In February 1900 Winter called a special session of the legislature to renew legislation enforcing the Anglo-French fisheries treaty. Unexpectedly, Bond brought down the government on a no-confidence vote, and on 5 March Winter resigned. By the time the assembly reconvened, Winter had undergone the further humiliation of seeing Morine elected party leader. Pathetically, he appealed to the speaker and to Bond for recognition as leader of the opposition. The request was refused. Winter absented himself from the assembly, and his supporters did the same or voted with the government. He applied unsuccessfully for a position in the colonial service.

Out of politics, Winter returned to his law office. Complaining that he had lost much of his practice, he pleaded in vain with Bond for a judgeship. He became increasingly reliant, it seems, on the largesse of the Reid company. In 1904 he was persuaded to run in his old district, Burin, for the United Opposition party, only to be heavily defeated. There was no hope of preferment until Bond was defeated in 1909 by Sir Edward Patrick Morris*, a former law pupil and another Reid supporter. The plum was the appointment of this “pleasant if dull old man” (as Winter was known at the Colonial Office) to help prepare and argue the Newfoundland section of the British case at the North Atlantic fisheries arbitration. He joined Canadian counsel – who were effectively in charge of the case – in London during the summer of 1909 and returned the following year to help complete the counter-case and appear before the tribunal at The Hague. If his performance was undistinguished, it may well have been the result of poor health. He died little more than a year after he returned home.

Winter never fulfilled his early promise. Though intelligent and apparently an able lawyer, he lacked, as Morine put it, “quickness and firmness in public affairs,” and he was a clumsy, rather indecisive party leader. He had none of Whiteway’s or Bond’s charisma and was never a popular figure. His tortuous political career gave him several opportunities to establish himself as a dominant figure. Both chance and character conspired to prevent him.

The pamphlet produced by Winter with P. J. Scott and A. B. Morine was published under the title French treaty rights in Newfoundland: the case for the colony, stated by the people’s delegates (London, 1890).

British Library (London), Add.

Cite This Article

James K. Hiller, “WINTER, Sir JAMES SPEARMAN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 26, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/winter_james_spearman_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/winter_james_spearman_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | James K. Hiller |

| Title of Article: | WINTER, Sir JAMES SPEARMAN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | February 26, 2026 |