Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

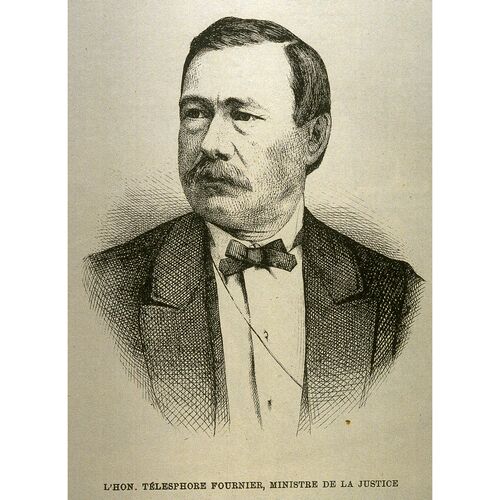

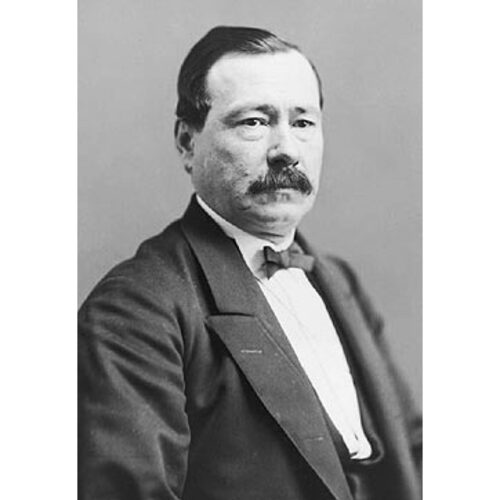

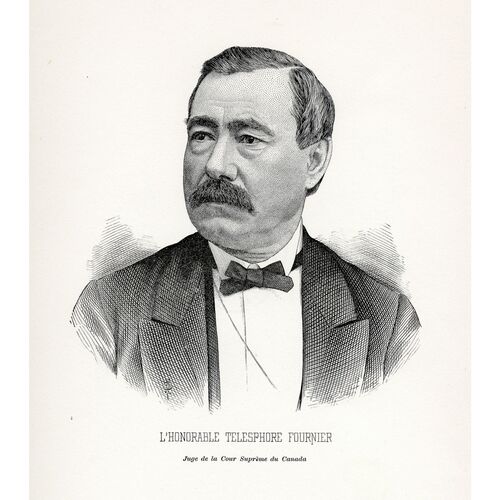

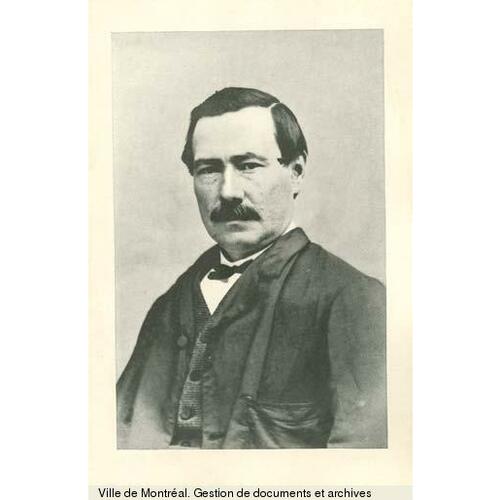

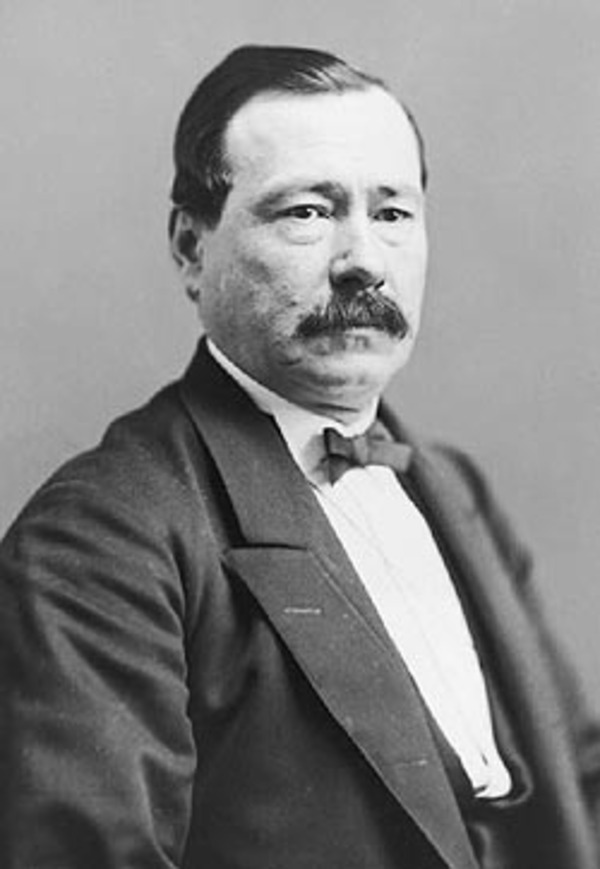

FOURNIER, TÉLESPHORE, lawyer, publisher, journalist, politician, office holder, and judge; b. 5 Aug. 1823 in Saint-François-de-Sales-de-la-Rivière-du-Sud, Lower Canada, son of Guillaume Fournier and Marie-Archange Morin; m. 22 July 1857 Hermine Demers in Saint-Pierre-les-Becquets (Les Becquets), and they had nine children; d. 10 May 1896 in Ottawa.

From an early age Télesphore Fournier displayed real ability. In 1835 his father enrolled him in the Séminaire de Nicolet, probably with the financial help of Claude Dénéchau*, for whom he worked as a miller. Fournier headed his class and was permitted to skip the fourth-year program, Poetry. He was good at languages, mathematics, and public speaking. His classmate and friend Antoine Gérin-Lajoie* later recalled that “he was already showing the delicate sensibility, the sense of honour, the proud and independent spirit that always made him stand out in the world.”

In 1842 Fournier began his legal training with lawyer René-Édouard Caron*. At 19 he was one of the educated young men in Quebec City who were acutely conscious of the reverberations of the failure of the 1837 and 1838 uprisings and were wondering about the destiny of French Canadian society. He frequented the Hôtel de la Cité, the Hôtel de Tempérance, and the premises of the newspaper Le Fantasque, where Pierre-Joseph-Olivier Chauveau*, Joseph-Charles Taché, James Huston*, Auguste Soulard*, and other young men exchanged ideas. He fell under the influence of its editor, Napoléon Aubin*. On 4 Oct. 1843, along with Aubin, Taché, and Marc-Aurèle Plamondon, Fournier helped found the Société Canadienne d’Études Littéraires et Scientifiques, of which he was elected deputy secretary. Despite its fleeting existence this society, which had some 30 members, played a part in the development of intellectual life at Quebec. Its members were interested in the progress of the arts and professions. They held a weekly study session, and in January 1844 inaugurated courses open to the public.

Fournier was called to the bar on 10 Sept. 1846 and practised his profession at 7 Rue Haldimand in Quebec. Later he went into partnership with John Gleason (1858–65), Charles-Alphonse Carbonneau (1872–73), and, lastly, Matthew Aylward Hearn and Achille Larue under the name of Fournier, Hearn et Larue (1874–75). Judge Thibaudeau Rinfret*, recording oral tradition, notes that in court “he spoke slowly. He pleaded briefly but with sincerity, elegance, and clarity . . . careful in his choice of language and the construction of his sentences.” He is said to have been able to grasp instantly how the law applied in particularly complex cases. His talent was recognized by his peers, who elected him bâtonnier of the Quebec bar on 1 May 1867 and bâtonnier général of the provincial bar the following year.

Fournier was active in the legal world and in politics at the same time. In 1847 he took part in the campaign of the Comité Constitutionnel de la Réforme et du Progrès, of which René-Édouard Caron was chairman, and he was assistant to the recording secretary Napoléon Aubin. In 1849 his name appeared with those of Aubin, Plamondon, and Soulard at the head of a petition in favour of annexation to the United States. In the 1854 elections to the Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada he was defeated in Montmagny by Louis-Napoléon Casault, a native of the region and brother of Louis-Jacques*, the rector of the Université Laval. The leaders of the Rouge party attributed the defeat of all their candidates east of Champlain riding to the absence of a forceful newspaper. They urged Fournier to defend the liberal cause with his pen. On 20 Nov. 1855 he launched Le National, a bi-weekly of which he was co-owner and co-editor, along with Pierre-Gabriel Huot and Plamondon. This four-page paper had a format that was modern for the period: a literary page consisting of a serialized novel; a page of European news; a page of local news where political events served as a pretext for party and ideological discussions; and a page of advertisements. It professed itself resolutely democratic. Fournier struggled for a Canadian society that would enjoy independence, liberalism, and modernized social and political institutions. His short-term aims were: repurchase by the crown of the privileges attached to seigneurial tenure; reform of the electoral system; opening up of uncultivated lands for settlement; equitable division of public funds between Upper and Lower Canada; and independence of the assembly in relation to the executive, particularly through the exclusion from it of those in the pay of the government. In the longer term Fournier worked for the dissolution of the union of the two Canadas. Le National fought fiercely against its rivals: Le Canadien, the government newspaper, and Le Journal de Québec, the organ of the versatile Joseph-Édouard Cauchon*. A cutting article gave rise to an absurd duel between Fournier and Michel Vidal, editor of Le Journal de Québec, which is wrapped in mists of legend that historians have not yet dispelled. On 9 June 1859, having run out of money, Le National ceased publication.

Fournier capitalized on his reputation as a lawyer, journalist, and public speaker to run once more for the legislature, although he had again been defeated in Montmagny in 1857. He vainly tried to win election to the Legislative Council for the divisions of Stadacona in 1861 and La Durantaye in 1864. His friends attributed his failures to his style of campaigning: “He fought strongly and energetically but never engaged in personalities. He discussed political questions before the people as he would have before a meeting of statesmen.” A spirited fighter, Fournier himself thought the explanation lay in the bitter and unscrupulous battle waged against him by the parish priests, the vicar general Charles-Félix Cazeau*, and the electoral machine run by Hector-Louis Langevin*. In any event Fournier was not on the legislative scene during the great debates on Canadian confederation. An unexpected event brought him back into politics. In a by-election in August 1870 he won the seat in the House of Commons for Bellechasse by acclamation. The following year Montmagny elected him to the provincial legislature, as the double mandate allowed. Fournier was one of the Liberal party’s hopes, along with Wilfrid Laurier*.

From 6 July 1871 till 19 Nov. 1873 Fournier, together with Henri-Gustave Joly*, Maurice Laframboise*, and Pierre Bachand*, vigorously opposed the Chauveau government. He attacked on two fronts: bribery in elections and patronage in granting timber limits. His maiden speech was an impassioned denunciation of the bribery that for 20 years had distorted the workings of democracy in the district of Quebec. At every session he and his friends proposed changes to the electoral law, and in 1871 they started a campaign to have controverted elections brought before the courts. His attacks on the friends of the régime who built up lumber empires to the detriment of the public struck a responsive chord among the members of the Legislative Assembly and in the newspapers. The government had to put an end to private sales and cut down on grants of large tracts of land to lumber companies.

In the commons, Fournier had more difficulty at the beginning. During the first year he did not “live up to his reputation,” according to some newspapers. Like many French Canadian members he probably had trouble adapting, and he never stood out in Ottawa as he did at Quebec. He was more of a jurist than a politician, and despite his considerable stature he was perhaps too sensitive and too inflexible to be a leader. He was minister of internal revenue from 7 Nov. 1873 till 7 July 1874, and then minister of justice from 8 July 1874 to 18 May 1875, replacing Antoine-Aimé Dorion, who had been elevated to the bench. Being unable to rally the French Canadian Liberal members around him and having disgraced himself in the eyes of Prime Minister Alexander Mackenzie, as a result of a tavern brawl, he had to hand his portfolio over to Edward Blake* and content himself with that of postmaster general, which he held from 19 May till 7 Oct. 1875, while waiting to be appointed judge.

Fournier was at his best as minister of justice. In 1874 he secured passage of a bill on controverted elections which stipulated that petitions concerning elections should not be heard while parliament was in session. The following year he got a bankruptcy bill passed that required the appointment of trustees and prevented a person from declaring himself bankrupt without having consulted his creditors, who were to retain the initiative in the matter. But his greatest success was the passing on 8 April 1875 of the bill creating the Supreme Court. This legislation, which incorporated the broad principles set out by Sir John A. Macdonald, met the need for a uniform interpretation of the law everywhere in Canada, and for an authority to arbitrate constitutional disputes. There had been a division of opinion on several points, however: whether to put an end to appeals to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council; whether to bring French civil laws under the court’s jurisdiction; and how many judges from the province of Quebec would sit on it. Fournier proved a skilful tactician. With great reluctance he agreed to retain the crown’s prerogative in the appeal to the Privy Council, and he demonstrated that French Canadians had no reason to fear for their laws. British principles of equity were, he declared, identical with those of Quebec’s Civil Code – both legal systems were based upon Roman law. In addition, there would always be more judges from Quebec on the Supreme Court than on the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, where there were none. He had included in the bill stipulations that two members of the province’s bar would sit on the court and that no appeal could be launched in cases from the province involving less than $2,000.

On 8 Oct. 1875 Fournier was appointed to the Supreme Court. He moved his family to Ottawa, but in 1879 his wife died, leaving him with nine children. Adrienne, his eldest daughter, then kept house. Fournier spent winters in Ottawa and summers at Berthier (Berthierville). He took an interest in current affairs, literature, and philosophy. He gave receptions that were much appreciated by educated francophones in Ottawa, and he enjoyed the company of his close friend André-Napoléon Montpetit and the members of the Cercle des Dix, Benjamin Sulte*, Alphonse Lusignan, Joseph-Étienne-Eugène Marmette, Alfred Duclos* De Celles, and other amateurs of the arts. From 1892 to 1895 he was vice-dean of the faculty of law in the University of Ottawa. But for 20 years his main concern was the dispensation of justice. His decisions as a Supreme Court judge, formulated in succinct and precise language, and based on a broad knowledge of the law, bore the mark of a vigorous and penetrating mind. Thibaudeau Rinfret points out that in several cases, especially Attorney General of British Columbia v. Attorney General of Canada (1889) and Canadian Pacific Railway v. Dame Agnes Robinson (1887), his opinion in dissent from that of all his colleagues was vindicated by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. His most famous decisions were: his judgement in Andrew Mercer v. Attorney General of Ontario (1881) [see Andrew Mercer*] to the effect that assets devolving to the crown were not subject to provincial laws, an opinion the Privy Council did not, however, confirm; his ruling in the Manitoba school question, which was upheld by the Privy Council and served in 1896 as the basis for the remedial legislation; and his decision on Ontario’s right to require licences for the manufacture of alcoholic beverages and to draw revenue from them, which was supported by the Privy Council shortly before his death.

Télesphore Fournier died of Bright’s disease on 10 May 1896, at the age of 72 years and 9 months. His friend Montpetit paid tribute to him as “a man of lofty character, of a cultivated, refined mind free from prejudices, of exceptional discernment and uprightness, generous, hospitable, with an iron will tempered, however, by rare kindness and the most exquisite sensitivity.”

ANQ-MBF, CE1-40, 22 juill. 1857. ANQ-Q, CE2-9, 5 août 1823. Can., House of Commons, Debates, 1875; Parl., Sessional papers, 1874. Débats de l’Assemblée législative (M. Hamelin), 1871–72. L’Électeur, 4 nov. 1893, 11 mai 1896. L’Événement, 13 juill. 1871, 16 déc. 1871. Le Journal de Québec, 13, 25, 27 juill. 1854; 19–20 déc. 1857; 22, 25, 28 juin, 2, 6, 11 juill. 1861; 3 juin 1863. Le National (Québec), 20 nov., 7 déc. 1855; 27 août 1857; 12 janv., 28 nov. 1858; 14 juin 1859. L’Opinion publique, 13 juill. 1871. La Patrie, 11 mai 1896. Le Soir (Montréal), 13 mai 1896. “Bâtonniers du barreau de Québec,” BRH, 12 (1906): 342. F.-M. Bibaud, Le panthéon canadien; choix de biographies, Adèle et Victoria Bibaud, édit. (nouv. éd., Montréal, 1891). Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose and Charlesworth), vol.2. Dent, Canadian portrait gallery, vol.3. J. Desjardins, Guide parl. P.-G. Roy, Les juges de la prov. de Québec. RPQ. Réal Bélanger, Wilfrid Laurier; quand la politique devient passion (Québec et Montréal, 1986). Bernard, Les rouges. Creighton, Macdonald, old chieftain. Léon Gérin, Antoine Gérin-Lajoie; la résurrection d’un patriote canadien (Montréal, 1925). M. Hamelin, Premières années du parlementarisme québécois. Rumilly, Hist. de la prov. de Québec, vols.4, 6–7. J. G. Snell and Frederick Vaughan, The Supreme Court of Canada: history of the institution (Toronto, 1985). D. C. Thomson, Alexander Mackenzie, Clear Grit (Toronto, 1960). J.-P. Tremblay, À la recherche de Napoléon Aubin (Québec, 1969). Waite, Canada, 1874–96. Mme Donat Brodeur, “Le Cercle des Dix,” La Rev. moderne (Montréal), 5 (1924), no.10: 19–22. A .[-H.] Gosselin, “Réponses,” BRH, 14 (1908): 320. Charles Langelier, “J.-B. Parkin, c.r.,” BRH, 3 (1897): 82–89. R. O., “Quelques sociétés disparues,” BRH, 49 (1943): 316. “Questions,” BRH, 2 (1896): 128. Thibaudeau Rinfret, “Le juge Télesphore Fournier,” Rev. trimestrielle canadienne (Montréal), 12 (1926): 1–16. P.-G. Roy, “Les sources imprimées de l’histoire du Canada-français,” BRH, 29 (1923): 177.

Cite This Article

Michèle Brassard and Jean Hamelin, “FOURNIER, TÉLESPHORE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 10, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/fournier_telesphore_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/fournier_telesphore_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Michèle Brassard and Jean Hamelin |

| Title of Article: | FOURNIER, TÉLESPHORE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | March 10, 2026 |