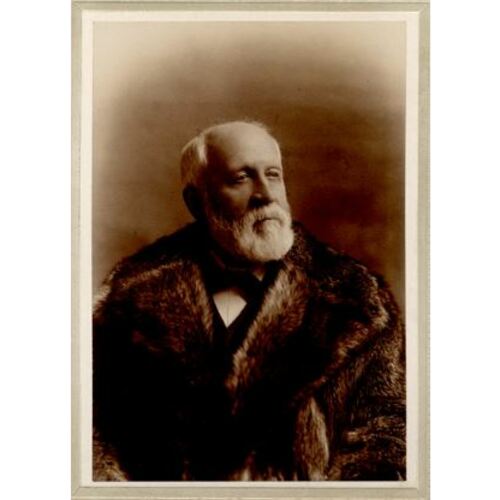

![Marc-Aurèle Plamondon

[Vers 1890]

http://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/3113673 Original title: Marc-Aurèle Plamondon

[Vers 1890]

http://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/3113673](/bioimages/w600.13080.jpg)

Source: Link

PLAMONDON, MARC-AURÈLE, lawyer, journalist, publisher, and judge; b. 16 Oct. 1823 in Saint-Roch ward at Quebec, son of François-Pierre Plamondon and Scholastique-Aimée Mondion; m. 27 Nov. 1849 Mathilde L’Écuyer at Quebec, and they had six children; d. 4 Aug. 1900 in Arthabaskaville (Arthabaska), Que.

Marc-Aurèle Plamondon’s ancestor Philippe Plamondon had come from Clermont, in the Auvergne, France. Born in 1641, he married Marguerite Clément on 23 April 1680 at La Prairie, in New France, and settled in the Quebec region.

Marc-Aurèle studied at the Petit Séminaire de Québec from 1833 to 1842. He became a lawyer on 21 Oct. 1846, having divided his time as a student among law, literature, and journalism. In the periodicals of his day he published odes and songs which were patriotic and romantic in tone. Although of slight literary value, they expressed the concerns of a generation which had lived through the troubles of 1837 and the climate of repression that followed, with the union of the two Canadas. They also bore witness to the continuing presence of France in the intellectual life of French Canada, especially through the influence of its romantic poets.

Trying his hand at journalism, Plamondon worked in 1843 for the Quebec paper Le Canadien, first as a proof-reader and then as a writer for the religious page. He was also the owner of a radical political newspaper in Montreal, L’Artisan, which ceased publication after it was condemned by the church. In 1844 he joined the staff of Le Ménestrel, a literary publication with a music section, and the Courier and Quebec Shipping Gazette, a daily paper for auctioneers and businessmen which was renamed the Commercial Courier/Le Courrier commercial in January 1845 [see Stanislas Drapeau]. In his early writings Plamondon showed an interest in literature and music, as well as a penchant for liberal and democratic views, both of which were to strengthen over time. He was one of the founders of the Institut Canadien of Montreal in 1844, and became its correspondent at Quebec. Four years later he and a group of friends founded the Institut Canadien of Quebec, with Plamondon himself as president. Along with Joseph Papin*, Antoine-Aimé Dorion and his brother Jean-Baptiste-Eric*, Joseph Doutre*, and others with whom he was in regular correspondence, Plamondon denounced various aspects of French Canada’s subservient position. In short, he was of the school of Louis-Joseph Papineau*, and had already joined the Rouges before stepping into the public arena.

According to his contemporaries, Plamondon was made for the lawcourts. His passion, brilliant wit, and natural gift for oratory were to make him an outstanding criminal lawyer, and his name was to be associated with a number of celebrated cases. Journalist Louis-Honoré Fréchette* would later sum him up with a scathing comment instantly qualified: “Many a scoundrel did he send back out into society! By contrast, he has saved many an innocent. . . . I know some he snatched from the hangman by the hair of their heads, so to speak, despite the evidence, the judges, and I dare say, in at least one instance, despite the jury.” Nevertheless Plamondon had a slow start in the legal profession. Like most young lawyers, he had to turn his mind to politics, a realm of even greater interest to him because he wanted to defend and promote liberal principles.

Between 1855 and 1859 Plamondon was both co-owner and co-editor of Le National of Quebec, along with Télesphore Fournier and Pierre-Gabriel Huot. A newspaper engaged in political education, it saw itself as a vehicle for liberal ideas and as a voice for democratic interests. It was “the arsenal which provided the weapons for the fight,” in the words of Liberal Charles Langelier*. The famous trio derived malicious pleasure from confronting any and all rightist views. “It is the ‘National’ which has turned St Roch and the entire Quebec district Liberal,” Langelier was to claim.

Twice in 1857 Plamondon sought a role in politics, running for election to the Legislative Assembly for Quebec City. He put up a bitter struggle, was defeated, and was forced to pull back from the line of fire, but by no means from the political fight. He remained proud of his fidelity to the Liberal party despite his own personal set-backs, and deplored the disloyalty that was all too prevalent in its ranks.

Plamondon’s strong allegiance to the Liberals would win him recognition and an honourable ending to his career. In 1874 Prime Minister Alexander Mackenzie appointed him to the Superior Court as a judge for the district of Arthabaska. Plamondon’s letters suggest that “mounting the bench” changed him very little, even though his official position demanded greater discretion of him. At home, in his “Cabane,” as it amused him to call his imposing house in Arthabaskaville, he was the immediate neighbour of Wilfrid Laurier*. Politics linked him with the Liberal leader as well as with Joseph Lavergne, Lawrence John Cannon, Jules-Adolphe Poisson, Médéric Poisson, and others whom he invited to his conversaziones, joyful gatherings unmarked by care. Arthabaskaville society was known for its passionate interest in politics and love of literature and the arts. Plamondon fitted well in this milieu.

In 1897 he yielded to Laurier’s urgings and resigned as judge to make way for his son-in-law François-Xavier Lemieux*, who had just been denied a place in the provincial cabinet. In so doing, Plamondon smoothed the path for the two newly elected heads of government, Wilfrid Laurier in Ottawa and Félix-Gabriel Marchand in Quebec. The presence in the cabinet of former Liberal radicals such as Lemieux could have posed a threat to the political entente which the Liberal party had made part of its platform and which had been instrumental in securing its recent electoral victories.

Marc-Aurèle Plamondon died three years later, on 4 Aug. 1900, at Arthabaskaville. He was one of the last of the Rouge old guard, and his death heralded the end of an era. The Rouges had left their mark on the political and social history of 19th-century French Canada by their resistance to the tide of conservatism rising even in Liberal circles.

AC, Arthabaska, État civil, Catholiques, Saint-Christophe (Arthabaska), 7 août 1900. ANQ-Q, CE1-1, 27 nov. 1849. Private arch., Andrée Désilets (Sherbrooke, Que.), Fonds M.-A. Plamondon et F.-X. Lemieux, corr.., discours et coupures de journaux. L.-M. Darveau, Nos hommes de lettres (Montréal, 1873). J. Hamelin et al., La presse québécoise, vol.1. Le Jeune, Dictionnaire. Le répertoire national, ou recueil de littérature canadienne, James Huston, compil. (4v., Montréal, 1848–50). P.-G. Roy, Les juges de la prov. de Québec. L.-O. David, Au soir de la vie (Montréal, [1924]). Andrée Désilets, “Une figure politique du 19e siècle, François-Xavier Lemieux” (thèse de des, univ. Laval, Québec, 1964). “Feu l’hon. juge M. A. Plamondon,” Le Soleil, 6 août 1900: 1, 3.

Cite This Article

Andrée Désilets, “PLAMONDON, MARC-AURÈLE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 27, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/plamondon_marc_aurele_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/plamondon_marc_aurele_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Andrée Désilets |

| Title of Article: | PLAMONDON, MARC-AURÈLE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | February 27, 2026 |