Source: Link

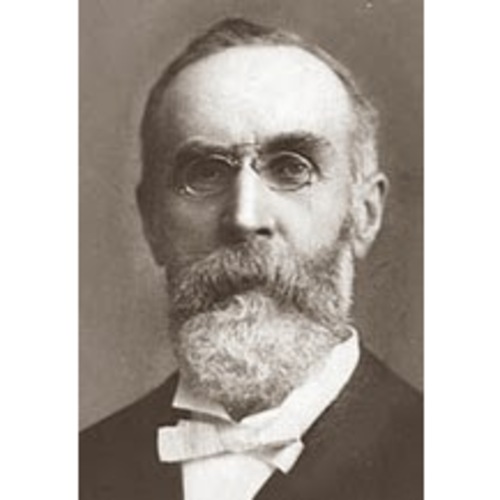

GOODERHAM, GEORGE, businessman and yachtsman; b. 14 March 1830 in Scole, England, third son of William Gooderham* and Harriet Tovell Herring; m. 14 March 1851 Harriet Dean in Toronto, and they had four sons and eight daughters (all but one daughter survived infancy); d. there 1 May 1905.

George Gooderham was born into relative prosperity on the family homestead at Scole, which his father worked as a gentleman farmer. At age two he was among a group of 54 people, led by William Gooderham, who emigrated to Upper Canada. The party arrived at York (Toronto) on 25 July 1832. There the Gooderhams joined James Worts, husband of William’s sister, who had arrived the previous year to establish, for himself and Gooderham, a wind-powered flour-mill at the mouth of the Don River, east of the town. The mill, soon powered by steam and expanded in 1837 to include a distillery, was the engine for the Gooderham fortune in Canada. Worts died in 1834 and in 1845 his son James Gooderham* became a partner in the enterprise, which took the name Gooderham and Worts.

In his youth, George attended Sunday school and became librarian at Trinity Church (Anglican), just north of the family home, which was situated adjacent to the mill-distillery complex. The church (later Little Trinity) became the centre of his early social life. There he met Harriet Dean, whom he married on his 21st birthday. His father, an evangelical Anglican, was a warden of Little Trinity for many years; George was a frequent participant in vestry meetings and was vestry clerk in 1854–55. He rented a pew from 1852 to the 1880s, but in later years he attended St James’ Cathedral.

George entered Gooderham and Worts while young, to learn the trade, and on 1 Aug. 1856 he was made a full partner in the distillery alongside his father and his cousin James. The Monetary Times attributed to his acumen and drive the major expansion of the business begun three years later. “He offered, if permitted a larger share in the concern, to manage the enlargement he had recommended and to take the risk of its success.” The risk of the expansion, completed in 1861 and estimated to have cost $200,000, was reduced through a price-fixing agreement reached sometime before 1861 with rival distiller John H. R. Molson and Brothers of Montreal. By at least 1863 George was superintendent of the Toronto factory.

Gooderham’s rapid rise was partly the result of his elder brothers’ decision to spurn the family’s distilling business. William* had moved to Rochester, N.Y., in 1842 to become a merchant. James, the second-born, joined him at Norval, Upper Canada, in about 1850 to run a general store. In addition to being loyal to the distillery business, George was technically proficient and a perfectionist. “He knew the chemistry of his subject as well as its economy, and was accustomed to make minute tests of grain and of yeast under the microscope,” said the Monetary Times.

The 1859–61 expansion of the business had included installation of automatic milling and distilling machinery. Automation of cooperage operations did not arrive for another decade, when the mechanized methods of making barrels for the oil industry were adopted by the large distilleries. The impact on some 40 coopers at Gooderham and Worts was dramatic: wages and hours at its barrel shops were controlled by the Coopers International Union in 1870 but within two years the union’s grip had been broken by the new machinery. By the mid 1870s the mill’s 150 workers were producing one of every three gallons of proof spirits manufactured in Canada. George Gooderham likely played a large role in the growing efficiency of the distillery throughout this period.

As William Sr expanded into banking and railways, his son followed. In September 1870 George was made a director of the Toronto, Grey and Bruce Railway, which, along with the Toronto and Nipissing Railway, was controlled by Gooderham and Worts and hauled freight for the company. Three years later he was made a director of the Bank of Toronto, also controlled by Gooderham and Worts with his father as president.

William Sr died on 20 Aug. 1881 and his two Gooderham and Worts partnerships – a mercantile business founded in 1846 with J. G. Worts and the distillery – were merged two days later, Worts and George Gooderham becoming sole partners. Most of William’s estate passed to George and William Jr, their brother James having died in 1879. Worts was elected president of the Bank of Toronto (with George as vice-president), but he died on 20 June 1882. The following day George was elected to the presidency, which he held until his death. He also gained control of Gooderham and Worts, and soon applied to parliament to have it transformed into a joint-stock corporation; letters patent were granted on 2 December with capital set at $2 million. Gooderham became president of Gooderham and Worts Limited and his two eldest sons, William George* and Albert Edward*, were appointed directors.

George Gooderham spent much of the remainder of his life broadening the base of his wealth by investing in real estate, mines, and financial services. He eventually held mortgages, worth about $570,000, on 181 Toronto properties, for example, and owned dozens of other city properties, worth an estimated $823,000. With his son-in-law Thomas Gibbs Blackstock, he invested in two world-famous mines, the War Eagle and the Centre Star, in the Kootenay region of British Columbia. As well, he was half-owner of a coalmine in Colorado.

In 1887 Gooderham and other Toronto backers founded twin firms, Manufacturers’ Accident Insurance Company and Manufacturers’ Life Insurance Company, and succeeded in securing Canada’s prime minister, Sir John A. Macdonald*, as president of both. Gooderham, who was a vice-president in each firm, took out the first life-insurance policy, worth $50,000, issued by Manufacturers’ Life. He became president of this company on 22 June 1891, shortly after Macdonald’s death, and oversaw a steady expansion abroad through the 1890s. Gooderham vacated the presidency the day before the firm’s merger on 1 July 1901 with the Temperance and General Life Assurance Company. On 11 April 1900 he had become president of the Canada Permanent and Western Canada Mortgage Corporation (Canada Permanent Mortgage after 1903). This company was the result of a combination of several financial institutions with long-time Gooderham-family backing, including Western Canada Loan and Savings, of which George had been vice-president. He was also president of the Dominion of Canada Guarantee and Accident Insurance Company and a director of the Toronto General Trusts Company, Canada’s first trust company. In addition to managing financial firms, he invested heavily in them. His Bank of Toronto stock grew in value to more than $1 million, for example, and his shares in Canada Permanent were worth more than $300,000 in 1905.

In both distilling and finance, Gooderham’s cautious temperament and attention to detail helped bring success. His greatest talent lay in identifying and exploiting economic linkages. At the distillery, the company controlled more and more stages of production, from the field to the barrel, and profited from such industrial by-products as waste mash, which was fed to the company cattle. In financial services, where Balkanizing legislation limited the activity of each type of institution, Gooderham’s directorships linked a bank, a trust company, a mortgage company, a life-insurance company, and accident-insurance companies. This horizontal integration spread his personal investment risk but, more important, it helped to identify opportunities for profit. Gooderham’s companies thus remained relatively stable during periods of economic turmoil.

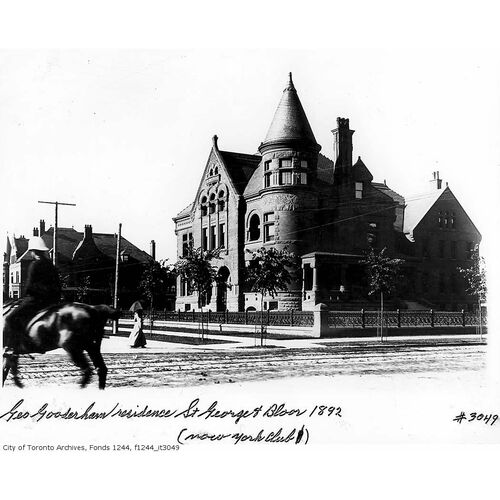

Between 1889 and 1892 Gooderham built an enormous Romanesque-style mansion at the northeast corner of Bloor and St George streets, in Toronto’s newly fashionable Annex neighbourhood. The chief designer was David Roberts Jr, whose father had been architect for the 1859–61 expansion of the mill-distillery complex. Gooderham christened the house Waveney, after the river that flowed past his birthplace in Norfolk. This imposing mansion, which was valued by city assessors at $138,000 and now houses the York Club, was a rare display of wealth from a man who otherwise preferred to stay out of the public eye.

Gooderham’s other great Toronto monuments were his business headquarters – the flat-iron building of 1892 at Front and Wellington, also by Roberts – and the King Edward Hotel on King Street. Designed by Edward James Lennox* and built between 1901 and 1903, the eight-storey hotel quickly ran into serious financing problems. Gooderham, president of the Toronto Hotel Company, which built it, finally agreed personally to post a $1.45-million bond. City boosters praised him for shouldering the risk and giving Toronto a hotel of international standards.

Gooderham indulged a passion for yachting in his later years. In about 1880 he bought the racing schooner Oriole, which he moored at the east end of Toronto Bay by the distillery. It was replaced in 1886 by Oriole II, which won the Royal Canadian Yacht Club’s Prince of Wales Cup in six of the next seven years. Gooderham was vice-commodore of the club from 1884 to 1887 and commodore in 1888. He was also one of six investors in the cutter Canada, which won the first challenge for the Canada Cup, on Lake Erie on 25 Aug. 1896.

In 1881–82 Gooderham built a summer home on Toronto Island, overlooking Lake Ontario and affording a view of RCYC races. He owned an island-ferry service – and, with other ferry owners, sought the permission of city council in late 1886 to operate a monopoly during the summer months. The proposal was withdrawn after a public outcry, and the city eventually launched its own service.

Gooderham held a number of exclusive posts in which he associated with other members of Toronto’s élite. He was at times master of the Toronto Hunt Club, a director of the Ontario Jockey Club, and a captain in the reserve militia. He was also a senator at the University of Toronto and a trustee of the Toronto General Hospital. In the field of music he joined impresario Frederick Herbert Torrington* in organizing two ventures: the Toronto Music Festival (1886), of which he was honorary president, and the Toronto College of Music (incorporated 1890), which he served as president. A Conservative, he donated to the party but never stood for political office.

Chronic bronchitis forced an ageing Gooderham to flee Canada each winter for warmer climates. His condition prompted trips to the Mediterranean and the southern United States. Several weeks after his return from Florida in 1905, he developed pneumonia and died at his Toronto home at age 75.

Gooderham left an estate initially estimated in the press to be worth more than $15 million. “The accumulation of such a fortune in one man’s hands marks an epoch in the development of Canada,” a eulogist wrote in Saturday Night. “That Canada, with her present small population and in her comparatively undeveloped state, should have produced financiers of Mr. Gooderham’s calibre, is remarkable evidence of the enormous possibilities of the country.” His will, made public in August 1905, declared the value of his holdings to be $9.3 million (later revised upward); he was thus one of the richest men in the country. The windfall of $519,000 received by Ontario in succession duties – more than eight per cent of the province’s budget – helped transform a deficit of $480,000 in 1904 into a surplus the following year. The composition of the estate showed how effectively Gooderham had diversified. Almost 90 per cent of his father’s wealth in 1881 had been invested in the distillery; in 1905 Gooderham’s distillery investment represented only about a third of his fortune.

Though he had accumulated seven times the wealth of his father and though his financial and real-estate investments touched the lives of thousands, George Gooderham remained almost unknown, even to his fellow Torontonians. His funeral was small and his legacy was soon dispersed. His will placed the distillery in the hands of his four sons and T. G. Blackstock, the trustees of his estate. The two eldest sons, William and Albert, were to manage the operation and, at the end of ten years, were to be given the right to purchase the business outright. The presidency of Gooderham and Worts passed to William, who held the position until the family’s sale of the distillery in 1923 to Harry C. Hatch*.

ACC, Diocese of Toronto Arch., Toronto, Trinity East (Little Trinity Church), vestry cash-book, 1851–88; vestry minute-books, 1846–1921. AO, F 775, MU 2121, 1887, no.1; RG 22, ser.305, nos.3236, 18190; RG 55, partnership records, York County, declarations, nos.58–59 CP, 2565–67 CP. Ont., Ministry of Consumer and Commercial Relations, Companies branch, Corporate search office (Toronto), Corporation files, C-25036. Toronto-Dominion Bank Arch. (Toronto), Bank of Toronto, annual general meeting of the stockholders, proc., 18 June 1873, 15 June 1881, 21 June 1882, 20 June 1883. Canadian Illustrated News (Hamilton, [Ont.]), 25 April 1863 (supp.). Daily Mail and Empire, 2 May 1905. Evening Telegram (Toronto), 2 May 1905. Globe, 2 May 1905. Monetary Times, 26 Aug. 1881: 287; 5 May 1905: 1480–81. News (Toronto), 2 May, 24 Aug. 1905. Toronto Daily Star, 1–3 May 1905. World (Toronto), 2, 4 May 1905.

G. M. Adam, Toronto, old and new: a memorial volume . . . (Toronto, 1891; repr. 1972). E. [R.] Arthur, Toronto, no mean city, rev. S. A. Otto (3rd ed., Toronto, 1986), 196. Can., Statutes, 1883: cxxviii. Canada, an encyclopædia (Hopkins), 3: 428; 4: 385. Canada Permanent Mortgage Corporation, The Permanent story, 1885–1980, ed. Basil Skodyn (n.p., [ 1980]; copy in AO, Pamphlet Coll., 1980, no.123). Canadian biog. dict. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898). Chadwick, Ontarian families, vol.1. W. A. Craick, “Solidarity of the Gooderhams: industry, thrift and attention to business exemplified,” Maclean’s (Toronto), 27 (November 1913–April 1914), no.4: 5–8, 140–41. William Dendy et al., Toronto observed: its architecture, patrons and history (Toronto, 1986). Sally Gibson, More than an island: a history of the Toronto Island (Toronto, 1984). Illustrated Toronto, past and present, being an historical and descriptive guide-book . . . , comp. J. Timperlake (Toronto, 1877), 244, 271. G. S. Kealey, Toronto workers. Manufacturers’ Life Insurance Company, “and all the past is future” ([Toronto, 1971?]; copy in AO, Pamphlet Coll., 1971, no.89). J. E. Middleton, The municipality of Toronto: a history (3v., Toronto and New York, 1923), 1: 488, 494; 2: 49.Ont., Treasury Dept., Financial statement (Toronto), 1905: 36, 42; 1906: 4–5, 33–35. Saturday Night, 6 May 1905: 2. Joseph Schull, 100 years of banking in Canada: a history of the Toronto-Dominion Bank (Toronto, 1958). Adam Shortt, “History of Canadian currency, banking and exchange: some individual banks,” Canadian Bankers’ Assoc., Journal (Toronto), 13 (1905–6): 184–91. E. B. Shuttleworth, The windmill and its times; a series of articles dealing with the early days of the windmill (Toronto, 1924). C. H. J. Snider, Annals of the Royal Canadian Yacht Club: with a record of the club’s trophies and contests for them (2v., Toronto, 1937–54), 1. Standard dict. of Canadian biog. (Roberts and Tunnell), vol.2. Trinity Church (Little Trinity), 1843–1918 ([Toronto?, 1918?]; copy in AO, Pamphlet Coll., 1918, no.104). S. E. Woods, The Molson saga, 1763–1983 (Toronto and Garden City, N.Y., 1983).

Cite This Article

Dean Beeby, “GOODERHAM, GEORGE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/gooderham_george_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/gooderham_george_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Dean Beeby |

| Title of Article: | GOODERHAM, GEORGE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | March 1, 2026 |