Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

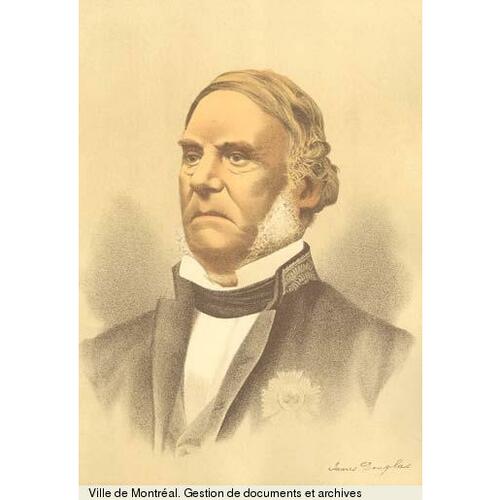

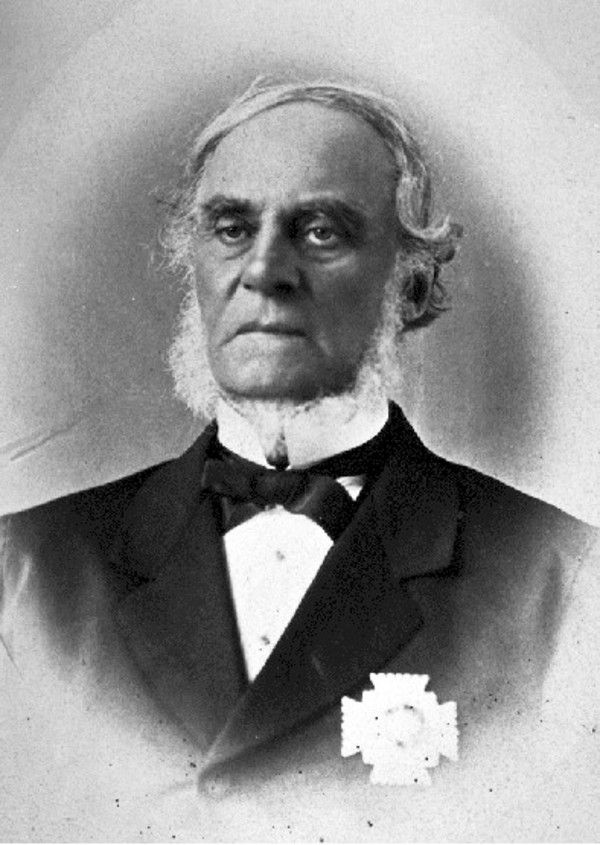

DOUGLAS, Sir JAMES, HBC officer and governor of Vancouver Island and of the crown colony of British Columbia; b. 5 June or 15 Aug. 1803 ; d. at Victoria, B.C., 2 Aug. 1877.

A “Scotch West Indian,” as he was known in the fur trade, James Douglas was the son of John Douglas and nephew of Lieutenant-General Sir Neill Douglas. John Douglas and his three brothers, merchants in Glasgow, held interests in sugar plantations in British Guiana. At Demerara John Douglas seems to have entered into a liaison with a “Creole,” possibly a Miss Ritchie, by whom he had three children, Alexander, b. 1801 or 1802, James, b. 1803, and Cecilia Eliza, b. 1812. John Douglas’ second family were the children of Jessie Hamilton whom he married in Glasgow in 1809. For one of these, Jane Hamilton Douglas, James Douglas developed an affectionate regard.

Placed at an early age in a preparatory school in Scotland, James Douglas learned “to fight [his] own way with all sorts of boys, and to get on by dint of whip and spur.” He received a good education at Lanark, and probably further training from a French Huguenot tutor at Chester, England. During his early years in the fur trade he was singled out for having a sound knowledge of the French language and “possessing a clear and distinct pronunciation.”

At the age of 16 both Alexander and James Douglas were apprenticed to the North West Company. After sailing on 7 May 1819 on the brig Matthews from Liverpool, bound for Quebec, James Douglas proceeded to Fort William, arriving on 6 August. That winter he applied himself to accounting, learning business methods, and studying the Indian character. It is not unlikely that he already displayed those characteristics for which he became noted: industry, punctuality, observance of the smallest detail, and a determination amidst the most pressing business to acquire knowledge of literature and history, politics and public affairs.

In the summer of 1820 he was transferred to Île-à-la-Crosse. There he threw himself into the struggle between the North Westers and the Hudson’s Bay Company men, fighting a duel with Patrick Cunningham and engaging in military manoeuvres and threatening appearances. He was one of four Nor’Westers specifically warned on 12 April 1821 to desist from parading within gunshot of the neighbouring HBC post with “Guns, Swords, Flags, Drums, Fifes, etc., etc.”

On the union of the two companies in 1821, Douglas entered the employ of the HBC as a second class clerk. In 1822, though only 18 years old, he was regarded as “a very sensible young man” and a good Indian trader, who could be trusted to take charge that summer of the Island Lake post.

On 15 April 1825, Douglas left Île-à-la-Crosse by way of Lake Athabasca to take charge of Fort Vermilion in Peace River during the summer. He wintered at McLeod’s Lake on the east side of the Rocky Mountains with John Tod*. The next spring he was at Fort St James, Stuart Lake, headquarters of the New Caledonia district. Douglas had now completed the first of seven crossings of the Rocky Mountains, and the experience had left an imperishable memory “of fresh scenes, of perilous travel, of fatigue, excitement and of adventures by mountain and flood.”

That spring (1826) he visited the Pacific seaboard for the first time. It had been decided to supply New Caledonia from Fort Vancouver, built in 1824 on the north bank of the Columbia River, and to ship its returns round Cape Horn to England. Chief Factor William Connolly*, finding Douglas a “Fine steady active fellow good clerk & Trader, well adapted for a new country,” chose him to assist in opening the overland brigade route for pack-horses from Fort Alexandria on the upper Fraser to Fort Okanagan at the junction of the Okanogan and Columbia rivers. The brigade left Stuart Lake on 5 May, and, travelling 1,000 miles, reached Fort Vancouver on 16 June. With the outfit in nine boats, Connolly started the return journey on 5 July. Douglas, who had been sent with John Work* and Archibald McDonald* to obtain horses from the Nez Percés Indians, joined him at Fort Okanagan. They arrived back at Fort St James on 23 September. In October Douglas was sent on a trading mission to the Secanni Indians, and with its success he was dispatched on 15 May 1827 to establish Fort Connolly on Bear Lake.

During the winter of 1827, at Fort St James, Douglas decided to retire from the fur trade at the end of his three-year contract. By March 1828, discouraged by the isolation of his life, the lack of companionship and of good books, the hostility of the Indians, and the danger of starvation after the salmon run failed, he was “bent on leaving the country.” His employers, however, were willing to renew his contract and increase his salary from £60 to £100.

On 27 April, according to the custom of the country (confirmed in a Church of England ceremony at Fort Vancouver in 1837), Douglas took Amelia Connolly, half-Indian daughter of the chief factor, as his wife.

During the time Connolly left him in charge of Fort St James while he himself took out the 1828 returns to Fort Vancouver, a “tumult” with the Indians erupted. Following the execution of an Indian who had been involved in a murder at Fort George in 1823, Carriers invaded the fort to avenge his death and threaten Douglas’ life. James Douglas could be “furiously violent when aroused,” and the Indians had taken an inveterate dislike to him. In November he was again assaulted, near Fraser Lake. There was further trouble at Fort St James on New Year’s Day, 1829. “Douglas’s life is much exposed among these Carriers,” Connolly reported to Governor George Simpson* in February 1829, “he would readily face a hundred of them, but he does not much like the idea of being assassinated.”

Connolly’s recommendation that Douglas be transferred to Fort Vancouver, where extensive coastal trading and farming operations were under way, was accepted by the Council of the Northern Department. On 30 Jan. 1830 Douglas left Stuart Lake to become accountant under Dr John McLoughlin*, superintendent of the vast Columbia Department.

“James Douglas is at Vancouver and is rising fast in favour,” a fur-trader reported in 1831. Simpson, who had met Douglas at Île-à-la-Crosse in 1822 and at Fort St James in 1828, was convinced that Douglas “is a likely man to fill a place at our Council board in course of time.” McLoughlin entrusted him in 1832 and 1833 with taking the accounts to York Factory. In 1835, as McLoughlin’s chief assistant, he attended the council meeting at Red River Settlement. There, on 3 June, he was given his commission as chief trader. During McLoughlin’s absence in England in 1838–39, Douglas had charge of Fort Vancouver, the coastal posts, the trapping expeditions, and the shipping. Finally, in November 1839, he was advanced to chief factor.

Douglas’ promotion gave him financial security. As chief trader he had earned 1/85 of the company’s net profits, about £400 annually. As chief factor he was entitled to 2/85. Totally dependent on his salary, he practised frugality. As a young clerk earning £60 a year, he had put aside half that amount; as chief trader in 1835, when he received £406 in annual dividends, he kept his expenses at a little over £30. That year he began to support his sister Cecilia, and pay his mite to charity – the Bible Society and the Christian missions in Oregon. By the spring of 1850 he had accumulated savings of nearly £5000.

As the officer responsible in McLoughlin’s absence for the Columbia headquarters, Douglas sought to elevate moral standards. He was disturbed by the presence of slavery. “With the Natives, I have hitherto endeavoured to discourage the practice by the exertion of moral influence alone,” he informed the company in London. “Against our own people I took a more active part, and denounced slavery as a state contrary to law; tendering to all unfortunate persons held as slaves, by British subjects, the fullest protection in the enjoyment of their natural rights.” In 1849 he ransomed a slave with goods worth 14 shillings. He entrusted the moral and religious improvement “of our own little community” to the fort’s Church of England chaplain, but his support was withdrawn when the Reverend Herbert Beaver proved to be a religious fanatic. “A clergyman in this country must quit the closet & live a life of beneficent activity, devoted to the support of principles, rather than of forms; he must shun discord, avoid uncharitable feelings, temper zeal with discretion, [and] illustrate precept by example.” These standards of behaviour had, in fact, become his own.

During this period, when McLoughlin was working to eliminate American competition on the northwest coast and Simpson was expanding the company’s activities in the whole Pacific area, Douglas was adjudged the most reliable man for important missions. In April 1840 he was sent north to Sitka, where he was received with “the most polite attention” by the Russian authorities and where he arranged to take over Stikine under the agreement of 1839 with the Russian American Company. He also selected the site for, and commenced building, Fort Taku in Alaska. In December he went to California to investigate trade prospects, buy cattle, and negotiate with the Mexican authorities for the opening of trade with California. On his advice, the HBC built the post of Yerba Buena at San Francisco.

On these delicate missions, Douglas displayed his talent as negotiator. Like Simpson, he had learned to take the measure of a man with whom he dealt; like McLoughlin, he presented a dignified and self-confident appearance. No detail of government policy, business practice, or social value escaped his attention. The officers and men of the Russian American Company lived in what he considered idleness, and the naval officers employed by the company were “the most unqualified men to manage commercial undertakings.” In Spanish California, in contrast to John Bull’s territories, he found the government arbitrary and the law feebly administered.

At Sitka, treating the Russian governor with firmness, tact, and concession, Douglas negotiated the boundary between Russian and British posts. In their daily conferences he spoke “in a frank and open manner so as to dissipate all semblance of reserve and establish our intercourse on a basis of mutual confidence.” For the Indian trade he obtained an equal tariff at every post. Implementing the 1839 agreement, Douglas promised to supply articles needed by the Russians in this trade, and a quantity of butter and other provisions from Fort Langley. “Honesty is found to be in all cases ultimately the best policy,” he wrote, “but in our intercourse with our Russian neighbours, it will be found so from the first day to the last of our intercourse.”

In California, Douglas found himself received “with a sort of reserved courtesy” by Governor Juan B. Alvarado. His first impulse was to resent such behaviour, but knowing that “second thoughts are best,” he restrained himself and, again making concessions, succeeded in obtaining permission for trapping expeditions, commercial rights, and the right to purchase at a fair price sheep and cattle needed for the HBC farms on the Columbia.

In August 1841 Douglas welcomed Simpson to Fort Vancouver in the absence of McLoughlin and travelled with him to Sitka to negotiate once more with the Russians. Simpson arrived at decisions which were to anger McLoughlin: the far northern posts were to be abandoned, the trading operations of the steamboat Beaver expanded, and a new port was to be established at the southern end of Vancouver Island. Douglas made a reconnaissance of the tip of Vancouver Island in July 1842 and in March 1843 started the construction of Fort Victoria.

The building of Fort Victoria signalled the approach of the last great days of the Columbia District. Though Americans and Britons had enjoyed equal rights west of the mountains since 1827, the great company had virtually eliminated competition in the fur trade between 54°40´ and 42°. Its provisions contract with the Russians, however, had necessitated diversification of operations. Farming at Fort Vancouver and in the Cowlitz Valley had been expanded, and settlers brought in from Red River. In the 1840s American settlers began to trickle into the area, and in 1843 people, according to Douglas “of a class hostile to British interests,” arrived in such numbers that a provisional government was set up in Oregon. Faced with the presence of the American immigrants led into the Willamette Valley in 1842 by Dr Elijah White and by the arrival in 1843 of 120 wagon-loads of settlers, McLoughlin made a virtue of necessity. The new settlers were well armed but they lacked money and supplies. McLoughlin provided seeds and other necessities, and also extended credit at the company’s stores.

Douglas knew that McLoughlin and Simpson were now moving towards a complete break in their personal relations. He remained loyal to the doctor. He agreed with McLoughlin that the Americans might be induced to move to California, but he was alarmed at the sacrifice of the company’s commercial rights, and was convinced that American pressure would increase. He viewed with grave concern the interest of the United States government in additional good ports on the Pacific coast. “An American population will never willingly submit to British domination,” he wrote to Simpson, “and it would be ruinous and hopeless to enforce obedience, on a disaffected people; our Government would not attempt it, and the consequence will be the accession of a new State to the Union.” If the United States gained an advantage on the coast, “Every sea port will be converted into a naval arsenal and the Pacific covered with swarms of Privateers, to the destruction of British commerce in those seas.”

As American immigration swelled the white population in Oregon to 6,000 in 1845, the provisional government extended its jurisdiction north of the Columbia River. The British government showed little concern about defending its claim to the river. With foresight, Douglas put forward the idea of “possessory rights” to permit the company to occupy its posts and farms north of the river, should British territorial claims be surrendered.

In 1845 the company, recognizing that the situation in Oregon had reached a critical stage, replaced McLoughlin’s rule with a board of management consisting of Dr McLoughlin, Peter Skene Ogden*, and James Douglas. On McLoughlin’s retirement in 1846, Douglas was selected as the senior member, and John Work was added. McLoughlin and Douglas would now go their separate ways: McLoughlin had decided to throw in his lot with the Americans; without wavering for a moment, Douglas remained loyal to the company and to Britain.

When, in 1846, the British government relinquished its claims to the north bank of the Columbia River and accepted the 49th parallel as the boundary, Douglas reorganized the brigade routes from New Caledonia to make them converge at Fort Langley on the lower Fraser River. In 1848 he investigated the market at Honolulu for salmon and lumber. At last, in 1849, he moved the company’s headquarters, shipping depot, and provisioning centre from the Columbia to Fort Victoria.

To prevent American expansion northward, the company on 13 Jan. 1849 accepted a royal grant to Vancouver Island for ten years. A colony was to be set up within five years, and Douglas expected to be chosen governor of “the real ultima thule of the British Empire.” But to avert “the jealousy of some parties, and the interested motives of others,” he was passed over in favour of Richard Blanshard*. Preparations for the governor, the colonists, and the farm bailiffs sent from England were incomplete when Blanshard arrived at Fort Victoria in March 1850. Workmen were deserting for the California goldfields. “The affairs of our nascent Colony on Vancouver’s Island are not making much progress,” Douglas admitted in November. Blanshard had already sent in his resignation. Awaiting its acceptance, the governor became attentive to complaints that too much power was vested in Douglas, that land prices were too high, and that prices at the company store were exorbitant. Settlement was so impeded by the selective immigration policy of the Colonial Office that when Blanshard set up a council on 27 Aug. 1851, he was forced to appoint Douglas and Tod, company men, and Captain James Cooper, a former HBC employee.

On 16 May 1851 Douglas had been appointed governor and vice-admiral of Vancouver Island and its dependencies. The news did not reach him until 30 October. “I am again appointed Governor pro tempore” he had complained on Blanshard’s departure in September, “this is too much of a good thing. I am getting tired of Vancouver’s Island.” His appointment confirmed, however, he entered into his dual capacity of governor and chief factor with enthusiasm. The gold discovered on Queen Charlotte Islands was protected from the American grasp, the company was advised to purchase the Nanaimo coalfield, Indian lands near Fort Victoria were bought and reserves laid out, roads were built, and schools established.

No matter concerned Douglas more than Indian policy. Towards the Indians, his attitude was one of benevolent paternalism, though he followed the HBC rule that outrages must be speedily punished. To hunt a Cowichan murderer in 1853, he organized among the company servants the Victoria Voltigeurs – a small group of volunteer militiamen – enlisted the services of the Royal Navy, and, for the trial, empanelled a jury on board the Beaver. The same year he had the bastion built at Nanaimo.

In laying out reserves, he left the choice of the land and the size to the Indians. Surveyors were instructed to meet their wishes and “to include in each reserve the permanent Village sites, the fishing stations, and Burial grounds, cultivated land and all the favorite resorts of the Tribes, and in short to include every piece of ground to which they had acquired an equitable title through continuous occupation, tillage or other investment of their labour.” At first the Indians’ requests were moderate, not exceeding ten acres per family, but later in the pastoral country in the interior, where they needed range land for their cattle and horses, the reserves were much larger. Title” “remained vested in the crown “as a safeguard and protection to these Indian Communities who might, in their primal state of ignorance and natural improvidence, have made away with the land.” As his total land policy evolved, Douglas, certain that the time would arrive “when they might aspire to a higher rank in the social scale and feel the essential wants of and claims of a better condition,” permitted the Indians as individuals to acquire property by direct purchase from government officers or through pre-emption, “on precisely the same terms and considerations in all respects, as other classes of Her Majesty’s subjects.”

As senior company officer west of the mountains, Douglas encouraged the traders at Fort Langley to supplement fur exports with farm produce and other commodities. Knowing that the innovations on Vancouver Island would in time destroy the fur trade, he jealously guarded the company’s rights in New Caledonia, on the mainland. He scrutinized the company’s civil and military expenditures in the island colony, and paid into a trust fund all revenues from sales of land, timber, and mines.

In his new authority as governor, he experienced resentment. Colonists expected more than he could provide in the way of improvements, and accused him, when he appointed two old associates to the council, of desiring oligarchic control. In 1853 his old friends, Tod, Dr William Fraser Tolmie*, and Roderick Finlayson*, influenced by the views of Captain Cooper, the Reverend Robert J. Staines*, company chaplain, and Edward E. Langford*, farm bailiff, permitted representations against him to be made to a visiting English mp, C. W. Wentworth-Fitzwilliam. At Lachine, Sir George Simpson, hearing complaints about neglect of the fur trade from Tod and Ogden, questioned his loyalty to the company, and spread a report that Douglas was “always personally vain and ambitious of late years. His advancement to the prominent position he now fills, has, I understand, rendered him imperious in his bearing towards his colleagues and subordinates – assuming the Governor not only in tone but issuing orders which no one is allowed to question.” “Douglas appears anxious to keep us in the dark relative to affairs in Vancouver Island,” Ogden informed Simpson. “From what I can learn some of the Settlers say Cooper and Tod speak the words of truth which he does not find very palatable and very soon the Fur Trade will find an advocate to speak the truth also. The present system will never answer, too much power placed in the hands of one Man must and will cause a clashing of Interests . . . .”

Settlers like Cooper claimed that neither the company nor Douglas had carried out the obligation to settle the island. They demanded that the colony revert to the crown and a governor be chosen who would be independent of the company and who would not rely on company officers for advice and the enforcement of governmental policies.

The basic grievance, Douglas felt, was the land policy. Neither the company nor the Colonial Office had accepted his advice that free grants of 200 or 300 acres be allowed. Instead, the price of land was set at £1 an acre, the minimum holding was 20 acres, and settlers who bought 100 acres were required to bring out labourers. In addition, the company, by setting aside an HBC reserve of nearly six square miles near the fort, and by locating its farms in the other good agricultural areas, had caused the settlers to disperse to inferior farming districts.

Douglas himself was convinced that a settlement was being effected and that the colony had a future. Though other company men were, he said, “scared at the high price charged,” he commenced in December 1851 to purchase land at the regular price as an investment. To 12 acres he acquired adjacent to the fort, he soon added other properties: at Esquimalt, 418 acres in 1852, 247 acres in 1855, and 240 acres in 1858. At Metchosin he bought 319 acres. His most valuable properties were at Victoria – Fairfield Farm and a large holding at James Bay adjoining the government reserve.

Memorials prepared in the colony in 1854 were brought before both houses of parliament through Fitzwilliam’s efforts. To previous complaints was added the charge of nepotism – Governor Douglas, having found his magistrates, E. E. Langford, Thomas Blinkhorn, Kenneth McKenzie, and Thomas James Skinner, ignorant and unreliable, had appointed David Cameron, who arrived from Demerara in 1853 with his wife Cecilia Eliza Douglas Cowan, to the position of chief justice of the new Supreme Court of Justice.

Before parliament made any decision about renewing the monopolistic trading rights on the Pacific slope granted to the company for 21 years in 1838, it would have to examine its record. Its performance as colonizing agent would also be assessed. In the interval, the Colonial Office retained Douglas in his position, but curtailed his executive power. On 22 May 1856 he was ordered to establish an assembly. He complied, though, as he said, he had “a very slender knowledge of legislation, and was without legal advice or intelligent assistance of any kind.”

A fur preserve boasting a single stockaded fort only a few years before, Vancouver Island was now a colony with limited representative government. Compared with neighbouring Washington Territory where land was free, the colony’s population was small, but it lived in peace without Indian warfare. Through Douglas’ efforts, large-scale farming, saw-milling, coal-mining, and salmon fishing had been established. He had plans for government buildings for his diminutive capital, and was endeavouring to have Esquimalt become a naval base. His accomplishments offset the criticism of his rule by Blanshard, Cooper, and Admiral Fairfax Moresby before the select committee of the British House of Commons in 1857. When the government converted Vancouver Island into a crown colony in 1859, the governor it chose was James Douglas. It was already known in London in 1857 that gold had been discovered on the mainland, still under HBC control. A colonial officer of Douglas’ experience would be a good man to have standing by.

In July 1857 Douglas had reported to London that Americans were mining on the Thompson River and an officer was needed to maintain law and order. By December a rush impended. Left without instructions, he seized the initiative as he had done at the time of the Queen Charlotte Islands’ gold discovery. As the nearest representative of British authority, on 28 Dec. 1857 he proclaimed the crown’s control of mineral rights and required miners to take out licences. He was still without instructions when the first shipload of California miners landed at Victoria on 25 April 1858. “If the Country be thrown open to indiscriminate immigration, the interests of the empire may suffer,” he warned London. Equally concerned about the company’s private trading rights, he enlisted the aid of Captain James Charles Prevost of the British Boundary Commission, and had him station his gunboat at the mouth of the Fraser to collect licences from all ships and boats entering the river.

Once before Douglas had experienced the results of American penetration. Now he saw danger of repetition of the Oregon story. American squatters were on San Juan Island, close to Victoria and the sandheads of the Fraser River, and 8,000 miners had travelled the old brigade trail up the Okanagan valley. The English hamlet of Victoria, transformed into a tent-city, was filled with American merchants, brokers and jobbers, land agents, and speculators. In the wild and empty country across the Gulf of Georgia, foreign prospectors had made the Indians restive and were threatening to take the law into their own hands. As Douglas saw it, Victoria, rather than San Francisco, must become the supply centre for the mines; the Fraser, rather than the Columbia, the artery of commerce and traffic. To protect British sovereignty, a military and a naval force were needed. The British rule of law would have to be imposed on “the lawless crowds.”

Twice during the summer of 1858 he visited the diggings. Some miners, discouraged by the high waters of the spring freshet, had already abandoned the river-bars and left the country. But between Fort Langley and Fort Yale over 10,000 men were panning gold. A few had pushed along the precipitous river banks beyond Yale and the big canyon to Lytton. River transportation and roads were required. So were mining regulations and policing. In July Douglas permitted two American stern-wheelers to supplement the company boats on the navigable 100 miles to Yale. Volunteers were called for to build a road by the Harrison River route to Lillooet and a mule track from Yale to Lytton. Mining regulations were drawn up, constables were hired, and Indians were appointed as magistrates to bring forward natives who broke the law. To prevent squatting Douglas had townsites surveyed near the company posts at Langley and Hope and lots were offered for sale.

“I spoke with great plainness of speech to the white miners who were nearly all foreigners representing almost every nation in Europe,” he reported to the Colonial Office on 15 June 1858 after his first visit to the goldfields. “I refused to grant them any rights of occupation to the soil and told them distinctly that Her Majesty’s Government ignored their very existence in that part of the country, which was not open for the purpose of settlement, and they were permitted to remain there merely on sufferance, that no abuses would be tolerated, and that the Laws would protect the rights of the Indians no less than those of the white men.”

After his authority had been confirmed in August he vested title to land in the crown. It was opened to settlement slowly, and, in the hope of attracting British immigrants, it was priced low. Only British subjects could purchase land, but all those who applied for naturalization could obtain it.

Douglas’ initiative had at first aroused enthusiasm in London. Then a new colonial secretary, Sir Edward Bulwer-Lytton, a severe critic of the HBC monopoly, read into his preliminary measures an intention to keep the whole trade of the country for “the HBCo’s people as far as possible.” He reprimanded Douglas, then took steps to terminate the company’s rights and to open the Pacific slope to settlement. On 2 Aug. 1858 parliament, on his advice, converted the territory of New Caledonia into the crown colony of British Columbia.

Douglas was offered the governorship of the new colony on condition that he sever his connection with his old company. In Simpson’s opinion, he was unquestionably the best man for the office, and his salary would help “to carry him through his difficulties, aided by personal vanity of which he has a fair store combined however with a good deal of determination and tact.” The two interests Douglas represented had become antagonistic, and although there would be general regret at his quitting his old concern, his “ostentatious style of living” as governor and his liberality in entertaining all comers had been saddled on the fur trade “whose interests benefitted very little by it.”

The salary offered Douglas as dual governor was only £1,800, but he obtained solace from a Companionship of the Order of the Bath, conferred for his administration of the company-sponsored colony of Vancouver Island. At Fort Langley on 19 Nov. 1858, divested of his commission and supposedly of his interests in the HBC, James Douglas, cb, took the oath of office as governor of British Columbia.

By the spring of 1859 Douglas had not succeeded in persuading the company to purchase his retiring rights. The company was pressing its own claims for compensation for expenditures in the colony of Vancouver Island, and its headquarters was disturbed by reports from Alexander G. Dallas* in Victoria who was investigating Douglas’ accounts. Instances had been found when “fur trade” funds had been used for colonial purposes. In addition, £17,000 had been taken from the fur trade account in 1858 “under the pressure of the moment” to buy provisions for the miners flocking into British Columbia. Simpson confided in Dallas that “the conviction has been most unwillingly forced upon me, that Mr. Douglas has been making an unjustifiable use of the authority with which he is invested for the promotion of his private interests and the benefit of his Family and retainers. . . . I presume there will be difficulty in putting a detainer on his funds in the Company’s hands; but his retired interest is under their control, and I think it might very fairly be held in suspense until the Colonial account is settled.” The company shared this view. No action was taken when in May 1859 Douglas tendered his rights for the sum of £3,500.

His legitimate expectations destroyed, and his salary as governor inadequate, Douglas threatened to resign. “As a private individual I can live in a style befitting the fortune I possess,” he informed the Colonial Office, “but as Governor for the Crown there is no choice, one must live in a manner becoming the representative of the Crown.” Though the government regarded him as the indispensable man, all it would give was a vague promise that his salary would be augmented as proceeds from land sales in British Columbia increased.

Until the crown decided to establish a legislature in British Columbia, absolute power had been given to the governor to administer justice and to establish laws and ordinances. It would not be fair to the grand principle of free institutions, Lytton had declared in July 1858, “to risk at once the experiment of self-government among settlers so wild, so miscellaneous, and perhaps so transitory, and in a form of society so crude.” The plan satisfied Douglas, who believed that “the best form of government, if attainable, is that of a wise and good despotism,” and that “representative Governments cannot be carried on without recourse directly or indirectly to bribery and corrupting influences.” He took the opportunity to determine policy and announce it in the form of proclamations.

Because the gold colony was richly endowed by nature, the British government, other than bearing military costs, intended only to provide a tiny civil list for a judge and a few officials. It did instruct Rear-Admiral Robert Lambert Baynes of the Pacific fleet to assist Douglas, but his flagship, the 84-gun Ganges, did not reach Esquimalt until October 1858, after most of the miners had left to winter in California. In February 1859 a frigate and a corvette with 164 supernumerary marines arrived from the China waters. A detachment of 165 Royal Engineers was also sent from England; the main body arrived in April 1859.

During the critical period of the first mining season there had thus been neither civil power nor military aid. Unarmed with political authority, Douglas was accompanied only by a bodyguard of 20 sailors and 16 Royal Engineers seconded from the boundary commission when in August 1858 he had made his sortie to the mining camps to suppress disorder and announce his intention to consolidate the goldfields as an integral part of the British empire. He wrote to Herman Merivale on 29 Oct. 1858 that he had never before seen “a crowd of more ruffianly looking men,” but at his command they gave three cheers, “with a bad grace,” for the queen.

Nothing like the 1858 influx of 25,000 prospectors occurred in 1859. Some of the miners preferred the freer atmosphere of the American mining-fields; others followed rumours of fresh finds on American soil. The Royal Engineers, sent to plan a communications system, survey town-sites, and provide military protection, could concentrate on these tasks. Colonel Richard Clement Moody*, officer commanding the troops and commissioner of lands and works, selected, with defence against the Americans in mind, a site near the mouth of the Fraser River for a colonial capital, later called New Westminster. The sappers and the marines were put to work to cut down the giant timbers on the steep hillside.

The governor, too, was concerned about security. When an American military force landed on San Juan Island on 27 July, it took both the Legislative Assembly of Vancouver Island and Rear-Admiral Baynes to restrain him from using force to expel it. Until its sovereignty could be decided, the island was put under joint military occupation. When he heard of the Trent incident in 1861, Douglas longed to use the naval force in the north Pacific, the Royal Engineers, and the Royal Marines stationed on San Juan Island to seize San Juan, take possession of Puget Sound, and push overland to the Columbia: “With Puget Sound, and the line of the Columbia in our hands, we should hold the only navigable outlets of the country – command its trade, and soon compel it to submit to Her Majesty’s rule.” To his disappointment a damper was put on this proposal by the British government.

In 1860 the provisioning of the inland mines became an acute problem. To encourage importers, Victoria was declared a free port, and, to stimulate farming in the interior, a pre-emption system was introduced. When rich strikes were made at distant Antler Creek in 1860, it became evident another rush was impending. Wagon-trains would have to replace pack-trains, and the cost of transporting goods through the rugged mountain passes would have to be reduced. For improving roads Douglas employed civilians as well as sappers, and when the British government refused financial assistance, he raised funds by tonnage duties, road tolls, mining licences, and, in 1861, a bank loan of £50,000.

In 1862 the Cariboo goldrush attracted 5,000 miners. On this occasion, Governor Douglas produced his plan for a major wagon road, 18 feet wide, to run 400 miles from Yale, beyond the river’s gorge northward to Quesnel, and eastward to Williams Creek. The Great North Road, to be built by Royal Engineers and civilian contractors, was to end the threat of American economic domination by making the Fraser River, despite its obstacles, the commercial and arterial highway of British Columbia. He hoped that the road could be extended to link British Columbia with Canada. “Who can foresee what the next ten years may bring forth,” he wrote in 1863, “an overland Telegraph, surely, and a Railroad on British Territory, probably, the whole way from the Gulf of Georgia to the Atlantic.”

Since the discovery of the first heavy gold nuggets at Williams Creek in Cariboo in 1861, the population had changed. On his visits in 1862 to Barkerville and the other towns along the creek, it seemed to Chief Justice Matthew Baillie Begbie*, the stern and haughty judge sent from England, “as though every good family of the east and of Great Britain had sent the best son they possessed for the development of the gold mines of Cariboo.” In the overland party from Canada in 1862 were farmers who intended to reside permanently in the colony. At last there was that infusion of “the British element” so much desired by Douglas.

New Westminster, the gold colony’s capital city, already had its full complement of Canadians. Many of them were merchants and speculators who became malcontents as their hopes for prosperity dwindled. Business languished in New Westminster with Victoria emerging as the commercial and banking centre, and with Yale becoming the river-landing for transshipment to the inland mines. A bitter jealousy of the island colony developed, and Douglas came under criticism for continuing to reside, along with his officials, at Victoria. His unpopularity grew as he became increasingly dependent on assistants sent from England and as John Robson*, the fiery editor of the British Columbian, disseminated evidence of his authoritarianism.

To the first request for popular government at New Westminster, Douglas had responded by granting on 16 July 1860 incorporation as a city and the election of a municipal council. In forwarding the demand for an assembly made in 1860 he had expressed the opinion that the British element in the gold colony was still too small to justify this concession. Four later memorials requesting popular government were forwarded to the Colonial Office; three of these remained unacknowledged by the Duke of Newcastle [Henry Pelham Clinton].

The calling of a convention at Hope in September 1861 to demand responsible government aroused the governor’s ire: “The term is associated with revolution and holds out a menace – the subject has an undoubted right to petition his sovereign, but the term ‘convention’ seems something more, it means coercion.” The principle of representative government he recognized: in 1862, anticipating the reorganization of the colony’s government in 1863, for which provision had been made in the founding act, Douglas recommended a small chamber, one-third nominated by the crown and two-thirds elected.

Douglas was aware that “the New Westminster radicals” had enlisted the support of a Canadian politician, Malcolm Cameron, and that Cameron had been applying pressure on Newcastle since 1861 for his removal. After a visit to New Westminster in 1862, Cameron called on Douglas to show him a petition he intended to present to the queen. Douglas dismissed him, curtly informing him that he himself was the proper guardian of the people’s rights and liberties, and that if he could not grant relief, he would lay the grievances “in a proper manner” before her majesty’s government. In reporting the incident to the Colonial Office, he insisted that the community in British Columbia was prosperous and content. “A petty Californian-Canadian clique about New Westminster, the authors of all the clamour about ‘Responsible Government,’ form the only exception. That party is composed of men utterly ignorant of the wants and conditions of the Country; who never have done anything, and never will do anything for it, but complain; and who are, not unjustly, the objects of its derision.”

In London, in February 1863, Cameron presented to the authorities the memorial signed by “certain inhabitants of British Columbia.” “I cannot help thinking,” Newcastle told him, “that they are a little unreasonable in complaining of their appeals for a complete change of their present form of Government . . . They call that form ‘Anti-British’ and ‘anomalous’ but they forget that their Colony is hardly five years old, – that the form was established by Act of Parliament in 1858, and that this year, – 1863 – was fixed in that act as the period at which the question of any change of government should again come under consideration.”

One month later the Duke sent a dispatch to Douglas: “As you have now ruled over Vancouver Island for twelve years – twice the usual period of Governorship – and as I do not think it would be desirable to replace you by a new Governor there and leave you to take up your abode in New Westminster as Governor of British Columbia alone, I intend to relieve you of both Governments. . . . It may be assumed however that I shall not carry out this decision in any way that can be disagreeable to you or shall give a triumph to those who have desired your recall. . . . I have now recommended to the Queen your Successor in the two Governments, and I have accompanied the recommendation with one that you shall be raised to the second rank in the Order of the Bath.”

In order to finance his great arterial highway, Douglas had not waited for formal authorization before borrowing £100,000. On this score he had been criticized in London. Newcastle had learned that somehow Douglas had increased his salary from £1,800 to £3,800. Old and new enemies made in the course of a long career had also turned up at Whitehall; one was Langford who long ago had attacked Douglas for creating on Vancouver Island a “Family-Company Compact”; another was Captain William Driscoll Gosset, an officer in the Royal Engineers who had proved incompetent as treasurer of British Columbia. It was known that Douglas’ relations with Colonel Moody, who with the Royal Engineers was recalled in 1863 from the colony, had not been cordial, and some credence was put in the assertions of the newspaper editors, Amor De Cosmos* in Victoria and John Robson in New Westminster, that he was despotic.

As he prepared to step down from office in the spring of 1864, Sir James Douglas had the satisfaction of knowing that he had ended the alien threat and protected the British foothold on the Pacific seaboard. His road was built, Cariboo was at the height of gold production, towns were laid out in the interior, and law and order prevailed in the mining fields. In 1864 the colonial revenues rose to £110,000; Victoria was a city of 6,000 persons, and Barkerville almost as large. Douglas’ last task for British Columbia, now a stable community, was to set up a legislative council. “Sir James Douglas’s career as governor has been a remarkable one,” an official at the Colonial Office acknowledged. “He now quits his two Govts. leaving them in a state of prosperity, with every prospect of greater advancement.”

To Douglas, it seemed that, whatever the character of his administration, the queen’s grace in knighting him and the honours tendered him by the colonists on his retirement left only one opinion: his driving purpose had been “to promote the public good and to advance the material interests of the colonies.” He continued to urge on Newcastle the building of a practicable road to connect British Columbia and Canada: if this step were taken, “trade would find an outlet, population and settlement would follow.”

During his long service in the fur trade Douglas had never taken a furlough nor been absent one day from duty. As colonial governor, he had dedicated himself to responsibility and toil. His manner was singular and pompous, but he could never consent “to represent her Majesty in a shabby way.” “All people speak with great admiration of the Governor’s intellect – and a remarkable man he must be to be thus fit to govern a Colony,” Sophia Cracroft, the travelling companion of Lady Franklin [Jane Griffin], noted in 1861. “He has read enormously we are told & is in fact a self educated man, to a point very seldom attained. His manner is singular, and you see in it the traces of long residence in an unsettled country, where the white men are rare & the Indians many. There is a gravity, & a something besides, which some might & do mistake for pomposity, but which is the result of long service in the H.B. Co’s service, under the above circumstances. . . .” The governor’s wife they found to be a woman with a gentle, simple, and kindly manner. “Have I explained that her mother was an Indian woman & that she keeps very much (far too much) in the background, indeed it is only lately that she has been persuaded to see visitors, partly because she speaks English with some difficulty, the usual language being either the Indian, or Canadian French wh. is a corrupt dialect.”

The British government allowed Sir James the usual perquisite of office and paid his passage “home.” On 14 May 1864, after welcoming his successors, he set out on a voyage to London. His sickly son James had already been sent home to be educated, and living in Scotland was his daughter Jane, wife of A. G. Dallas. He would also make the acquaintance of his half-sisters and others of his father’s relatives.

Sir James was in Paris in 1865, returning from a grand tour of Europe, when he received news that his daughter Cecilia, wife of Dr John Sebastian Helmcken*, had died. It was the first break in a family circle which had included six children (seven of the 13 children born to Douglas’ wife at a fur trade post had not lived to maturity).

A devoted family man, and one with strong puritanical instincts, Douglas treated his wife with the same respect and affection he had seen Dr McLoughlin display for his half-Indian wife. “I have no objection to your telling the old stories about ‘Hyass’,” he gently reprimanded his youngest child, Martha, “but pray do not tell the world they are Mammas.” Perhaps because of their background, he had watched the development of his children with the greatest solicitude. His son James, too delicate to live long, died in 1883. Of Sir James’ three remaining daughters, Agnes was married to Arthur T. Bushby, an officer in the colonial service of B.C., and Alice to Charles Good, another of the young men who had arrived during the first gold-rush seeking employment. Alice’s marriage, an unhappy one, ended in separation in 1869 and there was a divorce after her father’s death. Martha would eventually marry Dennis Harris.

Except for his grand tour of 1864–65 and another brief trip abroad, Douglas spent his retirement years in Victoria. Martha was the consolation of his last days. He and Lady Douglas could hardly bear to part with her when she was sent to England for schooling in 1872. Martha was to be his “learned daughter – the veritable Bluestocking of the family,” and she responded dutifully to his admonitions: “You have plenty to say, and you must learn to say it well, for that is a necessary accomplishment to young Ladies as to others – therefore study to express your meaning with ease, without prolixity and without Tautology.” “You must be very careful about your personal expenses, studying a proper economy in every way. Sheer extravagance is a sure road to poverty and ruin.”

In his retirement Sir James seldom commented on political affairs to anyone but Martha, or to his sons-in-law, Dr J. S. Helmcken, one of the three delegates who negotiated British Columbia’s entry into confederation, and A. G. Dallas, by this time well known in London financial circles. Bemoaning the union of the seaboard colonies in 1866 and the loss of Victoria’s free port, Douglas inscribed in Martha’s diary: “The Ships of war fired a salute on the occasion – A funeral procession with minute guns would have been more appropriate to the sad melancholy event.” In 1872 he lamented to her: “The Island of San Juan is gone at last. I cannot trust myself to speak about it and will be silent.” “We are now in hourly expectation of hearing how Sir John [Macdonald*’s] Ministry are faring at Ottawa,” he wrote at the time of the Pacific Scandal, “if the want of confidence is carried against him by the Grits, Sir John will have to resign and there will be no end of trouble and delay about the construction of the Railway. The Grits as the opposition faction is termed are a low set and nothing good is to be expected from them.”

His little family, with his respectable connections in England and Scotland, had grown dearer to him with the passing of the years. His visits abroad seemed to increase his determination to leave his children “a competence” so that they could take their place in society. “Friend Douglas . . . ,” old John Tod wrote in 1870, “as he gets older, seems more and more engrossed with the affairs of this world notwithstanding his ample means, he is as eager and grasping after money as ever, and, I am told, at times seized with gloomy apprehensions of dying a beggar at last. . . .” Douglas practised economy to the end of his days: in 1869, when his income from land and investments was $27,300, his expenses were only $5,000. In addition to establishing a trust fund and annuity for Lady Douglas, his will amply provided for his son James, as well as for legacies for his small family circle amounting to nearly $70,000. His valuable properties remained almost intact during Lady Douglas’ lifetime. (Her death occurred on 8 Jan. 1890.)

As the result of a heart attack Sir James Douglas died at Victoria on 2 Aug. 1877. His funeral was public; in Victoria and throughout B.C. there was a great outpouring of grief, affection, and respect for the man who had become known as “The Father of British Columbia.”

A man of iron nerve and physical prowess, great force of character, keen intelligence, and unusual resourcefulness, Douglas had had a notable career in the fur trade. As colonial governor his career was even more distinguished. Against overwhelming odds, with indifferent backing from the British government, the aid of a few Royal Navy ships, and a small force of Royal Engineers, he was able to establish British rule on the Pacific Coast and lay the foundation for Canada’s extension to the Pacific seaboard. Single-handed in the midst of a gold-rush he had forged policies for land, mining, and water rights which were just and endurable. He had kept the respect of the individualistic, competitive, and wasteful miners. His great Cariboo road had served their purpose, but it had served a still greater purpose: it permitted trade and commerce to be kept in British hands and British law and justice to be more easily upheld. As the gold of Cariboo flowed into British coffers, the links with the mother country were strengthened; as travel on the Cariboo road increased, the possibility seemed less remote that transcontinental travel routes could be practicable.

A practical man, but yet a visionary, Sir James Douglas was also humanitarian. He treated individuals, including Negro slaves and Indians, with a respect that few of his contemporaries showed. The majesty of his bearing aroused criticism, but that same bearing made him the symbol, in the motley crowd attracted to the two British seaboard colonies, of the fact that the British presence was firmly established on the northwest coast.

Archives of the ecclesiastical province of British Columbia (Vancouver, B.C.), George Hills diary, 27 June 1838–17 Nov. 1895. Gregg M. Sinclair Library, University of Hawaii, Hawaiian coll., Sophia Cracroft journal, 15 Feb.–3 April 1861. HBC Arch. A.7/2 (London locked private letter book, 1823–70); A.8/8; B.89/a, B.89/b, B.223/b, B.226/a, B.226/b, B.226/c; D.5/30, D.5/32, D.5/36 (George Simpson, Correspondence inward, 1822–60). PABC, Fort Vancouver, Correspondence outward to HBC, 1832–49 (letter book copies); Fort Vancouver, Correspondence outward, 1840–41 (letter book copies); Fort Victoria, Correspondence outward to HBC, 1850–55, 1855–59 (letter book copies); Vancouver Island, Governors Richard Blanshard and James Douglas, Correspondence outward, 22 June 1850–5 March 1859 (letter book copies); Vancouver Island, Governor James Douglas, Correspondence outward, 27 May 1859–9 Jan. 1864 (letter book copies); British Columbia, Governor James Douglas, Correspondence outward, 27 May 1859–9 Jan. 1864 (letter book copies); Governor James Douglas, Dispatches to London, 1851–55, 1855–59 (letter book copies); Governor James Douglas, Correspondence inward, 1830–68; James Douglas, Account and correspondence book, 1825–72; James Douglas, Correspondence outward, private, 22 May 1867–11 Oct. 1870 (letter book copies); James Douglas, Diary of a trip to the northwest coast, 22 April–2 Oct. 1840; James Douglas, Diary of a trip to California, 2 Dec. 1840–23 Jan. 1841; James Douglas, Diary of a trip to Sitka, 6 Oct.–21 Oct. 1841; James Douglas, Diary of a trip to Europe, 14 May 1864–16 May 1865; James Douglas, Letters to Martha Douglas, 30 Oct. 1871–27 May 1874; David Cameron papers; Jane Dallas letters; J. S. Helmcken papers; J. S. Helmcken, “Reminiscences” (5v. unpublished typescript, 1892); Archibald Macdonald, Correspondence outward, c.1830–1849; John McLeod, Correspondence inward, 1826–37; Donald Ross papers. PRO, CO 60, CO 305. University of Nottingham Library, Newcastle mss, Letter books, 1859–64 (microfilm in PAC).

G.B., Parl., Command paper, 1859, XVII, [2476], pp.15–108, Papers relative to the affairs of British Columbia, May to November 1858; Parl., Command paper, 1859 (Session ii), XXII, [2578], pp.297–408, Further papers relative to the affairs of British Columbia, October 1858 to May 1859; Parl., Command paper, 1860, XLIV, [2724], pp.279–396, Further papers relative to the affairs of British Columbia, April 1859 to April 1860; Parl., Command paper, 1862, XXXVI, [2952], pp.469–562, Further papers relative to the affairs of British Columbia, February 1860 to November 1861; Parl., House of Commons paper, 1849, XXXV, 103, pp.629–50, Papers relating to Vancouver Island and the grant of it to the HBC. . . ; Parl., House of Commons paper, 1857 (Session ii), XV, 224, 260 (whole volume), Report from the select committee on the Hudson’s Bay Company; together with the proceedings of the committee, minutes of evidence, appendix and index; Parl., House of Commons paper, 1863, XXXVIII, 507, pp.487–540, Miscellaneous papers relating to Vancouver Island, 1848–1863. . . . British Columbian (New Westminster, B.C.), 1861–77. Colonist (Victoria), 1858–77. Victoria Gazette, 1859–60. HBRS, IV (Rich); VI (Rich); VII (Rich); XXII (Rich). James Douglas in California, 1841: being the journal of a voyage from the Columbia to California, ed. Dorothy Blakey Smith (Vancouver, B.C., 1965). H. H. Bancroft, History of British Columbia, 1792–1887 (San Francisco, 1890). Coats and Gosnell, Douglas. F. W. Howay, The work of the Royal Engineers in British Columbia, 1858 to 1863 . . . (Victoria, 1910). F. W. Howay and E. O. S. Scholefield, British Columbia from the earliest times to the present (4v., Vancouver, B.C., 1914). J. S. Galbraith, The Hudson’s Bay Company as an imperial factor, 1821–1869 (Toronto, 1957). Morton, History of the Canadian west. Ormsby, British Columbia. W. N. Sage, Sir James Douglas and British Columbia (Toronto, 1930). W. E. Ireland, “James Douglas and the Russian American Company, 1840,” BCHQ, V (1941), 53–66. “Journal of Arthur Thomas Bushby” (Blakey Smith). W. K. Lamb, “The founding of Fort Victoria,” BCHQ, VII (1943), 71–92; “The governorship of Richard Blanshard,” BCHQ, XIV (1950), 1–41; “Sir James Douglas goes abroad,” BCHQ, III (1939), 283–92; “Some notes on the Douglas family,” BCHQ, XVII (1953), 41–51. W. N. Sage, “The gold colony of British Columbia,” CHR, II (1921), 340–59; “Sir James Douglas, K.C.B.: the father of British Columbia,” BCHQ, XI (1947), 211–27.

Cite This Article

Margaret A. Ormsby, “DOUGLAS, Sir JAMES,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 11, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/douglas_james_10E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/douglas_james_10E.html |

| Author of Article: | Margaret A. Ormsby |

| Title of Article: | DOUGLAS, Sir JAMES |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1972 |

| Year of revision: | 1972 |

| Access Date: | March 11, 2026 |