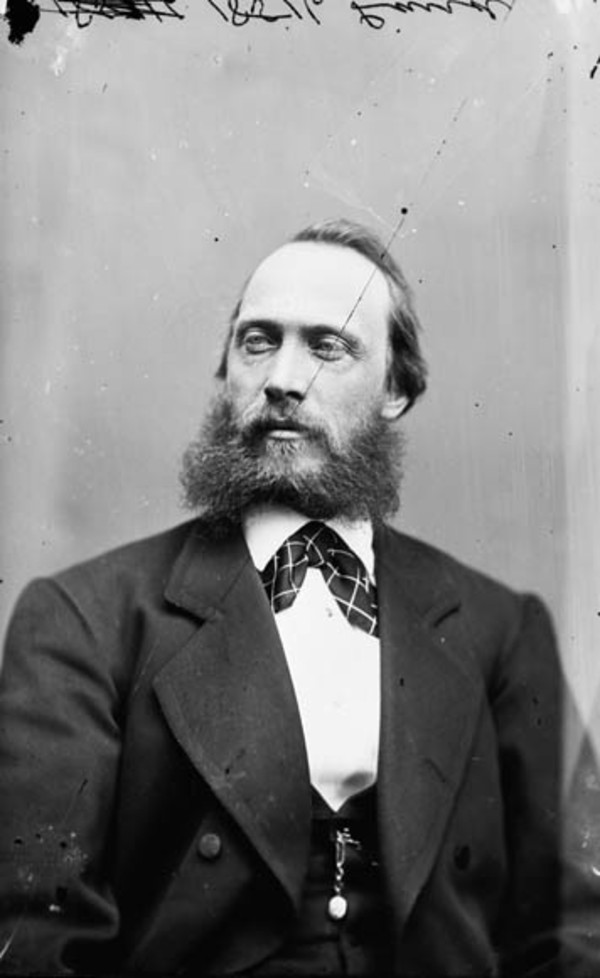

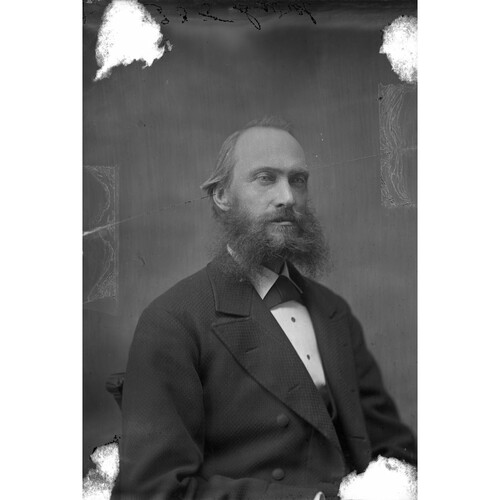

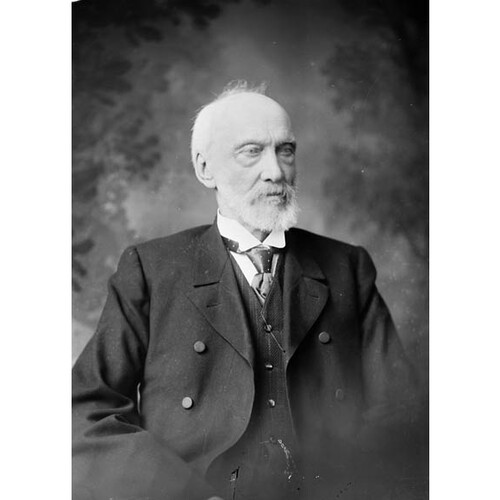

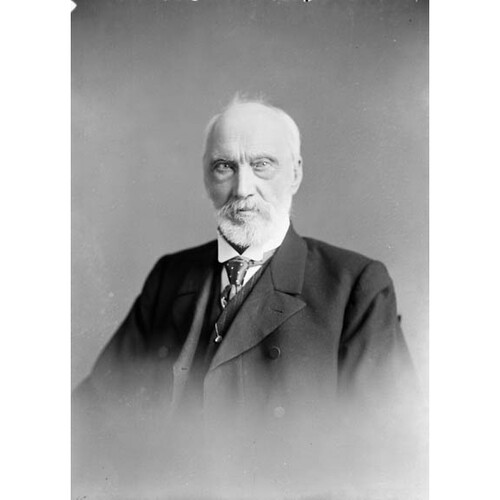

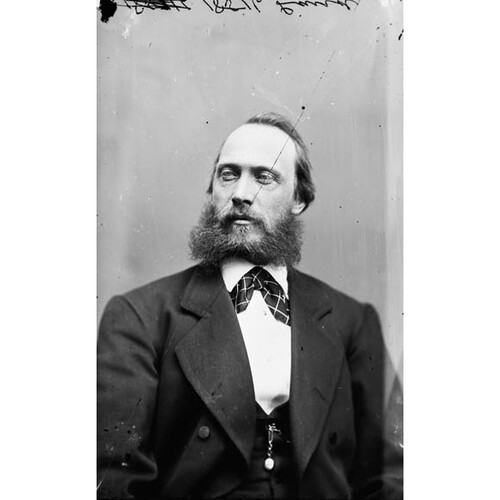

LAIRD, DAVID, newspaper editor and publisher, politician, and office holder; b. 12 March 1833 in New Glasgow, P.E.I.; d. 12 Jan. 1914 in Ottawa.

Much about David Laird was determined by the circumstances of his birth. The son of Alexander Laird*, a prominent farmer and shipbuilder, and Janet Orr, daughter of one of the original proprietors in Prince Edward Island, he carried on the family pattern of political activity, respectable social position, and unbending devotion to the Presbyterian Church. Wherever his career took him, he displayed the habits and fundamental values of his Island upbringing. Sober, pious, high-minded, energetic, and capable, he acted always with the conviction that he was on the side of right and progress.

Laird’s early education was on the Island, first at the local one-room school, and later at Central Academy in Charlottetown. He then attended the Presbyterian Theological Seminary in Truro, N.S., planning to enter the ministry, but as it turned out another calling intervened. After graduation, Laird returned to Charlottetown in 1859 to found, edit, and publish the Protestant and Evangelical Witness. Renamed the Patriot in 1865, with Donald Currie* as associate editor, the newspaper was to become the leading liberal journal on the Island. The politics of religion and education dominated the day in the late 1850s and early 1860s [see George Coles*], and Laird was quick to establish his Protestant credentials. The first issue of the Protestant in July 1859 accepted the task of “exposing the errors and noting the wiles and workings of popery.” Laird carefully recorded that the paper bore individual Catholics no ill will, but only “the system by which they are enslaved.”

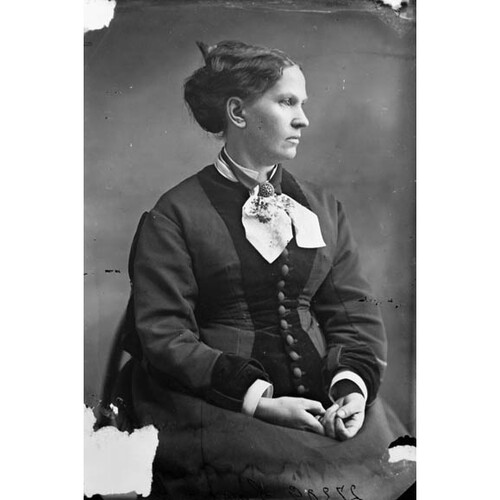

Young Laird soon involved himself in the affairs of Charlottetown. Over the next half-dozen years he found himself a trustee and elder in the church, a member of the Auxiliary Bible Society, a vice-president of the Young Men’s Christian Association and Literary Institute, a member of the Board of Education, and a governor of Prince of Wales College. His first foray into elected office was as a city councillor. On 29 June 1864 he took a major step in becoming an established member of Charlottetown society when he married Mary Louisa Owen, sister of Lemuel Cambridge Owen, the Island’s postmaster general. The marriage would produce six children, four boys and two girls.

Politics was a part of the Laird family tradition. By 1867 David’s father had completed a long career in the legislature and his elder brother Alexander* was just beginning his. His own first electoral ventures, in 1867 and 1870, both ended in defeat, but in a third attempt in July 1871 he was returned to the House of Assembly for Queens County, 4th District, joining the liberal opposition forces led by Robert Poore Haythorne*. Island politics in this period was dominated by three issues: confederation, grants to denominational schools [see Peter McIntyre*], and the Island railway, begun in 1871. Initially, Laird steadfastly opposed all three schemes. The circumstances of the next few years would, however, lead him to reconsider his position. The first change came in 1872, with the defeat of the tory government of James Colledge Pope*. Laird found himself a member of Haythorne’s cabinet, an administration now saddled with the task of completing the railway, which had been the political ruin of the conservatives and was quickly becoming, as Laird had foreseen, the financial ruin of the colony. Demands that branch lines touch the constituencies of virtually every mha proved just as irresistible for Haythorne’s government as for Pope’s. The consequences, especially in the light of Canadian and imperial attempts to add the colony to the new dominion, were profound. By February 1873 Laird and Haythorne were on their way to Ottawa to solicit “better terms” for a union with Canada. They succeeded, and returned to the Island to seek ratification of their achievement in a general election. During the campaign the conservatives promised to negotiate even better terms, and hinted at support for Catholic separate schools. It was enough to sway the electorate, and Laird once more sat in opposition. In short order Premier Pope managed to extract what could be argued were slightly improved terms from the Conservative government of Sir John A. Macdonald*, and the “reluctant maiden” joined the confederation on 1 July 1873.

For Laird, confederation had far-reaching political consequences. The Island was entitled to six seats in the House of Commons, and he soon found himself in Ottawa as an mp for Queens. Four of the six new members were Liberals, and their return had far more to do with the school question on the Island than with dominion politics. All six were expected to support Macdonald, but the unfolding of the Pacific Scandal produced a different agenda. When Laird rose to make his first speech on 4 Nov. 1873, the crisis had reached a peak. The Island members were in a position to destroy, or grant a reprieve to, the beleaguered administration. Laird took the high ground and denounced the government for its apparent lack of “integrity.” Three of the six Islanders, Daniel Davies, James Yeo, and Peter Sinclair*, indicated their intention to follow Laird, as did Conservative Donald Alexander Smith. The government resigned on the 5th. Within two days the Liberals under Alexander Mackenzie* had formed an administration, and Laird had joined the cabinet as minister of the interior and superintendent general of Indian affairs.

Laird’s critics were quick to suggest that he had been bought, but there is no evidence to support their claim. It was Laird’s unbending sense of morality in public life that explained his decision, not a desire for personal advancement. Whatever the cause, one consequence of his decision was the birth of federal political parties on the Island. When Mackenzie dissolved parliament in January 1874 to seek a mandate from the electorate, the result was a victory for the Liberals in all six provincial ridings. Laird was returned with an increased majority, and Islanders prepared to enjoy the fruits of representation in the federal cabinet. Many were to be disappointed.

The Mackenzie government had the misfortune to inherit two of the yet-to-be-fulfilled terms of union with the Island: the provision of winter ferry communications with the mainland and federal operation of the railway. Neither seemed destined for early resolution. Problems in finding a ferry capable of operating in the winter, and the demand of Island communities for their “share” of the inefficient and expensive railway, created constant difficulties for Mackenzie and Laird. Patronage, or the lack of it, also bedevilled Laird’s relationship with Island Liberals. When he failed to deliver the dismissal of Conservative appointees, his stock with the local party began to decline. The most troublesome of his Island-based difficulties was the seemingly perpetual question of religion and education. When, in 1875, the North-West Territories Act was passed, it provided, among other things, for separate schools. Laird, as minister of the interior, had had little to do with the drafting of the legislation, most of the work being done by Mackenzie and the deputy minister of justice, Hewitt Bernard*. No dissent was heard from Island members at the time, and Laird did not participate in the commons debate. In early 1876, however, the Evangelical Alliance of Prince Edward Island launched an attack on the act, describing it as a forerunner of separate schools in the Island province. Laird’s protests to the contrary were less than effective. That the 1876 provincial election campaign was fought largely on the question of religion and education did nothing to dampen the controversy. Laird and his newspaper, traditional defenders of Protestantism and non-sectarian education, were caught in an impossibly awkward position, which Island Tories cheerfully exploited. Within two years, the position of the federal Liberals in Island politics had been eroded badly.

Laird’s designation as minister of the interior had been in some ways an odd choice. He had no firsthand knowledge of the northwest, little enthusiasm for the task of incorporating it into the dominion, no familiarity with its peoples, and a deep scepticism about the promise to complete the Pacific railway and fulfil the terms of union with British Columbia. Other than his reputation for hard work and moral integrity, he brought little to the position.

The northwest for which Laird became responsible in 1874 presented enormous difficulties for a Canada poised to extend its empire. Beyond Red River, Man., the native peoples still were masters of their land, and Laird’s first task was to seek a treaty with the groups through whose territory the railway was to pass. Three treaties had already been negotiated with the Cree and Ojibwa, and these were to provide the framework for the next four, which would bring the entire area of the southern plains under Canadian control. In September 1874 Laird, Lieutenant Governor Alexander Morris*, and William Joseph Christie*, together with a military contingent and interpreters, arrived at Fort Qu’Appelle (Sask.) to negotiate for the huge tract of land between the Qu’Appelle valley and the Cypress Hills (Sask./Alta). The situation was full of potential dangers, and the North-West Mounted Police as yet provided only the lightest presence on the plains. Morris, by far the most knowledgeable and experienced of the three Canadians, took the lead in dealing with the distrust of militant elements among the Indians and was able to reach an agreement based, for the most part, on the terms of Treaty No.3. For Laird as minister, it was both a considerable achievement and an introduction to the west. In return for land grants, cash payments, the promise of tools, seed, and cattle, and other minor inducements [see Paskwāw*], the natives ceded 75,000 square miles of potentially rich agricultural land.

Apart from the negotiation of Treaty No.4, and Treaty No.5 in 1875 [see Jacob Berens], Laird’s tenure as minister was relatively undistinguished. He had little interest in territorial government, and did not even participate in the 1875 debate on the North-West Territories Bill or the 1876 debate on the bill to create the District of Keewatin. One accomplishment was the Indian Act of 1876, which consolidated and amended earlier legislation. Based on the assumption that the government’s goal was the assimilation of the native people, it provided a paternalistic framework for the management of native affairs that has persisted, much amended, into the late 20th century. Otherwise the work of Laird’s department was largely routine, though ably carried out by such seasoned officials as deputy minister Edmund Allen Meredith* and surveyor general John Stoughton Dennis*.

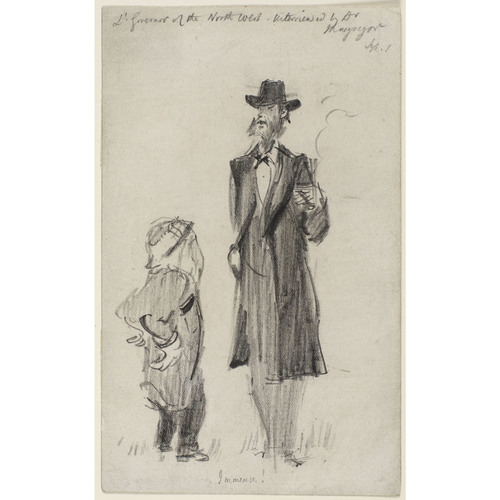

Laird’s experience as minister, his increasingly troubled political relations with the Island, the need for an increased Canadian administrative presence in the northwest, and, perhaps most important, Mackenzie’s wish to accommodate a well-qualified political ally, all contributed to the next step in Laird’s career. In October 1876 he was appointed lieutenant governor of the North-West Territories, and was succeeded as minister by David Mills*. It was an assignment Laird accepted with serious reservations. As he later put it in a letter to Mackenzie, “The truth is I did not want to leave the Government at that time. . . . But you urged me to accept, and, like a loyal supporter, I yielded, supposing that you, somehow, thought it would be in the interest of the country.” The historian Lewis Herbert Thomas suggests that Laird’s appointment “was probably determined by qualities of personality and character which appealed to the Prime Minister – stern morality, caution, and devotion to duty.”

Laird’s role as lieutenant governor between 1876 and 1881 was to earn him, in Thomas’s words, an “honourable if not a distinguished position” in the history of the northwest. Despite being handicapped by distance, severe climate, poor communications, chilly relations with Mills, inadequate staff, and a perennial lack of funds, he proved to be conscientious and well regarded. Without question, the highlight of his term in office was his negotiation, with James Farquharson Macleod*, of Treaty No.7 with the Blackfoot and other tribes of southern Alberta in 1877 [see Isapo-muxika*]. The signing of the treaty in late September removed the last territorial difficulty for the Pacific railway, calmed the tense situation caused by the arrival in Canadian territory of Sitting Bull [Ta-tanka I-yotank*] and his followers, and offered the Blackfoot some small measure of subsistence as the last of the buffalo disappeared along with their traditional way of life.

From his capital at Fort Livingstone (Livingstone, Sask.), and after 1877 at Battleford, Laird presided over a diminutive government. Policy and major decisions were the prerogative of Ottawa, and the Council of the North-West Territories had limited power and influence. Laird’s financial resources were minimal, especially when compared with the area to be administered. Fines and licences provided the only source of local revenue, and during his term these averaged $233 per year. Laird’s fiscal caution was also a factor. One initiative of which he was especially proud and which left an important legacy was the use of federal funds to support schools and public works. In each school at which at least 15 students were present, the government agreed to pay one-half of the teacher’s salary. Although the public works carried out were modest, in part because of the difficulty of supervising projects when the entire bureaucracy consisted of Laird and his secretary and clerk of the council, Amédée-Emmanuel Forget*, they had local significance.

Also burdened with the role of superintendent of Indian affairs, Laird was often hard-pressed to fulfil his responsibilities. During the winter of 1877–78, for example, when many natives faced starvation, he was severely limited by inadequate supplies. He was forced on most occasions to provide for visiting native groups from his personal larder, which on his modest stipend he found difficult. So unhappy was he with his dual role that he wrote to Mackenzie in April 1878 resigning as superintendent. Rebuffed, he reluctantly continued in this office until 1879, when the new Conservative government relieved him. After the defeat of the Liberals in 1878, Laird had to deal with Macdonald as minister. His final years of his term as lieutenant governor were thus often stressful, and there is no record of any regret as he left office in 1881. His legacy in the northwest, Thomas has astutely concluded, “was in the realm of morale – in the influence which high character in public office can have on the life of a society, and particularly of a frontier society.” He was succeeded by Edgar Dewdney, who in 1879 had taken on the position of Indian commissioner for the territories.

Laird returned to the Island in early 1882 to resume his career as editor of the Patriot. Financial control of the newspaper had passed out of his hands, it seems, and money was never plentiful. In the federal election of 1882 he contested Queens once more but was defeated. Five years later he stood, again unsuccessfully, for Saskatchewan, a newly created riding in the North-West Territories. His federal political career was now over.

Back on the Island, Laird resumed work with the newspaper. Money was a constant worry, but he continued to be a leader in the Presbyterian Church and in 1888 was elected as a water commissioner in Charlottetown. In 1895 his wife of 31 years, Louisa, died, leaving him with two daughters at home. At an age when other men were considering retirement, Laird went searching for a job. The election of the Wilfrid Laurier government in 1896 made prospects brighter for a long-serving Liberal, and in 1898 Laird was appointed Indian commissioner for Manitoba and the northwest, based in Winnipeg. One particularly difficult treaty remained to be completed – No.8, dealing with the widely dispersed Woods Cree [see Mostos], Beaver, Chipewyan, and other peoples of the Athabasca and Peace River country. In the summer of 1899, after travelling hundreds of miles, Laird and his party (which included James Andrew Joseph McKenna, James Hamilton Ross*, and Father Albert Lacombe) negotiated the adherence of most of the bands in this remote area. Other officials carried on this work in 1900, as Laird returned to Winnipeg, to continue what by now had become the routine administration of Indian affairs in the west. Two more treaties were made during his time in Winnipeg, though he had no direct role in the negotiations. Treaties No.9 in 1905 and No.10 in 1906 brought the native peoples in what is now northern Ontario and northern Saskatchewan under the administrative control of the Canadian government.

Transferred to Ottawa in 1909, Laird established himself in rooms near the Parliament Buildings, where his office was located. On 12 Jan. 1914, after a short illness, he died of pneumonia at the age of 80, still employed by the Department of Indian Affairs. His funeral was in Charlottetown at the home of his daughter Mary Alice and son-in-law, John Alexander Mathieson*, the premier of the province. In recognition of Laird’s service, the dominion government had ordered the ice-breaker Earl Grey to carry his body across the frozen Northumberland Strait.

The writer of Laird’s obituary in the Patriot noted his intelligence, modesty, devotion to family and church, and deep sense of duty. The western natives, the eulogist noted, had called Laird “the man whose tongue is not forked.” Whatever the longer view of Canada’s native policy in the west suggests, there can be no question of the sincerity and personal honesty Laird brought to the relationship. That the racism and misguided paternalism which underlay the policy were destructive of native society is also certain. But the fundamental responsibility for this outcome rests with the assumptions of Europeans in the Americas, not with David Laird as a man.

NA, MG 27, I, D10. PARO, Acc. 2645; Acc. 2979; Acc. 3099/1. Globe, 2 Feb. 1909. Examiner (Charlottetown), 13 March 1896. Ottawa Citizen, 17 Jan. 1914. Patriot (Charlottetown), 4 July 1867; 16 Dec. 1898; 29 Dec. 1906; 12–13, 15, 19 Jan. 1914. Protestant and Evangelical Witness (Charlottetown), 5 July 1859. Winnipeg Tribune, 12 Jan. 1914. F. W. P. Bolger, Prince Edward Island and confederation, 1863–1873 (Charlottetown, 1964). Canada’s smallest province: a history of P.E.I., ed. F. W. P. Bolger (Charlottetown, 1973). J. W. Chalmers, Laird of the west (Calgary, 1981). O. P. Dickason, Canada’s First Nations: a history of founding peoples from earliest times (Toronto, 1992). F. L. Driscoll, “Federal politics in Prince Edward Island, 1873–1878”

Cite This Article

Andrew Robb, “LAIRD, DAVID,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 11, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/laird_david_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/laird_david_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Andrew Robb |

| Title of Article: | LAIRD, DAVID |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | March 11, 2026 |