Source: Link

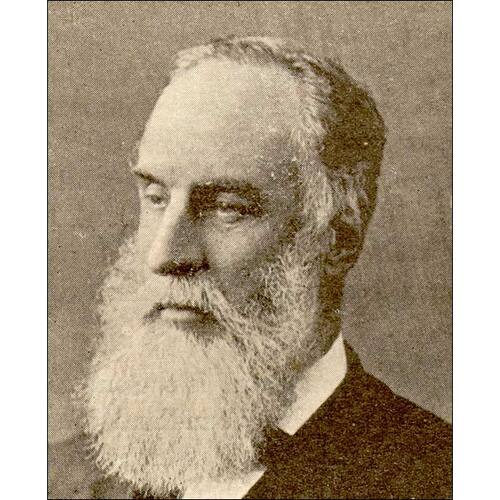

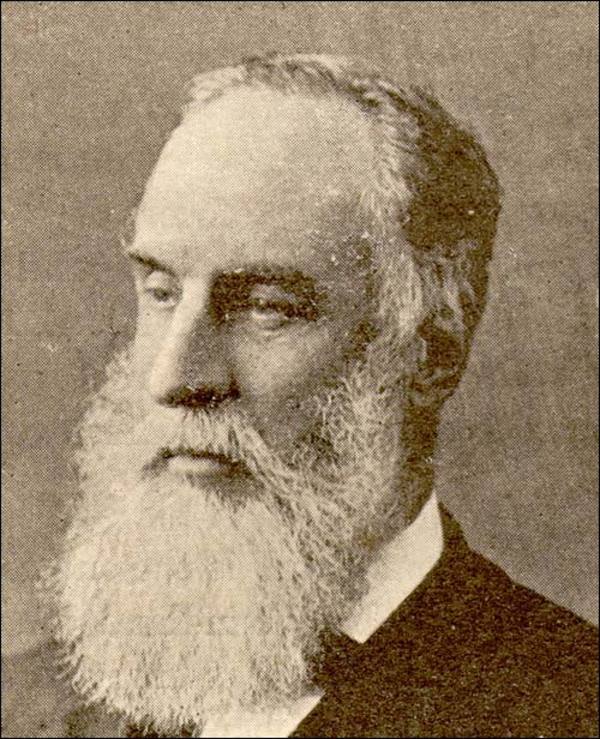

MURRAY, Sir HERBERT HARLEY, governor of Newfoundland; b. 4 Nov. 1829 in Bromley (London), England, son of George Murray, bishop of Rochester, and Lady Sarah Maria Hay-Drummond, daughter of the 10th Earl of Kinnoull; m. 12 July 1859 Charlotte Letitia Caroline Arbuthnot (d. 1884), and they had at least three sons and three daughters; created kcb 1895; d. 11 March 1904 in London.

Educated at Christ Church, Oxford, Herbert Murray entered the civil service in 1852. He was private secretary to the Earl of Derby and then a Treasury official, serving in Ireland between 1870 and 1882. Subsequently he joined the Board of Customs, a body he chaired from 1889 until 1894. His association with Newfoundland began the following year, when he was asked to administer a fund designed to alleviate distress caused by the crash of the colony’s two banks in December 1894 [see James Goodfellow*].

The crash had caused a wave of mercantile bankruptcies and suspensions, and the colonial government itself was in severe financial difficulties. Governor Sir John Terence Nicholls O’Brien painted a bleak picture of the situation, and the British government, while refusing the colony’s application for a loan guarantee and rejecting the idea of a direct grant, opted for a special relief commissioner and fund. Murray was appointed in mid March 1895; he arrived in Newfoundland in early April. Working in conjunction with committees already established by Lady O’Brien and the clergy, he spent some $57,600 on public works, lent $15,421 to inshore fishermen, and provided guarantees of $33,400 to allow schooners to sail to Labrador and the banks. He thought the extent of distress had been much exaggerated and handled his fund with great care. Nevertheless, he enabled many to fit out for the fishery who might not otherwise have been able to, and his administration appears to have met with general approval. As a result, his appointment as governor to succeed O’Brien, who left in July, was welcomed.

Some local politicians had reservations, and with reason, for Murray turned out to be one of Newfoundland’s most difficult and interfering governors. His financial expertise proved useful, but he had no political or colonial experience and clearly accepted O’Brien’s view – by this time also Colonial Office orthodoxy – that Newfoundland was a sink of political iniquity and incompetence. Autocratic by nature, Murray saw himself as a headmaster rather than a governor presiding over a responsible government. With justice, journalist Beckles Willson* wrote that Murray “fatally misunderstands the colony, its needs, and, more emphatically, its politics.” The story of his governorship is one of constant friction between him and his ministers, a contest in which Murray generally received the sympathy of the Colonial Office, then in the hands of Joseph Chamberlain. In 1897 Chamberlain wrote, “The condition of self-government in Newfoundland appears to be a scandal.”

Murray’s disputes with Sir William Vallance Whiteway’s Liberal government, which remained in power until November 1897, focused on three issues: appointments to the Legislative Council, the trials of the former directors of the defunct banks, and reform of the election laws. Murray forced the removal of one member of the council he thought unsuitable and attempted to appoint new members without consulting the government. He hoped thus to convert the chamber into a bastion of respectability that would contain the alleged excesses of the elected branch. One such excess, Murray thought, was Whiteway’s tardiness in bringing the ex-directors to trial. Here he was on firmer ground, for there can be little doubt that Whiteway proceeded with reluctance. The premier’s behaviour, however, did not justify the governor’s abuse, which reached a climax in his comments on the government’s bill, introduced in March 1897, so to amend the Corrupt Practices Act (1889) as to prevent a repetition of the events of 1893–94, when a large number of Liberal members had been unseated for electoral misconduct. Faced with Murray’s dispatches, and hypocritical representations from the Tories, the British government eventually disallowed the legislation, a most unusual step, since it was a matter of local concern.

The disallowance was no doubt one factor in the Liberals’ defeat in the 1897 election. The new administration, led by Sir James Spearman Winter*, may have expected better relations with the governor. If so, it was soon disabused. The occasion was the negotiation in 1898 of a new contract with Robert Gillespie Reid, which in effect sold him the Newfoundland railway and granted him additional lands and franchises. Murray was critical of the contract from the outset. He signed the legislation only when instructed to do so by London, and in the summer of 1898 gave his support to a campaign against the deal led by the new Liberal leader, Robert Bond*. Petitions were circulated calling for disallowance and for Murray’s retention as governor (his retirement had been announced), and he sent them to London with supportive comments, and without first submitting them to the cabinet as custom demanded. He would have welcomed imperial intervention and support for his view that there should be an election on the contract issue. But the Colonial Office was not prepared to act as Murray wanted; indeed, officials were becoming concerned about his partisan activity.

Without waiting for London’s decision, Murray decided to assist the anti-contract forces by moving to weaken the Winter government. He did so by forcing the resignation of Alfred Bishop Morine*, perhaps the most powerful member of the cabinet, on the grounds that he had been Reid’s solicitor, and therefore in conflict of interest, at the time the contract was negotiated, a fact that Murray had known for some time. This action exacerbated the government’s inherent instability, but it managed to hang on to power until early 1900. Murray had left a year before, in January 1899.

Some of the blame for Murray’s behaviour must rest with a Colonial Office that did not do enough to restrain him, but the reason ultimately lies with Murray’s lack of sympathy for the colony and its difficulties. A lonely man – he was a widower – possessing a streak of cynicism and bitterness, he looked about him with suspicion and disdain. His “constant idea,” complained Morine, “was that his lawful advisors were rogues and scoundrels; he rejected their advice and conferred with their enemies . . . . Sir Herbert wanted to run everything according to his ideas . . . and he was not prepared to give credit to the sincerity of anyone who differed from him at any time.” Newfoundland in a period of crisis could have done with a more constructive administrator.

PRO, CO 194/230: 218–22, 368–70; 194/232: 418–19, 439, 451; 194/233: 415; 194/237: 301. Evening Herald (St John’s), 25 Sept. 1895, 27 July 1899. Evening Telegram (St John’s), 1, 6 July, 25 Sept. 1895. Times (London), 12 March 1904. Burke’s genealogical and heraldic history of the peerage, baronetage and knightage, ed. Peter Townend (105th ed., London, 1970). J. K. Hiller, “Hist. of Nfld,” 320–31, 337–43, 348–53; “The railway and local politics in Newfoundland, 1870–1901,” Nfld in 19th and 20th centuries (Hiller and Neary), 123–47. Oxford men & their colleges . . . , comp. Joseph Foster (Oxford, 1893). A. A. Parsons, “Governors I have known,” Nfld Quarterly, 20 (1920–21), no.3: 4. Who’s who (London), 1900: 743. Who was who, 1897–1915 (1988). Beckles Willson, The truth about Newfoundland, the tenth island . . . (London, 1901), 46.

Cite This Article

J. K. Hiller, “MURRAY, Sir HERBERT HARLEY,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 22, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/murray_herbert_harley_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/murray_herbert_harley_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | J. K. Hiller |

| Title of Article: | MURRAY, Sir HERBERT HARLEY |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | February 22, 2026 |