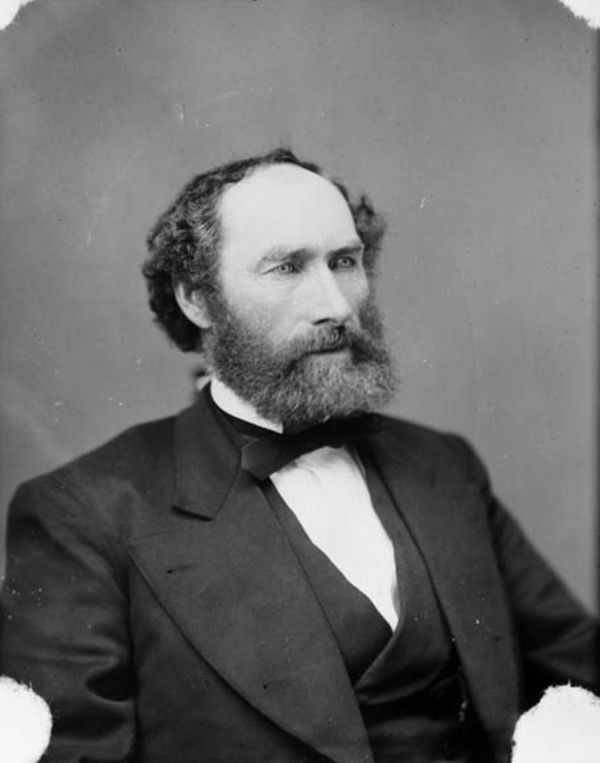

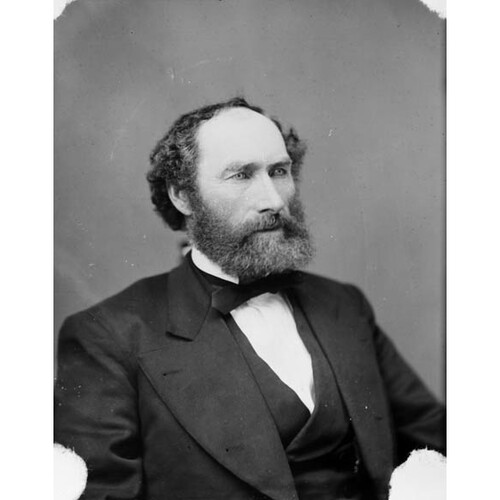

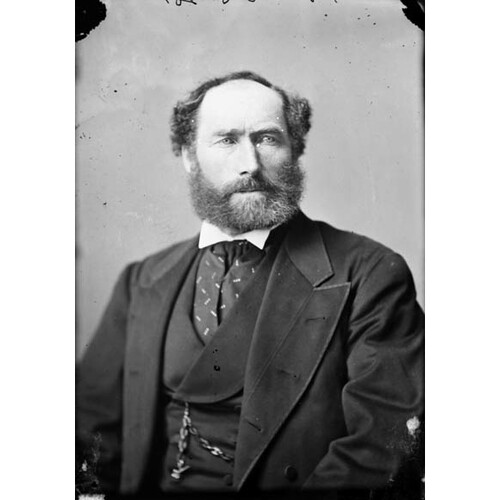

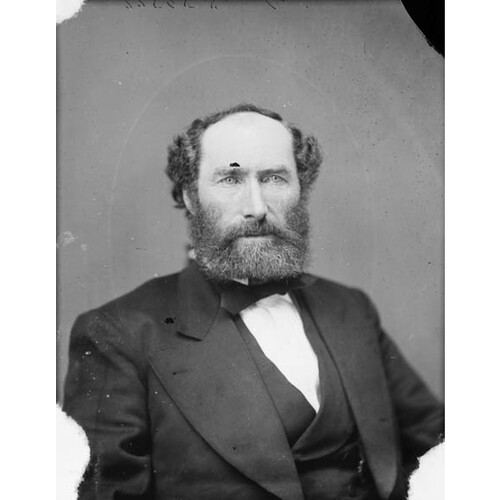

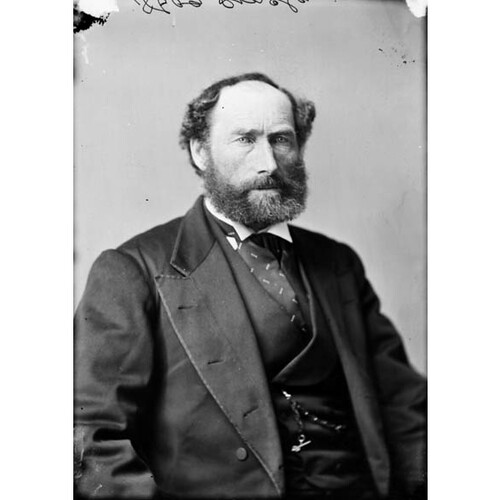

SINCLAIR, PETER, farmer and politician; b. 13 Nov. 1819 in Glendaruel, Cowal peninsula, Argyll, Scotland, son of Peter Sinclair and Mary Crawford; m. 5 Feb. 1879 Margaret MacMurdo in New Annan, P.E.I., and they had four sons and four daughters; d. 9 Oct. 1906 in Summerfield, P.E.I.

The son of a drover who died about 1830 leaving a large family, Peter Sinclair seems to have had a good schooling in Argyll. In 1840 a family group of six emigrated to Prince Edward Island, where Mrs Sinclair purchased a 100-acre farm in a newly settled and inland section of Lot 67, on the western edge of Queens County. Peter settled into building up this farm, named Summerfield after the family home in Scotland.

Active in the community, Sinclair was nominated as the liberal candidate in Queens, 1st District, in 1858. The political tide on the Island was, however, ebbing away from the liberals under George Coles*, and he was defeated. It was not until February 1867, when the liberals were in resurgence on issues related to confederation and the land question, that he was elected for his home district. In his campaign he opposed confederation unless the terms were approved of by the people at the polls. An articulate spokesman for the small farmer, he favoured, on the land question, a measure requiring absentee proprietors to sell.

Well known for his strict views on fiscal responsibility and free schools, Sinclair was placed on the public accounts committee soon after the opening of the House of Assembly in March. The following year he was appointed to the Board of Education and, when Robert Poore Haythorne* took over the administration in 1869, he joined the Executive Council. Sinclair had a strong idealistic side as well: morally he favoured stronger Sabbatarian and temperance legislation. Economically he warned Islanders of the folly of constructing a railway without first investing in better roads, wharves, and navigation. Impressed by the American congressional committee sent to the Island in 1868 to negotiate reciprocity, he became a staunch advocate of free trade. He was an eloquent voice in the Haythorne government’s rejection in 1870 of the “better terms” offered the Island by Canada to enter confederation. He was also vocal in his opposition when Britain, in an effort to push the Island toward confederation, exerted financial pressure to persuade the colony to pay the salary of its lieutenant governor.

By the time of the election of July 1870, the political agenda had shifted to the campaign to provide public funds for denominational schools. Immediately after the election Premier Haythorne made a speech supporting a grant for the Roman Catholic college, St Dunstan’s, but Sinclair and three cabinet colleagues objected. The stalemate that followed resulted in the government’s resignation in September. James Colledge Pope* then formed a coalition administration, which in 1871 pushed through a railway bill. Sinclair opposed it because the question had not been placed before the voters. Further, he argued, the proposal was an attempt to saddle the Island with debt that could only be paid by means of a deal on confederation. As a result of controversy over the Pope ministry’s handling of railway construction, the liberals were returned in 1872. Sinclair was not only chosen government leader in the assembly and a member of the Board of Works, but was also appointed to the cabinet, the only one of the four executive councillors who had opposed Haythorne in 1870 to be included.

Back in power, Haythorne’s liberals were forced to proceed toward rapid completion of the Island railway. Cost overruns developed from the construction of branches and “curves” made in the main line “to suit hon. members,” Sinclair explained to the assembly; indeed, he himself felt that he was asking for nothing “out of the way, to propose a curve for the benefit of his constituents.” By now Sinclair and his government had resigned themselves to confederation.

When the liberals sought confirmation of the terms for confederation negotiated in early 1873, they were defeated in April in an election made more controversial by the denominational schools issue. Sinclair managed to retain his seat. In November he was charged in the Charlottetown Herald, a Catholic newspaper, with being behind a campaign by Protestant ministers to “pledge” candidates in that election. By this time, however, he had resigned to become, in September, one of the Island’s first mps; he and David Laird* were both acclaimed in Queens.

In November, following the resignation of Sir John A. Macdonald*’s federal government over the Pacific Scandal, the Liberals assumed power under Alexander Mackenzie*. Sinclair’s concerns as an Island mp would not always coincide with those of his party. Apart from a speech in the House of Commons in 1875 against federal intervention compelling New Brunswick to establish separate schools, his opposition to denominational schools had little outlet at the dominion level. Although in 1878 he supported his government’s temperance legislation, the Scott Act, he objected to the administration’s attempts to increase the tariff as a means of dealing with the economic depression of the 1870s. His most frequent cause for complaint arose from Canada’s “treaty obligation” to provide continuous communication by steamship between the Island and the mainland. In 1876 he protested that “any Government who think themselves competent to carry through the Pacific Railway need not shrink from crossing the Straits of Northumberland. The interest of this Province is evidently neglected because it is small as compared with the other provinces.” When Laird left Ottawa to become lieutenant governor of the North-West Territories that year, no Island mp was appointed to cabinet to replace him; Mackenzie wrote Sinclair that a province with such a small population “could hardly expect a minister as a matter of local right.” In the dominion election of 1878, five of six Island Liberals were defeated, Sinclair included.

In 1879, at age 59, Sinclair married and began a family. Three years later he re-entered provincial politics, as a member for 1st Queens, one of eleven Liberals elected in opposition to the Tories under William Wilfred Sullivan*. During the 1880s, which were difficult years for the Island, he took a combative position against Ottawa’s neglect of his province, particularly on the issue of winter transportation to the mainland. In 1885 he was so angry over the dominion’s failure to fulfil “the terms of union” that he was “prepared to ask for the abrogation of Confederation.” A formidable critic of the Island’s increasing debt and the unresolved claims on the federal treasury that had accumulated under the Conservatives, he earned himself a place in the cabinet of Frederick Peters in 1891 when the Liberals resumed power. Throughout the final decade of the century Sinclair retained his powerful influence over colleagues and wide public respect. A political opponent, former premier Neil McLeod*, called him “a thrifty farmer and a shrewd business man” in 1891. These qualities were evident in Sinclair’s chairmanship of the Government Stock Farm commission and in his efforts, as chairman of the legislature’s agriculture committee, to improve dairy production and introduce new technology, such as cold storage, to improve markets for Island products. Out of cabinet during the ministry of Alexander Bannerman Warburton* in 1897–98, he was minister without portfolio in Donald Farquharson’s cabinet from 1898 to 1900.

Active and even feisty up to his retirement in June 1900, at age 80, Peter Sinclair had served his province in public life for 33 years. In the latter part of his career, he came to symbolize the grit and longevity of those colonial-era/confederation-period politicians who survived into the 20th century.

PARO, Supreme Court of Prince Edward Island, Estates Div. records, liber 17: ff.171–72 (mfm.). P.E.I. Museum, Geneal. Div., Marriage book no.13 (1873–87): 44. Examiner (Charlottetown), 11 May, 21 June 1858; 28 March 1859; 25 Feb., 4, 16 March 1867; 12 Feb. 1879. Islander, 28 Nov. 1873. Patriot (Charlottetown), 15 March 1873; afterwards Daily Patriot, March–April 1883; March–April 1887; 23 April 1888; 6 April 1889; 26 April 1894; March–April 1896; 22 April, 17 May 1899; June 1900; 20, 23 Oct. 1906. Ross’s Weekly (Charlottetown), 29 Jan. 1863. Royal Gazette (Charlottetown), 1 July 1858. Summerside Progress and Prince County Register (Summerside, P.E.I.), 9, 30 March, 13–27 April 1867. F. W. P. Bolger, Prince Edward Island and confederation, 1863–1873 (Charlottetown, 1964). Can., House of Commons, Debates, 1875–78. Canada’s smallest province: a history of P.E.I., ed. F. W. P. Bolger ([Charlottetown], 1973). CPG, 1874–75, 1889, 1897, 1901. The Gaelic bards, from 1825 to 1875, comp. A. M. Sinclair (Sydney, N.S., 1904), 138. Illustrated historical atlas of the province of Prince Edward Island . . . ([Toronto], 1880; repr. Belleville, Ont., 1972). Frank MacKinnon, The government of Prince Edward Island (Toronto, 1951). Past and present of P.E.I. (MacKinnon and Warburton), 370a, 471–72. P.E.I., House of Assembly, Debates and proc., 1867–73, 1884–86, 1890–93; Legislative Assembly, Journal, 1894–1900. Alan Rayburn, Geographical names of Prince Edward Island (Ottawa, 1973), 117–19. I. R. Robertson, “Religion, politics, and education in P.E.I.” Springfield, 1828–1986 ([Springfield, P.E.I., 1986]). R. D. Tallman, “Annexation in the Maritimes? The Butler mission to Charlottetown,” Dalhousie Rev., 53 (1973–74): 97–112. David Weale and Harry Baglole, The Island and confederation: the end of an era ([Summerside], 1973).

Cite This Article

Kenneth A. MacKinnon, “SINCLAIR, PETER,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 9, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/sinclair_peter_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/sinclair_peter_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Kenneth A. MacKinnon |

| Title of Article: | SINCLAIR, PETER |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | March 9, 2026 |