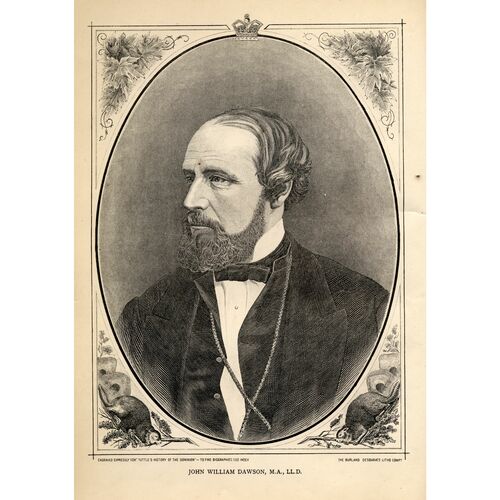

DAWSON, Sir JOHN WILLIAM, geologist, palaeontologist, author, educator, office holder, publisher, and editor; b. 13 Oct. 1820 in Pictou, N.S., son of James Dawson and Mary Rankine; d. 19 Nov. 1899 in Montreal.

John William Dawson (always known as William) was born of Scottish immigrants. At the time of his birth his father was a successful import-export merchant, shipowner, and proprietor of a book and stationery store in Pictou. The severe financial depression of the mid 1820s, coupled with a series of maritime disasters involving his ships, left James in serious financial difficulty. He was able to consolidate his debts with his creditors on the conditions that the money be repaid with interest over the next several decades and that he restrict his business activities to those of bookseller, stationer, and printer. By the 1840s, after more than a decade of genteel poverty, the family had become moderately well-to-do by Pictou standards but the remaining debt was of constant concern, and it was not fully discharged until the 1850s.

A devout Christian, William Dawson felt it his filial obligation to help repay his father’s debts, and this conviction had a great influence on his early adult life. His deep faith had been inherited from his father, an elder of the Presbyterian Church, whose theology was strongly evangelical. A close family friend, the Reverend James Drummond MacGregor*, a staunch anti-burgher, also played a role in forming William’s beliefs. Dawson’s religious convictions were to be an integral part of his life, profoundly influencing his views on science and education.

Dawson received what he called his “academical training” at the Reverend Thomas McCulloch*’s Pictou Academy, the principal function of which was to serve as a preparatory college for Presbyterian ministers. He graduated with a solid foundation in Latin and Greek and a working knowledge of Hebrew, as well as a grounding in physics and biology. On his own he voraciously studied any texts on geology and natural history that came his way. He mounted an impressive collection of minerals, shells, and other natural objects which he collected not only in the countryside around Pictou but as far away as the petrified forest at South Joggins (Joggins), 70 miles to the east. He expanded his collections by exchanging specimens with such Nova Scotian geologists and naturalists as Abraham Gesner*, Thomas Trotter*, and Isaac Logan Chipman, and even traded with naturalists in Boston. In the autumn of 1840 Dawson went to the University of Edinburgh, where he took courses in geology, taxidermy, and the preparation of thin sections of fossil animals and plants for the microscope. During the 1850s and 1860s he achieved an enviable reputation for his microscopic studies of fossils, a reputation that continued throughout his lifetime; he was a Canadian pioneer in this field. His studies were cut short by family financial problems which required him to return to Pictou in the spring of 1841.

Charles Lyell, regarded by most earth scientists today as the father of modern geology, visited Pictou in 1842 to examine the great coal deposits at Albion Mines (Stellarton) south of the town. His principal guide was Dawson, and from this encounter grew a lifelong friendship based on mutual respect. In the mid 1840s Dawson, with the encouragement and guidance of Lyell, did considerable field-work in Nova Scotia, the results of which were published in the Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London. At the same time, on contract, he undertook exploration programs for mining entrepreneurs in search of commercial mineral and coal deposits in Nova Scotia.

During these years Dawson seriously considered becoming a candidate for ordination in the Presbyterian Church. He decided against this step for a number of reasons, but primarily because he could see no way of earning enough money in that calling to help retire his father’s debts, which were still substantial. He was also very much in love with a woman he had met in Edinburgh in 1840, Margaret Ann Young Mercer, the daughter of a prosperous Edinburgh merchant. Although she and Dawson were separated on his return to Nova Scotia in 1841, they conducted a transatlantic courtship by mail until he arrived back in Edinburgh in January 1847. They were married there on 19 March, with the blessing of her father but against the wishes of her mother, who did not attend the wedding and who remained estranged from her daughter for many years.

Dawson had re-enrolled at the University of Edinburgh in the beginning of 1847 to take a course in practical chemistry that would assist him with his commercial explorations. While in Edinburgh he arranged to have lithographed a small geographical map of Nova Scotia, which he had compiled from various sources. This map was included in A hand book of the geography and natural history of the province of Nova Scotia, which he first published in 1848 in Pictou; it later went through many re-editions as a standard textbook for Nova Scotian schools. Printed in a practical pocket-sized format, the Handbook contained a detailed geographical description of the province, county by county, and included short sections on its political and judicial institutions and religious denominations, as well as a statistical analysis of the population. Broad synopses of the geology, fauna, and flora of Nova Scotia were also presented.

When Dawson returned to Nova Scotia in the spring of 1847, it was as the first British North American trained to be an exploration geologist. He did much practical work in the ensuing years, both in Nova Scotia and in various parts of Lower and Upper Canada, on coal, iron, copper, and phosphate deposits. His first major assignment, in August and September 1848, for the government of Nova Scotia, was the evaluation of prospects for the mining of coal in southern Cape Breton Island. At the same time he taught courses in natural history and practical mineralogy at Pictou Academy in 1848 and at Dalhousie College in 1850.

Dawson was keenly interested in the problems of education in his native province, particularly in view of the serious ignorance of agricultural chemistry and other scientific aspects of agriculture among Nova Scotian farmers. He wrote technical papers and newspaper articles on the wheat-midge, a serious local pest, and on the potato blight, which had spread from Europe gravely disrupting local agriculture. In 1850 his friends in the House of Assembly, Joseph Howe* and George Renny Young*, persuaded him to assume the newly created post of superintendent of education for Nova Scotia. Howe’s most persuasive argument was that because the appointment required travel to every corner of the province, Dawson would be able to continue his private geological survey of Nova Scotia as he carried out his official duties.

With the zest for work and accomplishment that was the hallmark of his life, Dawson plunged wholeheartedly into his new career. His first step as superintendent was to visit public schools in Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New York, gathering information on curricula, normal schools, construction of school houses, and school funding. At the outset, he realized the necessity of public support for his proposed reforms, so he systematically visited all the school districts of the province and as many schools as time permitted. In the larger centres he prompted the formation of teachers’ associations and he organized a number of teachers’ institutes, weeklong courses for teachers on various topics with informal discussions on local problems. After two years of travel (1850–51) around the province and investigation into all aspects of education, he recommended the introduction of a standard curriculum taught by trained teachers in local schools. He also recommended a system of taxation to finance these schools and he stressed the importance of a normal school. The Journal of Education for Nova Scotia (Halifax), which he instituted in 1851 and largely wrote, explained and discussed his proposed reforms.

The government was slow to react to his proposals, and Dawson resigned in 1852 when he had completed his report, citing “the requirements of his private interests and duties.” He had been instrumental in organizing the provincial Normal School at Truro, finally opened in 1855, and served as one of its first commissioners. He had vigorously advanced the teaching of agricultural chemistry, and when no suitable text was obtainable he wrote several himself, including Scientific contributions towards the improvement of agriculture in Nova Scotia (Pictou, 1853) and Practical hints to the farmers of Nova-Scotia . . . (Halifax, 1854). A combined and revised version of these texts for use in Quebec schools would appear in 1864, published in Montreal by John Lovell as First lessons in scientific agriculture: for schools and private instruction. . . .

Lyell returned to Nova Scotia in 1852 and set off with Dawson to examine the interiors of the fossil tree trunks exposed in the cliffs of the Joggins shore. The two were rewarded with the discovery of the earliest reptilian remains then known in North America (and rare elsewhere in the world). The reptile was subsequently named Dendrerpeton acadianum. At the same location they found the equally rare remains of a land snail, to be named Pupa vetusta. The discovery of these life forms so far back in geological time was of great significance to palaeontologists and later to evolutionists. Study and description of the Joggins “airbreathers” occupied Dawson, at various intervals, for the rest of his life. In 1863 he published Air-breathers of the coal period . . . (Montreal and New York), his major contribution on the subject and a monograph still highly regarded by palaeontologists. His last major paper on the subject, published in the Transactions of the Royal Society of Canada for 1894, was “Synopsis of the air-breathing animals of the Palaeozoic in Canada, up to 1894.”

In 1854 Dawson was elected a fellow of the Geological Society of London and in that year he completed the manuscript of his monumental work, Acadian geology . . ., which was published in Edinburgh and London the following year. The work was a practical and authoritative guide to the geology and economic resources of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island. The fourth and final edition, revised and updated, appeared in 1891, having grown from an initial 388 pages to almost 700.

It is not surprising, then, that in 1854 Lyell should have strongly advocated Dawson’s candidacy for the chair of natural history at the University of Edinburgh when it fell vacant. A contemporary British geologist, Dr John Jeremiah Bigsby*, reported Lyell as saying at the time, “now I look chiefly to Dawson . . . for any true progress in the Philosophy of Geology.” In August 1855, as Dawson prepared to sail to England to press his candidacy, the news reached him that the chair had already been awarded to botanist George James Allman, primarily because of vigorous lobbying by the medical faculty of the university, which wanted a botanist and not a geologist.

Almost simultaneously, and unexpectedly, came an offer from McGill College in Montreal to become its fifth principal. This offer was made largely as a result of recommendations by the governor-in-chief, Sir Edmund Walker Head*, to the board of governors of McGill. Head had first met Dawson through his old friend Lyell in 1852, during Head’s term as lieutenant governor of New Brunswick. The Pictonian so impressed the lieutenant governor that two years later Dawson had been invited, along with the superintendent of schools for Upper Canada, Egerton Ryerson*, and New Brunswick politicians James Brown*, John Hamilton Gray*, and John Simcoe Saunders*, to join a commission of inquiry into the state of King’s College, Fredericton [see Edwin Jacob*]. The outcome of the commission’s labours was the formation of a non-denominational provincial university, the University of New Brunswick. As governor-in-chief, Head had become ex officio visitor to McGill. It was he who convinced the board of governors that they needed as principal not a distinguished classical scholar from Great Britain but a scientific scholar who was attuned to the educational needs of a young and growing country and who had already established an international reputation. Discouraged by his lack of success at Edinburgh, yet knowing little about Montreal or McGill, Dawson accepted the offer, but he travelled to Britain first and while there delivered several papers at the annual meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science.

What Dawson found when he arrived at McGill with his wife and children in 1855 was daunting. The faculty of arts was moribund; the two college buildings (one of which was to serve in part as the principal’s residence) were in a state of ruin; the college grounds were literally a cow pasture joined to the city of Montreal by a tortuous cart-track which was nearly impassable after dark. Funds for the college were almost non-existent. Apart from a vigorous faculty of medicine [see Andrew Fernando Holmes*], the only encouraging aspect was the composition of the board of governors. It included Charles Dewey Day*, James Ferrier*, and William Molson*, who were to give freely of their time and money to help McGill advance. These men agreed with Dawson that higher education in a colonial society should be guided by practicality. The Canadas at that time needed men with professional skills. Dawson and the board of governors set out to provide them.

The governors found that they had engaged a principal well suited to the tasks ahead. Dawson was both theoretical and practical in his range of interests and expertise. The University of Edinburgh awarded him an ma in 1856, partly because of his publications. He was an experienced educator, with a practical background in business and finance, a brilliant lecturer, a popular author, and a devout Christian. Although endowed with great vigour and determination, he had generally a quiet, kindly, and courteous manner, with a gentle, though at times ponderous, sense of humour. As the years passed, Dawson became a patriarchal figure on the McGill campus, beloved and revered for his thoughtfulness and patience by generations of students, of whom the most vocal in his praises was Sir William Osler*. Each session he would invite small groups of students home to tea until every student had been included. Singsongs were a common occurrence at these gatherings.

At McGill, Dawson’s initial success was the establishment of a normal school in 1857 under a government grant. He was to serve as principal and instructor in science of the McGill Normal School for some 13 years, at great personal sacrifice (as he was to complain later) for the school’s year did not end in early May as did the college’s but continued until late June and thus cut down the time available for the field-work he so dearly loved. In addition to his dual principalships, Dawson was initially professor of chemistry, agriculture, and natural history (which included geology, zoology, and botany) so his teaching schedule was a full one. He did, however, find time to lay out the grounds of the college park, now known as McGill’s lower campus, and with his wife helped plant the great elms that graced it until they were destroyed by disease almost a century later. In little more than a decade after Dawson’s arrival in Montreal, McGill College had become a thriving, steadily growing institution, which was beginning to make a name for itself in eastern North America. Dawson’s innovative and creative research in geology, the most popular science of the mid 19th century, together with his efforts to build a strong faculty in the biological and physical sciences as well as in engineering, laid the foundations for McGill’s reputation. As Stephen Butler Leacock*, the renowned humorist and professor of economics at McGill, was to write later, “More than that of any one man or group of men, McGill is his work.”

Dawson’s removal to Montreal in 1855 brought him into closer contact with American scientists and such organizations as the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., and the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University. He developed lifelong friendships with noted American scientists James Hall, John Strong Newberry, James Dwight Dana, Samuel Hubbard Scudder, and a host of others. Principal Dawson, as he was usually referred to in scientific circles, also maintained strong ties with British institutions and with such eminent British geologists as Lyell, Bigsby, William Crawford Williamson, and Philip Herbert Carpenter. In 1888 he urged the formation of an imperial geological association, but nothing came of his suggestion.

In 1857 the American Association for the Advancement of Science held its annual meeting in Montreal, the first gathering outside the United States. Members were received by Dawson, who was also the newly elected president of the Natural History Society of Montreal. He was to hold this second office for 19 more terms in the ensuing decades, and he contributed enormously to its publication, the Canadian Naturalist and Geologist. . . . He also joined enthusiastically with members of the Geological Survey of Canada (then based in Montreal), such as Sir William Edmond Logan*, Thomas Sterry Hunt, and Elkanah Billings*, in establishing Montreal as a centre of research in geology with an international reputation.

Once he was settled at McGill, Dawson’s opportunities for extended field-work were severely restricted not only by his duties but also by the perceived need to take his family away from the heat of the city during the summer. For most of the 1860s the health of the Dawsons’ eldest surviving son, George Mercer*, was a constant concern. (Their first-born, James Cosmo, had died in infancy in 1849.) In the spring of 1860 George had fallen into a stream (the “burn” of James McGill*’s Burnside estate). He subsequently developed a chill and a spinal infection that severely stunted his growth and left him a hunchback. Dawson closely supervised the education of his son, who as an adult would become one of Canada’s greatest geological explorers. With the health of his family in mind, Dawson chose to concentrate his summer field-work on the study of fossil plants exposed primarily in the Gaspé Peninsula and in Maine. These locations were readily accessible and amenable to brief collecting expeditions. The two localities yielded the earliest known plants in the geological column, and Dawson’s work on them remains one of his most outstanding scientific accomplishments. His paper “On fossil plants from the Devonian rocks of Canada,” published in the Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London in 1859, is considered a landmark in the history of palaeobotany. Of equal importance was his work on fossil plants of the Devonian and Upper Silurian formations of Canada published by the Geological Survey of Canada in 1871.

Upon his arrival at McGill he had begun a close study of the glacial deposits and fossils in the vicinity of Montreal. He later made similar studies in the lower St Lawrence River valley, where he helped to establish the summer colony of Métis-Beach and its Presbyterian church. His contributions to the knowledge of the fossil flora and fauna of the great Ice Age were duly recognized in his lifetime. He continued, however, to adhere to the theory that the principal agent of glacial action was drift-ice, detached pieces of ice which transported boulders and striated bedrock during periods when parts of the earth’s surface were covered with water. His advocacy of this view, as well as his refusal to accept Jean Louis Rodolphe Agassiz’s theory of a great polar ice cap, first put forward in Scotland in 1840, brought him into serious conflict with other geologists. He also had continuing disagreements with the theories of Dana and Newberry. Dawson, however, had grown up on the shores of Nova Scotia, one of only two inhabited places in the world where the effects of drift-ice may be seen every year. In his studies of the glacial materials of Quebec, he found much evidence of deposition by drift-ice. What was not known then was that on the retreat of the great Laurentian ice-sheet, which by its sheer weight had depressed the regions over which it had lain, a body of water now referred to as the Champlain Sea occupied the entire valley of the St Lawrence River and extended into Lake Champlain. Upon this sea many boulder-laden icebergs had floated, leaving their mark on the deposits below. Dawson’s principal work on this subject was consolidated into a monograph, Notes on the post-Pliocene geology of Canada . . . (Montreal, [1872]), which was in turn modified and expanded to appear in 1893 as The Canadian Ice Age . . . (Montreal). In this later work he admitted the existence of large local glaciers in the Laurentians and the Appalachians, but he still did not fully accept the land-ice theory. It was not until after Dawson’s death that the question of how glaciation occurred was resolved, and the theory of land-ice reigned supreme.

In 1864 Dawson was asked by Logan, director of the Geological Survey of Canada, to examine under a microscope some apparently organic remains from the Laurentian series of the Canadian Shield, then the oldest known rocks in the world and considered azoic (without life). Dawson pronounced the remains organic and identified them as belonging to the order Foraminifera, a primitive form of animal life. His identification was confirmed by Carpenter, at that time considered Britain’s leading authority on Foraminifera, and also by a number of eminent palaeontologists. The fossil, named by Dawson Eozoön canadense (dawn animal of Canada), was presented formally in papers published in the Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London for February 1865 by Dawson, Logan, Carpenter, and Hunt. The carefully documented discovery was acclaimed throughout the scientific world as epoch-making. Dawson’s Eozoic Age would come to rank with others such as the Palaeozoic. The following year two geologists from Ireland, William King and Thomas H. Rowney, had the temerity to pronounce Eozoön inorganic, the result of changes wrought by heat and chemicals upon limestone. A great scientific battle over Eozoön canadense was joined in earnest. The controversy was to rage almost to the end of Dawson’s life (in 1895 he was still defending his beloved Eozoön from renewed attack), and he never altered his conviction that the remains were organic. The matter was finally resolved to the satisfaction of most earth scientists when Eozoön-like forms were found amongst the ejecta of Mount Vesuvius, Italy, in 1895, and Eozoön is now considered inorganic.

In 1860 Dawson had written a critical scientific review in the Canadian Naturalist and Geologist of Charles Darwin’s newly published On the origin of species. . . . He pointed out the failures of Darwin’s arguments in so far as the fossil record was concerned, failures still being vigorously debated more than a century later. In this regard, it is ironic to note that when Dawson was being considered for election to the Royal Society of London in 1862, Darwin was one of the co-signers of the testimonial that led to his becoming a fellow. Dawson, of course, had other grounds for attacking Darwin’s theories of evolution. As a devout Christian he firmly believed in God as creator – nature could not be mindless, random, and without plan. He further believed that there was no need for religion to fear science, since Scripture properly interpreted was in harmony with science, as he put forth in Archaia . . . (Montreal and London, 1860) and The origin of the world, according to revelation and science (Montreal, 1877). Carl Clinton Berger puts Dawson’s views succinctly when he points out that Dawson opposed Darwinism not only because of its godless view of nature but also because of its godless view of man. In Darwinism he saw the destruction of religious beliefs and social morality. In 1890 Dawson synthesized his stand in Modern ideas of evolution . . . (London). With prescient insight, he warned that a godless view of nature would lead to the degradation of nature by man. “When we consider man as an improver and innovator in the world, there is much that suggests a contrariety between him and nature, and that instead of being the pupil of his environment he becomes its tyrant. In this aspect man, and especially civilised man, appears as the enemy of wild nature, so that in those districts which he has most fully subdued many animals and plants have been exterminated, and nearly the whole surface has come under his processes of culture, and has lost the characteristics which belonged to it in its primitive state. . . . By certain kinds of so-called culture man tends to exhaust and impoverish the soil, so that it ceases to minister to his comfortable support and becomes a desert. . . . The westward march of exhaustion warns us that the time may come when even in comparatively new countries like America the land will cease to be able to sustain its inhabitants.” In later years Dawson became an active corresponding member of the Victoria Institute of London, England, a society devoted to harmonizing the Bible and science.

From 1855 until shortly before his death Dawson gave countless well-attended public lectures each year on science and the Bible and on related topics to institutions such as the Young Men’s Christian Association (not only in Montreal but throughout Ontario) and the mechanics’ institute; during Christmas vacations he lectured in numerous American cities, including New York, Boston, Philadelphia, and Baltimore. Out of these major lecture series came such popular books as Nature and the Bible . . . (New York, 1875), The geological history of plants (New York, 1888), and Facts and fancies in modern science . . . (Philadelphia, 1882).

In 1872 the popular British weekly magazine Leisure Hour (London), published by the Religious Tract Society, commissioned a series of articles which would be, in Dawson’s own words, “free from the taint of agnosticism.” The articles were republished in book form as The story of the earth and man, published in London in 1873, which went through a dozen authorized editions and two pirated ones issued in the United States. Leisure Hour subsequently published several other series of articles by Dawson. These popular works brought their author widespread renown as a defender of Christianity against godless or agnostic science at a time when most people still lived by the tenet “Man’s chief end is to glorify God and to enjoy Him forever.” In such works Dawson presented natural science and cultural anthropology in a solid but vivid way, always relentlessly attacking Darwinism. The publications did, however, damage his professional reputation amongst younger scientists, damage which has persisted for nearly a century, and which has tended to overshadow his unparalleled achievements as scientist and educator.

It was through his important scientific writings that Dawson gave Montreal an international reputation in the fields of geology and palaeobotany. In that city his zeal, high morality, courtesy, and kindness opened the doors of wealthy families, who readily accepted the fact that he was a “water man” (a teetotaller), and opened their purses to the benefit of McGill. It is doubtful whether an outright advocate of Darwin’s theory of evolution could have obtained this support in the God-fearing provincial atmosphere of Montreal, but Dawson did, because he asserted that science, as the study of God’s works, was a Christian duty, to be supported through a university, as well as a practical necessity for a burgeoning new country.

During his lifetime Dawson published some 350 scientific works, large and small. Of these, some 200 were devoted to palaeontology: more than half of those were devoted to palaeobotany, some 25 per cent to invertebrate palaeontology (exclusive of Eozoön), one-tenth to vertebrate palaeontology (mainly Carboniferous amphibia and reptiles) and the rest to Eozoön canadense. The percentages reveal the balance of interests in Dawson’s scientific life. Of his remaining scientific publications, a major component was his contribution to Canadian glaciology (including Pleistocene palaeontology). Dawson published several textbooks in Montreal for the use of Canadian university students. His Handbook of zoology . . . (1870) had the novel approach of providing examples from the fossils around Montreal, such as corals and other marine animals. In 1880 came Lecture notes on geology and outline of the geology of Canada . . . followed in 1889 by a greatly expanded Handbook of geology for the use of Canadian students.

Montreal workmen excavating foundations for houses near the college in 1860 had come upon bones and other remains of an aboriginal village. Dawson took over the recovering of these objects and identified them as contemporaneous with the visit of Jacques Cartier* to the island of Montreal in 1535. Dawson believed the site to be that of the original Indian village of Hochelaga. He described the find in detail that year in the Canadian Naturalist and Geologist. Although anthropologists have subsequently questioned whether this site is actually Hochelaga, there can be no doubt that Dawson was instrumental in preserving for posterity a unique Canadian anthropological discovery.

In the late 1860s pressure began to be felt in Montreal, as elsewhere, for the higher education of women, and on a visit to the British Isles in 1870 Dawson and his wife investigated efforts being made in England and Scotland. On his return to Montreal later that year Dawson, in consultation with such people as Lucy Stanynought (Simpson) and Anne Molson, advocated the creation of an association modelled on that newly established in Edinburgh. This led to the formation on 10 May 1871 of the Montreal Ladies’ Educational Association which had as its aim lectures on a variety of subjects and eventually the establishment of a college affiliated with McGill. Dawson himself organized and taught its course in natural history. He was convinced of the validity of higher education for women, but he was hampered at McGill by the determined opposition of the faculty of arts, by lack of funds, and by the vexing and controversial question of whether there should be mixed or separate classes. In 1884 Donald Alexander Smith* came forward with a donation of $50,000 to finance the first two years of separate classes for women in the faculty of arts at McGill. Dawson was later to acknowledge that he favoured separate classes to protect the refined and sensitive natures of young women from the rough behaviour of the male students; however, he admitted quite candidly that he would have accepted mixed classes had the benefactor so stipulated.

Discontented with his life in Montreal, Dawson had applied in 1868 for the post of principal at the University of Edinburgh. He felt hampered in his scientific work by the dual load of administrative and teaching responsibilities at McGill, by the lack of time for creative scientific pursuits, and by a feeling of isolation from the mainstreams of scientific thought in Great Britain, Europe, and the United States. His few scientific colleagues in Montreal were either growing old, as was his close friend Logan, or had left for elsewhere, as had Hunt. He received glowing testimonials from home and abroad, but failed to obtain the position. However, release from the principalship of the normal school in 1870 (he was succeeded by William Henry Hicks) and the creation of his much longed-for department of applied science in 1871 kept him at McGill.

Dawson had a profound influence on the development and maintenance of Protestant education in Quebec, both before and after the legislation of 1867 established a separate Protestant educational system in the province. For many years he was a member of the Protestant Board of School Commissioners for the city of Montreal and the Protestant committee of the Council of Public Instruction. He conceived the provincial educational system as being like a pyramid, with McGill at the peak together with the normal school, supported by community colleges such as Morrin College at Quebec [see Joseph Morrin*], and becoming broader and broader in tiers descending to the base of the primary schools. Dawson was always highly supportive of school teachers, and frequently participated in their professional gatherings. Until his death his concerns extended to every level of educational reform in Canada, and he thus helped to adapt education to the needs of a growing country.

While maintaining the absolute necessity of a separate school system in Quebec, Dawson was unsympathetic to the establishment of separate Catholic systems in Nova Scotia or elsewhere in Canada, such as in Manitoba. He contended that there should be one public system to provide an enlightened, progressive, non-sectarian education. Only in Quebec, where the French Roman Catholic majority imbued all elements of its educational system with a strong religious flavour and would not provide the type of education he sought, did Dawson feel that a separate Protestant system was justified.

Dawson was always an active participant in his church’s endeavours. While in Nova Scotia he had worked for the Foreign Missionary Society of the Presbyterian Church and was treasurer of the Synod of the Free Church of Nova Scotia for two years (1849 and 1850). He was also a devoted member of the temperance movement, and remained so throughout his life. During his years in Montreal he was active in the Sabbath school movement and produced over 40 detailed outlines of biblical texts for use in the training of Sabbath school teachers. He strongly opposed the introduction of organ music into church services on the grounds that it would distract from devotions and that the money required to purchase an organ would be better spent on more pressing good works. Because of the controversy arising out of the use of organ music in his own Montreal congregation, he withdrew from Erskine Presbyterian Church in 1874 and was one of the founding members of Stanley Street Presbyterian Church. He also served as president of the Montreal auxiliary of the British and Foreign Bible Society.

Although his commitments in Montreal left him little time for research, in 1871, with the aid of Dr Bernard James Harrington*, professor of chemistry and mineralogy at McGill and later his son-in-law, he surveyed Prince Edward Island and issued for the provincial government Report on the geological structure and mineral resources of Prince Edward Island (Montreal, 1871).

In 1878 Dawson received a tempting invitation from the College of New Jersey, at Princeton (then a centre of the battle against Darwinian theories of evolution), to become professor of natural history. In addition to a salary that more than matched his income from McGill the offer carried with it the more important opportunity to lead palaeontological expeditions to the American west, where important discoveries of fossil animals and plants had recently been made. Dawson declined the offer, however, citing as his reason the obligation to remain in Montreal and continue the battle for Protestant educational rights and institutions in the province. Dawson’s refusal was also greatly influenced by a gift to McGill from his friend Peter Redpath for the construction and endowment of a museum of natural history, contingent upon Dawson’s agreement to remain at the college. The Peter Redpath Museum, a lifelong dream of Dawson’s, was inaugurated in 1882 and still dominates McGill’s lower campus. Prominent in its entrance hall was an illuminated plaque reading: “O Lord, how Manifold are Thy works! All of them in wisdom Thou hast made.”

The Geological Society of London awarded Dawson the Lyell Medal in 1881 for outstanding achievements in geology. In the same year the governor general, the Marquess of Lorne [Campbell*], called upon him to set up a royal society in Canada. Dawson envisaged a society similar to the Royal Society of London, but Lorne was adamant that the Canadian society’s scope be broader and that it embrace not only science but also arts and literature. Lorne realized that only in this way would it be possible to involve to any significant extent the scholars and professionals of the French-speaking community. Accordingly, a provisional council met with Lorne at Dawson’s home in December 1881. Present were Dawson, Hunt, Pierre-Joseph-Olivier Chauveau*, Narcisse-Henri-Édouard Faucher de Saint-Maurice, Daniel Wilson, Goldwin Smith*, Charles Carpmael, Alfred Richard Cecil Selwyn*, George Lawson, and John George Bourinot*. Together they drew up a constitution and proposed candidates for membership. The society was to be organized into two sections for the humanities and two sections for the sciences. Dawson, the founding president, remarked in his address to the first meeting of the Royal Society of Canada in May 1882 that membership was to be limited to “selected and representative men who have themselves done original work of at least Canadian celebrity.” The society was to provide, in his words, “a bond of union between the scattered workers now widely separated in different parts of the Dominion.” Its Transactions, to which Dawson would contribute numerous papers, notably on the fossil plants of western Canada, was for many years one of the principal Canadian outlets for the scholars of Canada.

In 1882 the American Association for the Advancement of Science met once again in Montreal, with Dawson as its president. The formal opening of the Peter Redpath Museum was one of the great attractions of the meeting, which was a landmark in Canadian scientific history. In 1884 the British Association for the Advancement of Science held its annual meeting in Montreal, for the first time ever outside the British Isles. Two years later the association elected Dawson president, a post he considered the greatest honour of his career. He thus became the only individual ever to have held the presidencies of both the British and the American societies, the two leading scientific associations of the time.

Dawson took his first and only sabbatical leave in 1884 and travelled with his wife and their elder daughter, Anna Lois, to Italy, Egypt, and the Holy Land. The results of this “vacation” were a stream of papers on the geology and anthropology of Egypt, Lebanon, and Syria, and a large volume entitled Modern science in Bible lands (New York, 1887), which went through several editions. Dawson had been named cmg on 24 May 1881. On 11 Sept. 1884 he was created knight bachelor and in the same year his alma mater, the University of Edinburgh, awarded him an lld (McGill had conferred the same degree on him in 1857).

After suffering a severe attack of pneumonia in 1892, Dawson was ordered by his physicians to spend the winter months in a warmer climate. He dutifully passed that winter in Florida, but on his return to Montreal in the spring of 1893 his health was still precarious, and he was advised to lead a less strenuous life. With regret, after 38 years as McGill’s principal, he retired in June. An educator of extraordinary energy and vision, he had led the college, which from 1885 was known as McGill University, through years of unprecedented growth, raising it in scope and influence to become one of the world’s great universities – “second only to Harvard in North America” read his obituary in the Times of London in 1899. Following his retirement Dawson remained active, and later in 1893 he presided over the annual meeting of the Geological Society of America as its fifth president, an indication of his high standing within American geological circles. He published Some salient points in the science of the earth in London that same year, and it may be considered his scientific autobiography. In England in 1896 Dawson, aged 75, gave the keynote address to the jubilee conference of the Evangelical Alliance. That August he read an interesting paper on Precambrian fossils before the annual meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science and carried out field examinations in Wales. In this decade he produced several of his lengthier religious tracts, including Eden lost and won (London, 1895) and The seer of Patmos and the twentieth century (New York and London, 1898). He also published in Montreal a third edition of The testimony of the Holy Scriptures respecting wine and strong drink . . . (Montreal, 1898), which had originally been delivered in 1848 as an address to the Pictou Total Abstinence Society.

Sir John William Dawson died peacefully after a protracted bout of illness on 19 Nov. 1899. He was deeply mourned in Montreal and throughout his adopted province, and his passing was prominently noted in many cities in North America and abroad. He was survived by Lady Dawson, three sons, George Mercer, William Bell, and Rankine, and two daughters, Anna Lois and Eva.

The autobiography of Sir John William Dawson was published posthumously as Fifty years of work in Canada, scientific and educational . . . , ed. Rankine Dawson (London and Edinburgh, 1901). Dawson is the author of more than 400 books and articles on numerous subjects. The National union catalog and the British Library general catalogue list his monographs, and the bibliographical works cited below are useful for his articles. The present authors have deposited in McGill Univ. Arch. a bibliography of all Dawson’s writings.

McGill Univ. Arch., MG 1022; RG 2, J. W. Dawson, 1855–93. McGill Univ. Libraries, Dept. of Rare Books and Special Coll.,

Cite This Article

Peter R. Eakins and Jean Sinnamon Eakins, “DAWSON, Sir JOHN WILLIAM,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 13, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/dawson_john_william_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/dawson_john_william_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Peter R. Eakins and Jean Sinnamon Eakins |

| Title of Article: | DAWSON, Sir JOHN WILLIAM |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | February 13, 2026 |

![John William Dawson, M. A., LL. D. [image fixe] / Compagnie de lithographie Burland-Desbarats Original title: John William Dawson, M. A., LL. D. [image fixe] / Compagnie de lithographie Burland-Desbarats](/bioimages/w600.1829.jpg)