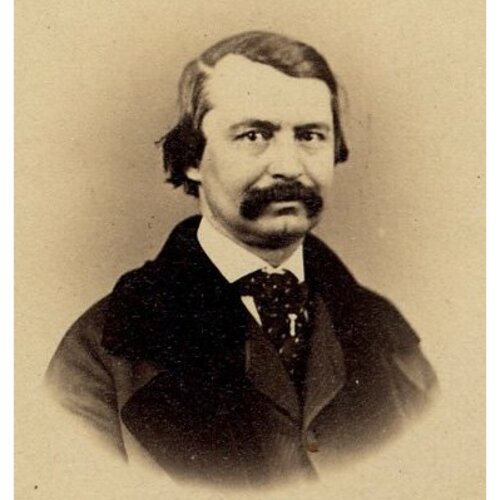

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

DESSAULLES, LOUIS-ANTOINE, seigneur, journalist, author, politician, and office holder; b. and baptized 31 Jan. 1818 in Saint-Hyacinthe, Lower Canada, eldest son of Jean Dessaulles*, a seigneur, and Marie-Rosalie Papineau; m. there 4 Feb. 1850 Catherine-Zéphirine Thompson, his third cousin, and they had a daughter, Caroline-Angélina*; d. 4 Aug. 1895 in Paris and was buried two days later in the Pantin cemetery.

In 1825 Louis-Antoine Dessaulles entered the Collège de Saint-Hyacinthe, which had been founded by his godfather, parish priest Antoine Girouard*. He continued his studies at the Petit Séminaire de Montréal from 1829 to 1832. The final part of the classical program, Philosophy, he did at Saint-Hyacinthe from 1832 to 1834, the very place and time in which the philosophical and political views of Hugues-Félicité-Robert de La Mennais were the focus of heated controversy [see Jacques Odelin*].

In the autumn of 1834, “in the midst of political unrest and constitutional struggles,” Dessaulles began his legal studies in Montreal. He lived there with his uncle, Louis-Joseph Papineau*, who was like a second father to him. Present at the meetings of the Patriote party’s central standing committee for the Montreal area, the young man witnessed the clashes between the Fils de la Liberté and the Doric Club in the autumn of 1837. He assisted Papineau, who, in danger of arrest, disguised himself and left Montreal for Varennes and Saint-Denis on the Richelieu shortly before the outbreak of fighting on 23 Nov. 1837.

At Saint-Hyacinthe, the Patriote leaders included assemblyman Thomas Boutillier*, Philippe-Napoléon Pacaud*, and members of the Papineau family. Mme Dessaulles herself hid the daughter of Wolfred Nelson*, arranged for provisions to reach the camp at Saint-Charles-sur-Richelieu, and sent Louis-Antoine to Saint-Denis to offer the family of Côme-Séraphin Cherrier* shelter in her house. It was on the morning of the battle there that Dessaulles apparently heard Nelson tell Papineau not to take part.

When Papineau fled to the United States after a brief stay in Saint-Hyacinthe, the Dessaulles continued to stand by his family. Louis-Antoine accompanied Mme Papineau (Julie Bruneau) when she left New York in July 1839 to join her husband in exile in Paris. Dessaulles stayed in Europe until November, eagerly observing events in Paris and London, and was commended to everyone by Papineau as “my alter ego.” There he undoubtedly discovered not only a new way of life but also a new focus. La Mennais’s work, Affaires de Rome, published in Paris in 1837, confirmed Dessaulles in a thenceforth unshakeable determination to denounce the political interference and the temporal interests of the Roman Catholic Church.

After various stays in the United States and another trip to Europe (from October 1842 to March 1843), the 25-year-old seigneur was thoroughly awakened to economic realities and became persuaded that he should bring “industry” to Saint-Hyacinthe. But in the early 1840s income from the seigneury never exceeded expenditures and liabilities. Dessaulles borrowed to a worrying extent, sometimes mortgaging the whole seigneury, sometimes using only his seigneurial rights as collateral. In 1845, according to Julie Papineau, he was on the verge of financial ruin and was thinking of selling everything.

In the elections for the Legislative Assembly in the autumn of 1844, Dessaulles ran in Saint-Hyacinthe against Boutillier, the sitting member and a supporter of Louis-Hippolyte La Fontaine*. La Fontaine’s group felt that, to preserve ideological alignments, the Reform majority in Lower Canada should not take part in a government dominated by the tory majority of Upper Canada. On the other hand, members such as Denis-Benjamin Viger* and Papineau’s brother Denis-Benjamin* agreed to sit on the Executive Council for the sake of the double majority, believing that French Canadians must be represented in the administration. Defeated in the election, Dessaulles unsuccessfully contested the results. In December 1847, at the time that Papineau, having returned from exile, was a candidate for Saint-Maurice, Dessaulles began from Saint-Hyacinthe the first of four phases of his important work on the Montreal newspaper L’Avenir. Until the summer of 1848 Dessaulles – alias Anti-Union, Campagnard, or L.A.D. – called for repeal of the 1841 union of the Canadas and defended the intransigent position Papineau was taking against La Fontaine’s policy, which had become one of compromise. He tried to rally support behind Papineau. In the autumn and winter of 1848, during a controversy over Papineau’s conduct at Saint-Denis – “running away,” or a “departure at the invitation of Nelson” – Dessaulles opposed the interpretation “running away.” His articles were reprinted in the pamphlet Papineau et Nelson; blanc et noir . . . et la lumière fut faite (Montréal, 1848). In 1849 L’Avenir published his anticlerical “correspondence” condemning the stance of the church and of its “organs,” which blatantly favoured the compromise policy of the Reformers, now in power.

At the end of November 1849 Dessaulles was elected mayor of the village of Saint-Hyacinthe, which became a town the following year, and he remained in office until April 1857, enjoying the support of councillors Donald George Morisson, his cousin, and Maurice Laframboise*, his brother-in-law. The town had 3,313 inhabitants at the time of the 1851 census and was prospering from the railway boom; the Longueuil to Saint-Hyacinthe line was opened at the end of 1848 and was later extended to Portland, Maine, and Pointe-Lévy (Lauzon and Lévis).

Dessaulles was a member of the annexationist movement. In 1850 and 1851 he set out his position in L’Avenir and in the pamphlet Six lectures sur l’annexion du Canada aux États-Unis (Montréal, 1851). At the outset he asked, “What country are you from?” Observing his contemporaries’ desire for national independence and the progress made toward sovereignty, he took note of the end of British protectionism, which signalled “the hour of separation” and of “the new direction for business.” These lectures were in fact a “detailed critique of the monarchical colonial government” compared to the American institutions that he so greatly admired. It was as a French Canadian that Dessaulles (under the pseudonym Anti-Union) had spoken out against maintaining the union of Upper and Lower Canada. But it was as a liberal, concerned about prosperity and individual liberties, that he came out in favour of the annexation of Lower Canada to the United States.

A seigneur although an admirer of the American republic, Dessaulles had to explain his position on the seigneurial question, which he did in L’Avenir in April 1850. He acknowledged the people’s right to change institutions, though certain grievances concerning seigneurial tenure seemed to him ill founded He reminded his readers that private property is a matter of natural right and that the minority has rights, and he stressed that the system could only be changed with full compensation to owners.

In January 1852 the Montreal paper Le Pays, financed by Édouard-Raymond Fabre* and founded to defend the cause of the “true democrats in Canada,” was launched. Dessaulles joined it for a few months as editor, along with Louis Labrèche-Viger*.

While continuing his duties as mayor and seigneur of Saint-Hyacinthe, and lecturer at the local mechanics’ institute and the Institut Canadien, in the autumn of 1854 Dessaulles again ventured into provincial politics, this time as a candidate in Bagot. He was defeated by a narrow margin, 922 votes to 897. In six of the eight parishes in his riding he had won, but in Saint-Hugues and Sainte-Hélène (Sainte-Hélène-de-Bagot) he had come up against the influence of parish priest Louis-Misaël Archambault. Archambault figures in the “Cahier de notes (1852–1874)” that Dessaulles kept on the clergy. It contains, in alphabetical order by name (with dates, places, and sources), two kinds of information: “facts” about instances of clerical influence being used against liberals, and “facts” about the relations of priests with women. Dessaulles would later say, “One can almost always unhesitatingly deduce from rabid political sermons [against the liberals] the dubious morals of their authors.”

In the autumn of 1856 Dessaulles was elected to the Legislative Council for the division of Rougemont. It was the first time that councillors had been elected rather than appointed; Dessaulles was the only “democrat” to win one of the 12 seats contested in Lower Canada. He had the support of almost all the voters of Saint-Hyacinthe (both town and parish), three-quarters of those in the riding of Rouville, and two-thirds of those in Iberville. His 1858 pamphlet À messieurs les électeurs de la division de Rougemont was critical of the Conservative ministers, who, after the 48-hour government of liberals George Brown* and Antoine-Aimé Dorion, returned to power within a few days of their resignation by the notorious “double shuffle” – simply changing posts in order to avoid having to go through an election. The independent liberal member from Saint-Hyacinthe, Louis-Victor Sicotte*, also came under fire in the pamphlet.

Toward the end of 1859, Dessaulles, along with Dorion, Lewis Thomas Drummond*, and Thomas D’Arcy McGee*, was on the committee that drew up a manifesto of the parliamentary opposition from Lower Canada. On the constitutional question it proposed that the union of Upper and Lower Canada remain, but within a decentralized federation. In a letter to Brown on 14 Oct. 1859, Luther Hamilton Holton* explained, “Some of our more advanced Rouges . . . fear the ascendancy of retrogressive ideas and especially the effects of clerical domination in Lower Canada if separated from Upper Canada.” He gave Dessaulles as his first example – meaning the liberal, anticlerical Dessaulles.

Dessaulles regularly attended the sittings of the Legislative Council, at Toronto and at Quebec, and in seven years he presented no fewer than 177 petitions on behalf of individuals, municipalities, “literary” institutes, and Catholic charities. He was a member of the committee on publications and the library of the legislature, as well as of the committee to inquire into the construction of public buildings in Ottawa.

On 1 March 1861 Dessaulles, who had recently moved to Montreal with his family, took on the editorship of Le Pays, a decision that caused him a number of problems and brought criticism from his political foes. At that time Le Pays was an opposition liberal paper. However, with the formation in May 1862 of the administration headed by John Sandfield Macdonald* and Sicotte, it gradually became more sympathetic to the government and came out openly in its support by the summer of 1863, when Dorion and the ministers appointed by him for Lower Canada replaced Sicotte and his colleagues. Personalities aside, the progressive liberals of Montreal and Le Pays were quite distinct from the moderate liberals and L’Ordre, a Montreal newspaper founded in 1858 which sought to make peace with the clergy for religious and political reasons.

The editor of Le Pays was actively involved with the general elections of 1863 and with the by-elections in Bagot and later in Saint-Hyacinthe, which his brother-in-law Laframboise and his cousin Augustin-Cyrille Papineau respectively contested as candidates. As a result of the electoral struggle in the Saint-Hyacinthe region, where the political and religious debates in public meetings and in the newspapers were particularly acrimonious, Dessaulles was personally taken to task by Cyrille Boucher*, the former editor of L’Ordre, who found fault with his unorthodox 1858 lecture on progress. Louis Taché, a notary from Saint-Hyacinthe, also accused him of having had in his possession, during his term as mayor, a sum of money corresponding to the value of bonds belonging to the municipality. At the end of November 1863, the editor of L’Ordre, Labrèche-Viger, who had been, with Dessaulles, one of the original editors of Le Pays in 1852, condemned the “philosophical dissertations which do little to advance the interests of the liberal party.” One month later the Macdonald–Dorion government appointed Dessaulles clerk of the crown and clerk of the peace, offices which obliged him to resign from the Legislative Council and the editorship of Le Pays. Dessaulles at 45, though he had a considerable record of service, had become an embarrassment to the party during its brief time in power.

In 1859 a public announcement had been made of the appraised value of seigneurial rights and properties which was to serve as the basis for compensation agreed upon in 1854 for the commutation of seigneurial tenure. The assets of the Dessaulles seigneury had been evaluated at about $125,000 (since three-fifths of the value of the communal mill still belonged to the heirs of Pierre-Dominique Debartzch*). But the liabilities were also sizeable. It was rumoured that Dessaulles had had difficulty proving that he actually had in hand the $8,000 in property required to qualify for his seat on the Legislative Council.

The truth was that the erstwhile seigneur had failed as a capitalist. He believed he had found with railway construction the opportunity to recover his fortune through the production of timber and lime, as well as through a transport firm; the latter enterprise connected the hill of the parish of Saint-Dominique with the railway station at Britannia Mills, not far from Saint-Hyacinthe, by a “rail road” using wooden rails with metal reinforcements and horse-drawn carriages. But all of these operations had reached a peak around 1854 and then declined, particularly after 1860. Dessaulles, their promoter, lost thousands of dollars. Circumstances may have been partly to blame. It is quite clear, for example, that the locus of benefits to the economy from railway construction moved progressively farther to the east of Saint-Hyacinthe. The ventures certainly provide no evidence of Dessaulles’s administrative abilities, but it must be pointed out that his energies were dispersed in an unusually wide variety of activities.

On 1 July 1867, the inaugural day of the confederation to which Dessaulles had been fiercely opposed, a legal order of sale by auction was issued to the owner of the Dessaulles seigneury. The auction was held a few days later and no one was willing to bid more than the $32,025 offered by Robert Jones. One significant detail, at least for Dessaulles, was the fact that the sheriff officiating was none other than Louis Taché. The former seigneur of Saint-Hyacinthe was left with nothing but debts; he owed about $15,000 in 1869 and five times that amount in 1875.

Another of Dessaulles’s concerns had been his membership in the Institut Canadien of Montreal. He had become an active member in 1855 but in the spring of 1858, when he was a legislative councillor and still living at Saint-Hyacinthe, he played no prominent role in the decision by the institute’s majority to refuse the demand of a minority, who, at the instigation of ecclesiastical authorities, wished to remove the “evil books” and militant Protestant newspapers from the library and reading-room. From 1850 to 1871 he was attracting public attention with 20 lectures on ten or so different topics, including annexation to the United States (1850 and 1851), the condemnation of Galileo (1856), and progress (1858). When the bishop of Montreal wrote seven private letters to the owners of Le Pays suggesting that the paper modify its position on religious questions, Dessaulles, as editor, responded early in 1862 with “Aux détracteurs de l’Institut canadien, grands et petits.” From then on he personified the institute’s resistance to the clergy in general and to the bishop, Ignace Bourget*, in particular.

Dessaulles was president of the Institut Canadien from May 1862 to May 1863, from May 1865 to May 1866, and from November 1866 to May 1867. In 1863 and 1864 he was the leading member of the committee appointed to “inquire into appropriate ways of smoothing out the difficulties” with Bourget. His was the first signature on the petition to Rome in 1865 from “17 Catholic members of the institute.” Late in 1866 at a large reception inaugurating its new building, he gave a long lecture outlining the history of the conflict with the ecclesiastical authorities. Le Courrier de Saint-Hyacinthe attacked both this defence of the institute and its author. In his response Dessaulles suggested that the influence of the priests of the Séminaire de Saint-Hyacinthe was behind the attack, and the superior Joseph-Sabin Raymond* replied. In the course of the first half of 1867, both of them wrote some 20 letters, which they published respectively in Le Journal de Saint-Hyacinthe and Le Pays and in Le Courrier. From discussion of the specific “political” role of the seminary they moved on to the implications. Dessaulles, whom his adversary described as “the head of the school of thought wishing to change the ideas and practices which have so far prevailed,” contended that it was the conduct of the clergy themselves which had changed in the last 20 years and that what lay ahead was theocracy.

The papal condemnation of 7 July 1869 was more strictly aimed at the Annuaire of the Institut Canadien for 1868, and Dessaulles’s plea for tolerance which was its main feature, than at the institute itself. The year-book was put on the Index, but Bourget interpreted the ban broadly and condemned the institute as well. Before long there was a second private appeal to Rome from four members, including Dessaulles and Gonzalve Doutre*. These events occurred on the eve of the controversy arising from the death of Joseph Guibord*, a member who was refused Catholic burial.

On 29 Dec. 1869 and 11 Jan. 1870 Dessaulles once again lectured at the institute; his topics were Guibord and the Index. He continued his “great ecclesiastical war” until 1875, taking aim at Bourget, the Programme Catholique [see François-Xavier-Anselme Trudel*], and the ultramontane press. His efforts were to no avail. Since there was little popular support for militant resistance to the power of the clergy in society, it was futile for Dessaulles to write that no one had answered the real question – whether a Catholic could belong to an organization owning books on the Index – and it was equally futile for the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London to uphold the cause of those defending Guibord’s right to burial in a Catholic cemetery.

In desperate financial straits from 1870, Dessaulles could no longer keep his creditors at bay at the height of the economic crisis of 1875. Nor could he continue to resort to what he himself would call a “dishonest” and “shameful” stratagem for prolonging his “intolerable situation” by keeping for his personal use the money collected in the course of his duties. He fled to the United States, his reputation ruined. At sea en route to Europe, he wrote a poignant letter to his wife on 1 Aug. 1875, admitting what he had done and concluding with a prosaic detail: the keys are on the desk. The Conservative and Catholic newspapers were politely ironic about his fate when his commission as clerk was rescinded on 13 Sept. 1875.

The “exile” went first to Belgium, mainly staying in Ghent. He tried to “transplant” North American inventions, and observed knowledgeably the political and religious conflicts of bilingual, biethnic, and bireligious Belgium. Like Sisyphus, he tried each day to re-establish himself financially, often starting from scratch the never-ending impossible task of making his fortune and paying back his creditors.

Dessaulles left Belgium a disappointed man and settled in Paris in February 1878. He still hoped to recover his fortune through some idea or invention. But it was only the money sent to him quite regularly by his son-in-law Frédéric-Ligori Béique* that enabled him to subsist. Life in Paris nevertheless had compensations: courses at the Collège de France, “free” music in the churches. These small pleasures did not save him from having to pawn a suit. Isolated from family and friends, the old man died on 4 Aug. 1895, after 20 years in exile.

At the news of his death, an anonymous writer – possibly Arthur Buies* – who was asked by Le Réveil of Montreal for a “truthful” article on Dessaulles, noted that he was a man of conviction, devoted to a cause for which he had sacrificed everything, but also “the victim of all kinds of pipe dreams” and the representative of “the most progressive and at the same time the most impractical tendencies” of the Liberal party. This seems to be an accurate assessment. In fortune, social influence, or family ties, his was a life that turned out badly. Here was a man, blessed with many advantages and talents, who played for high stakes and lost.

In addition to the works mentioned in the biography, Louis-Antoine Dessaulles is the author of Galilée, ses travaux scientifiques et sa condamnation; lecture publique faite devant l’Institut canadien (Montréal, 1856); Discours sur l’Institut canadien, à la séance du 23 décembre 1862, à l’occasion du dix-huitième anniversaire de sa fondation (Montréal, 1863); La guerre américaine, son origine et ses vraies causes; lecture faite à l’Institut canadien, le 14 décembre 1864 (Montréal, 1865); “Discours d’inauguration,” Institut canadien, Annuaire (Montréal), 1866: 17–26; À Sa Grandeur Monseigneur Charles Larocque, évêque de St. Hyacinthe (s.l., 1868); “Discours sur la tolérance,” Institut canadien, Annuaire, 1868: 4–21; “L’affaire Guibord,” 1869: 5–50; “L’Index,” 1869: 51–136; Dernière correspondance entre S.E. le cardinal Barnabo et l’Hon. M. Dessaulles (Montréal, 1871); La grande guerre ecclésiastique; la comédie infernale et les noces d’or; la suprématie ecclésiastique sur l’ordre temporel (Montréal, 1873); Quelques observations sur une averse d’injures à moi adressées par quelques savants défenseurs des bons principes (Montréal, 1873); Réponse honnête à une circulaire assez peu chrétienne; suite à “La grande guerre ecclésiastique” (Montréal, 1873); Ses difficultés avec Mgr. Bourget, évêque de Montréal, à propos de “La grande guerre ecclésiastique” et le journal “La Minerve” (s.l., 1873); Les erreurs de l’Église en droit naturel et canonique sur le mariage et le divorce (Paris, 1894); “Polémique entre l’Hon. A. B. Routhier, M. L. Fréchette et l’Hon. L.-A. Dessaulles, 1871–1872,” Auguste Laperrière, Les guêpes canadiennes (2v., Ottawa 1881–83), 2: 146–62.

Much of what Dessaulles wrote for newspapers can be located by consulting Jeannette Bourgoin, “Louis-Antoine Dessaulles, écrivain” (mémoire de ma, univ. de Montréal, 1975), and Harel Malouin, “Louis-Antoine Dessaulles (1818–1895),” Danielle Leclue et al., Figures de la philosophie québécoise après les troubles de 1837 (Montréal, 1988), 143–223.

AAQ, 210A, XXIX: 611, 614. ACAM, 901.133, 901.135. ANQ-M, CE2-5, 31 janv. 1818, 4 févr. 1850; P-102. ANQ-Q, E4, lettres envoyées, M-90, 1875: 38; E17/9, no.1238; E17/15, no.1100; E17/23, nos.1179, 1247, 1250; P-60; P-417 (some of which was published in Joseph Papineau, “Correspondance de Joseph Papineau (1793–1840),” Fernand Ouellet, édit., ANQ Rapport, 1951–53: 165–299, and in Julie Bruneau, “Correspondance de Julie Bruneau (1823–1862),” Fernand Ouellet, édit., ANQ Rapport, 1957–59: 53–184); P1000-30-562; P1000-49-960 (partly published in L.-J.-A. Papineau, Journal d’un Fils de la liberté, réfugié aux États-Unis, par suite de l’insurrection canadienne, en 1837 (2v. parus, Montreal, 1972– )). Arch. de l’évêché de Trois-Rivières (Trois-Rivières, Qué.), Corr. Laflèche, 1868. Arch. du séminaire de Saint-Hyacinthe (Saint-Hyacinthe, Qué.), A, Fg-6, dossier 1. Arch. municipales, Paris, État civil, 6 août 1895. Bibliothèque nationale du Québec (Montréal), Dép. des mss, mss-101, Coll. La Fontaine, lettres 343, 358, 404, 409, 659. McCord Museum, Dessaulles family. NA, MG 24, B2; B4; B59, note-book, 1852–74; MG29, D27. Can., Prov. of, Legislative Assembly, App. to the journals, 1858, app.28; Legislative Council, Journals, 1856–63. Charte et règlements de la cité de St-Hyacinthe . . . (Saint-Hyacinthe, 1895). Mandements, lettres pastorales, circulaires et autres documents publiés dans le diocèse de Montréal depuis son érection (20v., Montréal, 1869–1952), 6: 38–49. Règlements du conseil de ville de St-Hyacinthe . . . (Saint-Hyacinthe, 1856). Le Réveil (Montréal), 17 août 1895. Ivanhoë Caron, “Inventaire des documents relatifs aux événements de 1837 et 1838, conservés aux Archives de la province de Québec,” ANQ Rapport, 1925–26: 163, 191, 217–18. Yvan Lamonde et Sylvain Simard, Inventaire chronologique et analytique d’une correspondance de Louis-Antoine Dessaulles (1817–1895) (Québec, 1978). Bernard, Les Rouges. C.-P. Choquette, Histoire de la ville de Saint-Hyacinthe (Saint-Hyacinthe, 1930); Hist. du séminaire de Saint-Hyacinthe. Mario Coderre et al., Histoire de Saint-Dominique, 1833–1983 . . . (s.l., 1983). Harel Malouin, “Le libéralism de Louis-Antoine Dessaulles: une question,” Objets pour la philosophie, sous la direction de Marc Chabot et André Vidricaire (2v., Québec, 1983–85), 2: 111–52. Maurault, Le collège de Montréal (Dansereau; 1967). Gérard Parizeau, Les Dessaulles, seigneurs de Saint-Hyacinthe; chronique maskoutaine du XIXe siècle (Montréal, 1976). Jean Piquefort [A.-B. Routhier], Portraits et pastels littéraires (3v., Québec, 1873). Pouliot, Mgr Bourget et son temps, vol.4. Philippe Pruvost, “La philosophie devant le libéralisme: sur une polémique,” Objets pour la philosophie, 1: 209–26. Philippe Sylvain, “Libéralisme et ultramontanisme au Canada français: affrontement idéologique et doctrinal (1840–1865),” The shield of Achilles: aspects of Canada in the Victorian age, ed. W. L. Morton (Toronto and Montreal, 1968), 111–38, 220–55. Harel Malouin, “Le libéralisme: 1848–1851,” La Petite rev. de philosophie (Longueuil, Qué.), 8 (automne 1986): 59–101. Christine Piette-Samson, “Louis-Antoine Dessaulles, journaliste libéral,” Recherches sociographiques (Québec), 10 (1969): 373–87. Philippe Sylvain, “Quelques aspects de l’antagonisme libéral-ultramontain au Canada français,” Recherches sociographiques, 8 (1967): 275–97; “Un disciple canadien de Lamennais: Louis-Antoine Dessaulles,” Cahiers des Dix, 34 (1969): 61–83.

Cite This Article

Jean-Paul Bernard and Yvan Lamonde, “DESSAULLES, LOUIS-ANTOINE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/dessaulles_louis_antoine_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/dessaulles_louis_antoine_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Jean-Paul Bernard and Yvan Lamonde |

| Title of Article: | DESSAULLES, LOUIS-ANTOINE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | March 1, 2026 |