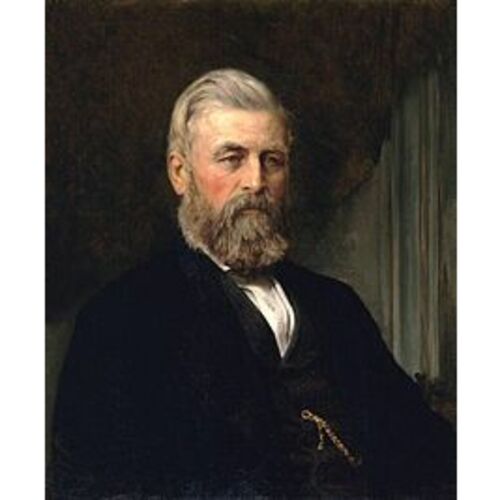

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

GIBSON, ALEXANDER, lumberman, railway entrepreneur, and industrialist; b. likely 1 Aug. 1819 in or near St Andrews, N.B., son of John Gibson and Jane Neilson; m. 31 Dec. 1843 Mary Ann Robinson of St James Parish, N.B., and they had three sons and four daughters, as well as several children who died young; d. 14 Aug. 1913 in Marysville (Fredericton).

Alexander Gibson’s mother, a lady of gentle birth from northern Ireland, was disowned by her family when she married and emigrated, in 1818, to Charlotte County, N.B., with her husband and his parents. By 1821 the extended Gibson family had moved to Oak Bay on the road between St Andrews and St Stephen (St Stephen-Milltown) where, in 1826, they were living in a log house and had six acres of land fenced and under crop. Gibson’s tales of his youth told of the poverty and hardships of pioneering; as a boy of 12 he had hewn shingles by hand and carried them into St Andrews on his back in order to help his mother to buy a cow. Either at the local school or from his mother and grandmother he learned to write brief, clear instructions in a firm, not uneducated hand and to sing the songs of Robbie Burns and Tom Moore, as well as to enjoy the works of Shakespeare.

He grew into an exceptionally tall and powerful man, a red-bearded giant of “very striking” appearance and “fine bearing,” an obituarist noted, able to dominate others by his physical appearance and with a desire to excel in everything he touched. When well past middle age he would boast that “there was nothing in connection with the lumber business that he could not do better than any man he employed.” Starting initially as a labourer, he moved on to become a skilled sawyer and then manager in water-powered sawmills in Milltown, since called “the most strikingly industrialized landscape in the province.”

By 1847 he had acquired a modest property, and over the next decade he came to be described in land records as “millman,” “lumberman,” “merchant,” and “yeoman,” this last designation indicating that by his mid thirties he had added farming to his other activities, but his particular strength lay in his mastery of the skills needed to manage water-power and exploit the new technology of gang saws introduced in Milltown in the 1840s.

In December 1854, in partnership with Samuel T. King, a merchant and lumberman from Calais, Maine, he leased “sawmills, machines, water power and water privilege” on the Lepreau River from William Kilby Reynolds, “the finest and fastest mill in the province” according to a later writer. This partnership had ended by 1862 when, early in the American Civil War, King sent agents to appraise mill and timber properties on the Nashwaak River near Fredericton owned by Robert Rankin* and his associates, Francis Ferguson and Allan Gilmour*. He decided not to purchase but Gibson, recognizing that a series of failures at the site had been due to mismanagement, moved there from Lepreau in the autumn of 1862. He paid £7,300 for assets in which the Rankin interests claimed to have invested nearly five times that sum. At the end of the first year of operation he was able to pay off a promissory note for £4,500 and thus to acquire outright ownership of a domain that included sawmills and grist mills, water rights, houses, a farm, a store, and 7,000 acres of prime spruce land. Edward Jack, a young St Andrews lawyer, became Gibson’s chief timber cruiser, surveyor, and adviser. Over the following decade Gibson acquired 30,000 acres of crown land on the upper Nashwaak and purchased other properties including 93,000 acres of forest land from the New Brunswick and Nova Scotia Land Company tract. Half of the crown land was granted by the anti-confederate government of Albert James Smith* in 1866.

Even before the legal details of his initial purchase were settled, Gibson had sent cutting crews into the woods and begun to enlarge the millpond’s log-holding capacity by building a chain of piers in the river extending two miles above the dam. By doing this, as well as building secondary dams and clearing out tributary streams, he was able to ensure a continuous flow of wood when the sawing of deals began in 1863. By that time he had brought skilled millhands and millwrights from Lepreau and had completely renovated the Rankin mills; they handled three-fifths of an estimated 40 million board feet in his log drive that spring.

Newly sawn deals dropped directly into the river and floated to a boom at its mouth, where a village grew up bearing the name of Gibson (now part of Fredericton). There, across the Saint John River from the provincial offices and legislature, they were loaded onto lighters or rafts and taken to Saint John for shipment to Liverpool or, on occasion, transfer to small schooners that sailed straight to American ports. In time a tannery and leather manufacturing company supplied belting and harness and a shipyard turned out woodboats and larger vessels, including two barques and four schooners for the American coastal trade. His brother John managed the shipyard as well as a number of other family enterprises. Many relatives followed Gibson to the Saint John valley, among them his brother-in-law and close associate Thomas Robinson, who acquired his own mill at Lower St Marys.

When he had first arrived at Rankin’s mills Gibson had found a community with typhoid endemic and the buildings filthy. To clear the site several houses were burned and a contaminated well filled in. He and his chief carpenter, Samuel Butler, then built a new village, named Marysville in honour of his eldest daughter, who died in 1867, and of Mrs Gibson, who may well have been the inspiration for its planning. Among the many new houses were 24 double tenements, the White Row, on the far bank of the river, with access to the mills by a footbridge. Public needs were met by a new school and a large new store with a capacious upper-storey hall which also served as a Methodist meeting-house until January 1873, when an elaborate new church was dedicated. This “little edifice,” standing on a hill overlooking the Anglican cathedral in the valley two miles away, was described by a correspondent for the Toronto Globe as “probably as fine a specimen of pure Gothic as can be found in America, and it is as chaste in ornamentation as it is beautiful in design.” Gibson paid the salaries of the minister and the organist, and gave an annual gratuity to members of the choir.

His own home, erected within three years of his arrival, had the character of a Victorian manor-house, vernacular Gothic, two and a half storeys, with a ballroom, guest rooms, and spacious grounds tended by an English gardener, “quite a palatial residence,” said a former Charlotte County neighbour. From there, within sound of the water-wheels and gang saws, his influence reached out into the political arena, where he actively supported Smith’s anti-confederate government, and, after confederation, became a valued supporter of provincial governments and of the federal Liberals. The hospitality of the Gibson household was a feature of the welcome extended to distinguished visitors to the provincial capital, from Governor General Lord Dufferin [Blackwood*] and Lady Dufferin in 1873 to Edward Blake in 1881 and Sir John A. Macdonald* and Lady Macdonald [Bernard] in 1887.

Gibson was a director of the Fredericton Railway Company, incorporated in 1866, and a member of the group which incorporated the New Brunswick Railway Company in 1870. When the promoters of the latter company, Henry George Clopper Ketchum* and John James Fraser*, failed in attempts to raise capital in England, Gibson promised to finance a quarter of the project and assumed the presidency in 1872. The company received 1,647,772 acres of crown land, 10,000 acres per mile, for building and operating a narrow-gauge railway on the eastern bank of the Saint John River. This “Gibson Line” reached Edmundston in 1878, with spur lines to Fort Fairfield and Caribou in Maine and bridges across the Saint John at Woodstock, Perth (Perth-Andover), and Grand Falls. The interchange with river traffic was at Gibson, where the company had a roundhouse, machine shops, and a freight yard.

In 1880 he and Isaac Burpee* negotiated a deal with George Stephen*, the representative of a syndicate which bought the company for around $2 million, of which Gibson’s share was about $800,000. He returned to railroading in 1882, when he and Jabez Bunting Snowball* were the leading figures in reviving the Northern and Western Railway Company of New Brunswick and in building a line from Gibson to Chatham, near the mouth of the Miramichi River. He used this railway to integrate a tannery at Millerton and lumber mills at Blackville with his Nashwaak enterprises and Saint John shipping company.

At Marysville he had installed new water-wheels and machinery in 1876 and by 1885 had added a steam-powered mill to produce laths and clapboards, a new shingle mill, and another sawmill to his industrial complex. But his attention became primarily focused on planning and carrying to completion the most grandiose project of his life, the building of one of the largest cotton mills in Canada directly across the Nashwaak River from his mansion. It was to test to the utmost his great practical imagination, formidable energy, genius for attending to details, and skill at political manipulation.

The main building, designed by A. H. Kelsey of the Providence, R.I., firm of Lockwood and Green, has been described by A. J. H. Richardson as being “architecturally more than just a very huge building for its day . . . something that seems to have been very new in industrial design, part of a new direction from the horizontally-stressed other great mills that had just preceded it.” It was 418 feet long, 100 feet wide, and four storeys high, lighted throughout by 800 electric lights (the first to be installed in the Fredericton area), heated by steam, and protected from fire by a sprinkler system. A dye house and five-storey ell to serve as a warehouse were added a few years later.

Apart from the posts and beams, which were fashioned from southern hard pine, almost all of the basic building materials came from his own lands. Expert workmen from Ontario directed one of the largest brickyards in Canada, where clay dug up on site was moulded into bricks, which in turn were laid under the direction of Captain Kelsey Mooney of Saint John. Women were to constitute two-thirds of the mill’s workforce; a brick hotel for single women was erected near at hand, and brick houses, most of them double tenements, filled the fields behind White Row and extended up the hillside to the edge of the woods.

Gibson’s political connections and his potential for influencing both provincial and federal elections in York were of great value in overcoming formidable transportation problems, for there was no railway to the site and no bridge of any kind across the Saint John River between Saint John and Woodstock. In 1884 the New Brunswick government, under his political ally Premier Andrew George Blair*, began the construction of a road bridge at Fredericton and in the same year the Northern and Western Railway, with subsidies from both the provincial and the federal governments, opened the Gibson to Marysville section of its line to the Miramichi. In 1887–88 Gibson was associated with the Fredericton and Saint Mary’s Railway Bridge Company, which constructed a steel bridge between Fredericton and Gibson. Ostensibly this was part of a promised extension of the federally built “Short Line” intended to serve Halifax, but it was the only part actually built. When he became a cotton manufacturer Gibson transferred his support to the protectionist party. Thomas Temple, the Conservative mp for York, was a central figure in the bridge company.

Machinery began to arrive from New England in 1884. At the height of the spring freshet that year a schooner, assisted by a tugboat, made its way to Marysville, the first occasion on which anything larger than canoes and small boats had ventured up the shallow and fast-flowing Nashwaak. In mid August a train, running over a roadbed that had not been ballasted, opened the railway by carrying up three carloads of freight. The first raw cotton arrived at the end of April 1885. A great twin-cylinder 1,300 horsepower engine was then set in motion; it was to provide power for the cotton mill for the next 46 years. To celebrate the start-up, “the Boss” gave a dinner in the mill on Boxing Day 1885, attended by more than 1,000 of his employees and their families. The fare was on a heroic scale: one turkey for every four persons with vegetables, fixings, plum pudding, rich pastries, oranges, apples, and grapes. By November 1889 the mill, employing around 500 women and men, was in full production. High wages and good housing had attracted experienced supervisors and skilled factory hands from England, the United States, and other parts of Canada as well as workers from the local countryside.

Already it was obvious that there were too many cotton mills in Canada, and two of the largest, both producing coloured cotton, were in New Brunswick: Gibson’s and the somewhat larger Saint Croix Cotton Mill at Milltown, of which James Murchie* was president. When in 1886 Montreal interests organized a trade association in an attempt to restrict production, Gibson refused to join and his competition severely injured the Saint Croix mill. He did join in 1888 but his provincial rival, facing bankruptcy, reduced prices in order to sell off its inventory. He then did the same and the association disintegrated. Four years later, when Andrew Frederick Gault* and David Morrice of Montreal incorporated the Canadian Colored Cotton Mills Company Limited, the Gibson enterprise, while retaining its own corporate structure, agreed to market its entire output through the new organization.

At the height of his career Gibson employed up to 2,000 persons at times in his various enterprises; there were winters in which he had more than 600 horses at work in woods operations. He was producing about one-third of the provincial output of lumber and his lumber exports in some years constituted more than half of the export commerce of Saint John. By 1897, though he continued to be a major exporter, only half of the wood was coming from his ageing mills and good logs were becoming scarce on his lands, for over the decades he had taken more than 600 million feet from the Nashwaak watershed.

In addition, the inadequacy of the financial underpinning of his business empire was also becoming apparent. The Gibson Leather Company, to which he had lent $40,000, had got into difficulties in 1884 and he paid a further $10,000 to take it over. In 1889 creditors became uneasy over the Northern and Western Railway, of which he was general manager. A rise in the price of deals and small lumber enabled Gibson and Snowball, the chairman, to survive the crisis and the company was reorganized as the Canada Eastern Railway Company in 1890. In 1893 he acquired full ownership after a quarrel with Snowball had led the Boss to boycott the line, reopening an old road and using horses to move freight between Marysville and Fredericton.

In 1888 his holdings, apart from the railway, had been incorporated into a limited company, Alexander Gibson and Sons Limited, with a capital of $3 million assigned mainly to himself but with small portions allotted to his sons, brother, and sons-in-law. Ten years later this company, in addition to owning almost all of the town of Marysville and other manufacturing plants elsewhere, held more than 180,000 acres in freehold property and crown timber licences on a further 110,000 acres. In 1898 it was merged with the railway company, becoming the Alexander Gibson Railway and Manufacturing Company, which acquired a further 28,000 acres when the New Brunswick and Nova Scotia Land Company was liquidated in 1899. The funded debt of the new company consisted of a $2-million trust mortgage and a second mortgage of $1.75 million, both in 30-year bonds. These were held by the Bank of Montreal and by Gibson’s Liverpool agents, David Jardine and Peter Owen, timber merchants and brokers who carried on business under the name of Farnworth and Jardine.

In all its legal manifestations the Gibson enterprise was an old-fashioned family concern dependent on the banks for working capital, with a patriarchal head who was contemptuous of banking rules and regulations and given to arbitrary decisions which made it impossible for the bookkeepers to keep track of affairs. Its substance was summed up by Frank M. Merritt, a clerk who became Gibson’s son-in-law; in the conclusion to a letter apparently intended for journalists preparing an article around 1889, he wrote: “Gentlemen please take partners for the next waltz and don’t forget to mention that Alex Gibson owns the whole business. For heaven’s sake don’t show this to anybody.” In 1902 the Halifax financial house of John Fitzwilliam Stairs*, with young William Maxwell Aitken* acting as one of its agents, attempted to make an audit of affairs. They proposed to recapitalize the company at $6 million but the old man, with his “long white beard and long black shoes” reminding Aitken of Buffalo Bill and Brigham Young, refused to relinquish his personal authority. The trustees for the bondholders were temporarily appeased in 1904 when the sale of the Canada Eastern to the Canadian government enabled the company to retire bonds of a par value of $800,000, and three years later Hugh Havelock McLean*, acting on their behalf, began to tidy up the company’s affairs.

In July 1907 David Morrice discharged a $1.75 million mortgage held by Jardine and Owen and in return received title to the cotton mill property, which included houses and water rights on the east bank of the Nashwaak; this was transferred in 1910 to the Canadian Colored Cotton Mills Company. The remaining assets of Alexander Gibson Railway and Manufacturing were conveyed to his Liverpool creditors the following year. All that remained to Gibson was a pension of $5,000 a year and a lifetime right to the use of his residence; his children retained only modest properties, though Charles H. Hatt, a son-in-law, continued to be manager of the cotton mill until 1913.

Throughout his life he was a man apart who marched to his own drummer. No one in the history of the province ever matched him in gaining private possession of crown land, yet in 1874 he offended his fellow lumber barons by coming to the rescue of the provincial government in its attempt to restore stumpage duties on wood cut on crown land. When lumbermen in the northeast, who unlike those in the south did not control extensive freeholds, refused to participate in an auction of timber limits, Gibson stepped in and acquired a number of choice lots. They then agreed to pay the fees. He may have planned to expand but it is just as likely that his intervention was a friendly gesture to John James Fraser, then provincial secretary and receiver general, with whom he had been associated in the battle against confederation as well as in business.

Gibson’s reserved and dignified manner seems to have hidden a complex inner life. In 1880–81 he suffered an emotional crisis. This came when the sale of the New Brunswick Railway had given him, for perhaps the only time in his life, a large sum of ready money; it had also led to an invitation to join a syndicate being formed by Sir William Pearce Howland* to build the railway to British Columbia. While these events were unfolding, he had to cope with a series of deaths in his immediate family: his father in July 1880, his eldest son, John Thomas, in October, and one of John Thomas’s daughters and his only son in February 1881. The death of his eldest son occurred just 13 years after the death of his eldest daughter, Mary Ann, had led an obituarist in the Provincial Wesleyan of Halifax to refer to “a severe ordeal to the spirit of piety” which she had had to endure as a result of the family’s accession to wealth and social position. The sudden death of John Thomas must have revived memories of that earlier loss. Gibson had disapproved of his eldest son’s excessive drinking, and stories were told of a bitter confrontation in which John Thomas had had the temerity to suggest that it was time for the Boss to retire.

This was almost certainly the time of “sore trial” from which Gibson afterwards said he was delivered through the help of Edward Blake, the leader of the Liberal party, who advised him to give attention to those in need: “For as you minister to those people your burden will be lessened and gradually disappear, it was the Master’s way.” Already over 60 years of age he found an outlet for his benevolence in his cotton mill project.

This new Gibson stands in contrast to the earlier hard-driving entrepreneur who, though considerate of his workmen and generous, notably so in his display of support for Methodist churches, was not distinguished for his gentleness. Describing the later Gibson, Martin Butler, the radical editor and poet, wrote: “There has never been a case of necessity, or a calamity, brought to his notice in which Mr. Gibson did not . . . go down deep into his pockets to alleviate; and were the capitalists of the United States as considerate for the welfare of their employees . . . there would not be the strikes, strife, and bloodshed that is now happening.” But the competitive spirit and stubborn pride were still there, pushing him to outdo his old neighbours on the St Croix River by creating an industrial society in this unlikely corner of the Canadian forest. If his charity was unlimited, his tolerance was not. He continued to control the content of sermons preached in the Marysville Methodist church (he had an aversion to the mention of the fires of hell) and he still proscribed the sale of alcohol in the town, authoritarian behaviour which led a young Acadian millhand, Louis Joseph King, to deride him as “a kind of Protestant pope.”

His domestic life, apart from his break with his eldest son, seems to have provided a happy refuge from the outer world. His second son, Alexander Jr, was a competent lumberman but lacked the leadership qualities of his father and elder brother. To his daughters and younger surviving son, James, the Boss was an overindulgent father. James shared his father’s concern for the workers and the poor and his love of providing them with picnics and entertainments. He built a covered skating-rink, sponsored hockey and baseball teams, organized a brass band, bought a merry-go-round, and had nearly completed a racetrack when the family’s fortune ran out. In 1900 Alexander Jr, “Young Sandy,” was selected as the Liberal candidate and elected as member of parliament for York; Liberals happily reclaimed the Boss as one of their own who had wandered temporarily from the fold. He died peacefully at his home on 14 Aug. 1913, two weeks after his 94th birthday.

Marysville, still recognizably his town, is now incorporated into Fredericton. The cotton mill continued in production for more than four decades after his death and the building survives, a national historic site restored as government offices with a larger-than-life statue of the Boss in the foyer. Charles Henry Lugrin, founder, proprietor, and editor of the Fredericton Daily Herald from 1882 to 1892, a newspaper closely identified with Gibson especially in its early years, gave this summary of his character: “A very shy man . . . [he] appeared to live in a world apart from others. . . . Beneath his stern . . . exterior, this keen and indefatigable business man hid the soul of a poet. . . . Some men loved him; many men esteemed him; more men feared him; no man understood him. He probably did not even understand himself.”

Some details of Alexander Gibson’s life were obtained in discussions with Hannah Lane, Gail Campbell, and T. William Acheson.

Carleton Land Registry Office (Woodstock, N.B.), Registry books (mfm. at PANB). Charlotte Land Registry Office (St Andrews, N.B.), Registry books (mfm. at PANB). NA, RG 31, C1, 1851, St David Parish, N.B.; St Stephen Parish, N.B. (mfm. at PANB). N.B. Museum, Gibson, Alexander, cb; Weldon and McLean records. Northumberland Land Registry Office (Newcastle, N.B.), Registry books (mfm. at PANB). PANB, RS9, 1884–86, 1897–98; RS17, esp. A; RS22; RS108; RS272; RS624. Private arch., Karen Blair (Toronto), Memoir by R. J. Kaine and other papers collected for a projected genealogy of the Gibson family; J. M. Burden (Fredericton), Memoir by H. M. Young and other papers on the history of Marysville. Univ. of N.B. Library, Arch. and Special Coll. Dept. (Fredericton), Essay case 11d, no.11 (Francine Pelletier and Ruth Coghlan, “Marysville: a study of Alexander Gibson’s influence on its architectural and social development,” typescript, 1975). York Land Registry Office (Fredericton), Registry books (mfm. at PANB). Capital (Fredericton), 1881–87. Daily Colonist (Victoria), 15 Aug. 1913. Daily Gleaner (Fredericton), various dates. Edward Jack, “A bit of history: the development of the Nashwaak,” St. John Daily Sun (Saint John), 15 March 1895: 2. New Brunswick Reporter and Fredericton Advertiser, 31 Aug. 1881: 2 (citing the Toronto Globe). Provincial Wesleyan (Halifax), 1867, continued as the Wesleyan, 1880. Semi-Weekly Mail (Fredericton), 15 Aug. 1913. T. W. Acheson, “The National Policy and the industrialization of the Maritimes, 1880–1910,” Acadiensis (Fredericton), 1 (1971–72), no.2: 3–28. Can., Parl., Sessional papers, 1885, no.37: 174–97; Royal commission on the relations of labour and capital in Canada, Report (5v. in 6, Ottawa, 1889). Canada investigates industrialism: the royal commission on the relations of labor and capital, 1889 (abridged), ed. G. [S.] Kealey (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 1973). Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898). Census records, 1851–1861–1871–1881, Saint Marys, York County, New Brunswick, comp. G. C. Bidlake (Fredericton, 1983). Anne Fox, “Marysville cotton mill an exemplary historical industrial site in North America” (report prepared for N.B., Dept. of Supply and Services, Queenstown, April 1985; copy in contributor’s possession). T. G. Loggie, “How stumpage was started in New Brunswick . . . ,” Canada Lumberman (Toronto), 50 (1930), no.18: 25–26. N.B., Acts, various dates. Our dominion; historical and other sketches of the mercantile and manufacturing interests of Fredericton, Marysville, Woodstock, Moncton, New Brunswick, Yarmouth, N.S., etc. (2v. in 1, Toronto, 1889). F. H. Phillips, “Boss Gibson . . . ,” Canadian Magazine, 86 (July–December 1936), no.5: 16, 30–31. D. D. Pond, The history of Marysville, New Brunswick (Fredericton, 1983). S. G. Rosevear, “Alexander ‘Boss’ Gibson: portrait of a nineteenth century New Brunswick entrepreneur” (ma thesis, Univ. of Maine, Orono, 1986). W. A. Squires, History of Fredericton: the last 200 years, ed. J. K. Chapman (Fredericton, 1980). The wood industries of New Brunswick in 1897 ([Fredericton], 1969) [republishes the N.B. section of The wood industries of Canada (London, 1897), with a new introduction].

Cite This Article

D. Murray Young, “GIBSON, ALEXANDER,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 28, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/gibson_alexander_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/gibson_alexander_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | D. Murray Young |

| Title of Article: | GIBSON, ALEXANDER |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | December 28, 2025 |