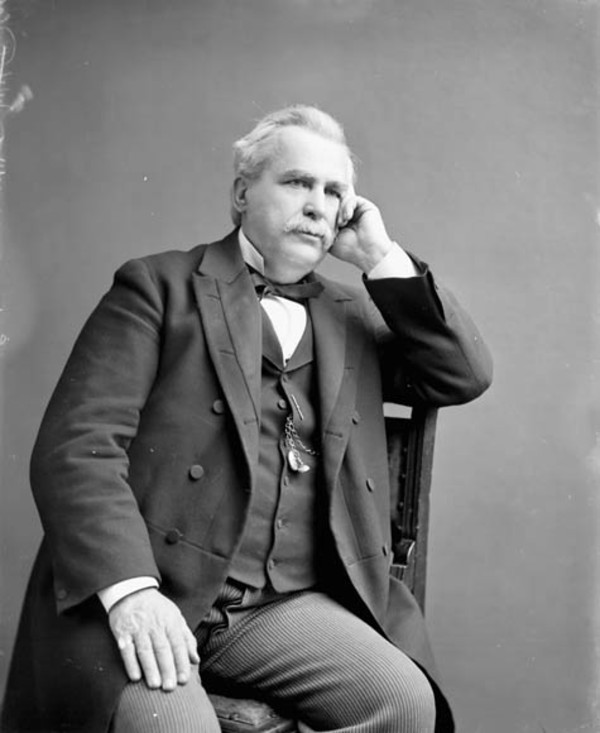

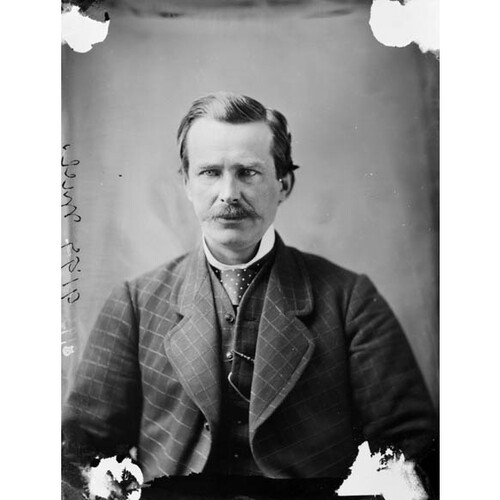

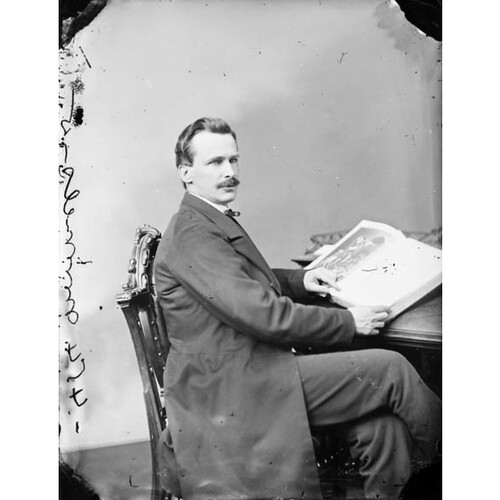

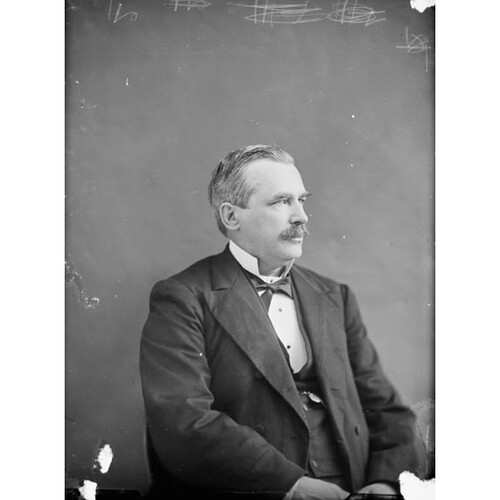

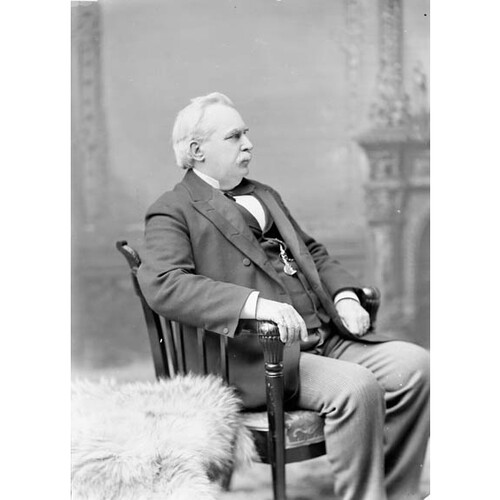

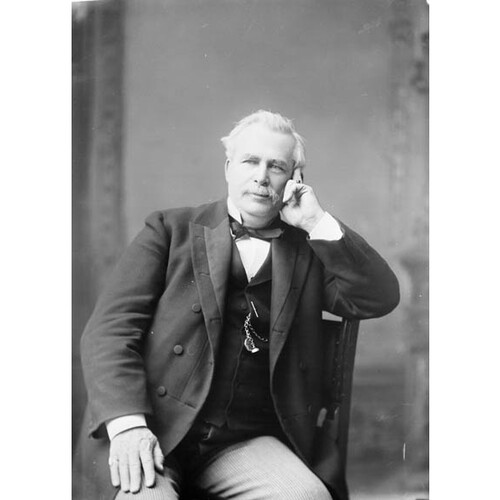

MILLS, DAVID, teacher, office holder, farmer, lawyer, politician, journalist, author, and judge; b. 18 March 1831 in Orford Township, Upper Canada, son of Nathaniel Mills and Mary Guggerty; m. 17 Dec. 1860 Mary Jane Brown in Chatham, Upper Canada, and they had three sons and four daughters; d. 8 May 1903 in Ottawa and was buried in Palmyra, Ont.

David Mills’s father, a native of New York State, and his mother, from County Cavan (Republic of Ireland), moved from Nova Scotia to Upper Canada, settling on the Talbot Road west in Kent County about 1818. David received his early education at the local common school, in Palmyra Corners. The school suffered from indifferent teaching, poor facilities, and a transient student body, but Mills did well and, showing promise, apparently received some private instruction as well. He subsequently became a teacher, and from April 1856 to April 1865 he served as a school superintendent (inspector) in Kent. During this period he also farmed (he inherited part of the family farm at Palmyra), read extensively, and through occasional speeches and newspaper articles – one of his topics was the Reciprocity Treaty – began to develop a public profile. By 1864 he seems to have become active politically in the Reform party in Kent.

Following his stint as school superintendent, Mills enrolled at the University of Michigan Law School, from which he graduated in March 1867. His decision to attend an American law school was certainly unconventional; had he been principally interested in practising law in Upper Canada it could even be considered bizarre, since the Law Society of Upper Canada treated American legal training as if it were no training at all. In fact, Mills seems to have been in no hurry to enter practice. The problems of accreditation aside, he made no formal application to the law society until 1878, was not called to the bar until 1883, and even then practised only intermittently, first in the London, Ont., firm of Ephraim Jones Parke* and later with one of his own sons. In 1885 he was on the faculty of the newly opened London Law School as professor of international law and the rise of representative government. Five years later he became a qc.

Mills’s main ambition was to enter politics, and in this respect his training at Michigan under Thomas McIntyre Cooley and others proved extremely useful. Cooley, one of the leading legal intellectuals in the United States and an expert on constitutional law, appears to have been especially influential in shaping Mills’s understanding of federalism. At a time, following the Civil War, when the American model of federalism was being equated in Canada with instability and anarchy, Cooley introduced Mills to the theory of classical federalism and showed him how legislative power could be constitutionally divided between two levels of government, each “sovereign in a qualified sense.”

Upon his return to Canada in 1867, Mills secured the Reform nomination for the federal constituency of Bothwell, which covered parts of Kent and Lambton counties. In the dominion’s first election, which brought Sir John A. Macdonald* and the Conservative party to power, he won a narrow victory. He would hold the seat until 1882 and again from 1884 to 1896. Mills took strong exception to Macdonald’s view that, by the terms of the British North America Act, the provincial governments were subordinate to the central government. Drawing upon Cooley, he quickly established himself in the House of Commons as a defender of provincial rights. On 20 Nov. 1867 he introduced a motion to do away at the federal level with the practice of dual representation, which allowed a person to represent a federal and a provincial constituency simultaneously, on the grounds that it compromised provincial independence. After repeated attempts, he succeeded in having dual representation abolished in 1873. He also advocated reform of the Senate to render it a better guardian of provincial interests, suggesting in 1872 that senators be popularly elected or chosen directly by the provincial legislatures. Soon after confederation Mills had begun to glimpse the dangers inherent in the federal power of disallowing provincial legislation; as early as 1869 he argued that “the veto power was one which no government should possess.” Holding that confederation was essentially a “compact” among the provinces, he took a dim view of the Macdonald government’s expansive interpretation of federal jurisdiction under section 91 of the BNA Act. His reading of the division of powers was from the first highly decentralist. Indeed, Mills told parliament in June 1869 that if ever it was “a question whether Federal or Local Legislatures should be destroyed,” his view was that “the country would suffer far less by the destruction of the Federal power.”

Thanks in part to interventions of this sort, Mills gained a reputation as one of the most capable members of the federal Liberal caucus. His star rose steadily. Mills’s provincialist reading of the BNA Act was essentially similar to the view propounded by Oliver Mowat, the Liberal premier of Ontario from 1872 to 1896, with whom he established an abiding friendship. Mowat was evidently impressed with Mills’s grasp of the legal foundations and political significance of provincial power, and in 1872 he asked him to prepare a written defence of the province’s placement of its disputed western and northern boundaries. The report, published in early 1873, made Mills a key player in the boundary dispute; he continued thereafter to press Ontario’s case against the federal government both in and out of the commons, even when his own party was in power in 1873–78 under Alexander Mackenzie*. As economic conditions worsened in Canada in the mid 1870s, Mills was asked in January 1876 to chair the select committee established to investigate the depression. He used the committee’s report to advertise his views of the virtues of free trade, and he warned that the costs of imposing tariffs far outweighed the benefits of such artificial stimulation.

Fresh from his excursion into fiscal policy, in October Mills was appointed minister of the interior. The office included responsibility for a broad range of issues relating to settlement and self-government in the North-West Territories, as well as Indian affairs. Mackenzie later praised Mills for being “always willing and effective” as a minister, although in the crucial question of extending self-government in the northwest he seems to have been cautious to a fault. He was reluctant, for instance, to remove from the North-West Territories Act of 1875 restrictions on the organization of municipalities and school districts.

The defeat of the Mackenzie government in the election of 1878 put an end to Mills’s ministerial duties and administrative ambitions. Having retained Bothwell, however, he was one of the senior Ontario Liberals in the caucus, and he used his position behind the scenes and in parliament to advantage. Mills was a “Blake man” and was apparently one of the leaders of the movement in 1880 to oust Mackenzie from the party leadership. When Edward Blake* assumed the position, Mills became one of his chief lieutenants in the house. He helped to lead the attack against the Conservatives’ National Policy [see Sir Samuel Leonard Tilley*], coordinated the Liberal filibuster of the electoral franchise bill in 1885, and continued to attack the Macdonald government’s centralism. Mills considered that his speech of 1 April 1885, criticizing the factory bill proposed by Darby Bergin* as an invasion of provincial jurisdiction, was among the finest of his parliamentary career.

Nor was Mills’s censure of the Tories confined to parliament. As editor-in-chief of the London Advertiser from 1882 to 1887 [see John Cameron (1843–1908)], he built a case against the Macdonald government’s administration of national affairs in a series of unsigned, but distinctive, editorials, which alternated between partisan screed and law-school lecture. He seems to have been particularly active as a journalist in 1883, when, because of his disputed defeat in the election of 20 June 1882, he was forced to sit out a session of parliament while his case was considered by the courts. He won in February 1884 and returned to the commons, but the editorials he had produced the previous year – especially those excoriating Macdonald’s use of disallowance – remain among the richest political commentaries of the era.

Mills’s turn as a journalist did little to harm his reputation as a man of deep partisan feeling. Yet, as sectional issues came increasingly to dominate national politics in the late 1880s, he often found himself at odds with other Liberals. In 1886 he followed Blake in condemning the execution of Louis Riel* and with Blake supported Philippe Landry*’s motion of regret against Mackenzie, Sir Richard John Cartwright*, John Charlton, and other leading Ontario Liberals. At the time of the controversy in 1889 over the Jesuits’ Estates Act, passed the previous year by the Quebec government of Honoré Mercier*, Mills delivered a strong speech opposing disallowance, arguing that parliament had no business interfering with legislation that was clearly within provincial jurisdiction. When he repeated the speech in his constituency, the Toronto Globe reprinted it but disassociated itself from his views. And in the 1890 debate over the use of French in the legislature and courts of the North-West Territories [see D’Alton McCarthy*; Alexandre-Antonin Taché*], Mills delivered an eloquent defence of linguistic rights, which again set him apart from many of his co-partisans. In the vote on justice minister Sir John Sparrow David Thompson*’s compromise proposal on language rights, which simply left the issue to the territorial legislature, Mills and Blake supported the motion while almost all other Liberals from southwestern Ontario went against it.

The tension between constitutional principle and party loyalty was most dramatically illustrated in Mills’s position over Manitoba’s abolition of public funding for Catholic schools [see Thomas Greenway]. Despite his commitment to provincial rights and his party’s opposition to remedial legislation, Mills believed that in principle the federal government was constitutionally obliged to restore the schools. In his draft speech on the question, written sometime in February or early March 1896, he argued that parliament had a duty “to restore a right taken away, and to keep faith with the minority” – a clear rebuke of Liberal leader Wilfrid Laurier*. Historian Donald J. A. McMurchy suggests that key members of the Liberal caucus, upon reading the draft, prevailed on Mills to take a position that was less hostile to the Liberal leadership. Whatever the reason, his speech to the house on 18 March was equivocal. Though he continued to maintain that the government was constitutionally bound to act, Mills now argued that the remedial bill proposed by the Conservative prime minister, Sir Mackenzie Bowell*, was poorly drafted and premature. On the 20th he voted with his party against it.

Damage apparently was already done, however, for though the Liberals won overall, Mills lost Bothwell in the general election of 23 June. He blamed his narrow defeat on “the treachery of the Roman Catholic clergy” and Denis O’Connor*, bishop of London. Sir John Stephen Willison*’s explanation seems more plausible: Mills was close enough to the Liberal position to fall from favour with some Catholic voters, yet sufficiently independent to alienate “extreme Protestants because he would not deny validity in the position of the minority,” and he evidently created just enough enemies to ensure his defeat.

Despite this set-back, Mills hoped to return to parliament, either in a by-election or by appointment to the Senate. Although summoned to the Senate in November 1896, he was not invited to join the cabinet, and he suspected in early 1897 that he had been the victim of “an intrigue in which Laurier was an assenting party and an instrument in the hands of men who bullied him.” He consequently devoted more time to his law practice in London, continued his work at the University of Toronto (where he had been appointed in 1888 to teach constitutional and international law), and wrote and lectured on a wide variety of religious and political subjects. His exclusion from Laurier’s government did not last long, however. When Sir Oliver Mowat resigned from cabinet, Laurier asked Mills to fill the vacancy. On 18 Nov. 1897 he was sworn in as minister of justice and he became government leader in the Senate.

Mills’s political reincarnation was deeply ironic. As a senator he found himself in an institution which had resisted his efforts at reform. As minister of justice he held the veto power over provincial legislation – and he exercised it rather freely, despite his earlier assertions that disallowance could not be squared with the federal principle. Nevertheless, he took his duties seriously, dispensed patronage as generously as possible, and used his annual reply to the speech from the throne as an opportunity to assess the state of the British empire, especially the progress being made towards the creation of an “Imperial constitution,” the term he used to describe an association resembling the modern commonwealth. Upon the death of justice John Wellington Gwynne in 1902, Mills, exercising his authority as minister of justice, arranged his own appointment as a puisne judge of the Supreme Court of Canada – a position that reputedly had been promised to him when he joined the cabinet in 1897. The appointment was roundly criticized by some in the legal press who noted that Mills had never been a judge, that he had limited experience in private practice, and that at age 70 he lacked the vigour to master the law, with which he was largely unfamiliar. In May 1903, scarcely more than a year after joining the court, Mills died suddenly of an internal haemorrhage. Survived by his wife and six children, he left no will.

Though David Mills was an important lieutenant in the Liberal party, he did not become a dominant force in Canadian politics. Personal factors clearly played some part in limiting his rise. He was close to Blake, but the opportunities for making his mark under Blake’s leadership were restricted by the Liberals’ failure to defeat Macdonald. Passed over when Blake stepped down in 1887, he was never close to Laurier. Indeed, according to Willison, “Mills never believed that Laurier was his intellectual equal while Laurier never believed that Mills was a practical or effective working political comrade.” Most commentators conclude, moreover, that Mills lacked a number of the characteristics typically associated with modern democratic leadership. He possessed little magnetism, spoke ponderously, tended to theorize at length, and could be, in the words of historian William Lewis Morton*, “compulsively pedantic.” That his contemporaries referred to him, not always kindly, as “the philosopher from Bothwell” (a title evidently coined by Macdonald) suggests that this impression was widespread.

Yet if Mills’s philosophic cast of mind proved a political liability, the same quality earned him a reputation as one of the ablest constitutional theorists of his generation, especially in the area of federalism. He made two crucial contributions to the theory and practice of Canadian federalism. First, he explained the meaning and implications of the federal principle at a time when the term was highly controversial and open to seriously divergent interpretations. Mills argued consistently that each of the levels of government defined by the BNA Act, the federal and the provincial, was supreme or sovereign within its own sphere but powerless to act beyond its constitutional jurisdiction. The practical upshot of this principle was that any attempt by the federal government to interfere in matters constitutionally entrusted to the provincial governments – through the use of the veto powers of reservation and disallowance, for example – was of dubious legitimacy.

Mills, of course, was not alone in explaining and defending this conception of provincial autonomy. The Mowat government in Ontario frequently protested against federal infringement upon provincial rights, and the interprovincial conference of 1887, organized by Mowat and Honoré Mercier, was intended to publicize and coordinate provincial dissatisfaction. Yet, with the possible exception of Blake, there was no mp who did more to articulate and popularize the language of provincial autonomy than Mills. It is a mark of the success of Mills and his associates in the provincial rights movement that even before their view had been sustained by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, a process that began with Hodge v. the Queen (1884) [see John Godfrey Spragge*], the constitutional principle of provincial autonomy and the concept of sovereign spheres of power had become standard terms in Canadian political discourse. Even Macdonald had been forced to adopt this language.

In the years following confederation, the problem of divining clear jurisdictional boundaries from the malleable words of the BNA Act produced a series of quarrels, in which the federal and provincial governments competed for the control of such matters as liquor licensing, resource development, and business regulation. Here Mills made his second contribution he developed one of the earliest and most elaborate provincialist readings of the act. In 1885, for example, he argued in the commons that, by the terms of the act, provincial governments had been given wide latitude to legislate on police matters, broadly defined as measures aimed at balancing individual liberty with the good order, health, and morality of the community. Conversely, he maintained that the federal power over trade and commerce ought to be interpreted narrowly, so as not to interfere with provincial self-government. Mills not only anticipated the jurisprudential trend within the JCPC in favour of provincial claims, but he correctly surmised that the provinces’ exclusive jurisdiction over property and civil rights would become the crucial legal category through which the provincial police power could be defined and defended.

In a broader political and constitutional context, Mills believed that the defence of provincial autonomy was integral to the fulfilment of liberal political principles in Canada. In the best Reform tradition, he argued that the provincial rights movement was simply defending the provinces’ liberty – their right to govern themselves – in much the same way that earlier reformers had defended home rule against imperial interference, representative government against the “family compact,” or parliamentary government against the rule of kings. Mills’s speeches and editorials are full of symbolic historical allusions that attempt to place the struggle for provincial rights against the backdrop of British and Canadian constitutional history.

Yet Mills was hard pressed to maintain a consistent position when provincial governments acted in ways that were clearly illiberal and when they deprived individuals of their rights. It was in such cases, notably involving minority language and education rights, that Mills’s positions were the most difficult personally, the most problematic politically, and the most tentative intellectually. He had enormous faith in the rule of law, especially in the ability of lawyers to find constitutional formulae that would satisfy both individual and collective aspirations. This was a common enough ideal among advanced Liberals of his era, but Mills’s attempts to realize it were particularly frank, expressive, and unstable. In struggling to reconcile provincial rights with individual rights, Mills personified the dilemmas of late-19th-century Ontario Liberalism.

[The main collection of David Mills’s papers and journals is in the Regional Coll. of the Univ. of Western Ont. Library (London). It includes a series of letters written in 1889 to his daughter Alice Maud Lovett Mills, which contain reminiscences of his youth; a transcript copy is available at the MTRL.

Mills gave speeches on a wide range of topics. His papers at Western include the unpublished texts of his talks on: “Abraham as a leader of a political revolution” (box 4280) (a pair of speeches that are half biblical exegesis, half moral tale about Abraham and his followers, who endured hardships in order to secure “the rights of conscience and the benefits of self-government”); “The higher criticism” (box 4280) (a vigorous defence of the “new” theology, including a natural explanation of miracles); “The English and the United States system of government compared” (box 4278) (a classic defence of British institutions and responsible government); “Henry George’s theory of property in land” and “Henry George’s theory of property in land and taxation” (box 4283) (a spirited critique); and “Sleep and its mysteries” (box 4280) (which includes a section on the meaning of dreams).

Many of Mills’s speeches on political topics and on matters of international and constitutional law were published. Listings are available in Canadiana, 1867–1900, CIHM Reg., and NA, Catalogue of pamphlets . . . , comp. Magdalen Casey (2v., Ottawa, 1932). His publications also include A report on the boundaries of the province of Ontario (Toronto, 1873); a revised version . . . for the purposes of arbitration between the Dominion of Canada and the province of Ontario (Toronto, 1877); and The English in Africa (Toronto, 1900). In addition, he published a number of articles in the Canadian Magazine, which reveal the diversity of his interests: “The evolution of self-government in the colonies: their rights and responsibilities in the empire,” 2 (November 1893–April 1894): 533–44 (a sort of heroic account of the British empire); “The missing link in the hypothesis of evolution, or derivative creation,” 3 (May–October 1894): 297–308 (a critique of Darwin’s theory of natural selection); “Saxon or Slav: England or Russia?” 4 (November 1894–April 1895): 518–30 (a plea, among other things, for Anglo-American solidarity against Russian imperialism); and “The new Monroe Doctrine of Messrs. Cleveland and Olney,” 6 (November 1895–April 1896): 365–80 (an analysis and critique of the doctrine as contrary to international law).

Finally Mills, who was apparently a Methodist, wrote much inspirational poetry, some of which was published; for example, Poems written at spare moments (Ottawa, 1901), a copy of which is preserved at Univ. of Toronto, Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library. Some of his poems, such as “I think I’m growing old,” published in the Globe, 13 Aug. 1898: 6, under the initials D. M., are essentially meditations on death. r.c.v.]

AO, RG 8, I-6-B, 23: f.18; RG 22, ser.354, no.4210. NA, RG 68, 476, liber 120: f.377. London Advertiser, 1882–87, esp. January–March 1883; 9 May 1903. Ottawa Evening Journal, 9 May 1903. Can., House of Commons, Debates, 1867–96; Parl., Sessional papers, 1867–96; Senate, Debates, 1897–1902. Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose and Charlesworth), vol.1. [F.] M. Greenwood, “David Mills and co-ordinate federalism, 1867–1903,” Univ. of Western Ontario Law Rev. (London), 16 (1977): 93–112. History of the county of Middlesex . . . (Toronto and London, 1889; repr., intro. D. [J.] Brock, Belleville, Ont., 1972). G. V. La Forest, Disallowance and reservation of provincial legislation ([Ottawa], 1955; repr. 1965). Fred Landon, “A Canadian cabinet episode of 1897,” RSC Trans., 3rd ser., 32 (1938), sect.ii: 49–56; “David Mills, the philosopher from Bothwell,” Willisons Monthly (Sarnia, Ont.), 5 (1929), no.3: 8–9. D. J. [A.] McMurchy, “David Mills: nineteenth century Canadian Liberal” (phd thesis, Univ. of Rochester, N.Y., 1968). Middleton and Landon, Prov. of Ont., 3: 77–79. W. L. Morton, “Confederation, 1870–1896: the end of the Macdonaldian constitution and the return to duality,” JCS, 1 (1966), no.1: 11–24 [Lovell Crosby Clark’s comments on this article, with Morton’s reply, appear in “Dialogue: David Mills and the remedial bill of 1896,” JCS, 1, no.3: 50–53]. Thomas, Struggle for responsible government in N.W.T. (1978). R. C. Vipond, Liberty and community: Canadian federalism and the failure of the constitution (Albany, N.Y., 1991). Willison, Reminiscences.

Cite This Article

Robert C. Vipond, “MILLS, DAVID,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 23, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mills_david_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mills_david_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Robert C. Vipond |

| Title of Article: | MILLS, DAVID |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | February 23, 2026 |