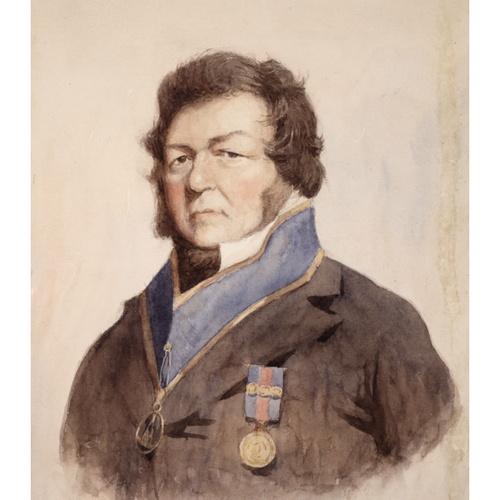

RIDOUT, THOMAS GIBBS, banker; b. 10 Oct. 1792 near Sorel, Lower Canada, third son of Surveyor General Thomas Ridout* and Mary Campbell; m. first on 5 April 1825 Anna Maria Louisa Sullivan (d. 1832) and had two sons and one daughter, and secondly on 6 Sept. 1834 Matilda Ann Bramley and had six sons and five daughters; d. 29 July 1861 at Toronto, Canada West.

Thomas Gibbs Ridout moved with his parents to Newark (Niagara-on-the-Lake) in 1792 and to York (Toronto) in 1797. He was educated by John Strachan at Cornwall and, when 17 years old, was appointed deputy to his father, then registrar of deeds for York County. He also worked as a temporary clerk in several government departments. In 1811, armed with letters of introduction from Lieutenant Governor Francis Gore*, Ridout travelled to England in the hope of beginning a business career in one of the great London trading houses. British commerce, however, was suffering because of the Napoleonic blockade of European ports; Ridout returned to Upper Canada at the outbreak of war with the United States, and entered the 3rd Regiment of York militia as a lieutenant. He was appointed a temporary clerk in the Commissariat Department, possibly through the influence of his father who had previously worked in the department, and in September 1813 served on the Niagara frontier. In January 1814 Ridout was promoted deputy assistant commissary general at a salary of £500 and stationed at Cornwall. Following the examples of nepotism set by his own father and other members of the small government clique at York, Ridout, within a month of his own appointment, procured as confidential clerk his 14-year-old brother John. During the remaining year of the war Ridout purchased supplies for the British forces on the upper St Lawrence, often from farmers and merchants in New York State. He remained with the Commissariat Department until 1820 when he retired on half pay. Probably while stationed at Quebec after the war, Ridout became enmeshed in the quarrel between his family and the Jarvis clan that led in 1817 to the duel in which Samuel Peters Jarvis* killed John Ridout.

T. G. Ridout was presented with an opportunity for civilian employment in 1821 when the Bank of Canada was incorporated by a group of government officers and York merchants. In January 1822 the bank’s shareholders unanimously elected him its first cashier, or general manager, at a salary of £200. Ridout, who had handled and disbursed large sums of money during the war, was an obvious choice for the post. He was accepted by the capital’s growing Tory clique because he was a member of one of York’s first families, and by the emerging political moderates because of his own liberal views and those of his family. Ridout was soon on his way to Philadelphia and London to learn what he could of current banking practices, and to purchase plates and paper. In the bank’s early years Ridout was an advocate of hard money policies and was backed by merchants such as John Spread Baldwin against government supporters such as the Boultons, the Robinsons, and John Strachan who wanted an easier credit system and a greater flow of paper currency. However, one suspects that Ridout played a largely passive role in implementing bank policy since no effort was made to oust him when proponents of easier credit gained control of the board of directors in 1825. Once established in his post as cashier Ridout began to assume his rightful place as a second generation member of York’s gentry. In 1824 he purchased from Andrew Mercer* for £500 his Sherborne estate on the northern edge of town, and in 1825 by his first marriage gained as brothers-in-law both Robert Baldwin* and Robert Baldwin Sullivan*.

The Bank of Upper Canada was considered by many in the 1820s and 1830s to be a virtual tool of the Family Compact. Ridout, testifying in 1835 before a select committee of the assembly, defended the bank’s record and claimed that “every farmer or person in trade or in respectable circumstances, who can give unexceptional personal security, has a right to secure from the public banks reasonable accommodation in proportion to his means, without being considered to ask for favours.” Its officers and directors of course interpreted the terms “respectable circumstances” and “reasonable accommodation,” and the bank became a frequent target of radical reform criticism. William Lyon Mackenzie’s hatred of the Tory institution was so intense that in December 1837 he interrupted his march down Yonge St to Toronto to burn the house of Dr Robert Charles Horne*, chief teller of the bank and brother-in-law of its first president, William Allan*. Ridout for his part served from the beginning of the rebellion until the end of April 1838 as a captain in the Bank of Upper Canada Guard, a militia unit created solely to protect the bank and its coffers from rebel attack. Late in 1838 the tension generated by the Patriot attack near Prescott once more turned the bank into a fortress which temporarily held Ridout’s family and that of R. B. Sullivan. But the bank survived the troubles of 1837–38 without incident and within a few months Ridout was giving more thought to the winter’s assemblies and balls than to its physical defence.

The 1840s were for T. G. Ridout, now entering middle age, a period of increasing civic involvement. In 1841 he chaired the electoral committee supporting Reformer Isaac Buchanan*’s successful bid to represent Toronto in the assembly. Initiated as the first recruit of the St Andrew’s Masonic Lodge in 1823, Ridout was provincial grand master by 1846. He was also involved in Toronto’s St Andrew’s Society, rising from second vice-president in 1843 to president in 1848–49 and 1849–50. He was the first president of the Toronto Mechanics’ Institute upon its incorporation in 1847. In the same year Ridout, along with such Toronto notables as William Botsford Jarvis and Joseph Clarke Gamble, founded the Toronto, Hamilton, Niagara, and St Catharines Electro-Magnetic Telegraph Company. He was as well treasurer of Trinity College for a short time before his death.

In 1850 the Bank of Upper Canada became the official government bank; soon both Ridout and the institution he represented were deeply enmeshed in the politics of railways and Ridout as well began to speculate in land. In 1852 he was an incorporator of the Grand Trunk Railway and, along with Peter* and Isaac Buchanan, of the Hamilton and Toronto Railway Company, an eastern extension of the major Buchanan enterprise, the Great Western Railway. At the same time Ridout tried unsuccessfully to persuade Peter Buchanan, then residing in Glasgow, to become the bank’s London agent. In the following year the bank accepted the account of the Great Western, and Ridout’s eldest son Thomas became, probably not coincidentally, an assistant engineer on that railway. Within a month T. G. Ridout received from Isaac Buchanan 40 shares of Great Western stock, enough to qualify him to become a director. The accommodation was not without its awkward moments, however; in 1854 Ridout was concerned because news of the bank’s large loans to the Great Western seemed likely to lead to an effort in the legislature to force the government to remove its account. When this step was taken for other reasons two and a half years after Ridout’s death, it was a major factor precipitating the bank’s collapse.

Although the bank was becoming increasingly the subject of criticism and legislative inquiry, Ridout’s personal fortune continued to improve. In 1853 his salary as cashier was raised from £750 to £1,000. Swept up in the speculative boom which preceded the depression of 1857, he estimated his Sherborne property to be worth £16,000, or £20,000 if subdivided, and was considering selling it although he was “in no hurry about it.” When he did sell this land, a month before his death, he received $9,500 for it. He was also in 1853 developing several hundred acres near Port Hope. He had two streets laid out and planned to sell the 76 building lots for £30 to £35 each. He estimated that another 100 acres north of the town could be developed into one-acre properties worth £100 each. He also owned 100 acres “on the lake shore and harbour . . . where the Grand Trunk rail way is to be” and he estimated its worth at four to five times that of the land north of the town. He even confided to his wife that, after selling all this property, “I fancy I shall not bother myself any more about the Bank [of Upper Canada].” His grandiose plans were disrupted by the end of the speculative boom in 1857, and in his will he left the modest sum of $4,160.

The depression of the late 1850s adversely affected the fortunes of the Bank of Upper Canada as well as those of its cashier. Like many of his contemporaries Thomas Gibbs Ridout was unable to cope with the new economic situation; in addition, his health began to fail in the late 1850s. In April 1861 he retired in favour of the younger financier, Robert Cassels*, who admitted in his first report that the bank had suffered losses of $1,500,000, or half its capital, as a result of imprudent railway and land speculations. Ridout’s health continued to deteriorate and he died at Toronto on 29 July 1861.

PAC, MG 24, D16, 52; RG 8, I (C series), 1171, p.20; 1203, p.215. PAO, Ridout papers. York County Surrogate Court (Toronto), will of Thomas Gibbs Ridout, 3 Nov. 1860; inventory of estate, 21 Sept. 1861. Can., Prov. of, Statutes, 1847, c.81; 1852, c.44. Ten years in Upper Canada in peace and war, 1805–1815; being the Ridout letters . . . , ed. Matilda [Ridout] Edgar (Toronto, 1890). Town of York, 1793–1815 (Firth). Town of York, 1815–34 (Firth). U.C., House of Assembly, Journal, 1835, app.iii. Globe, 30 July 1861. Toronto directory, 1837–56. One hundred years of history, 1836–1936: St. Andrew’s Society, Toronto, ed. John McLaverty (Toronto, 1936). R. M. Breckenridge, “The Canadian banking system, 1817–1890,” Canadian Bankers’ Assoc., Journal (Toronto), II (1894–95), 105–96, 267–366, 431–502, 571–660. E. C. Guillet, “Pioneer banking in Ontario: the Bank of Upper Canada, 1822–1866,” Canadian Banker (Toronto), 55 (1948), 115–32.

Cite This Article

Robert J. Burns, “RIDOUT, THOMAS GIBBS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 8, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/ridout_thomas_gibbs_9E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/ridout_thomas_gibbs_9E.html |

| Author of Article: | Robert J. Burns |

| Title of Article: | RIDOUT, THOMAS GIBBS |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1976 |

| Year of revision: | 1976 |

| Access Date: | March 8, 2026 |