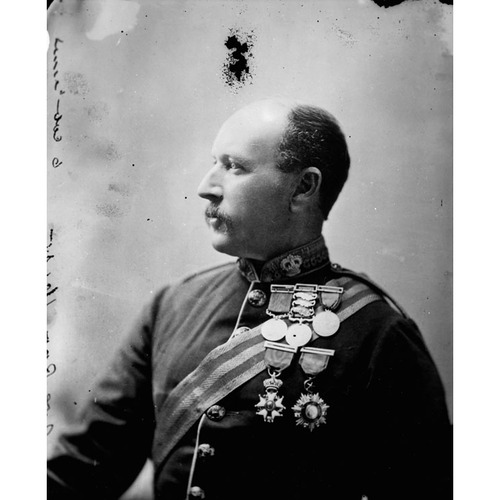

ROBERTSON-ROSS, PATRICK, soldier and adjutant-general of the militia; b. 19 May 1828 in Scotland, second son of Lord Patrick Robertson, judge and wit, and Mary Cameron Ross; m. in 1851 Amelia Ann Maynard, and they had at least one son; d. 23 July 1883 at Boulogne, France.

Patrick Robertson was educated in Edinburgh before enlisting as a corporal in the Capetown Rifles at 19; he was commissioned as an ensign on 7 April 1848. After seeing active service in the Kaffir wars, Robertson fought with distinction in the Crimean War where he was appointed aide-de-camp to Major-General Sir William Eyre. When Eyre came to Canada in 1856 to command the British forces, Robertson, now brevet major, again served as his adc, from 29 July 1856 to 1 May 1858, although he was on half pay from 3 April 1857. He returned to Britain in 1858 but was back in Canada in 1864, as a brevet lieutenant-colonel, for duty against the Fenians. When his uncle, General Hugh Ross, died on 24 June 1864, Robertson inherited his uncle’s property in Scotland and changed his name to Robertson-Ross. He purchased a lieutenant-colonelcy, on 6 May of the next year, and returned to duty with depot battalions in England.

Robertson-Ross’s experience in training militia at depots in Britain and connections he had made in Canada may account for his half-pay appointment on 9 May 1869 as adjutant-general of the Canadian militia. Sir George-Étienne Cartier*, the first minister of militia and defence, facing the Fenian threat and the impending withdrawal of the imperial garrison, had introduced the Militia Act of 1868. The act authorized a levée en masse, a general levy in order to establish a reserve militia, which necessitated the registration of all able-bodied males between the ages of 18 and 60, as well as 8 to 16 days training annually for 40,000 volunteers in an active militia. If insufficient numbers came forward for the active militia the authorities could resort to the ballot to acquire the required strength. By the time Robertson-Ross arrived, a Canadian deputy adjutant-general, Lieutenant-Colonel Walker Powell*, had set up the active militia and had arranged for the selection of its officers in each regimental district (which coincided with electoral districts) as well as for the continuation of their training in schools of military instruction associated with the British garrison, as had been done in the Province of Canada.

In his first annual report Robertson-Ross compared the structure created by Canada’s Militia Act with the systems that had produced victories for the North in the American Civil War and for Prussia in the Austro-Prussian War. Recalling his own experience in South Africa, he recommended that Canadian cavalry be trained as mounted infantry and he also warned against a reduction of the permanent-staff brigade-majors, the key officers in the militia system. The new system was tested early during Robertson-Ross’s tenure when he armed some militia units and the gunboats on the Great Lakes because of threats of Fenian raids in October 1869 and the following April. That month he was also called upon to furnish 750 militia to accompany Colonel Garnet Joseph Wolseley* and British regulars sent to suppress the Red River rebellion [see Louis Riel]. Lieutenant-General James Alexander Lindsay*, who had come to Canada to arrange the evacuation of the British garrison and who organized the expeditionary force, reported that if Robertson-Ross had been left to himself it would have been only “half equipped.” The militia’s role in the western campaign and its success in checking Fenian raids in 1870 without the aid of the British garrison, which was being concentrated in Quebec for the withdrawal, encouraged Robertson-Ross to assert that Canada had “solved the problem of how to create a reserve force.” Since, he said, an adjutant-general was only a staff officer required to carry out details of drill, discipline, and command under a general officer commanding an army, and the militia was now Canada’s army, he recommended that his appointment be upgraded to a major-general and a goc. Although Cartier was apparently willing to promote him, Lindsay reported adversely on him to the War Office and the proposal was then dropped by Sir John A. Macdonald*. In 1871 Robertson-Ross established permanent artillery batteries at Kingston and Quebec which were intended to act as schools of gunnery for the militia. Further competence was demonstrated by the force in 1871 when a small contingent proceeded to Upper Fort Garry (Winnipeg) without British aid. Yet, with the Fenian threat reduced, one-quarter of the militia volunteers throughout the country failed to re-enlist.

Robertson-Ross’s annual report for 1872 provides a detailed account of the state of the militia. It also includes a description of his overland journey to British Columbia, travelling on Canadian soil and accompanied only by his 16-year-old son and a few guides. At Fort Garry he arranged for the militia uniform to be changed from green to red as a reassurance to the Indians who had trusted the British regulars. He commented on the problems created by whisky smuggling and horse stealing among the Indians and recommended a force of 550 soldiers as well as a chain of military posts for the territories rather than just a civil police force. In British Columbia he made arrangements for the establishment of a militia. This report shows that despite his reassurances he was concerned with the response to the militia generally; in Quebec, for instance, some units did not drill in 1872 and though he praised the militia spirit of the French Canadians he admitted the ballot might be needed in some districts. He met with Macdonald in December to discuss his findings and in the spring of 1873, after his report was published, legislation was introduced providing for judicial institutions in the territories but also for an armed force which was to become the North-West Mounted Police.

When Robertson-Ross’s patron, Cartier, died in 1873, the adjutant-general promptly applied for more “active service” and returned to depot duty in England and then in Scotland; in 1880 he retired as a major-general. A new governor general, Lord Dufferin [Blackwood*], had arrived in Canada almost a year before Robertson-Ross left; he at first reported on him favourably but then said he was inefficient. The governor noted gossip that Robertson-Ross had owed his position to Cartier’s penchant for his attractive wife, and he told the colonial secretary that Robertson-Ross had had to be peremptorily ordered by Sir John Young* not to hang Fenians summarily. However, the artillery schools he had set up, his proposals for the expansion of training that foreshadowed the opening of the Royal Military College of Canada in Kingston in 1876, and his recommendation for the creation of a general-officer-commanding, a post held by his successor, Major-General Sir Edward Selby Smyth, show that Robertson-Ross knew what was needed in Canada. But an officer who had risen as a result of early front-line leadership and later because of useful connections with powerful military and civilian leaders was not fitted to carry through major military reforms; yet his more senior successors, with higher status and rank, were little more successful.

Patrick Robertson-Ross was the author of “Report of a reconnaissance of the north-west provinces and Indian territories of the Dominion of Canada . . . ,” Royal United Service Institution, Journal (London), 17 (1873): 543–67.

Can., Dept. of Militia and Defence, Report on the state of the militia (Ottawa), 1868–75. Gentleman’s Magazine and Hist. Rev. (London), 197 (January–June 1855): 194; 217 (July–December 1864): 392–93; 218 (January–June 1865): 632. DNB (entry for Patrick Robertson). Hart’s army list, 1853–83. Desmond Morton, Ministers and generals, politics and the Canadian militia, 1868–1904 (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 1970).

Cite This Article

Richard A. Preston, “ROBERTSON-ROSS, PATRICK,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 11, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/robertson_ross_patrick_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/robertson_ross_patrick_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | Richard A. Preston |

| Title of Article: | ROBERTSON-ROSS, PATRICK |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1982 |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | March 11, 2026 |