Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

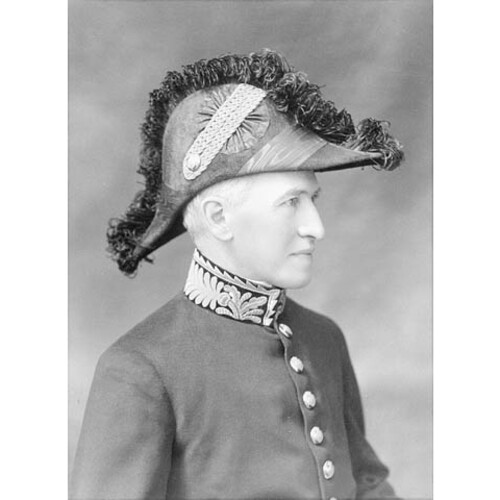

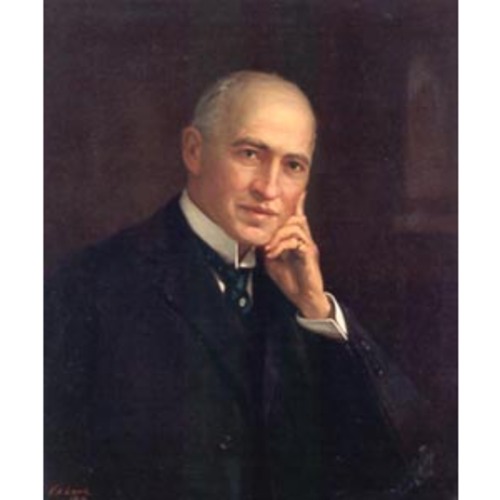

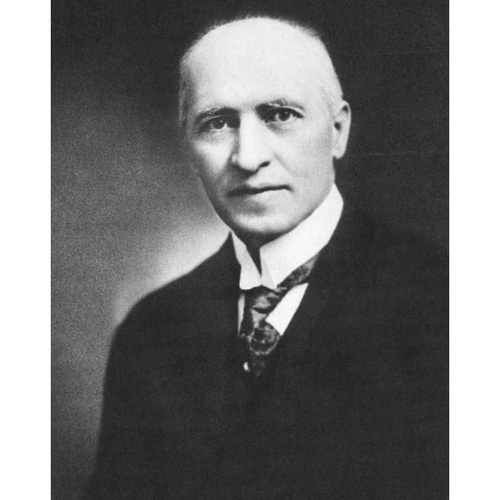

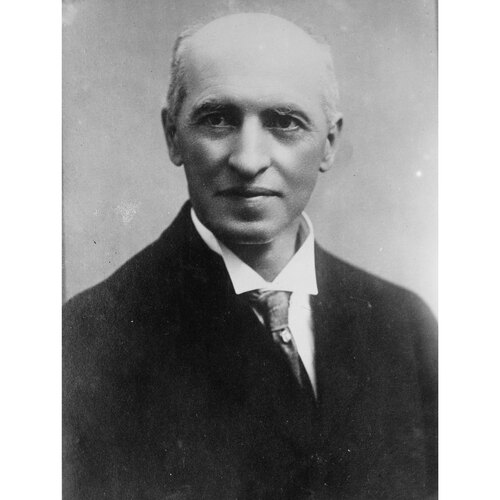

SIFTON, ARTHUR LEWIS WATKINS, politician, lawyer, and judge; b. 26 Oct. 1858 in St Johns (Arva), Upper Canada, son of John Wright Sifton and Kate Watkins; m. 20 Sept. 1882 Mary Horsman Deering in Cobourg, Ont., and they had one daughter and one son; d. 21 Jan. 1921 in Ottawa.

Arthur Lewis Sifton’s father was the son of Anglo-Irish Protestant immigrants to Canada; his mother was born in Ireland and immigrated with her parents. John Wright Sifton was by turn a farmer, a land speculator, an oilman, and a railway contractor. This peripatetic career meant that Arthur was educated in a variety of schools across southern Ontario, including a boys’ school at Dundas and the high school in London. The family moved to Manitoba in 1875 to permit J. W. Sifton to take up contracts for telegraph and railway construction in the expanding west. Arthur completed high school in Winnipeg before he and his younger brother, Clifford, were sent in 1876 to Victoria College, a Methodist institution in Cobourg, Ont. Though evidently capable of intellectual brilliance, Arthur was by no means a disciplined student. Rather like his father, he was restless and impulsive, happily skipping classes while confident of his own ability to pass, choosing to broaden his mind in other ways. His fellow students awarded him a prize for being “intellectually, morally, physically and erratically preeminent in virtue and otherwise, especially otherwise.” Following his graduation with a ba in 1880, Arthur began to article in the Winnipeg law office of Albert Monkman, a career path from which he was soon temporarily diverted.

Arthur had inherited from his father a commitment to Methodism and to temperance. Prominent in the Dominion Alliance for the Total Suppression of the Liquor Traffic, J. W. Sifton in 1880 was a leader of a campaign in the federal constituencies of Lisgar and Marquette to bring into effect the local option provisions of the Canada Temperance Act of 1878. Arthur addressed at least 16 meetings in the successful campaign for votes, but the victory eventually was lost to a legal challenge.

In 1881 J. W. Sifton moved to Brandon, hoping to take advantage of the boom in real estate caused by the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway in western Manitoba. Arthur quickly abandoned his law books and joined his father in the scramble for profits. Though officially he presided over a Brandon branch of Monkman’s law firm, he had not qualified for independent practice. In addition to speculating in real estate, he was active in the temperance movement and in organizing a loan company. He also was elected as an alderman to Brandon’s first city council, on which he served two terms, in 1882 and 1883. On 20 Sept. 1882 he married Mary H. Deering; their first child, Nellie Louise, would be born the following August. Perhaps the prospect of becoming a father turned his attention to the need to complete his legal training: in the spring of 1883 he passed his barrister’s examinations, though not those for attorney, and was called to the Manitoba bar; in June he became a full-fledged partner in his brother’s law firm, now Sifton and Sifton. In addition to his service in civic politics, Arthur was elected to the school board, and he was active in the Reform Association, the Brandon Agricultural Society, and the Literary Society of the local Methodist church. Briefly in 1884 he even considered running for mayor, but he concluded that he had insufficient support.

Yet, despite all this success and apparent prospects for the future, in 1885 he removed with his family to Prince Albert (Sask.), dissolving the partnership of Sifton and Sifton. He was made a notary public that year and was enrolled as an advocate in 1886. Why he made the move is unclear. Prince Albert once had had high hopes of being on the main line of the transcontinental railway, but it was facing a more constrained future by 1885, since the CPR was being built far to the south. While making useful political connections and writing for the local newspaper, Sifton found time to earn his ma from Victoria College and his llb from the University of Toronto, both in 1888. He moved to Calgary, apparently because of his wife’s health, the following year. There he established a practice on Stephen Avenue, was appointed qc in 1892, and served at least some time in the office of the city solicitor. He later joined the firm of Sifton, Short, and Stuart and acted as crown prosecutor. In February 1898 his second child, Lewis Raymond St Clair, was born.

During this time his brother had remained in Brandon, building his law practice, speculating successfully in western Manitoba lands, and becoming attorney general of Manitoba in 1891 and minister of the interior in the federal government of Wilfrid Laurier* in November 1896. As interior minister, Clifford was responsible in the cabinet for the whole of western Canada, and in this capacity he relied heavily upon Arthur for advice about the welfare of the Liberal party in the Calgary region and for other services, such as settling a difficult election protest in Prince Albert. Arthur, meanwhile, plied Clifford with suggestions about patronage issues in Calgary and Banff. He did not hesitate to put himself forward. As early as August 1896 he had suggested that the North-West Territories needed a chief justice for its Supreme Court and that a promotion from the existing bench would open up a vacancy for which “there is no one else in the Territories eligible except myself.” No court appointment could be made immediately, but Clifford managed from time to time to throw an occasional plum to Arthur, such as a retainer for a coroner’s inquest in 1897. Finally, Arthur decided once more to take the plunge into politics, challenging the popular and long-time member for Banff, Dr Robert George Brett, a Conservative, in the territorial elections of 1898. At first Sifton thought he had won by a majority of 36, but after a series of court challenges to the validity of some of the votes, Brett was declared the victor in 1899 by a margin of two. Sifton in turn successfully protested Brett’s election, on the basis of corrupt practices, and he won the ensuing by-election in June 1899. Named president of the Alberta Liberal Association that year, he actively supported the federal Liberals in the dominion election of 1900. The pay for being an mla was small, however, and Arthur told his brother that the law business, both civil and criminal, was very slow. Clearly he wanted something more remunerative.

Clifford was able to oblige: early in 1901 he chose James Hamilton Ross*, commissioner of public works and treasurer for the North-West Territories, to be Yukon commissioner; on 1 March the territorial premier, Frederick William Gordon Haultain*, appointed Arthur Sifton to succeed Ross. The federal government had granted to the territories full responsible government in 1897; however, the annual federal grant had failed utterly to keep up with the rapid growth of population and demand for facilities and infrastructure there. This problem fuelled a strong demand for provincial autonomy, a movement championed by the Haultain ministry. Arthur Sifton took up the cause as soon as he entered office, asking for supplementary grants to meet unforeseen expenses and then going to Ottawa with Haultain to seek better financial terms and eventual autonomy. He was re-elected with a large majority in 1902.

At this point, yet another career beckoned. As early as September 1901 his brother had proposed the chief justiceship of the territories to him. Arthur had thought it best not to accept, having just taken up his ministerial duties, but made it clear that he would like the post in the long run. He obtained it in January 1903, when the court’s first chief justice, Thomas Horace McGuire, retired. Sworn in on the 13th, Sifton occupied the position until 16 Sept. 1907, when he became chief justice of the Supreme Court of the new province of Alberta. As had been the case when he joined the territorial government, his appointment was denounced by the Conservative press as the most crass form of nepotism. The malign hand of Clifford Sifton, rather than merit, was seen to be behind it. Yet Arthur was indeed very able, and took on an exceptionally heavy workload; by July 1903 he was able to tell Clifford, “I like the work better than I anticipated and most people appear to be satisfied now.” In recognition of his service the University of Alberta would confer a dcl on him on 13 Oct. 1908.

Although he remained centred in Calgary, Sifton regularly heard cases in the southern territories from Maple Creek (Sask.) west to Cardston and Pincher Creek (Alta), and on occasion went north to Red Deer and Edmonton. Sifton appears to have had a severely practical approach to the law, and there is no indication in studies of his judicial career that he established important new points of law or precedents. He was a difficult personality for lawyers to read: he sat impassively smoking his trademark cigar; some thought him cynical in expression, others sphinx-like. He recorded by hand in notebooks the essence of each case that he heard, along with his decision. He was famed for his “rapid-fire methods” on the bench, frequently offering instant judgements in cases of considerable complexity which might have taken many days to argue. Most common among the cases which he heard in the early years were charges of horse and cattle rustling and other forms of theft, burglary, false pretences, forgery, disputes over money owed, and various other issues concerning property. Typically, cattle rustlers were sentenced to three years’ hard labour. Occasional cases of incest, assault, or attempted murder arose, but they were a small fraction of the total. Efficient Sifton may have been. Yet, notes one authority, when his decisions were appealed, “his brethren had difficulty in ruling on them because he rarely provided reasons for his judgments.”

Very likely Sifton expected to continue in this position until his retirement. Politics, however, intervened decisively. In February 1909 the premier of Alberta, Alexander Cameron Rutherford*, announced a modestly expansionist policy to encourage the construction of new and branch railway lines; among them was a plan to support the building of the Alberta and Great Waterways Railway northeast from Edmonton to Fort McMurray. On the basis of this policy the Liberal government was re-elected by a large majority in 1909. However, when the new legislature met in February 1910, a scandal concerning the generous financial terms promised to the A&GW exploded with stunning unexpectedness: William Henry Cushing, minister of public works and the representative of Calgary in the cabinet, resigned, followed within a few weeks by William Asbury Buchanan, a minister without portfolio. A significant minority of Liberals supported these ministers. In the interim the attorney general, Charles Wilson Cross, under attack for his part in the A&GW agreement, also resigned, though he soon returned to the front bench. To try to save his government, Rutherford in mid March appointed a royal commission comprising three justices of the Supreme Court, chaired by Nicholas Du Bois Dominic Beck, to investigate the A&GW contract and the charges of corruption and incompetence. Thereupon the house adjourned until 26 May, when it expected to have a report to consider.

Lieutenant Governor George Hedley Vicars Bulyea, a Liberal partisan who worked closely with Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier on the matter, realized in February that the divided Liberals would demand “a scapegoat” and that since there was no obvious successor to Rutherford of any strength, salvaging the Liberal government in the province likely would mean seeking a replacement outside the existing legislature. “Possibly Chief Justice only permanent solution,” he telegraphed to Laurier in mid March. By 17 May Sifton had agreed; when the house met on the 26th, Bulyea announced Rutherford’s resignation, Sifton’s appointment as premier, and – to the consternation of the opposition – the prorogation of the legislature, to give Sifton time to select a new cabinet and consolidate his position. C. W. Cross told Laurier, “The result of the acceptance of the Premiership by the Chief Justice is that the family quarrel in the Liberal party here is at an end.” At the end of June Sifton and his cabinet were sustained in a series of by-elections, Sifton sitting for the constituency of Vermilion. In addition to his posts as premier and president of the Executive Council, he was provincial treasurer and minister of public works from 1 June 1910 to 4 May 1913 and minister of railways and telephones from 20 Dec. 1911 until his resignation in 1917.

The new premier needed to establish his credentials, first with the divided and somewhat sceptical mlas, and secondly with the populace at large. He was neither dynamic nor robust: he had had some sort of heart affliction for most of his life, which left him few reserves of energy. This fact was not widely understood, with the result that he often was perceived as lazy. He also spoke far less than most prominent politicians, and was distinctly reserved in public. One historian has described his manner as “glacial and arbitrary.” That he had a clear, incisive mind few doubted. With respect to his reputation amongst the public, he was helped by circumstance: Laurier in 1910 made one of his few appearances in the west, and his first extensive sounding of western public opinion in more than 15 years. He invited Sifton to join him for the Alberta leg of his tour; appearing on the platform with the popular prime minister and some of his leading cabinet ministers not only was a statement of solidarity and support from the foremost Liberals in the country, but brought the premier to the attention of his people as no other event could have done. This triumph was followed in 1911 by Sifton’s strong endorsement of the federal Liberal policy of reciprocity with the United States. Freer trade with the Americans was highly popular in Alberta, and it gave Arthur Sifton an opportunity to emerge clearly from the shadow of his brother Clifford, who was one of the policy’s most formidable opponents.

For many Albertans, however, the major question in local politics was how the premier would extract the province from the mess created by the A&GW contract. Late in 1910 Sifton introduced legislation to wind up the railway company and to seize from the banks the proceeds, totalling some $7,400,000, of the bonds sold on its behalf. He was strongly opposed within his own party by Cross (so much for Cross’s sentiments concerning unity in the Liberal family). When the banks refused to turn the money over, the province sued them. Since the province had guaranteed the bonds and interest at five per cent, the bondholders did not suffer, but during the litigation the money was not constructing one foot of railway. At first it looked as though the province might win: in 1911 Charles Allan Stuart of the Supreme Court of Alberta found in its favour; the following year the federal minister of justice, Charles Joseph Doherty*, refused to act on a petition for disallowance of Sifton’s legislation, and the Supreme Court in banc dismissed an appeal from Stuart’s decision. The Royal Bank of Canada then appealed directly to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, which in January 1913 found that the legislation was beyond the powers of the province. What might have been a crushing blow to the government proved not to be so serious. For one thing, late in 1911 Sifton had announced a new and extensive policy of railway construction, including a plan to build an alternative to the A&GW; by the time of the Privy Council decision substantial building had taken place and there was considerable optimism in the province about the future. For another thing, Sifton in 1912 brought Cross into the cabinet as attorney general, thus partially healing the Liberal rift. Finally, the ablest Conservative and de facto leader of the opposition, Richard Bedford Bennett*, had been elected to the federal parliament in 1911. There is little doubt as well that a redistribution (or gerrymander) of seats worked decisively in the government’s favour. In the 1913 general election the Liberals took 38 seats, to 18 for the Conservatives.

Yet another reason for the Liberal victory was Sifton’s assiduous cultivation of the farm vote. The United Farmers of Alberta [see James Speakman*] was becoming a powerful political pressure group: both the Liberals and the Conservatives were anxious to be seen to be supportive of the farmer. Sifton and his minister of agriculture, Duncan McLean Marshall*, had the advantage of being in power and able to deliver on their promises. The 1913 session of the legislature, just before the election, was called by Liberals the “farmers’ session.” Three agricultural schools were established, including one in Sifton’s riding of Vermilion. The Alberta Farmers Co-operative Elevator Company Limited was incorporated [see Edwin Carswell*], and another act provided for the organization of cooperatives. The Direct Legislation Act introduced referenda and popular initiation of legislation under certain conditions. The historian Lewis Gwynne Thomas notes that these and other acts “all . . . had been foreshadowed in the resolutions of the convention of the U. F. A. in January, 1913.” The reality was, according to Thomas, that most Albertans were alienated from, or mistrusted, both traditional parties, and support for the Sifton government was temporary, not deeply rooted. Even fiscal policies were “calculated to avoid giving offence to the agrarian interest.”

With the advent of World War I the demands of the UFA only increased. Pressure from the farmers, from other well-organized lobby groups, and from the perceived moral exigencies of war led Sifton to introduce two important, and related, measures: Prohibition and votes for women. A referendum on Prohibition was held in 1915 and was carried by a large majority; the government passed the Liquor Act the next year. Despite the efforts of the UFA and such activists as Emily Gowan Murphy [Ferguson*] and Helen Letitia McClung [Mooney*], Sifton had refused to allow women to vote in the referendum; however, he promised a government measure in 1916 to place “men and women in Alberta on the basis of absolute equality so far as Provincial matters are concerned.” Assented to in April that year, the act made Alberta the third province, after Manitoba and Saskatchewan, to grant women the vote.

Another question that concerned Sifton was the issue of provincial control of natural resources, which for the three prairie provinces remained under federal control. He had raised the matter with Laurier in March 1911, and he forwarded his letter to Robert Laird Borden* shortly after the latter became prime minister that fall. In 1913 at a dominion-provincial conference the premiers of Manitoba and Saskatchewan, Sir Rodmond Palen Roblin* and Thomas Walter Scott*, joined with Sifton in asking for a meeting "to consider the transfer to the prairie provinces of the natural resources within these provinces." Despite the fact that Borden had long ago committed himself to transferring control, federal-provincial discussions were unproductive. Nevertheless, Sifton refused to make a public issue of attacking the federal government. He did not believe in east versus west, he noted in a Montreal interview in 1913. Rather, he was reported as saying, he stood for "a Canada united whether on matters of tariff or imperialism." "'We must pull together,' is his motto."

Such views may at least partially explain Sifton’s actions in 1917. In June his government was sustained in a provincial election, with 34 Liberals elected against 19 Conservatives and 3 Independents. But by that time a crisis was brewing in federal politics over the related issues of conscription of manpower for overseas military service and the formation of a non-partisan government to ensure, among other things, that conscription was carried out. The issue severely divided the Liberal party, both nationally and in Alberta, between the unionists, who believed that wholehearted commitment to winning the war must be paramount, and the Laurier loyalists, who agreed with Sir Wilfrid in his opposition to both measures. Early in August, Sifton attended a Liberal convention in Winnipeg, at which he attacked the Borden administration and its war record; coalition under Borden would be impossible. However, the Borden cabinet baulked at the idea of coalition under another leader, and eventually, in early October, Sifton agreed to enter the new Union government. He retired that month as premier of Alberta and was succeeded by Charles Stewart*. Having been sworn in as dominion minister of customs on 12 October, he was elected for the constituency of Medicine Hat in the federal election of 17 December.

During his time in Ottawa Sifton was probably one of the least known members of the government. His declining health reinforced his tendency to be reclusive and speak little; apparently he never walked any distance, but required a car to transport him even the few hundred yards from his apartment in the Château Laurier hotel to the House of Commons. He was deliberately given what were thought to be light portfolios, serving as minister of customs and inland revenue from 18 May 1918 to 1 Sept. 1919, as minister of public works from 3 September to 30 Dec. 1919, and as secretary of state from 31 Dec. 1919. He also served on the war committee of the cabinet and, in 1919-20, as the first chairman of the Air Board, which was designed to establish standards and structures for regulating air traffic in Canada. In none of these positions did he make a great impact, though he did his work with efficiency. Yet his colleagues valued his concise and articulate contributions in council: as Borden later recalled, “Among his colleagues, his rare intellectual power was universally acknowledged; in questions of difficulty, there was no one in whose judgment I placed firmer reliance, while I was head of the Government.”

Probably Sifton’s greatest contribution came in the behind-the-scenes work he did as a Canadian delegate – along with Borden, C. J. Doherty, and Sir George Eulas Foster* – to the Paris Peace Conference in 1919. He served as vice-chair of the commission on ports, waterways, and railways and represented Canadian interests with respect to the commission on aerial navigation. He also assisted in the preparation of the labour convention, which established the International Labour Organization, and the drafting of regulations governing international flying. His main concern always was to ensure recognition of Canada’s equality of status among the nations. He found to his chagrin that constant vigilance was necessary because his country’s closest allies, the British and the Americans, were frequently inclined to include Canada in a generic category of the British empire, the interests of which were assumed to be one. Asked to contribute his thoughts for a volume commemorating the peace conference, Sifton wrote, “Canada has no desire in return for or in regard to her sacrifices save that in matters in which she is vitally interested she should be treated as an equal.” This position would not be fully acknowledged until the Balfour Declaration of 1926. In the absence of Sir Robert Borden, Sifton and Doherty signed the final form of the peace treaty on 28 June 1919 at Versailles.

Early in 1921 Sifton took leave from his duties for a few days, stating that he required rest and quiet. Unhappily his health became rapidly worse. Then, just when it seemed that there might be hope for improvement, his condition again suddenly deteriorated and he died at home in Ottawa about 8:30 a.m. on 21 Jan. 1921. He was buried there three days later in Beechwood Cemetery. “In him,” observed Borden, “the country loses a public servant of the highest ability and of the most conspicuous patriotism.”

[A portrait of Arthur Lewis Watkins Sifton by Victor Albert Long hangs in the Legislative Building in Edmonton.

A. L. W. Sifton left few personal papers. The largest collection is in LAC, MG 27, II, D19, but this material consists almost entirely of official papers relating to his duties as a cabinet minister or his role at the Paris Peace Conference. The other major collection, in the Legal Arch. Soc. of Alberta (Calgary), comprises Sifton’s judicial notebooks. There are quite a few letters from Sifton to his brother in the Sir Clifford Sifton papers (LAC, MG 27, II, D15), mostly in the period 1896-1903. There are also useful, if scattered, documents in the Laurier, Borden, and Arthur Meighen* papers (LAC, MG 26, G, H, and I).

Sifton’s early life has been pieced together largely from accounts in newspapers and standard biographical sources. Several obituaries also cast light on his career. Of the secondary sources, the most valuable is L. G. Thomas, The Liberal party in Alberta: a history of politics in the province of Alberta, 1905-1921 (Toronto, 1959), which despite its age is the only serious scholarly examination of Sifton’s time as premier of Alberta. The entry in L. [A.] Knafla and Richard Klumpenhouwer, Lords of the western bench: a biographical history of the supreme and district courts of Alberta, 1876-1990 (Calgary, 1997), is most helpful on Sifton’s judicial career. [d.j.h.]

Univ. of Alta Arch. (Edmonton), file 2315-5 (honorary degree recipients). Calgary Herald, November 1898-June 1899 (weekly ed.); 10 Oct. 1914 (daily ed.). Edmonton Journal, 10 Oct. 1914. Manitoba Free Press, 22 Jan. 1921. Montreal Daily Star, 21 Jan. 1921. Morning Albertan (Calgary), 12 Oct. 1914. Ottawa Citizen, 21 Jan. 1921. Ottawa Evening Journal, 21 Jan. 1921. Standard (Montreal), 8 Nov. 1913. Toronto Daily Star, 21 Jan. 1921. Alberta in the 20th century: a journalistic history of the province, [ed. Ted Byfield et al.] (12v., Edmonton, 1991-2003), 2-3. D. R. Babcock, Alexander Cameron Rutherford: a gentleman of Strathcona (Calgary, 1989). Canadian annual rev., 1901-21. Canadian directory of parl. (Johnson). Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1912). CPG, 1899-1920. Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose and Charlesworth), vol.3. J. W. Dafoe, Clifford Sifton in relation to his times (Toronto, 1931). Directory of the Council and Legislative Assembly of the North-West Territories, 1876-1905 (Regina, 1970). D. J. Hall, Clifford Sifton (2v., Vancouver and London, 1981-85); “T. O. Davis and federal politics in Saskatchewan,” Saskatchewan Hist. (Saskatoon), 30 (1977): 56-62. J. S. Heard, “The Alberta and Great Waterways Railway dispute, 1909-1913” (ma thesis, Univ. of Alta, 1990). C. C. Lingard, Territorial government in Canada: the autonomy question in the old North-West Territories (Toronto, 1946). The official history of the Royal Canadian Air Force (3v. to date, [Toronto and Ottawa], 1980- ), vol.2 (W. A. B. Douglas, The creation of a national air force, 1986). Faye Reineberg Holt, “Women’s suffrage in Alberta,” Alberta Hist. (Calgary), 39 (1991), no.4: 25-31. C. B. Sissons, A history of Victoria University (Toronto, 1952). Standard dict. of Canadian biog. (Roberts and Tunnell), vol.1. L. H. Thomas, The struggle for responsible government in the North-West Territories, 1870-97 (Toronto, 1956). Paul Voisey, “The ‘votes for women’ movement,” Alberta Hist., 23 (1975), no.3: 10-23.

Cite This Article

David J. Hall, “SIFTON, ARTHUR LEWIS WATKINS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/sifton_arthur_lewis_watkins_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/sifton_arthur_lewis_watkins_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | David J. Hall |

| Title of Article: | SIFTON, ARTHUR LEWIS WATKINS |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | March 1, 2026 |