Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

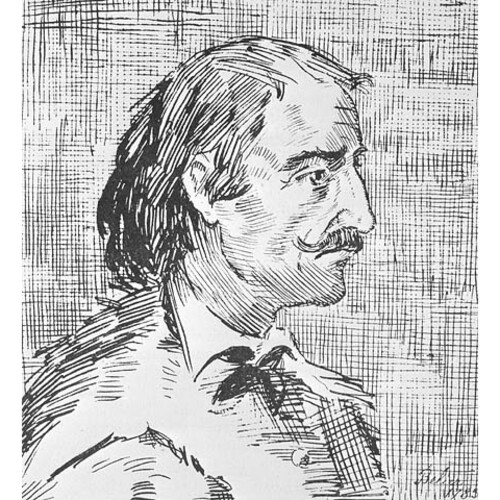

RADISSON, PIERRE-ESPRIT, explorer, coureur de bois, one of the originators of the Hudson’s Bay Company; b. c. 1640, in Avignon (?), France; d. 1710 in England.

Little is known of the explorer’s parents, birth, and early childhood. In an affidavit dated 1697 and a petition of 1698, Radisson himself states that he was then 61 and 62 years of age respectively, thereby indicating that he was born in 1636. A 1681 census of New France, however, lists him as 41 years of age. There is considerable evidence that the Radisson family came from the lower Rhone area, in or near Avignon. A Pierre-Esprit Radisson, presumably the explorer’s father, was baptized 21 April 1590 (N.S.) in Carpentras, and in 1607 was living in Avignon; the senior Radisson married Madeleine Hénaut, widow of Sébastien Hayet.

Marguerite Hayet, a daughter of Madeleine Hénaut’s first marriage, was to play quite an important part in the young Radisson’s life. Presumably the boy came to New France with his half sister, or as a result of her being in that new country. It is known that Marguerite was in Quebec in 1646 for at that time she married Jean Véron de Grandmesnil. This was a time of difficulty, danger, and tension in New France; the fur trade was being constantly interrupted by Iroquois raiding parties, and life was hazardous even within the confines of the settlements. It was during one of the Indian raids that Marguerite’s husband was killed; in August 1653 she married again, this time Médard Chouart* Des Groseilliers, the man who became Radisson’s partner in the exploration of North America.

Nothing is known, however, of Radisson’s arrival in New France. The first mention we have of his presence there is his capture by Iroquois Indians, possibly in 1651. Like his half-sister he was at that time living in Trois-Rivières.

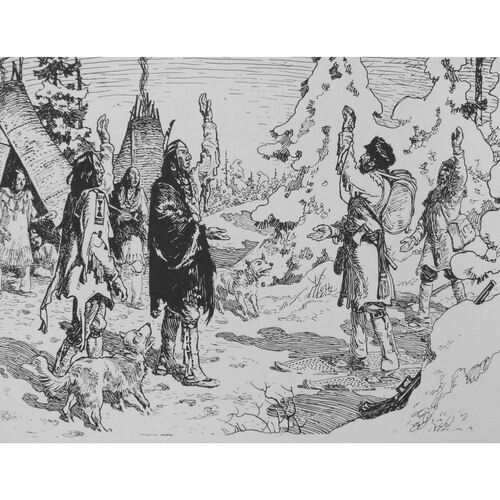

According to Radisson’s account, he was taken by his captors to a Mohawk village near present-day Schenectady, N.Y. Presumably because of his youth, he was treated kindly and adopted by an Indian family of prominence. He learned the local language readily and went on expeditions with the natives, adapting himself with remarkable facility to his new environment. Eventually, however, in somewhat treacherous circumstances, he effected his escape and almost succeeded in getting back to Trois-Rivières. Recaptured and brutally tortured, he was saved from death through the intervention of his Iroquois “family,” and given an Indian name, Oninga. The following spring he went on a hunting trip with his Indian friends and later described the adventure, which included an encounter with an alligator-like reptile: “there layd on one of the trees a snake wth foure feete, her head very bigg, like a Turtle, the nose very small att the end.” A little later (1653) Radisson went on another trip with his Indian friends, this time to Fort Orange, the Dutch outpost on the site of present-day Albany, N.Y. The governor there offered to ransom Radisson, but the latter refused and returned to his Indian village. He then repented his decision, escaped, and reached Fort Orange safely. He was serving there as an interpreter for the Dutch when the Jesuit priest, Joseph-Antoine Poncet*, arrived. Radisson was shipped back to Europe, arriving in Amsterdam in the early weeks of 1654. Later the same year he returned to Trois-Rivières; his brother-in-law had probably already left on a two-year venture into the interior of the continent.

Des Groseilliers’ trip is recorded in the Jesuit Relations, which state that there were two men in the party. It was assumed for many years that Radisson was the other man; in his own reminiscences he claims to have been his brother-in-law’s companion. However the discovery of a Quebec deed of sale dated 7 Nov. 1655, and bearing Radisson’s signature, makes it obvious that he could not have taken part in this expedition.

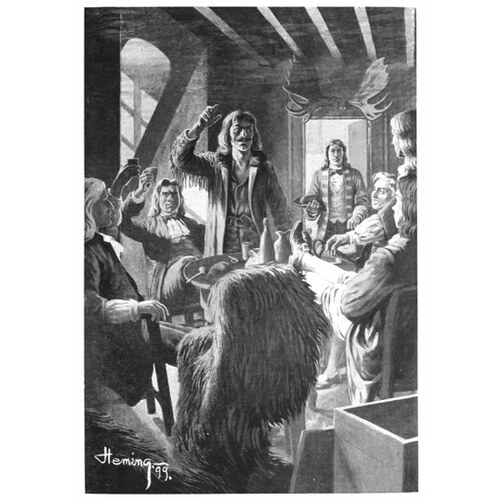

During Radisson’s absence, in 1654, peace had been made “betweene the french and ye Iroquoits.” In 1657 he accompanied a Jesuit missionary party, which included Father Paul Ragueneau*, to Sainte-Marie-de-Gannentaa (Onondaga), established in 1656 by Joseph-Marie Chaumonot* and Claude Dablon*, in Iroquois country, not far from the site of Syracuse, N.Y. Radisson has left a colourful account of this episode, which tells of growing Indian disaffection with the venture. Finally the Iroquois determined to get rid of the unwelcome intruders. Learning of this plan, the Frenchmen made ready to depart as soon as possible in the spring of 1658 but they realized that great caution must be used to prevent the Iroquois from discovering their intentions. Radisson’s familiarity with Indian psychology and Indian language proved adequate for the task. We have several contemporary accounts of the episode, suggesting the curious stratagems used by the French to deceive the natives. Marie de l’Incarnation [Guyart*] writes: “A young Frenchman, who had been adopted by a renowned Iroquois and who had learned their language, told his [Indian] father that he had had a dream that he must provide a feast, where everything must be eaten or he should die.” Obedient to the dream message, all the Indians came to the feast, and religiously consumed the vast quantities of possibly drugged food and drink. The din of music and merriment ensured that the drowsy Indians did not hear any noise as the French prepared to escape. Father Paul Ragueneau, then in charge of the mission, adds: “He who presided at the ceremony played his part with such skill and success that each one was bent on contributing to the public joy.” Charlevoix*’s account mentions that it was a young man playing on a guitar who lulled the natives to sleep and thus allowed the French to escape unharmed. It is possible, even probable, that the young hero was Radisson.

Radisson’s next adventure was a trip with Des Groseilliers to the far end of Lake Superior and the unexplored wilderness south and west of that great inland sea. They set out in August 1659 and returned to Montreal on 20 Aug. 1660. Of this journey Radisson has left us an account that is exact and convincing, with enthusiastic descriptions of the countryside and detailed reports of their strange, varied, and often harrowing experiences.

Governor Argenson [Voyer] insisted that one of his men accompany Des Groseilliers and Radisson, but the two explorers managed to slip away from Trois-Rivières unnoticed. They reached Lake Superior and from there they pressed inland and spent the winter with Huron and Ottawa refugees on a smaller lake, probably Lac Courte-Oreille or Ottawa Lake. Close at hand were Sioux, the resident Indians of the area with whom the two Frenchmen became acquainted, possibly the first white men to do so. It was a hard winter with heavy snowfalls; many Indians died of starvation. Radisson tells how the Indians, unable to see Des Groseilliers’ emaciated face beneath his beard, concluded that he was being fed by some Manitou, but, “for me that had no beard, they said I loved them, because I lived as well as they.”

Radisson’s narrative contains a most valuable account of Indian customs – including a vivid description of the great Feast of the Dead, which took place in the winter of 1659–60, and to which “eighten severall nations” came. It was at this time that the explorers probably gained much of their knowledge of the geography of the country between their camp and Hudson Bay and of the “great store of beaver” there and to the west, which some years later became the basis of their argument for convincing Englishmen to establish the Hudson’s Bay Company. After the feasting ended the two men journeyed into Sioux country where they remained six weeks. Returning to Lake Superior in the spring, they crossed to its north shore, and there visited the Cree. At this point in Radisson’s narrative comes another apocryphal journey, this time to Hudson Bay. Such a trip could not have been accomplished in the time at their disposal, but later when he was writing his account Radisson was anxious to appear as knowledgeable as possible about the fur trade and exploration of North America.

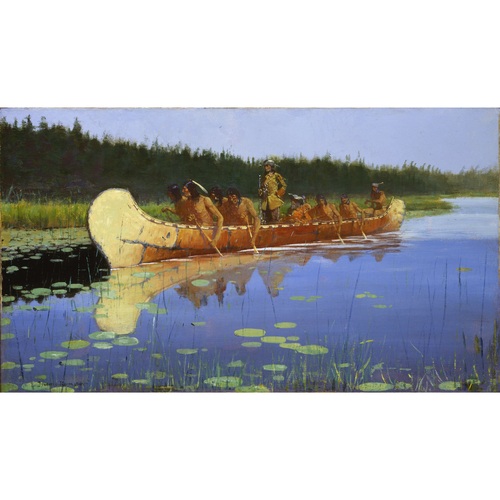

The following summer, 1660, the two Frenchmen and a great company of Indians left Lake Superior for Montreal. There Des Groseilliers made a business arrangement with Charles Le Moyne*, the contract for which is dated 22 Aug. 1660; the Jesuit record for that year states that the company of Indians, 300 in number, reached Trois-Rivières on 24 August. Marie de l’Incarnation also tells of the arrival of the flotilla of canoes with their “heavenly manna” of beaver skins and reflects that this would save the colony of New France from economic ruin.

Disappointment was in store for the triumphant explorers. Radisson tells of the hard usage he and his brother-in-law suffered when greedy officials confiscated a large part of the furs, threw the older man into jail, and fined both men – presumably for having gone to the west without the governor’s permission. Thereupon Des Groseilliers betook himself to France, hoping to get justice, but being disappointed returned to New France. Preparations were made for another wilderness expedition and in the spring of 1662 Radisson and Des Groseilliers embarked, so they announced, for Hudson Bay. Either by pre-arrangement or by force of circumstances, however, they abandoned the trip to the north and sailed instead to New England. There they were received more affably than they had been by their compatriots, and during the next two or three years they made at least two unsuccessful attempts to get to Hudson Bay by ship. In July 1664 the commissioners of the king of England arrived in Boston on empire business. Radisson and Des Groseilliers were interviewed and persuaded to go to London; they left New England on 1 Aug. 1665 (o.s.) in the Charles (Capt. Benjamin Gillam).

The war between England and the Dutch states for the supremacy of the sea was raging fiercely at this time. It has been suggested (Marie de l’Incarnation and Ragueneau) that the conquest of New Holland by the New Englanders was inspired by Des Groseilliers who relied no doubt on Radisson’s knowledge of the Iroquois country and its fur trading possibilities. In any case, on leaving New England, the two explorers were caught up in the Anglo-Dutch hostilities. The Charles was captured by a Dutch vessel and looted; her papers were thrown overboard and her passengers and crew landed in Spain. Radisson and Des Groseilliers quickly made their way to London, where they were well received – the cost of their maintenance being paid by the king. The two explorers soon found that life in Stuart England could be as hazardous, violent, and colourful as in the untamed Iroquois country – they were witness to the Great Plague and the, devastating fire of London, the gay court functions in Charles II’s Oxford.

Until this point in Radisson’s life we have had to rely almost exclusively on his own account – a fascinating but often dubious source – but from this point on his version can be supplemented from official documents in the archives of the HBC, which take up the story of the search for the northwest passage via Hudson Bay and of attempts to gain control of the beaver country of northern North America.

In 1668 after various set-backs the men who were to found the HBC sent out two vessels, the Eaglet with Radisson aboard and the Nonsuch carrying Des Groseilliers. Radisson’s vessel was damaged in a storm and had to limp back to England, where the explorer spent the ensuing winter writing his Voyages at the king’s express command. After completing his narrative Radisson fruitlessly attempted again to reach Hudson Bay. Meanwhile the New England captain of the Nonsuch, Zachariah Gillam* (brother of Capt. Gillam of the Charles and probably already experienced in arctic seamanship) had been successful in his search for a way into Hudson Bay. In early October 1669 Des Groseilliers returned from the bay with a fine cargo of beaver skins, and a fresh incentive was given to the scheme for establishing the HBC. Its charter passed the great seal on 2 May 1670, and almost immediately, 31 May 1670, the two Frenchmen started once more for Hudson Bay.

The vessel on which Radisson was travelling, the Wivenhoe (Capt. Robert Newland), made for the mouth of the Nelson River, where possession for England was formally taken by that enigmatic figure, Charles Bayly*. Des Groseilliers, aboard the Prince Rupert (Capt. Zachariah Gillam) with Thomas Gorst* as a passenger, returned to his post of the preceding year at the mouth of Rupert River. There Radisson joined him shortly after difficulties had arisen in the new western colony, including the death of Capt. Newland and damages to the ship. However, the abortive expedition was not without consequences for the future. Radisson’s knowledge of the place, gained from this first visit, and his insight into the vital importance for the fur trade of a base at Port Nelson, were to prove useful in 1682, when Radisson attempted to found a French colony in that location. On the other hand, this brief sojourn at Port Nelson and the formal act of possession by Bayly were subsequently to constitute England’s main claim to much of central North America.

Journeying back and forth between England and Hudson Bay and advising their employers about provisions and trading commodities kept Radisson and his brother-in-law occupied until 1675. During these years there was growing apprehension in New France about the activities of the two explorers and of the HBC; the intendant, Talon*, urged an expansionist policy to counterbalance English encroachments. He sent expeditions west under Cavelier* de La Salle and Daumont* de Saint-Lusson. A further party under Paul Denys de Saint-Simon and the Jesuit Father Albanel* penetrated into HBC territory. In 1675, however, Albanel, by that time a prisoner in England, persuaded Radisson and Des Groseilliers to return to French allegiance.

So the two explorers slipped quietly across the channel once more followed by a volley of disparaging representations to the French court from the English government. They had been promised favourable treatment by the Jesuits, but they did not receive it from the French court and were sent back to Canada by Colbert to consult with Frontenac [Buade*]. The governor was suspicious of them and their Jesuit promoters, however, fearing that any favours to them would react unfavourably for his own protégé, La Salle. It was immediately obvious that nothing was to be looked for in that quarter: Des Groseilliers returned to his Trois-Rivières home and Radisson sailed for France.

Radisson now found himself without occupation in France in a period of great unemployment. He sought assistance from a powerful figure in the shadows of the French court, Abbé Claude Bernou, La Salle’s attorney. The result was a place as a midshipman in an expedition of Vice-Admiral d’Estrées to capture the Dutch colonies along the coast of Africa and in the Caribbean (1677–78). For this chapter in Radisson’s career we have the only known letter of any length wholly written and signed by him. After initial success, the campaign ended disastrously on hidden reefs in the Caribbean. Most of the vessels were wrecked and Radisson barely escaped with his life, after losing all his possessions. Returning to France, he petitioned for relief and received a sum of money but not the position in the navy that he says he had been promised.

Colbert had previously intimated to Radisson that one reason for his having received so little help in France was the fact that he had not brought his wife with him from England. Sometime between 1665 and 1675 – probably in 1672 – he had married the daughter of Sir John Kirke of the HBC, who had inherited from his father, Gervase Kirke, claim to a considerable part of the northeastern region of North America. We know little about this woman, not even her first name, but we do know that she was not the notorious courtesan of the day, Mary Kirke, with whom she has often been confused. Disgruntled after the Caribbean fiasco, Radisson returned to England on the pretext of attempting once more to bring his wife to France. But Kirke would not allow his daughter to leave the country. Radisson then put out feelers to learn what he could hope for should he return to the HBC’s service, but the results were not encouraging.

In Paris, however, a new avenue was opening for him. In 1681 Radisson was approached by the Canadian merchant, Charles Aubert de La Chesnaye, who, in the following year, was granted a fur-trading charter by Colbert (Compagnie du Nord). (The minister could not openly support the scheme because of the temporarily harmonious relationship between the English and French crowns.) The unofficial nature of this transaction, however, increased the confusion when the expedition arrived in Canada – Frontenac refusing to grant permits to La Chesnaye and Radisson.

Eventually the expedition got under way, its ultimate object being the founding of a French colony at the mouth of the Nelson River. May we assume that Radisson had learned on his recent visits to London of the HBC’s intention of again founding a colony on that disputed spot? The Port Nelson contest was not, however, to be a simple French/English struggle. Interlopers from New England led by Benjamin Gillam (a nephew of the captain of the Charles) also turned up in the bay in the late summer of 1682. Claims and counterclaims were soon made that this party or that one had reached the mouth of the river first and taken possession. Radisson and Des Groseilliers (who had joined him) were able by subterfuge and force, as well as by better knowledge of the countryside and its wild inhabitants, to get possession of the area, capturing among others John Bridgar*, the governor of the new English colony, and acquiring many furs for France.

Flushed with success they returned to Quebec, where an attempt to avoid paying tax on their furs resulted in their being sent by Le Febvre* de La Barre to France for “adjudication of the case.” There they expected great reward from Colbert. To their consternation they learned on landing that the minister was dead, and that heed was being paid in France to the complaints of the outraged HBC. Whatever their prestige in New France, Radisson and Des Groseilliers were only small pawns in the politico-religious intrigues of late seventeenth-century Europe. Des Groseilliers soon found himself back in Canada, and within a year (1684) Radisson was again in the employ of the HBC.

Radisson’s return to England was brought about by a French Protestant, a former lawyer at the parlement of Paris, named Gédéon Godet, an employee of Lord Preston, the English envoy extraordinary at the court of Louis XIV. Godet, a colourful but suspect character, was anxious to get out of France, where he was being persecuted for his religion; he plotted to do so by means of Radisson’s defection to the English, hoping at the same time to engineer his own advancement and his daughter’s marriage. Both men escaped across the Channel. Radisson was greeted rather warily by the company, which sent him immediately back to Hudson Bay, “where he hath undertaken without hostility to reduce the French . . . and to render us the quiet possessions of yt place. . . .” There, with remarkable aplomb, he prevailed upon his nephew, Jean-Baptiste Des Groseilliers, in charge of the post at the mouth of the Nelson – which Radisson had helped to secure for the French – to go over to the English side, with all his men and a great cargo of furs. As they slipped out of the bay on their way back to England, Radisson’s party only just escaped detection by French ships coming to relieve young Des Groseilliers.

The two Frenchmen went to London to a cold winter and the coronation of James II, erstwhile governor of the HBC. Subsequently Des Groseilliers’ son tried several times to escape back to the French side, but his attempts were thwarted. In 1685, Denonville [Brisay] offered a reward of 50 pistoles to anyone bringing Radisson to Quebec; and in 1687 Seignelay wrote urging Denonville and Bochart de Champigny to ensure Radisson’s return to the French cause – either by persuasion or by force. But the versatile explorer was destined to spend the rest of his working years in the service of the HBC.

From 1685 to 1687 Radisson was resident in Hudson Bay – his last trip to Canada. During this period he was given considerable authority in all trading matters by the company, yet before his return in 1687 many disputes had arisen between him and the other officials of the HBC.

On 3 March 1685 Radisson had married Margaret Charlotte Godet, daughter of Gédéon, in the church of St Martin’s in the Fields, London. Presumably his first wife, the mother of one child, had died. Now, in 1687, Radisson returned to England to live the rest of his life as a family man in the quiet of London suburbs.

On his return to the company in 1684, he had been granted company stock, and later an annuity of £100 sterling a year. Some of this promised financial support having been withdrawn in the early 1690s, he went to court against the company and won his suit in chancery in 1697 after years of litigation, thus demonstrating once more his tenacity, audacity, and astuteness. Thereafter the company was faithful in its payments to him. In 1687 Radisson and his nephew were naturalized at the company’s expense.

His life between 1700 and his death in the early summer of 1710 is a relative blank. The company’s only references to him relate to the payment of his annuity and the dividends on his stocks. Some time between 1692 and 1710 – probably at the delivery of a fifth child – Margaret Radisson died, and Pierre married for the third time. This wife’s name was Elizabeth and she bore him three daughters, who are described in his will as “small.” She survived him for many years, died in extreme poverty, and was buried, it would appear from extant records of interment, in London on 2 Jan. 1732.

On 17 June 1710 Radisson made his will, which is preserved in Somerset House, London. In it he tells not a little of his life. His wife Elizabeth is mentioned and also his “former Wifes Children,” who were “by me according to my ability advanced and preferred to severall Trades.” Sometime between 17 June and 2 July 1710 the old explorer died and his will was probated. The company paid his widow six pounds, presumably for funeral expenses. The exact date of his death and the place of interment are not known.

Radisson seems to have been one of those fortunate people endowed with an unquenchable zest for life and a capacity for adaptation not too greatly hampered by religious, moral, or patriotic scruples. He stands for all that is rich and colourful in an age of adventure and intrigue, brutality and imagination. As an explorer he had not only the ability to endure the mental and physical hardships of life in the wilderness, but also an instinctive insight into the potentialities of certain trading areas and routes. His uncanny appreciation of Indian psychology and his spontaneous enthusiasm for natural beauty enabled him to describe the lands he discovered, and to chronicle the life of the inhabitants. A simple coureur de bois, who had lived, hunted, and killed with the Indians, he was involved in matters of international importance, moved in court circles, and conversed with kings. Sometime French and Catholic, sometime English and (probably) Protestant, he witnessed the plague and the fire of London, the coronation of James II, the founding of the HBC. He wintered in the frozen north and went campaigning in the Caribbean. Though Radisson was an opportunist and a disturbing and unreliable character, we cannot but admire his versatility and his exuberance.

The original French manuscript of the account of his travels which Radisson wrote in the winter of 1668–69 has been lost. However an English translation must already have been completed in 1669, for in June of that year the unknown translator – possibly Nicholas Hayward, later the HBC’s French translator – was paid £5 for his work. This translation has been preserved in the papers of Samuel Pepys in the Bodleian Library at Oxford, England. When Radisson wrote these reminiscences he was anxious to bolster the confidence of the men who were to found the HBC, and so he edited his account rather shamelessly, inserting the fictitious journey to Hudson Bay in 1659–60 and implying that he had been Des Groseilliers’ companion in 1655. Radisson’s writing is remarkably vivid and precise, except in the “edited” sections, where his vague, ambiguous style betrays him immediately. A transcription of the Voyages and of other of Radisson’s writings appeared in 1885: [Pierre-Esprit Radisson], Voyages of Peter Esprit Radisson, being an account of his travels and experiences among the North American Indians, from 1652 to 1684, transcribed from original manuscripts in the Bodleian Library and the British Museum, ed. G. D. Skull (Prince Soc., XVI, Boston, 1885; New York, 1943). For details of the many other manuscript sources used, from collections in France, England, Canada and the U.S.A., see Nute, Caesars of the wilderness, 359–63. [g.l.n.]

Charlevoix, Histoire. Marie Guyart de l’Incarnation, Lettres (Richaudeau). HBRS, V, VIII, IX (Rich); XI, XX (Rich and Johnson); XXI, XXII (Rich). JR (Thwaites). See also Phil Day, “The Nonsuch ketch,” Beaver (Winnipeg), outfit 299 (Winter 1968), 4–17.

Cite This Article

Grace Lee Nute, “RADISSON, PIERRE-ESPRIT,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 2, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/radisson_pierre_esprit_2E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/radisson_pierre_esprit_2E.html |

| Author of Article: | Grace Lee Nute |

| Title of Article: | RADISSON, PIERRE-ESPRIT |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 2 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1969 |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | January 26, 2026 |