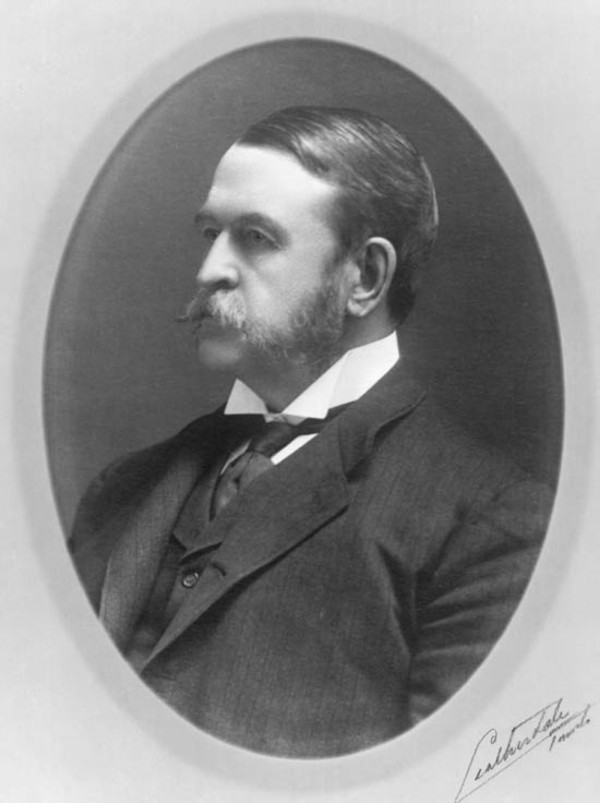

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

WHITNEY, Sir JAMES PLINY, lawyer and politician; b. 2 Oct. 1842 in Williamsburgh Township, Upper Canada, son of Richard Leet Whitney and Clarissa Jane Fairman; m. 30 April 1877 Alice Park (d. 1922) in Cornwall, Ont., and they had a son and two daughters; d. 25 Sept. 1914 in Toronto and was buried near Morrisburg, Ont.

The son of a blacksmith-farmer, J. P Whitney secured his early learning in a rural setting. By 1860 he had advanced to the Cornwall Grammar School and membership in the local volunteer militia. Upon completing his education, he entered the law office in Cornwall of John Sandfield Macdonald* and John Ban Maclennan. Although as a prominent politician Macdonald had more important matters before him than the legal training of young Whitney, he made time for him. Whitney later credited the older man with tutoring him in politics as well as in law. He viewed Sandfield as a Baldwin Liberal who, after Robert Baldwin*’s retirement, had moved away from the Reform party and into the Liberal-Conservative camp of John A. Macdonald*. When, as a Conservative, Whitney assumed the premiership of Ontario, he saw himself, philosophically, as a descendant of Sandfield, announcing with pride that he came “from Liberal (Baldwin) stock.”

Whitney’s pursuit of a legal career did not follow a straight path. In the late 1860s he disappeared from Cornwall. He surfaced occasionally at his father’s farm near Aultsville, and unsubstantiated stories suggest that alcohol may have been at the root of his wanderings. If his whereabouts remain a mystery, his politics do not because, when he can be sighted, it is as a labourer for the Liberal-Conservatives. He resumed his legal studies about 1871. Called to the bar at the age of 33, in Easter term 1876, he set up practice in Morrisburg in May. In this village of some 1,600, located near one of the St Lawrence canals and astride the Grand Trunk Railway, Whitney soon acquired a reputation as a dogged practitioner. Thus established, he thought his future sufficiently secure that he could marry Alice Park of Cornwall in 1877. If Whitney brought bright economic prospects to the relationship, Alice brought the firm hand that reined in his drinking.

Although a household and a professional career were foremost in Whitney’s mind in the late 1870s, politics nudged them for prime space. After a decade of serving the Conservative cause as a back-room man, he stepped forward for Dundas, a Tory riding since 1875, when Liberal premier Oliver Mowat* called a provincial election for December 1886. This candidacy placed Whitney under the leadership of William Ralph Meredith*, the party’s provincial chieftain, and into a noisy campaign where religious and educational issues dominated debate. This situation stemmed from the charge that Mowat was subservient to Roman Catholics in matters of education and that, consequently, they supported him at the polls. Although Meredith tried to evade this treacherous bog, the language of the ultra-Conservative Toronto Daily Mail [see Christopher William Bunting*] drew him into it, with the result that he was labelled anti-Catholic. In Dundas, however, Whitney’s lack of the folksy touch, not religious questions, was most likely the chief reason for his narrow loss to Theodore F. Chamberlain*. The Tories contested this result on the grounds of bribery and corruption, paving the way for a by-election in January 1888. Unencumbered by the nasty religious aspects of the general election, Whitney played the theme of honesty versus corruption for the first but certainly not the last time in his long political career. He recaptured Dundas for the Conservatives by 28 votes and he found himself at Meredith’s side in the legislature. The Tory leader would prove to be the dominant personal influence in the shaping of a country lawyer into a provincial premier.

To Whitney, Meredith’s intelligence may have seemed the only positive aspect of joining the opposition ranks. The Conservatives lacked men, money, and organization, and they were sapped by religious controversy, frustrated by electoral failure, and handicapped by the position of the federal Tories on provincial rights. Matters did not improve in the provincial election of 1890. Although Whitney secured re-election, the Liberals were returned to power in a campaign which was marked once more by Conservative cries of Liberal subservience to the pressures of Catholicism, particularly in the matter of separate schools. This criticism, no matter how carefully phrased by Meredith, simply drove Conservative Catholics into the arms of Mowat.

Whitney subsequently rose steadily in the ranks of the Tory legislators. He became the Conservative critic and chief spokesman on education, judicial administration, and electoral corruption. But in the early 1890s larger forces were starting to reshape Ontario’s political landscape: a slow economy, a federal government seemingly made irresolute by Macdonald’s death in 1891, acrimonious wrangling between Catholics and Protestants and between French- and English-speaking Canadians, the resentment of farmers at the protective tariff, the conviction that alcohol lay at the base of a growing list of social ills, and the discontent of Ontario’s lower classes. Two new political parties arose to give form to this malaise: a farmers’ protest movement, the Patrons of Industry, and an anti-Catholic organization, the Protestant Protective Association [see George Weston Wrigley*; D’Alton McCarthy*]. Whitney denounced the appearance of groups that would upset the two-party system. Although conscious of the political harm that Protestant extremism could produce, he saved his harshest words for the Patrons. In his opinion there was no place for the conversion of a potentially useful farmers’ organization into a political party. Faced only by a Patron opponent, he was re-elected in June 1894.

Another opportunity for Whitney’s political elevation occurred when, after his fifth straight defeat at the hands of Mowat, Meredith accepted an appointment in October as chief justice of the Court of Common Pleas. Whitney flirted with the idea of seeking the Conservative leadership but he knew that the new leader would have to attempt working with the Patrons to discomfort Mowat and decided he was not the man for the task. The leadership went to George Frederick Marter*, who managed to commit the party to prohibition and the abolition of separate schools, only to reverse direction when protests against these policies proved deafening. This shift, which caused Whitney much irritation, nevertheless served the Conservatives well in the long run because the party was now able to distance itself, slowly, from its longstanding reputation for hostility to Catholicism and separate schools.

Although Whitney continued to be annoyed with his leader, likely because Marter’s action prevented him from taking up issues such as authorized texts and the certification of teachers for separate schools, he did not permit his feelings to get in the way of work in the legislature. There he led the party away from becoming embroiled in the Manitoba school issue in 1896 [see Thomas Greenway*] by arguing that such a matter was beyond the competence of the Ontario body. His ability to control most of the caucus in this instance may have been a factor in its decision to make him leader when Marter stepped aside in April 1896. Whitney now had the task of breathing fresh life into a Tory organization which seemed fated to be the perpetual opposition.

Whitney’s first chore was to do battle in the federal election campaign of 1896, which would have a marked effect on the fortunes of the provincial Tories. He argued across the breadth of southern Ontario for the use of federal remedial legislation to resolve the problem of denominational schools in Manitoba. Such action meant that Whitney and his provincial followers were moving still further away from the charge that they were anti-Catholic. The election had another, more important consequence for Ontario Tories. The departure from the provincial scene of the unbeatable Mowat, who was persuaded to join the Liberal government of Wilfrid Laurier, considerably brightened the prospects of Whitney and his party.

Whitney’s job of rebuilding his party involved the development of a better organization, a safe distancing from the federal Tories to avoid charges of being dominated by them, the extension of a friendly hand to alienated Catholic Conservatives, visits to hostile Grit territory in southwestern Ontario, and hastening the decline of the sagging Patrons. Although Whitney could afford to congratulate himself on the advances he made on all of these fronts in 1896–97, sufficient funds to aid him and the party in their quest for power were not forthcoming. At the same time the income from his Morrisburg law practice had shrunk because of his political activities. His efforts to lead his party were not without a real price, but the costs had to be paid if the Conservatives were to be ready for the next provincial election, which the new Liberal premier, Arthur Sturgis Hardy*, called for March 1898.

In this campaign Whitney moved to strengthen the provincial body by reaching out to Catholics. He was involved in the nomination meeting in Toronto South where James Joseph Foy, a prominent Catholic lawyer and member of the finance committee of the Liberal-Conservative Union of Ontario, was chosen as the party’s flag-bearer. Whitney now had someone in camp who could bear witness to the fact that the old days of anti-Catholicism, imagined or real, were gone. He furthered this impression by saying absolutely nothing about separate schools. The result was a duller but much shrewder Tory campaign. Foy was elected and the Patrons disappeared from sight, but the Liberals narrowly held on to power. The Tory chief, however, could take some comfort from the fact that he now possessed a Catholic right-hand man, and was closing with the Grits.

In the months that followed, Whitney busied himself with election protests in the vain hope of turning out the Liberals by that route and with assailing them on the subject of political purity. In pursuing this course he generated publicity but he also began to acquire a reputation as a politician who warbled about corruption but could sing about little else. None the less, he enjoyed the solid backing of his caucus. The accession as premier in 1899 of George William Ross, the long-time minister of education, should have given Whitney cause for concern – apparently it did not – because Ross was a more vigorous leader than Hardy and he certainly commanded the loyalty of his followers.

Whitney did move to meet criticism which suggested that he had little to put forward as constructive policy. Undoubtedly influenced by Meredith, who in 1900 had become chancellor of the financially troubled University of Toronto, he put forward a concrete plan for that institution in 1901 which would place it on a sound footing by providing funding out of provincial succession duties. He also insisted that there be no government meddling in the areas of university policy and appointments. In the same year he made his first consequential pronouncement on the development of hydroelectricity at Niagara Falls, an issue which Whitney would skilfully build into a progressive crusade with mass appeal. He argued that power developed on the Ontario side should be produced by and for Canadians and expressed a wariness of monopolistic control of a resource that properly belonged to the people of the province.

While Whitney articulated Tory policies, he was beset by troubles that culminated in a run at his leadership in 1901. Aided by Foy and others, he came out of this challenge in firm control, not only of the party, but also of its new organization, the Ontario Liberal-Conservative Association, formed in January 1901. Along the way he had as well to deal with attempts to draw Foy to federal politics, placate an ever more erratic Marter, resist efforts to move him and his Morrisburg household to a permanent Toronto address, watch his law practice fall to almost nothing, and feel the embarrassment of virtually begging for money with which to carry on as party leader. These matters took their toll on his health and temperament, and for a time Whitney, who was normally blunt and aloof, became quite irascible. Once he had hold of the party, however, his spirits lifted because he could again look forward with optimism to battling the Liberals in the next election. The Ontario Liberal-Conservative Association began to pay dividends in the form of useful analyses of the condition of the party at the constituency level. Funds from his capitalist brother Edwin Canfield Whitney eased him over some financially rough spots; then money began to trickle into the party’s coffers, sufficient to quench debts and float a speaking tour of the province by Whitney in the fall of 1901. Not being awash in contributions did afford him an advantage he may not have always appreciated: he was not in anyone’s debt and in that fact lay a degree of freedom.

During the legislative session of 1902 the Tories clearly articulated a policy on hydroelectricity, a matter which had attracted increasing public interest because Ontario was blessed with tremendous potential at Niagara Falls and the problem of long-distance transmission had been solved by the use of alternating current. In addition, Ontario, Toronto and Hamilton in particular, was becoming increasingly industrialized, but the province was coal-poor. Consequently, hydroelectricity held out the hope of cheap and available power, and the prospect dazzled the industrialist, the railwayman, and the public [see John Patterson]. On the Ontario side of the falls, two American-owned power companies had signed contracts in 1902 with the Queen Victoria Niagara Falls Parks Commission, and a Canadian organization was being put together by William Mackenzie*, Henry Mill Pellatt*, and Frederic Nicholls* to consummate a deal for the production of power. Taking all these factors into account, the Conservatives argued in the legislature that, in future agreements, the parks commission must reserve the right for the province to stop the transmission of power beyond Canadian boundaries and that, as existing contracts allowed, water-power should be developed by the government in order to produce electricity as cheaply as possible for sale to municipalities at cost. Although this argument, when shaped into a motion, was lost on a straight party vote on 5 February, it clearly launched the Tories down the path of public power. And Whitney, despite suggestions that he was a reluctant convert to the position, gave voice to this policy at every opportunity.

The session of 1902 was the springboard into a May election, in which Whitney, after damning the Grits to the point of almost obscuring his own policies, ran a confident campaign, one completely lacking in religious overtones. In one speech he concluded his condemnation of Liberal electoral misdeeds with a ringing proclamation that, for many, epitomized the Morrisburg lawyer: “We are bold enough to be honest, we are honest enough to be bold.” Whitney’s control of the party and issues, however, was not enough. The Conservatives garnered more votes than the Liberals, but not more seats; the count was 50 to 48. Although the Tories won control of the major urban centres, the rural regions gave Ross his victory. This narrow defeat did not mark an end to Whitney’s troubles. Contested election results resulted in a number of Liberal triumphs. Then, in March 1903, Robert Roswell Gamey, the Tory member for Manitoulin, publicly threw his support to the Ross government. But, when the legislature opened, Gamey announced that he had been bought by the Grits for $2,000. A commission struck by Ross cleared the Liberals and discredited Gamey but Whitney would have none of it. The episode provided him with fresh ammunition to fire when he recited Grit transgressions, a tactic which had been wearing thin until the Gamey story broke. Ross was sufficiently troubled by its impact on his party that he unsuccessfully approached Whitney with the offer of a coalition government. The Gamey affair was not the end of the Liberals’ woes, because testimony in one contested election, in Sault Ste Marie in 1903, revealed the Grits’ wholesale use of impersonators, whisky, and money and led to a trial the following year.

To revitalize and cleanse his party Ross shuffled his cabinet and called a Liberal convention for late in 1904. He then set an election for 25 Jan. 1905. Whitney, smelling success, was more than ready and, with a united party behind him, he charged into the battle with the renewed cry of Grit Corruption. The result was a 40-seat majority for the Tories, a landslide which slightly staggered even the Conservative chieftain. Ross argued that he had lost largely because of the temperance question and that he had blunted the opposition’s accusations of corruption. Such an explanation puts insufficient weight on the issue of corruption, which had carried a number of prominent Liberals, among them Samuel Hume Blake and John Stephen Willison*, to the Tory side. At the same time Whitney possessed a superior party organization and was unfettered by ties to Ottawa or by religious divisions. He had also sounded much more the imaginative reformer than Ross when he talked of a policy on public power, help for the University of Toronto, and honest administration.

Any politician, in order to have a significant degree of success, must of necessity grow with his job; Whitney, confounding some of his critics, had done just that as leader of the opposition, and he would fill out even further as premier. When he had been selected to lead the province’s Tories, John Ross Robertson of the Toronto Evening Telegram had snidely pronounced that a stone thrown through the window of any country barrister would have hit a better man on the head than the Morrisburg lawyer. By 1905 Whitney had proved him dead wrong. As premier, he capped his electoral triumph that year with an exceptionally strong cabinet that ultimately encompassed men from all regions of Ontario and all the major denominations, including two Roman Catholics, Foy and Joseph-Octave Réaume*, a Franco-Ontarian. Subsequently, in managing his cabinet, which had its full share of competence, personality, and ego, he proved a firm, self-confident leader when facing contentious issues, and his brusque words, quiet humour, calculated annoyance, or steady glare were generally sufficient to calm or cow the unruly, even the flamboyant Adam Beck*.

Once in the premier’s chair, Whitney was to be dislodged only by death. He was returned to power in 1908, 1911, and 1914, securing in the process a stranglehold on a majority of Ontario voters and a preponderance of seats. He had travelled a long distance from his by-election triumph in 1888, a time when politics had been coloured by seemingly endless squabbles that related to religious differences. And the province, now held by the Tories for the first time since confederation, was considerably different. Numbering about two and a quarter million inhabitants, it was well launched along the route of industrialization, possessing almost one-half of all capital invested in the nation’s manufacturing. Whitney’s skilful attempts, in the complex battle for public hydroelectric power, to reconcile the opposing groups, partly to avoid the collapse of private interests, and his steady efforts to preserve the confidence of Canadian and British financial communities, were of considerable importance.

There was a dark side to this picture of economic buoyancy. Conditions of work were often harsh, job security was virtually unknown, and social assistance was administered by municipalities in irregular and parsimonious fashion. In farming, which remained of large consequence in Ontario’s economic and social picture, mechanization and increased farm size helped contribute to the rural depopulation that had been promoted by industrial activity in the cities and towns. It was a time of change when the member for Dundas became premier, and Whitney, whose autocratic temperament obscured a fine capacity for taking the public’s pulse, was attuned to that change.

One of Whitney’s first concerns in his new role was to tackle the problems that surrounded the University of Toronto [see James Loudon]. Such immediate attention was undoubtedly due to Meredith, who was still chancellor. The university had a history of being hamstrung by limited provincial funding while, at the same time, Queen’s Park meddled in its administrative affairs. Whitney moved on the initial difficulty in his first session by granting money – with more to come in the future – to permit the institution to proceed with a building program and advance toward financial stability. He followed up in October 1905 with the appointment of a prestigious commission headed by Joseph Wesley Flavelle* to investigate and make recommendations upon the management and government of the university. When this body delivered its report in 1906, the premier acted quickly to produce legislation which marked acceptance of almost every major recommendation. The result was a new board of governors appointed by the government but free from political interference, a presidential office with greater power, and an initial annual grant of a quarter of a million dollars. Whitney’s actions, which provided the institution with a solid foundation for growth, represented a complete break from the suffocating Liberal policy on higher education [see Sir Daniel Wilson*].

Three months before Whitney had ordered the study of the university, he had set up a commission to investigate virtually all aspects of hydroelectric power in the province: source, production, cost, transmission, and distribution. Adam Beck, a charismatic proponent of public power and a headstrong cabinet minister, chaired this body, ably assisted by a professional engineer and acknowledged expert in the field, Cecil Brunswick Smith. Within a year the government had three reports from this group to consider, plus one from the commission appointed by Ross to investigate the feasibility of municipal cooperation in the transmission and distribution of power. Within cabinet there was undoubtedly a sharp struggle as its members worked to translate a policy into legislation; outside the legislature pressure from private power interests was resisted by Whitney in generally conciliatory but sometimes surly fashion. The net result in 1906 was legislation creating the permanent Hydro-Electric Power Commission of Ontario, which was given sweeping powers to acquire any needed lands, waters, water-power, and installations; to arrange contracts with municipalities; to control rates set by generating and distributing companies; and to employ, if necessary, the tool of expropriation with respect to private power companies. Beck became chairman of the new commission; the other members were Smith and John Strathearn Hendrie*, another cabinet minister, whom Whitney chose to balance Beck’s radical populism.

Although one private concern, the Electrical Development Company, battled this government venture at every turn, the public did not share its views and 19 municipalities, including Toronto, voted in 1907 to empower their councils to negotiate contracts with the commission for the delivery of hydroelectricity. The following year the commission signed a contract for the construction of a transmission line from Niagara to Dundas, with branches to Toronto and municipalities in the southwest. Meanwhile, legal challenges inspired by private power interests were being mounted over the right of municipalities to enter into such contracts. Whitney responded with legislation which stayed all legal action and validated all contracts between the municipalities and the commission. Such action brought on a spate of bitter criticism to the effect that Ontario was headed down the road to socialism, a charge Whitney rejected in 1909 as a “ghastly joke.” To his mind, he was simply making for an orderly advance to the goal of public power, which was symbolized in the autumn of 1910, when power was transmitted over commission lines from Niagara to Berlin (Kitchener) for a switching-on ceremony. No other province, or state, committed itself as fully to public control of electricity as did Ontario.

Government intervention in the economy did not stop with the power commission. Owing in part to an acrimonious dispute between Toronto and outlying radial railway lines, whose owners sought easy access to the city, Whitney’s government was obliged to enter the field of railway regulation. An additional push came from the fact that, as things then stood, it was necessary to have separate legislation for almost every railway question that came before the legislature, a time-consuming means of government. Consequently, in 1906, the administration produced two pieces of legislation. The first addressed the relationships between the urban rail-fines and the municipalities and ordered the standardization of equipment and the improvement of safety; the second created the Ontario Railway and Municipal Board to enforce the initial railway legislation. The board was also granted broad powers to approve or deny municipal annexations, to confirm municipal by-laws dealing with finance and public utilities, and to serve as an arbitration board in any railway strike or lockout. In taking such action, the government had erected a type of board, completely outside the legislature, that had not been seen before in Ontario’s history, and this initiative marked a new step in the governance of the province. In its early existence, however, the board was not an outstanding success; in the case of the violent Hamilton street-railway strike of November 1906 [see John Wesley Theaker] the premier had to order the board to become involved.

On balance, Whitney enjoyed the combative aspects of politics. J. S. Willison would later recall that in the legislature Whitney, unlike George W. Ross, “spoke without preparation and was often carried into violence and extravagance of statement. But he was so transparent that the people understood and rejoiced in his tempestuous ebullitions.” If anything dulled Whitney’s enjoyment, it was prohibition – for the simple reason that, as he saw it, neither the proponents nor the opponents of absolute aridity were ever satisfied with government action. He tried for compromise in an area where compromise was unacceptable. Whitney was convinced that province-wide prohibition was out of the question and that local prohibition had to have majority support in order to be effective. When William John Hanna, his Methodist provincial secretary, introduced new liquor legislation in 1906, much of it reflected Whitney’s thinking. Under this measure licence fees for taverns and shops were dramatically increased on a graduated scale tied to population. A host of lesser regulations were all designed to tighten control of alcohol sales. In a municipality 25 per cent of the electors could call for a vote on local option, and then 60 per cent had to indicate approval before the local council could legislate local prohibition. Although prohibitionists were particularly upset with the 60 per cent requirement, Whitney would not be moved because he wanted a clear show of support for local prohibition to ease its implementation. And there the regulation of alcohol stood for the balance of his career.

Beyond these important and time-consuming measures, the Whitney government moved in several other ways in 1906–7 to alter circumstances significantly in Ontario. A commission was appointed in 1906 to investigate school textbooks. It would report a year later that prices were too high – a by-product of the failure to call for tenders – and that the books were inferior in quality to British and American ones. The government would move quickly to the tender system. In 1906 as well Robert Allan Pyne*, the minister of education, forced an increase in the salaries of rural teachers and moved to eliminate model schools and expand the number of normal schools, all in an effort to raise pedagogical standards. Some reform was also undertaken in the area of timber administration [see Aubrey White], but this was offset by a failure to provide for the enforcement of conservation legislation. Thrust into prominence by a flurry of mining activity in northern Ontario, including the Cobalt boom of 1905, Francis Cochrane, Whitney’s first minister of lands and mines, produced an act in 1906 that standardized provincial mining law. The following year, to replace an ineffectual system of royalties, he introduced legislation which provided a new formula for taxing the mining industry, an action that produced noisy protests. And there were new and stiffer penalties for proven corruption in electoral activity. Whitney impressed Ontarians with his sense of honesty and integrity. He openly denounced the practice of pork-barrelling and found the steady clamour for appointments distasteful. Though widespread patronage continued to be a partisan instrument [see John Irvine Davidson*], Whitney tried to use it discreetly and to curb its excesses. There were some areas that the reforming hand of his government did not touch, however. The premier did little to ameliorate life for the urban poor, a chore he left to public and private charity at the municipal level, and he would not be moved by frequent and articulate appeals to extend the provincial franchise to women – politics was properly a male preserve.

A month after Whitney’s sweeping electoral triumph in June 1908, he was knighted when the Prince of Wales, who was visiting Quebec for its tercentenary, conferred honours bestowed by his father, Edward VII. (This was not the first time that Whitney had received formal recognition, for he had been awarded honorary degrees in 1902 and 1903.) He took the opportunity to speak of Canada as a “great auxiliary kingdom within the Empire,” a definition which, to his mind, allowed for national development with the very necessary retention of a British connection. Because of his commitment to the imperial concept, Whitney was periodically annoyed with Britain for playing to the United States at the expense of Canada and with Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier for failing to press for free trade within the empire. Anxious to ensure that the tie was in no way weakened, he kept a watchful eye on imperial developments. Thus, in 1909, when the British-German naval race led to a debate in the Canadian House of Commons, he supported the creation of a Canadian navy and thought that his country should also be prepared to give one or two Dreadnoughts to Britain. When Minister of Finance William Stevens Fielding* introduced proposals for reciprocity in the commons in January 1911, Whitney was quick to condemn, seeing in them the threat of political union with the United States. This condemnation was reinforced in a formal resolution supported by the Tories in the Ontario legislature. After the federal Liberals were forced to call an election on the issue, Whitney threw himself, his cabinet, and his political organization into the fray. As well, he grudgingly permitted Conservative mlas to contest federal seats, and they did so with remarkable success. There is little doubt that Whitney and his machine were significant factors in Robert Laird Borden*’s triumph in Ontario. The federal chief acknowledged this support by consulting with Whitney about the composition of his cabinet.

Whitney followed Borden’s victory with an easy one of his own in 1911, but during the campaign the issue of Ontario’s French-language schools, though not a central matter, threatened racial and religious harmony within the province. Signs of difficulty for the government on this issue, which had also plagued G. W. Ross when he was minister of education, had become apparent in 1910. There was a growing conviction among some English-speaking Catholics, particularly those in proximity to their French-speaking religious brethren, that bilingual schools existed more for the preservation of nationalism than religion. This feeling was prevalent in the eastern Ontario diocese of Alexandria and it was particularly acute in the Ottawa area, where Irish Catholics had been pushed into a minority position in their church and schools by French-speaking Ontarians. Questions were raised about the quality of instruction in such schools, especially concerning instruction in English.

Franco-Ontarians were well aware of the deficiencies in their schools. In 1910 the Congrès d’Éducation des Canadiens Français de l’Ontario aggressively pressed the government for approval of a rational program for bilingual schools, for the establishment of bilingual normal schools and secondary institutions, and for a redivision of taxes between separate and public schools. Militant Protestants reacted with calls for the wholesale rejection of these demands. English-speaking Catholics, who thought they might be on the verge of improved financing for their schools, were nearly as irritated. Bishop Michael Francis Fallon* of London took up the concerns of this group and called for the elimination of bilingual schools. In the face of a verbal torrent from all sides, Whitney asked Francis Walter Merchant*, chief inspector of schools, to investigate the province’s bilingual schools. Merchant’s report, which arrived in 1912, safely after the provincial election of the previous year, contained few surprises. At its core were the hard facts that many teachers were under-qualified and that English-language instruction in the schools was a hit-or-miss affair. Merchant recommended that French be the language of instruction only in the lower grades, that English gradually be introduced to replace French in the upper grades, and that steps be taken to improve the quality of teaching.

Whitney and the Department of Education went considerably beyond Merchant’s proposals with “Circular of Instructions, 17,” to be adhered to in the school year 1912–13. With some allowances made for children already in school, it called for an end to instruction in French after the first form. The regulation generated an exceedingly divisive battle between, on the one side, the government and the bulk of Ontario’s English-speaking residents, including Catholics, and, on the other, many of the province’s French-speaking minority plus the francophones and press of Quebec. In the middle stood a few pedagogues, among them superintendent of education John Seath, who doubted whether it was feasible to teach sufficient English in the three years of first form to enable it to replace French as the language of instruction. The government was convinced that it was doing the best thing possible for the children of Franco-Ontarians and that it was moving to correct a deplorable situation. As premier, Whitney could not understand the aspirations of French Canadians or the anger the new rules produced. After a year of protests, walk-outs by pupils, and refusals to comply, the government retreated in 1913: for the pupil who had not sufficiently mastered English by the end of the first form, French could remain the language of instruction. But the damage had been done and aroused French Canadians would cite Regulation 17 as an instance of English Canadian oppression for years to come [see Philippe Landry]. It was unfortunate that Whitney, who had laboured so hard to overcome the impact of religious questions on his party, should have presided over Ontario when this dispute came to the fore.

In the latter days of Whitney’s regime there were other matters to concern him in addition to imperial relations and bilingual schools. After its election in 1905 the government had paid some attention to labour politics, but few effective steps were taken to increase industrial safety. It did, however, address the question of workmen’s compensation. Under existing law injured workers were required to prove negligence on the part of employers. In 1910 Whitney appointed his old mentor, Sir William Ralph Meredith, to examine the complex matter of injury and liability and prepare legislation based upon his findings. Meredith heard briefs from all sides and travelled to England and Europe to examine schemes in operation. He drafted legislation which Whitney meant to table in 1913 but did not, because of opposition from employers to the proposal that workers be exempted from paying into the compensation fund. Their objection was resisted and the legislation was brought forward in 1914; however, illness prevented Whitney from attending the session and personally introducing the measure, which others piloted through parliament. Condemned by manufacturers as socialist legislation, the act provided for the creation of a workmen’s compensation board to administer what the Industrial Banner (Toronto) labelled “the most far reaching legislation that has ever been enacted by any Government in Canada in the interests of labour.”

When the legislative session of 1913 had ended in May, Whitney was exhausted and his condition did not improve substantially over the next few months. To secure a complete rest he headed south of the border late in the year, but was struck by at least one heart attack. After an initial period of recuperation in New York City, he was moved in January 1914 to the new Toronto General Hospital building, which existed thanks to his government. His convalescence proceeded so favourably that he contemplated calling a June election, which party stalwarts knew would be his last political hurrah. He appeared at just one public meeting, an emotion-packed gathering in Massey Music Hall in Toronto, but the electorate rewarded him handsomely at the polls. Though he began to show some of his old vigour that summer, his body could not sustain his demands on it and he died seven weeks into World War I.

J. P. Whitney’s death marked the end of a remarkable era in Ontario politics, one that had witnessed significant legislation on such diverse subjects as the University of Toronto, workmen’s compensation, temperance, hydroelectric development, and urban transit. The eastern Ontario farm-boy had, with tutelage from Meredith, moved the government into new areas which acknowledged the growing urbanization of the province. In a time when politicians had a great deal of freedom to offer innovative legislation, he had used the state as an instrument to improve the lives of Ontarians.

Much of the above is based on Whitney’s papers at the AO (F 5 and RG 3–2). Other useful collections, all at the NA, include the papers of Borden (MG 26, H), W. L. Mackenzie King (MG 26, J), Laurier (MG 26, G), Macdonald (MG 26, A), and J. S. Willison (MG 30, D29). Further sources are cited in the author’s study “Honest enough to be bold”: the life and times of Sir James Pliny Whitney (Toronto, 1985).

Cite This Article

Charles W. Humphries, “WHITNEY, Sir JAMES PLINY,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 12, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/whitney_james_pliny_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/whitney_james_pliny_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Charles W. Humphries |

| Title of Article: | WHITNEY, Sir JAMES PLINY |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | February 12, 2026 |