Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

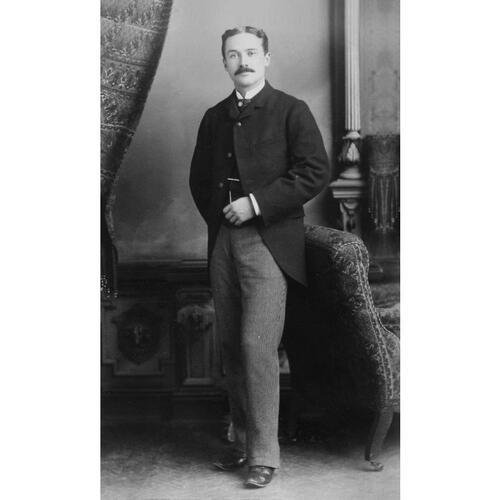

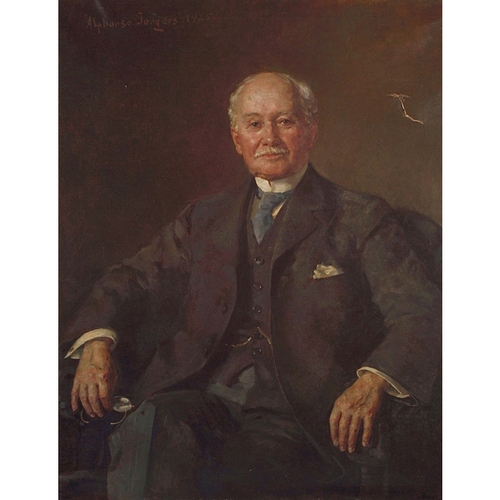

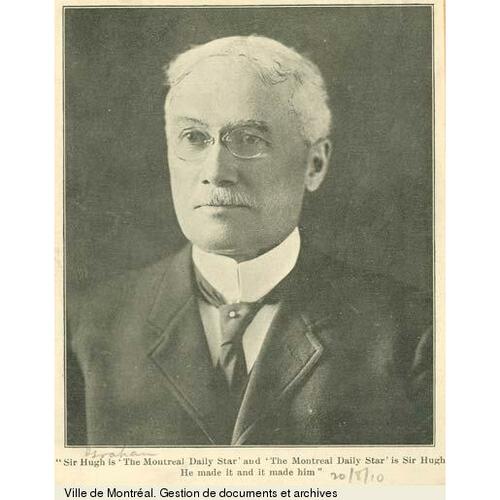

Graham, HUGH, 1st Baron ATHOLSTAN, newspaper publisher, businessman, and philanthropist; b. 18 July 1848 in St Michaels (Athelstan), Lower Canada, eldest of the four children of Robert Walker Graham, a gentleman farmer, and Marion Gardner; m. 17 March 1892 Anne Beekman Hamilton (d. 1941) in New York City, and they had one daughter; d. 28 Jan. 1938 in Montreal and was buried in Mount Royal Cemetery in Outremont (Montreal).

Born in the Châteauguay valley close to the American border, Hugh Graham attended the local school in Hinchinbrook (Hinchinbrooke) and spent two years at Huntingdon Academy. He started his working life at age 14 or 15, when he moved to Montreal to take up a position in the business office of the Evening Telegraph and Daily Commercial Advertiser, where his uncle Edmund Henry Parsons was editor and publisher. The paper was sold and Graham, who had worked there as a bookkeeper and as business manager, moved on to the Gazette sometime in late 1867 or in 1868. There he was thrown into the company of the sports editor, George Thomas Lanigan. Only two and a half years older than Graham, Lanigan had already made a name for himself as a poet, writer, and journalist. In addition to his work at the Gazette, he had founded in 1867 a satirical weekly called the Free Lance. When the Free Lance ran into financial difficulties, Lanigan turned to Graham for help. On 1 Dec. 1868 they became partners; Graham was to handle the business end of the enterprise and Lanigan the editorial. They would continue to publish the Free Lance until March 1869. Out of this partnership was born the Evening Star, which was first published on 16 Jan. 1869; it would change its name to the Star on 16 April 1877 and then to the Montreal Daily Star on 3 Jan. 1881, and would continue under variations of that name until 25 Sept. 1979.

In later years Graham would often boast that the paper’s owners had survived the early period with nothing but pluck and old-fashioned industry; the two partners had less than $100 between them and $1,000 in borrowed capital. The truth is that they were not quite so heroic. The details are sketchy, but at the beginning the paper was owned by the firm Marshall and Company, which may have consisted of Graham, Lanigan, and another young journalist, Thomas Marshall, although Marshall’s role is not clear. Other sources suggest that from early on Graham was the sole proprietor of Marshall and Company. Certainly, the first year or so was difficult, marked by the dodging of creditors and by creative improvisation when the press broke down. At the end of six months there was a financial crisis, but Graham was able to draw on the support of his family and he received in September or October at least $3,000 from his father and smaller amounts from other relatives. The price for this backing seems to have been the instalment in November of Parsons as the sole editor. Lanigan was probably viewed as too Bohemian and too pro-American by the staunchly British and Presbyterian Graham clan. He left the paper, but would write articles for the Star for several months before settling permanently in the United States.

The financial assistance from his family may have enabled Graham to restructure ownership of the paper. In October he had created Graham and Company, with advertising salesman Wayne Griswold, to publish the paper; he retained seven-eighths of the shares. The firm would be dissolved in 1873. After participating in brief partnerships in 1881–84 and 1884–87, again under the name Graham and Company, he would continue alone as publisher.

When the Star was launched early in 1869, Montreal already had seven dailies, four English-language and three French-language, despite the fact that French speakers had recently become marginally more numerous than English speakers. The papers were identified with political or religious factions and, as a result, catered to relatively small readerships. By offering an alternative to their long-winded partisan articles, official announcements, and dry commercial news, the Star, like the populist New York dailies it emulated, sought to tap the new mass market created by increased urbanization and working-class prosperity. The marketing plan of these newspapers, for which the Star would set the pattern in Canada, aimed at a wider audience and was built on more varied fare, with something for everyone, but particularly for segments of the population that had hitherto been ignored – women, workers, immigrants (especially the Irish), and sports enthusiasts. As one of its advertisements boasted early in 1869, the Star was “the paper for everybody, rich or poor, in the city, or in the country, Protestant or Catholic, Blue or Red.”

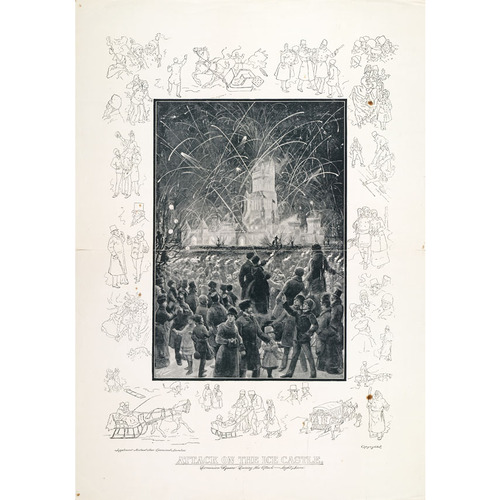

This new content was dressed up in livelier language and had a strong human-interest element, even a racy tinge. One of the early successes, almost certainly written by Lanigan, was a front-page series called “Days and nights,” which included seamy details of prostitution in Montreal, while claiming that “we mean good. We wish to ventilate the absurd Romance of vice, to show sin in its everyday life and aspect. We wish society to know what the evil is, that it may be wise to shun its tempting commencement, and its awful ending.” Lanigan and Graham wanted news that had an immediate visceral appeal so that the paper could be hawked in large numbers on street corners for a penny a copy, whereas the owners of competing publications were content with the smaller but steadier circulations engendered by pre-sold subscriptions. Vigorous self-promotion was also part of Lanigan and Graham’s marketing plan. But above all, the Star tried to provide good value, publishing more pages than its competitors and introducing lavishly illustrated special issues at Christmas and during winter carnivals.

By the mid 1870s the Star was outselling its competitors and clear of debt. In 1887 it claimed a circulation of 27,746, the largest in Canada. Even after La Presse (Montréal) moved ahead in daily circulation in the mid 1890s, the Star remained the best-selling English-language daily in Canada (a position it was to maintain well into the next century) and it had the greatest combined daily and weekly circulations of any paper in the country. Worth about $250,000 in 1895, it was considered the most lucrative newspaper property in Canada and it brought in $40,000 a year to Graham.

The weekly edition of the Star, called the Family Herald and Weekly Star, founded in 1870, played a prominent role in the paper’s success. By 1895 it was selling 70,000 copies, more than half in Ontario and the Maritimes, which gave the Star impressive clout well beyond its home market. Graham built this unprecedented circulation by underselling his competitors, especially in the rural markets, where readers could subscribe to the Weekly Star for just one dollar a year.

Whereas other publishers were beholden to special interests or placed at least as much emphasis on their political or social mission as on their provision of news, Graham concentrated on expanding his business and was free to make his journalistic decisions without reference to anyone. His spectacular achievement provided a model for people’s dailies elsewhere, such as John Ross Robertson*’s Evening Telegram (Toronto), Philip Dansken Ross*’s Evening Journal (Ottawa), and Trefflé Berthiaume*’s La Presse, and set in motion the wheels that turned creaky 19th-century political-party presses into modern media corporations.

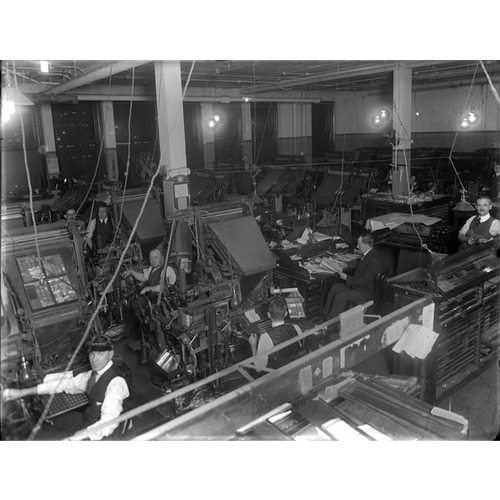

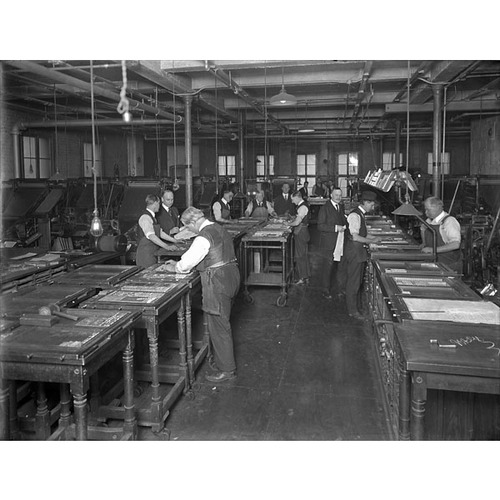

Never himself a journalist, Graham was content to pull the strings that made it all happen. An astute and innovative manager, he hired talented staff, including artist and political caricaturist Henri Julien* and journalists who would later achieve national prominence, such as P. D. Ross and John Wesley Dafoe*. Several editors, among them Edward George O’Connor, Henry Dalby, Albert Richardson Carman, and A. J. West, would work with him for many years. He constantly reinvested profits in the latest technology, such as the first web-offset press in Canada (1874), which printed on paper fed from a roll rather than on precut sheets, and a direct telegraph line to the newsroom. He was also the first to publish accurate circulation figures (1884) and to integrate different aspects of his business by purchasing a paper mill, the News Pulp and Paper Company Limited of Saint-Raymond, in the early 1900s. With Robertson in 1902, he founded the Canadian Associated Press, which established the first Canadian newspaper cable service directly from Great Britain.

Promoting itself as “The Paper of the People!” and boasting that it was “Independent, Free, and Fearless,” the Star had fought the monopoly of the Montreal Gas Company and had spearheaded efforts in 1883 to establish an alternative, the Citizens Gas Company of Montreal. It exposed local merchants who charged exorbitant prices and organized shovelling brigades when the city was hard hit by snowstorms, but it probably got most worked up in its crusades to improve the health of citizens. One of the Star’s most notable campaigns occurred during the smallpox epidemic of 1885 and 1886, which killed some 3,000 Montrealers, many of whom succumbed because of ill-informed opposition to inoculation. Graham not only used his paper to keep up a constant barrage of educational articles and the latest information, backing the efforts of the chairman of the city’s Board of Health, Henry Robert Gray*, but he also became personally involved as a member of an expanded health board. The Star crusaded against corruption in Montreal’s civic administration and congratulated itself for its role in the election of John Joseph Caldwell Abbott* to the mayor’s office in 1887. That year it established the Fresh Air Fund to send inner-city children to summer camps. Over the years Graham would fight to obtain regulations for the pasteurization of milk, mount campaigns to eradicate cholera, typhoid, and tuberculosis, and offer a prize (unclaimed) for a cure for cancer. These initiatives followed the example of James Gordon Bennett, editor of the New York Herald, and the owners of other crusading American dailies; such tactics also fitted perfectly with the Star’s marketing strategy as a populist newspaper.

During the North-West rebellion of 1885, the Star had pulled out all the stops, sending seven reporters into the field. This was one of the first uses of saturation coverage for major stories that would become in later years the working method of other papers, notably the Toronto Daily Star. The effort resulted in some memorable articles, particularly William Arthur Harkin’s jailhouse interview with Métis leader Louis Riel*, published on 22 August together with a brief message from Riel to the paper’s readers.

Although the Star had always claimed to be an independent publication, from the late 1870s onward Graham himself had been identified with the Conservative Party, and the Star had consistently supported Conservative and imperial causes. Graham viewed Britain as his cultural homeland and British achievements and institutions as the pinnacle of civilization, but he nonetheless considered Canada an independent nation that should demonstrate its maturity by participating in imperial matters as an equal with the mother country. In the period leading up to the South African War of 1899–1902, he gave full vent to his leanings with extravagant patriotic rhetoric about going to the aid of the motherland in her time of need. Not content merely to report the news, in early October 1899 he had his staff send some 6,000 telegrams to public figures across the country to solicit messages urging the necessity of Canada’s involvement. He hoped the replies would railroad the reluctant Liberal government of Sir Wilfrid Laurier* into the war. With headlines such as “Our country must be kept British,” which appeared on 11 October, the Star’s pro-empire position antagonized nationalists from the province of Quebec, such as politicians Joseph-Israël Tarte* and Henri Bourassa*. Many opposed what they considered to be an unjust colonial war; others deplored the fact that parliament and the electorate were not being consulted. Conservative leader Sir Charles Tupper*, who had brought Graham into the party’s corridors of power around 1896, believed that the publisher had saved Canada’s honour in the months before the war. The Star’s campaign and Graham’s personal pledge to provide up to $1,000,000 of insurance for the Canadian volunteers of the first contingent sent to South Africa contributed greatly to Canada’s eventual involvement [see Laurier], but they also helped to widen the gulf between Conservatives and nationalists as well as between French Canadians and the rest of the country.

Although Graham was noted for being tight-fisted with his employees, he was more than generous in the use of his newspaper and his wealth to support or advance Conservative Party initiatives. From 1896 until at least 1904 he was a key fund-raiser and adviser, particularly in the Quebec branch of the party. In correspondence with Conservative prime minister Sir Robert Laird Borden in 1917, he would claim to have spent more than $200,000 on the 1904 election alone, some of it in the form of loans, most of which had not been repaid. In a note to Prime Minister Richard Bedford Bennett* in 1932 he would assert that he had given more support to the party “than any other three men in Canada,” a total of $1,400,000, according to his estimate.

As Graham’s wealth and power grew, he seems to have taken more and more seriously his self-image of senior statesman. Certainly, as the nation’s pre-eminent newspaper publisher and a generous party backer, he could not be ignored, but his real influence steadily waned, and after 1904 he began to be seen more and more as a loose cannon, someone whose goodwill, financial backing, and clout in the media were worth keeping, but also someone whose advice could not be trusted in important matters.

Much of his loss of personal influence was owing to his questionable judgement in efforts to manipulate elections and policies. His involvement in the 1904 federal election is an example of his lack of discernment. Graham, financier David Russell, lawyer James Naismith Greenshields, and former politician Andrew George Blair* were key conspirators in a plan to undermine Prime Minister Laurier and the Liberals in Quebec by bribing journalists, urging Liberal candidates to resign, and, most importantly, secretly acquiring La Presse for the sum of $825,000 and using it to question, in the guise of a supporter, Laurier’s platform and record. The paper was surreptitiously bought with money raised by Graham and others, but Laurier learned of the scheme and threatened to reveal it, thereby foiling the plot [see Berthiaume]. Borden, leader of the Conservative opposition at the time, felt obliged to deny rumours he had been involved and to distance himself from his party organizers in Quebec, including Graham.

Graham’s attempts to meddle with the political process often entailed extravagant plots of an almost theatrical nature. Borden, who generally saw through these stratagems, would characterize Graham in his diary in 1916 as “a singular mixture of cunning and stupidity. His great weakness lies in his belief that he can hoodwink others.” One of Graham’s favourite ploys was to write drafts of letters that he sent to prime ministers and other influential figures with the request that they sign as if the expressed ideas were their own. Although often rebuffed, he never stopped offering advice to prime ministers, from Sir John A. Macdonald* to Bennett, or seeking favours such as postal or tariff reductions for his newspapers. Despite Graham’s close ties to the Conservatives, it was a Liberal prime minister, Laurier, who recommended him for the knighthood he obtained in 1908, after Graham had adopted an uncharacteristically non-partisan stance during the federal election campaign of that year.

Despite the waning of Graham’s personal credibility, his newspaper still carried much clout. Its power was spectacularly demonstrated during the federal election of 1911, when the Star drummed up opposition to Laurier’s reciprocity agreement with the United States [see William Stevens Fielding*]. One of the Star’s tactics was to print and distribute through Conservative newspapers across the country some 300,000 copies of a special supplement arguing against reciprocity. The addition featured contributions solicited from influential imperialists such as the writer Rudyard Kipling. John Castell Hopkins* remarked in the Canadian annual review that “it is not very often in the history of a young, or indeed of any country, that a single newspaper wields a powerful influence in the overturn of a Government and the defeat of a political policy. Such, however, was the record of the Montreal Star in 1911.”

Although Graham had mended his fences with the Conservatives by helping them win the general election, it was not long before he complained to Prime Minister Borden that he was being ignored by those in the seats of power, despite his stellar service to the cause. In the build-up to World War I, he urged Borden to make a substantial Canadian contribution to the imperial navy, but his efforts came to naught when the Senate rejected the Naval Aid Bill in May 1913 [see Sir James Alexander Lougheed*]. After the outbreak of war, when volunteer enlistments failed to meet manpower needs, Graham became a vociferous supporter of conscription. The Star’s virulent attacks against French Canadians were considered inflammatory and racist by many in Quebec, and Graham became the target of fervent anti-conscriptionists. Fuelled by agents provocateurs, they would dynamite his summer residence in Cartierville, a suburb of Montreal, during the early morning of 9 Aug. 1917. There would be minor damage and no injuries. That year Graham, who had consistently boosted imperial endeavours in Canada, would be granted a peerage as Baron Atholstan for “extraordinary initiative and zeal in promoting and supporting measures for safeguarding Imperial interests.”

In 1913 Graham secretly helped to finance a new Liberal paper, the Daily Telegraph and Daily Witness, which absorbed a direct competitor, the Montreal Daily Witness. He had also covertly acquired the Montreal Daily Herald, which purchased the Daily Telegraph and Daily Witness in January 1914. During the war years Graham, who had crusaded against monopolies and trusts, used his fortune and connections to eliminate other Montreal newspapers. He apparently drove Edward Beck, one of his former editors, out of business by shutting off supplies of newsprint for Beck’s Weekly, and he did the same to other competitors. According to the Star’s 100th-anniversary publication, Graham had “exercised a determined hand” in the demise of a number of the city’s English-language papers.

In the 1920s Atholstan’s relations with the Conservative Party leaders, in particular Prime Minister Arthur Meighen*, reached their nadir. With other Montreal businessmen, including representatives of the Bank of Montreal and the Canadian Pacific Railway, he opposed Meighen’s policy of nationalizing railways and considered the prime minister to be too influenced by Toronto financiers and power brokers. On 30 Nov. 1921 the Star printed a roorback (a falsehood published for political effect), which purported to be inside government information. It concerned changes in the administration of the government railways, which would result in Montreal’s loss to Toronto of much of its economic power as a railway centre. The rumour was picked up by the Quebec Liberals to great effect, and Meighen apparently believed that Atholstan had cost him the election.

During the years that followed Atholstan continued to undermine Meighen. In 1923 a series of editorials entitled “Whisper of death” suggested that Meighen had strayed from traditional Conservative principles, which necessitated a change of party leadership. Five years later the former prime minister wrote that Atholstan’s “degree of sagacity and judgment … in public affairs has been a converging minimum which long ago passed the zero point.”

Towards the end of his life, the energetic people’s crusader of the 1880s had become a weakened, though not altogether spent, force, an elitist millionaire manipulator and back-room schemer increasingly at odds with the populist values that had propelled his newspaper to success. In his later years, Atholstan travelled extensively and became noted for his philanthropy, favouring religious and educational organizations and causes such as health care and provision for the aged. In 1925, without a male heir to take over his business, he secretly sold the Star to Montreal businessman John Wilson McConnell* for $1,500,000, with the stipulation that he would continue to exercise control until his death, which would not occur for another twelve and a half years.

Atholstan was the first and most successful of the entrepreneurs who ushered in the modern newspaper age in Canada. His contributions to the development of the press are indisputable, but his lasting impact on Canadian politics is less certain. There is no doubt that he aspired to the role of an éminence grise and used his wealth and newspaper to force his way into the corridors of power. But there, his imperialist views were already becoming anachronistic as Canadians aspired to throw off the vestiges of colonialism. A secretive and manipulative man by nature, he was more often ridiculed than revered by those he sought to influence, even as they courted his journalistic and financial support. What many failed to recognize, however, was that his often-convoluted stratagems were meant to distance Atholstan, the back-room politician and schemer, from the ostensibly independent Montreal Star. The power of the press to a great measure depends on its being seen as uncompromised by partisan affiliations, and Atholstan, above all an astute publisher, owed much of his success to never losing sight of that fact.

BANQ-CAM, CE601-S130, 17 mars 1892; CE607-S35, 1er févr. 1849; TP11, S2, SS20, SSS48, vol.1c, 29 avril 1881, no.188, 19 févr. 1884, no.243; vol.1 P.S., 22 févr. 1888, no.807; vol.3-O, 3 mars 1870, no.5045; vol.5-O, 23 juin 1873, no.6684; vol.6 P.S., 23 mai 1904, no.917; vol.11-O, 26 mars 1884, no.350; vol.13-O, 22 févr. 1888, no.973. LAC, MG 26, A; F; I; R6113-0-X; R10811-0-X; R11336-0-7. Free Lance (Montreal), 1867–73. Montreal Daily Star, 1869–1938. R. L. Borden, Robert Laird Borden: his memoirs, ed. Henry Borden (2v., Toronto, 1938). R. C. Brown, Robert Laird Borden: a biography (2v., Toronto, 1975–80). Canadian annual rev., 1911. The Canadian newspaper directory (Montreal), 1892. A. H. U. Colquhoun, “The man who made the Montreal Star: Hugh Graham, esq.,” Printer and Publisher (Toronto), 4 (1895), no.4: 6–7. Directory, Montreal, 1867–70. Roger Graham, Arthur Meighen: a biography (3v., Toronto , 1960–65), 2. John Gray, “Our first century – a lot of it was fun,” in The “Montreal Star”: one hundred years of growth, turmoil and change, 1869–1969 ([Montreal], 1969). H. G. Green and A. J. West, “Headlining a century with the Montreal Star” (2v., typescript, n.p., [1952?]; copy in Concordia Univ. Libraries, Vanier Special Coll. (Montreal)). M. E. Nichols, (CP): the story of the Canadian Press (Toronto, 1948). Paul Rutherford, A Victorian authority: the daily press in late nineteenth-century Canada (Toronto, 1982). O. D. Skelton, Life and letters of Sir Wilfrid Laurier (2v., Toronto, 1921). Minko Sotiron, From politics to profit: the commercialization of Canadian daily newspapers, 1890–1920 (Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 1997).

Cite This Article

Enn Raudsepp, “GRAHAM, HUGH, 1st Baron ATHOLSTAN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/graham_hugh_1848_1938_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/graham_hugh_1848_1938_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Enn Raudsepp |

| Title of Article: | GRAHAM, HUGH, 1st Baron ATHOLSTAN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2013 |

| Year of revision: | 2013 |

| Access Date: | January 1, 2026 |