Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

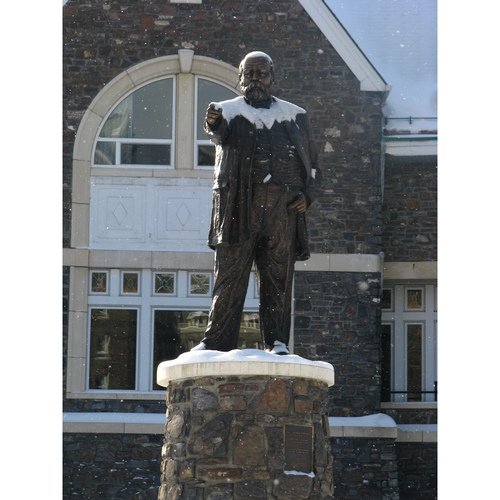

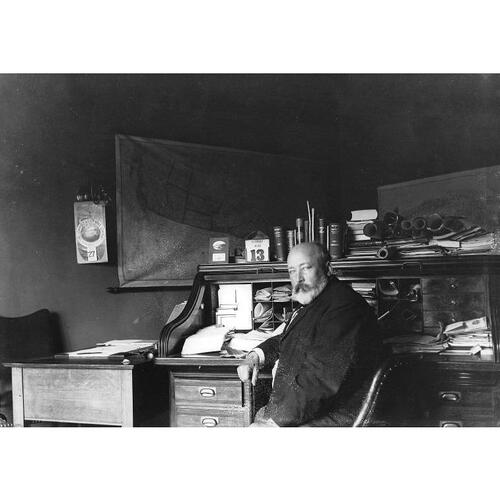

VAN HORNE, Sir WILLIAM CORNELIUS, railway builder and official, capitalist, and artist; b. 3 Feb. 1843 near Chelsea (Frankfort), Ill., eldest child of Cornelius Covenhoven Van Horne, a lawyer and farmer, and Mary Minier Richards; m. March 1867 Lucy Adaline (Adeleine) Hurd of Joliet, Ill., and they had two sons, one of whom died in childhood, and a daughter; d. 11 Sept. 1915 in Montreal and was buried in Joliet.

Dutch ancestors of the Van Horne family came to North America in the 1630s; William Van Horne’s mother was of German and French-Pennsylvanian stock. The family moved to Joliet in 1851, and when William was 11 his father died, leaving the family in poor circumstances. William took whatever odd jobs he could find. Among other tasks, he carried messages for the local telegraph company, where he learned the basic elements of telegraphy. His formal schooling ended when, at 14, he was so severely punished for drawing and circulating some unflattering caricatures of his principal that he never went back.

Van Horne obtained work in the telegraph office of the Illinois Central Railroad. He would change jobs frequently, occupying increasingly responsible positions and learning everything he could about railway operations; apparently he could decode telegraphic messages by simply listening to the clicks rather than recording and reading them. While working as a freight checker and messenger on the Michigan Central, he was so impressed when its superintendent arrived in his private car that he resolved to become a railway superintendent. His mischievous sense of humour and propensity to play practical jokes, traits that would stay with him for life, kept pace with this determination. On one of his early railway jobs he wired a metal plate in the freight yards so that anyone stepping on it received a mild electric shock. When the shop foreman became a victim, Van Horne was fired.

In 1862 he became ticket agent at the Joliet office of the Chicago and Alton Railroad. He rose rapidly in its service, becoming a divisional superintendent. In 1872 the Chicago and Alton acquired the struggling St Louis, Kansas City and Northern, and named Van Horne its general superintendent; he helped make it profitable, but it was sold in 1874. Chicago and Alton officials then appointed him general manager and, in 1877, president of another moribund railway, the Southern Minnesota; under his management it too became productive. In 1878 he took on as well the superintendence of the parent company, the Chicago and Alton. From there he moved two years later to become general superintendent of the larger Chicago, Milwaukee and St Paul.

Van Horne’s work brought him into close contact with James Jerome Hill, Minnesota’s most aggressive railwayman. In 1880 Hill and his associates, among them George Stephen* of Montreal, signed a huge contract with the Canadian government to build the Pacific railway. Two experienced American builders were appointed: Alpheus Beede Stickney as general superintendent of western construction and Thomas Lafayette Rosser as chief engineer. Construction began on 2 May 1881, but it soon became apparent to Hill, the only member of the syndicate who had practical experience building railways, that Stickney and Rosser were unable to organize work in a satisfactory manner. Not only was their progress in construction disappointing, but evidence was also mounting that both of them were engaged in private land speculations detrimental to the interests of the company. Under pressure from Hill, Stickney retired in October 1881. Hill then recommended that Van Horne be obtained to manage the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway. “I have never met anyone,” Hill had written to Stephen a week before Stickney’s retirement was announced, “who is better informed in the various departments: Machinery, Cars, Operations, Train Service, Construction and general policy which with untiring energy and a good vigorous body should give us good results.” Luring Van Horne from the Chicago, Milwaukee and St Paul had the added advantage of weakening one of Hill’s expansion-minded American rivals. Offered one of the highest salaries paid any railway manager, Van Horne accepted; he arrived in Winnipeg on 31 December and began work as general manager on 2 January.

By 1882 parts of the line had been completed. Andrew Onderdonk*, another American engineer, had signed or taken over contracts to build some of the most difficult mileage from the Pacific into British Columbia’s interior. Van Horne would have responsibility for the construction of three major portions: the section from the end of track in 1881 at Flat Creek (Oak Lake) in western Manitoba to a juncture with the rails being laid by Onderdonk; the line north of lakes Huron and Superior from Callander, Ont., to Thunder Bay; and gaps in the line between Thunder Bay and Winnipeg.

Shortly after his arrival Van Horne promised that 500 miles of track would be laid on the prairies in 1882, more than any company had ever built in a single year. He regarded speed as essential since the railway’s cash and land subsidies were earned only as portions of the line were completed, inspected, and opened. The subsidies paid for trackage on the prairies, where costs were relatively low, were needed to pay for the high anticipated costs of construction in the Rocky Mountains. In addition, the company could expect to carry little through freight, hence its earnings from operations would remain low until the main line was finished. Van Horne believed that the success of the CPR depended on the rapid development of revenue-producing services which only the completed line could offer. In order to avoid serious delays if any of the contractors or subcontractors did not meet their schedules, Van Horne organized a “flying wing” of labourers who, under his control, could swing into action to carry out the work. The American firm of Langdon, Shepard and Company did not lay the promised 500 miles: they completed only 417 miles of main line, although, if branch lines, sidings, and the laying of rails on previously graded roadbeds were included, it was still possible to claim that the full mileage had been built.

Van Horne’s experience with Langdon and Shepard was none the less sufficiently strained that they were granted no further contracts. Instead, the somewhat mysterious North American Railway Contracting Company, a shell formed primarily to attract investors and controlled by the CPR, was incorporated in New Jersey. It signed a contract with the railway under which unissued CPR stocks and bonds would be transferred to the new company if it raised the necessary funds and completed the main line. North American immediately hired two construction managers, James Ross for the mountain section from Calgary to the end of Onderdonk’s work, and John Ross (no relation) for the section north of Superior. North American, however, failed in its financial arrangements in 1883, forcing the CPR, specifically Van Horne, to become its own contractor. The Rosses retained their positions and quickly negotiated numerous smaller contracts with aspiring Canadian builders. The construction managers at the end of steel had primary responsibility, but as general manager Van Horne, who had transferred his office and residence to Montreal in 1882, vigorously reviewed the contracts and subcontracts to ensure conformity. Changes in locations, specifications, and contractual obligations also required his constant attention.

Tall and massively built, Van Horne was a man of immense physical energy, capable of ferocious drive and Herculean effort. In a crisis he could work exceptionally long hours, sometimes walking or riding by buggy over lengthy distances of rough terrain to visit construction sites. He was, moreover, capable of decisive action. Within a month of taking office he had gathered sufficient evidence regarding Rosser’s speculations that he terminated his services. Members of Rosser’s engineering staff were also replaced when it was found that some of their plans and profiles, which were of potential use to speculators, had disappeared. In Ontario, where the CPR had absorbed the Canada Central Railway, its contractor, whose progress did not satisfy Van Horne, was replaced by a vigorous protégé, Harry Braithwaite Abbott. Superintendence of the western division was entrusted to the aggressive John Egan, another former Chicago, Milwaukee and St Paul associate, in spite of loud criticisms of his Fenian sympathies. Later, in the mountains, several bad sections could not be completed in time for the driving of the last spike, so Van Horne authorized the construction of temporary track around those spots but refused the compensation demanded by the unfortunate contractors. His actions earned him a reputation as a “Napoleonic master of men,” but many contemporary descriptions of him, such as Robert Kirkland Kernighan’s account in the Winnipeg Daily Sun in 1882 of the “terror” of Flat Creek who “cuffs the first official he comes to just to get his hand in” and whose arrival at the end of steel results in a “dark and bloody tragedy enacted right there,” were products of fevered journalistic licence as the CPR was pushed forward.

Van Horne invested little of his own money in the CPR during construction, and his involvement in the financial crises which almost wrecked it in 1883, 1884, and 1885 [see John Henry Pope*; Sir John A. Macdonald*] was largely restricted to expressions of courage and determination when syndicate members and politicians seemed ready to admit defeat. In the early spring of 1885 he was not at the end of track in the Rockies when the company’s inability to pay its contractors, and rumours of impending bankruptcy, resulted in a bitter strike. However, he did warn the syndicate repeatedly of the consequences if the pay car was not dispatched, and he sent out numerous tough messages supporting the larger contractors and the North-West Mounted Police who were trying to keep the men at work [see Sir Samuel Benfield Steele]. Also that spring, when the rebellion led by Louis Riel* broke out in the northwest, Van Horne was intimately involved in the arrangements for the movement of troops and supplies over the partially completed line north of Superior. These services earned the company the gratitude of the government and, of greater importance, the subsidies and guarantees needed to complete construction of the main line. On 16 May 1885 the last rail on the Superior section was laid and on 7 November the last spike was driven at Craigellachie, B.C., by Donald Alexander Smith. Van Horne’s contribution did not go unrecognized: on 14 May he had been elected to the CPR’s board of directors and immediately afterwards he became vice-president as well as general manager.

During construction the directors had made two important decisions, one with Van Horne’s concurrence, the other because he and the government insisted on it. The first involved a change to a southerly route across the prairies and through the Rockies, using the Kicking Horse Pass (located by Albert Bowman Rogers*) rather than the Yellowhead Pass, originally recommended by Sandford Fleming. This change, for which J. J. Hill bore primary responsibility, was an attempt to guard against the diversion of Canadian traffic to the Northern Pacific Railroad, then a dangerous rival both of the CPR and of the Great Northern system, which Hill and other members of the CPR syndicate were building in the American northwest. The other decision was Van Horne’s insistence on the immediate completion of the difficult line north of Superior. The government had stipulated this route as a condition of its contract, but Hill and others on the syndicate wanted to delay and perhaps renegotiate. There was virtually no local traffic on this barren, 1,000-mile section across the Canadian Shield: operations could be profitable only if the section carried large volumes of traffic generated elsewhere. Until it was completed, all of the CPR’s construction materials for the west and almost all of its freight had to pass over Hill’s St Paul, Minneapolis and Manitoba Railroad. Uncomfortable with this dependence and with his sights set on a strong through traffic, Van Horne vigorously supported the government’s determination to have the all-Canadian route finished. At the same time, he recognized the strategic value to the CPR of access to railways south of Superior, in the United States. As president of the CPR, a position he assumed on 7 Aug. 1888 after Stephen retired, he was in a strong position to act on this perception.

Protection of CPR territory was aided considerably by the monopoly provision of the company’s charter. Persistent protests from the province of Manitoba forced the federal government to repeal the provision in 1888 [see Thomas Greenway*], but its loss facilitated a new initiative. Van Horne used funds obtained as compensation to complete acquisition of two lines south of the border: the Minneapolis, St Paul and Sault Ste Marie and the Duluth, South Shore and Atlantic. Thereafter, in any freight-rate war with an American railway, the CPR could temporarily avoid its expensive line north of Superior and use the southern lines to fight for traffic to and from the Canadian west and the American northwest. Hill viewed these acquisitions as outright invasion. A number of CPR shareholders still had substantial interests in his American lines and eventually they enforced an accommodation acknowledging the territoriality of both systems. Despite their strong respect for each other, tension between Van Horne and Hill, particularly over control of traffic to Duluth, Minn., would continue throughout Van Horne’s presidency and allegedly contribute to his decision to resign.

During the six years Van Horne had served as general manager, his greatest achievement was unquestionably the construction of the CPR’s main line and the most urgently needed feeder lines and auxiliary facilities. He maintained firm oversight and control of all major construction and operational matters, but placed trusted managers in key positions and gave them considerable autonomy. Those not enjoying his confidence were given reduced assignments or relieved of their duties.

The fate of several construction managers illustrates his methods. On the mountain section, the work of James Ross demonstrated the continuous accountability and local autonomy central to Van Horne’s system. Although there were some sharp disagreements, in which Van Horne’s opinion usually but not always prevailed, the two men respected and trusted each other. On the western portion of the Lake Superior section, John Ross was less successful and he never enjoyed Van Horne’s complete confidence. Nor did James Worthington, construction manager of the Canada Central, which would become the eastern section of the Superior line. Worthington resigned in May 1884 after a disagreement with Van Horne and in the spring of 1885 John Ross followed suit. Their places went to Harry Abbott. When arranging troop movements during the North-West rebellion, Van Horne worked closely with Abbott, then in charge of the eastern part of the Superior section, but he personally assumed responsibility for most of the arrangements on the western part, where John Ross was still directing work. After completion of the Superior line, Abbott was reassigned, in 1886, to finish and upgrade the main line in British Columbia so that it could be opened for traffic. Other key operating managers appointed by Van Horne included William Whyte, superintendent of the Ontario division until he replaced Egan after that tough, often unpopular officer resigned, and Thomas George Shaughnessy*, who had been enticed to leave Van Horne’s old road, the Chicago, Milwaukee and St Paul, to become chief purchasing agent of the CPR in 1882. A ruthless auditor, Shaughnessy kept Van Horne informed of all major and potentially troublesome developments, but he also had Van Horne’s complete trust to make the necessary and appropriate decisions pertaining to his area. Once the main line was built, Shaughnessy would prove invaluable in the operation of the CPR.

To build up traffic, Van Horne directed the fabrication of increasingly complex systems that integrated agricultural and timber lands, grain elevators, flour mills, port facilities and terminals, maritime fleets, express and telegraph operations, and passenger and tourist services, including large hotels [see Bruce Price*]. To publicize the completed CPR, Van Horne, himself an art connoisseur, did not hesitate to turn to professional artists. John Arthur Fraser* and Lucius Richard O’Brien*, among others, received commissions in the 1880s to execute paintings of the Rockies for promotional exhibitions, and the inspiring photographic work of Alexander Henderson would lead to the formation of a photography department within the CPR in 1892. At the same time, but without the nationalistic/frontier aura of its western drive, Van Horne and the CPR moved steadily to expand in eastern Canada, in direct competition with the established Grand Trunk Railway [see Sir Joseph Hickson*]. In the 1880s the CPR completed a line to Windsor, Ont., with through trains to Chicago, and a series of acquisitions and construction projects was launched to take it across Quebec and Maine to the Maritimes.

By the time Van Horne became president in 1888, the company had survived its greatest financial difficulties. During his presidency it spent enormous sums to improve the main line and to build or acquire branches linking it to the northern prairies and parts of western Manitoba. In eastern Canada links to southwestern Ontario and the Atlantic had been forged. By 1890 the basic system was complete and Van Horne, always an enthusiastic supporter of commercial, industrial, agricultural, and colonization schemes that would generate revenue-producing traffic, reluctantly agreed that the company had built too far in advance of immediate requirements. The country had to be allowed to catch up before more traffic-generating branches were launched or freight rates were lowered. Consequently there was a halt in new construction and stiff resistance by the CPR to any reductions of rates until the volume of traffic increased. This resulted in growing popular resentment of the company’s cautious policies, which, many believed, hampered rapid economic growth and development. The desired national expansion came after 1895, and the CPR responded. Van Horne had a leading role in 1896–97 in negotiations with the new Liberal government of Wilfrid Laurier over a subsidy for a line through the Crowsnest Pass into the rich Kootenay mining region of British Columbia, primarily to counter competition from Hill’s Great Northern and the Spokane Falls and Northern Railway. These negotiations led not only to construction but also to the historic Crowsnest Pass agreement, passed by parliament in 1897 and instituted the following year, which lowered CPR freight rates over the entire prairies, thus assisting the expansion of agriculture.

Van Horne was a builder, with a grand vision of what western Canada and the CPR could become, and he received much personal recognition, including an honorary kcmg in 1894. (An American citizen, he would acquire naturalized status a year before his death.) But he apparently did not find the day-to-day operations of an established and profitable railway as challenging as construction. Still full of vigour but now forced by bronchitis to spend some time in hot climates, he resigned the presidency on 12 June 1899, at age 56; he would maintain a presence as chairman of the board until 1910 and, to no one’s surprise, he became involved in other visionary development projects.

Major steam-railway construction had come to a standstill in the early 1890s in Canada, and even the most successful contractors had had to turn to related fields for work. Many found it in the electrification of street railways; Van Horne was invited to join several of these projects, in Toronto, Montreal, Winnipeg, and Saint John. Personal interest, and a concern that new Canadian urban electrification projects be integrated with CPR freight and passenger services, led to his acceptance, but he would not become dominant in any Canadian street-railway company. Many adventurous Canadian builders extended their street-railway talents to British, Caribbean, and Central and South American cities, hand in hand with such capitalist entrepreneurs as Benjamin Franklin Pearson and Frederick Stark Pearson. Van Horne was involved in projects in Birmingham, England, and in a number of South and Latin American countries, but Canadian interest in electrifying the mule-drawn tramways of Havana, Cuba, became particularly important for him after his resignation in 1899.

Cuba had been convulsed by rebellion against Spain and in 1898 the United States intervened, establishing a temporary military government. In an attempt to block undue pressure from the swarms of promoters and financial buccaneers attracted by this occupation, the American government enacted legislation that prohibited new charters but did not prevent the acquisition of existing ones. Even before the military government was ensconced, three syndicates were vying for control of Havana’s tramways. Van Horne, who traced his involvement to an encounter with Cuba’s minister in Washington and who knew several key American politicians, was a member of the Canadian consortium, but an American group with stronger links to Washington and the new military government prevailed. The Canadians negotiated a merger with the Americans, and Van Horne became a director of the amalgamated undertaking. His financial commitment, however, was relatively small.

In January 1900 Van Horne paid his first visit to Cuba, where he quickly recognized a much more challenging opportunity: Cuba’s steam railways were in need of reorganization and there was no trunk line. His discovery that some railways had been built without charters on privately owned land such as plantations led to the conviction that he could circumvent the law on charters if he acquired land along the proposed trunk route and built pieces of a private line on each section. To make this assemblage possible, the Cuba Company was incorporated in 1900 in New Jersey, with Van Horne as president, and he and his associates together pledged $8 million. Van Horne then began to build, but not without problems. The railway had to cross municipal and provincial roads and it needed access to the business districts of towns and cities. When the necessary permissions or concessions were not forthcoming, Van Horne simply stopped construction, throwing thousands of labourers out of work, and threatened to by-pass the centres. The resulting political pressure, combined with Van Horne’s cordial demeanour, invariably produced the required support. Federally owned lands and roads posed greater difficulty since the charter law did not allow the military governor to grant concessions to use or cross such property. Van Horne suggested the brilliant expedient of a revocable permit, under which the railway could build but permission could be revoked when a civilian government took power. No action would ever be likely, however, if the railway maintained good relations with the public and communities derived economic gain.

In addition to the railway, the Cuba Company (renamed the Cuba Railroad Company in 1902) invested in developments designed both to benefit the populace and to generate needed traffic. Large tracts were acquired and opened to settlement under a colonization program devised by Van Horne. In a pattern of development similar to that established for the CPR, sugar mills and plantations, hotels, harbour and wharf facilities, town-sites, and mining and lumbering operations were also acquired or built. One entirely new port, Antilla, was developed in partnership with the United Fruit Company. In Camagüey, where the Cuba Railroad Company had its headquarters and a grand station, former barracks were converted into a luxurious resort, the Hotel Camagüey. Nearby Van Horne established his own hacienda and a large experimental farm, following the example of the 7,000-acre, stock-breeding farm he had set up in East Selkirk, Man. The support given locally to the projects of the Cuba Railroad Company stood in sharp contrast to the hostility elicited by other Latin American ventures with which Van Horne was involved. The electric tramways of Havana, for example, were disliked and Van Horne tried to hide his involvement. When offered the presidency of the Havana Electric Tramway Company, he refused because he feared that it might undermine goodwill toward the Cuba Railroad Company. He nevertheless remained a shareholder and sometimes a “silent managing partner” in numerous unpopular and exploitative ventures.

Although in North America Van Horne was most devoted to the CPR, he participated and invested in a host of other enterprises. Some companies, notably Canadian Salt, Laurentide Paper, Dominion Iron and Steel, Dominion Steel, North West Land, Equitable Life Assurance, Royal Trust, and a number of western flour-milling and elevator companies, became quite profitable; other interests, including a sardine-packing plant, a powder factory, and several gold-mining ventures, were failures. Over the years Van Horne was a director of at least 40 companies and he invested in many more. These investments, along with the CPR and his Cuban interests, made him an exceptionally wealthy man and one of Canada’s most prominent capitalists. Despite his weak complaints that his purse could not match the resources of some of his CPR associates, Van Horne enjoyed his luxuries, including drink and cards (he could outlast his contemporaries at both). The most visible marks of his affluence were his massive home on Rue Sherbrooke in Montreal; his Cuban estate and Covenhoven, his summer home on Ministers Island, N.B.; and his substantial collection of art. There was, indeed, a refined side to his swaggering railway persona.

A knowledgeable collector of fossils in his youth, Van Horne, after his move to Montreal, began to acquire art in a serious way, as did other CPR builders and financiers. His collection of old Dutch and Flemish masters and important French, English, Spanish, and American painters, which some critics regarded as one of the best in Canada, was assembled in an eclectic manner. He refused to buy any work, no matter how famous or inexpensive, if he did not find it satisfying. His treasures also included one of the best collections in North America of ancient Asian (particularly Japanese) porcelain and pottery. He became an expert on firing and the finish of his specimens, and he laboured for years compiling and illustrating a catalogue of these works, a sizeable portion of which he gave to the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto. This interest, together with his efforts as president of the CPR to promote increased trade with Japan, earned him a special invitation to visit as a guest of the emperor.

William Van Horne was not only a collector but also an artist in his own right. An excellent violinist who enjoyed playing classical pieces, he is better remembered for his painting. As a child, when he saw a geological textbook that he could not afford, he copied it, illustrations and all. His skill at caricature, which had ended his formal education, found later expression in the sketches of technical and descriptive details that accompanied much of his correspondence. He seemed to have a photographic memory and cherished spontaneity, which he did not believe could be taught in art schools: he usually painted quickly, at night, in a studio in his Montreal mansion. (The artificial lighting sometimes seems to have produced distorted tones in his work.) Although he had ability, critics suggested that his paintings “do not at all adequately express his efficiency or powers, simply because they were too hasty.”

Van Horne, like many of those associated with him in Canadian railways, contributed generously to hospitals, art galleries, and public parks. As well, he made more modest donations to a few military and educational causes. Also like his fellow railwaymen, Van Horne was suspicious of most forms of charity. He was willing to invest, and lose, large sums in the development of model farms which would promote better farming methods in western Canada or Cuba, but he did not usually assist the urban mission work done by men such as James Shaver Woodsworth*, believing it to be demoralizing in effect and destructive of independence of character. Only the immediate relief of clear cases of distress elicited any support from him.

Van Horne also tried, generally, to avoid involvement in partisan politics, even though railways and other work brought him into frequent contact with political figures. His assessments of politicians were often critical, but he had a high regard for their craft, whether in the form of function, influence, or humbug, and he clearly understood the importance for the CPR of political affiliation. The CPR had been viewed by the Liberals as a Conservative corporation since its creation, and its strong intervention in the federal election of 1891 bolstered this belief. Subsequently, Van Horne attempted discreetly to align his company with the Liberals, and he channelled his efforts through two leading Ontario Liberals in particular, party organizer and mp James David Edgar* and journalist John Stephen Willison*. Some months before the election of 1896, Edgar told Willison that Van Horne “believes firmly that we are going to win, and he does not lack ability to draw a few conclusions.” Almost immediately after the election, which brought Laurier to power, the Crowsnest negotiations began.

On only two important occasions did Van Horne engage in direct partisan combat. The first had come in the late stages of building the CPR main line, when syndicate members and company officials besieged Ottawa with desperate demands for financial assistance. The second occurred in 1911 when the Laurier government negotiated a reciprocity agreement with the United States. Van Horne believed that industries which had grown up behind the protective National Policy were threatened by reciprocity, and he campaigned aggressively “to bust the damn thing.” He was not, however, a doctrinaire protectionist. At other times he strongly supported free trade measures, particularly those that would reduce American tariffs against Cuban sugar.

In late 1913 Van Horne experienced his first “definite illness” in the form of an attack of rheumatism. Humiliated by this condition, he fought it, but by early 1914 he was forced to learn to use crutches. In 1915, during World War I, he was selected by Prime Minister Sir Robert Laird Borden* to head a commission on resources, but Van Horne’s death on 11 September intervened. A Unitarian funeral service was held at his Montreal home and a special CPR train took his body back to Joliet for burial in Oakwood Cemetery.

Sir William C. Van Horne liked big things: the largest and best locomotives, the biggest salary earned by a North American railway executive, generous (sometimes double) meals, big Cuban cigars, the massive Camagüey hotel, the huge gardens and broad roof of his beloved Covenhoven, the unusually large rooms and high ceilings of his Montreal home, the size of many of his own paintings and most cherished works of art, the grandeur of the Rocky Mountains and the CPR’s hotels, his visions of world-wide systems of commercial transportation and trading, and the greatness of the British empire. This passion for bigness, complemented by a usually keen eye for detail, was matched by exceptional energy, vision, and enthusiasm which made it possible for Van Horne to achieve or obtain many of the great things he so prized. His interests were numerous and varied, but construction of the CPR was his greatest contribution to Canada. As a railwayman, he had many rivals. Others were more successful as financiers, promoters, and lobbyists, but none equalled his achievement in the building and operation of integrated systems of railway transportation and economic development, first in Canada and later in Cuba.

Much of the material presented here is drawn from the Van Horne papers (MG 29, A60) and the Canadian Pacific Railway papers (MG 28, III 20) at the NA, and from the Canadian Pacific Arch., Montreal. The major secondary sources follow.

Pierre Berton, The last spike: the great railway, 1881–1885 (Toronto and Montreal, 1971). E. A. Collard, Montreal yesterdays (Toronto, 1962), 249–61. David Cruise and Alison Griffiths, Lords of the line (Markham, Ont., 1988). J. A. Eagle, The Canadian Pacific Railway and the development of western Canada, 1896–1914 (Kingston, Ont., 1989). W. K. Lamb, History of the Canadian Pacific Railway (New York and London, 1977). O. [–S.–A.] Lavallée, Van Horne’s road: an illustrated account of the construction and first years of operation of the Canadian Pacific transcontinental railway (Montreal, 1974). S. Macnaughtan, “Sir William Van Horne,” Cornhill Magazine (London), new ser., 40 (January-June 1916): 237–50. Allan Pringle, “William Cornelius Van Horne, art director, Canadian Pacific Railway,” Journal of Canadian Art Hist. (Montreal), 8 (1984): 50–78. Gonzalo de Quegada, “The iron horse in east Cuba,” Gulf Stream (Havana, Cuba), [1 ] (1929), no.3. “Railways in Cuba: the completed trunk line of the Cuba Company from Santa Clara to Santiago de Cuba and branches,” Railway Age (Chicago), 9 Jan. 1903. C. L. Sibley, “Van Horne and his Cuban railway,” Canadian Magazine, 41 (May-October 1913): 444–51. Walter Vaughan, The life and work of Sir William Van Horne (New York, 1920). W. R. Watson, Retrospective: recollections of a Montreal art dealer (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 1974).

Cite This Article

Theodore D. Regehr, “VAN HORNE, Sir WILLIAM CORNELIUS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 31, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/van_horne_william_cornelius_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/van_horne_william_cornelius_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Theodore D. Regehr |

| Title of Article: | VAN HORNE, Sir WILLIAM CORNELIUS |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | January 31, 2026 |