GARNEAU, FRANÇOIS-XAVIER, notary, poet, and historian; b. 15 June 1809 at Quebec, son of François-Xavier Garneau and Gertrude Amiot-Villeneuve; m. on 25 Aug. 1835, at Quebec, Marie-Esther Bilodeau, and they had ten children; d. during the night of 2–3 Feb. 1866 in his native town.

François-Xavier Garneau’s ancestor, Louis Garnault, came originally from Poitou, landed at Quebec around 1659, and settled at L’Ange-Gardien, on the Beaupré shore. His descendants made their home at Saint-Augustin, west of Quebec, but the historian’s father went to live in the faubourg Saint-Jean at Quebec (now the parish of Saint-Jean-Baptiste). At the beginning of the 19th century Quebec had 8,000 inhabitants, the majority of whom were French speaking. It was the seat of the government of Lower Canada and of both Catholic and Anglican dioceses. The English speaking group (English, Scottish, Irish), who held positions in the government, the garrison, and the world of trade and industry, constituted an important segment of the population of this town, where architecture, habits, and customs all served as reminders that Quebec had been the capital of New France.

François-Xavier’s father, with neither wealth nor a profession, met the needs of his growing family by being in turn a saddler, a carter, the captain of a merchant schooner, and finally an innkeeper. There were three children born after François-Xavier: David, who became a businessman at Quebec, Honoré, who enlisted in the American army at the time of the war against Mexico, and Marie-Émélie, who married Charles Routier of Quebec.

Young Garneau, whose lively mind apparently attracted attention quite early, was put in the local school, which was run by an aged teacher known as “le bonhomme Parent.” Tradition has it that he was a serious and brilliant pupil. One of the earliest memories Garneau recounted concerns his fondness for history. In his Voyage en Angleterre et en France . . . , published in 1855, he recalled that his grandfather Jacques Garneau of Saint-Augustin liked telling him the story of the naval battle he had witnessed in 1760 between the Atalante, commanded by Jean Vauquelin*, and two English frigates.

In 1821, when Garneau was 12 years old, he had absorbed all the knowledge that “le bonhomme Parent” could offer. That year he entered a school which had been opened in the basement of the chapel of the Congrégation des Hommes de la Haute Ville through the efforts of Joseph-François Perrault*. Garneau spent two years here in what was called a “mutual” school, in which teaching was conducted according to the method of English educator Joseph Lancaster, the most advanced pupils being used as instructors. Garneau became an instructor, and his diligence brought him to Perrault’s attention. When he left the school, Garneau wanted to enter the Séminaire de Québec, the only college in the district where boys could get a normal classical education. His parents lacked the means to provide for their child’s education and the seminary was reluctant to assist the young pupil who felt no attraction to holy orders. Garneau had therefore to abandon the hope of studying humanities. Perrault, who was clerk of the Court of King’s Bench and his patron, offered him a job in his office. For two years the young man benefited from the experience and culture of the clerk, in whose house he sometimes spent his evenings. Perrault, an old man who had read and travelled widely and who belonged to a family active in the army and administration of New France, gave Garneau and his clerks English, Latin, and history lessons, and placed his library at their disposal.

In 1825 Garneau chose the profession of notary. He was introduced to Archibald Campbell, a notary in charge of the most respected office in the town of Quebec. Young Québecois, such as Pierre Petitclair*, a poet and dramatist, and Antoine-Sébastien Falardeau*, the future painter, also served their apprenticeship there. On 22 June Campbell and Garneau signed the indentures covering the latter’s legal training: the notary undertook to teach the practices of his profession and to pay the young clerk £13 a year for the next five years. Garneau devoted himself to his work and took advantage of his leisure to delve into his master’s library, which contained a good collection of English, Latin, and French classical works. In this way he continued to teach himself Latin, which he had begun to study under Perrault, and he eventually was able to read Horace at sight. He also learned Italian on his own, and improved his English by reading Byron, Milton, and Shakespeare.

At the end of August 1828 Garneau set off on a journey with an Englishman who had asked Campbell to recommend a companion whose expenses he would pay. The travellers went to Saint John, New Brunswick, proceeded to Boston by boat, then went to New York. Garneau spent some 20 days visiting the great American city. From New York they went via Albany and Rochester to Buffalo, then travelled overland to Niagara Falls. They finally returned to Quebec by way of Queenston, York (Toronto), and Kingston. Later, in his Voyage, Garneau recalled this long trip, which allowed him to see the United States and Upper Canada for himself.

After five years of legal training, Garneau took his examination on 23 June 1830 and received his commission as a notary; however, he took a year of further training. During this period Garneau began to try his hand at poetry: on 31 Aug. 1831, displaying a certain indulgence, Le Canadien of Quebec published a topical poem entitled “Dithyrambe: Sur la mission de Mr Viger, envoyé des Canadiens en Angleterre.”

By his own testimony, Garneau had long been dreaming of visiting the old world, the “cradle of genius and civilization.” On 20 June 1831, with his modest savings in his pocket, he sailed for London. He reached his destination a month later, and devoted most of his time to visiting and studying the English capital. On 26 July he set out for France, anxious to know the country of his ancestors. Two days later he arrived in Paris, in the midst of the celebrations marking the anniversary of the July revolution: the young man was delighted to see France resolutely committed to liberalism. He immediately set out to explore the Ville lumière; he spent several evenings at the theatre, and during the day visited museums and libraries. He also went to see Isidore-Frédéric-Thomas Lebrun, the scholar.

On 9 Aug. 1831 Garneau returned to London. Montreal mha Denis-Benjamin Viger, who had been sent by the House of Assembly to make numerous representations to the Colonial Office, including a request that Attorney General James Stuart* be dismissed, suggested that Garneau become his secretary. Garneau had expected to return home in the autumn but changed his plans and accepted the offer. Thus for a year he copied reports for Viger. At the same time he learned something about Canadian and British policy. His correspondence shows he was highly critical of the colonial régime and the institutions introduced into Lower Canada by Great Britain. While Viger lodged at the luxurious London Coffee House, Garneau lived in a boarding house on Cecil Street, near Charing Cross, where another gifted young mha, Joseph-Isidore Bédard*, son of Pierre-Stanislas Bédard*, also lived. The delegate from the Lower Canadian assembly entertained a great deal, which gave the young secretary an opportunity to meet and hear some of the great figures of Canadian and British politics, such as William Lyon Mackenzie, the Upper Canadian Reformer, John Arthur Roebuck*, a member of the British parliament and an ally of French Canadians, and John MacGregor*, a publicist and statistician who was to gain public attention by his writings about Canada. Garneau also met the Irish patriot Daniel O’Connell and was impressed by his gifts as a speaker. During his free time the young secretary attended concerts, went to the theatre, and was an interested observer of popular meetings and parliamentary debates during the period of electoral reform in 1832.

Since 1830 many refugees had flocked to London. Garneau had occasion to meet the Poles who had chosen exile after the tragic dénouement of the Warsaw insurrection in 1831. He struck up a friendship with Dr Krystyn Lach-Szyrma, at whose house he met several Polish refugees. Many liberal-minded members of the House of Commons were well disposed towards the Polish cause, and supported the principles of the new Literary Society of the Friends of Poland, of which the poet Thomas Campbell was president. Elected to the society on 15 Aug. 1832, Garneau presented a specially composed poem, “La liberté prophétisant sur l’avenir de la Pologne,” in which he recounted the history of a country divided and sorely tried by the bloody events of the years 1830 and 1831.

At the end of the summer of 1832 Garneau had the opportunity to undertake a second trip to Paris, this time with Viger and MacGregor. The trip, which deepened his knowledge of France, lasted from 15 September to 3 October. In Paris Garneau again saw Lebrun, who was working on a book on Canada: thus began an exchange of views which went on for some years. He also met Amable Berthelot*, a lawyer and scholar from Quebec who later became his benefactor. The winter of 1832–33 was for Garneau as studious as the preceding one. Compatriots visiting London brought news of the bloody riot at Montreal during the elections of May 1832. At the end of the winter Garneau decided to return home. His father had died on 7 Aug. 1831, and his mother was in poor health.

After his return to Quebec on 30 June 1833, Garneau seems to have been hesitant about his future. Although this period of his life is less well known, it is clear Garneau was writing poetry. From 19 July to 18 October Le Canadien published at least six of his poems, including “Souvenir d’un Polonais,” which seems to be a poem of recollections addressed to his friend Lach-Szyrma, “Le Canadien en France,” an elegy composed in Europe, and “La Coupe.” Only the last piece, composed in July 1830, is dated. Garneau thought of becoming a journalist, a difficult means of earning a livelihood at the time. On 7 Dec. 1833 the first number of the paper L’Abeille canadienne, founded and edited by Garneau, and printed by Jean-Baptiste Fréchette, was published at Quebec. The paper proposed to encourage “the spread of knowledge and a liking for reading.” It was an unpretentious weekly, and ceased publication two months later, on 8 Feb. 1834, without attaining the longevity of papers such as the Penny Magazine of London, or the Magasin pittoresque of Paris, which Garneau had wanted to imitate in order to further popular education.

In February 1834 Garneau, with no marked enthusiasm, began to work as a notary in the office of Louis-Théodore Besserer, with whom he had gone into partnership in the summer of 1833. In the whole of 1834 he wrote only two poems, “Le Premier Jour de l’an, 1834,” and “Chanson Québec,” which Le Canadien, as always, loyally published. Politics already seemed to be preoccupying his leisure. He followed closely the conflict, then reaching its peak, between the House of Assembly, dominated by French Canadians, and the Legislative Council and the executive. Elzéar Bédard*, Augustin-Norbert Morin, and Louis-Joseph Papineau* had taken the lead by presenting the 92 Resolutions in the assembly. Garneau assisted Étienne Parent*, the guiding spirit of the revived Le Canadien, which vehemently defended French Canadian nationality. In March 1834 Garneau became secretary of the constitutional committee, and thus laid himself open to attack by the Quebec Gazette, a resolute supporter of the status quo.

In May 1836, less than a year after his marriage, Garneau parted company with Besserer, and opened his own office on the Côte de la Montagne; but he does not seem to have been happy in the performance of his duties. In 1837 he became cashier in the Bank of British North America, and two years later an employee of the Quebec Bank. He continued to practise as a notary on occasion, and drafted a dozen acts a year between 1837 and 1842.

Garneau’s political activity in the years 1837 to 1840 is little known. Although his contemporaries did not comment on it and his correspondence for this period has not been discovered, his poems and his interpretation of events in Histoire du Canada depuis sa découverte jusqu’à nos jours (published in 1845) enable us to affirm that on the whole he favoured Papineau’s ideas.

It is during 1837 that the first clear signs of Garneau’s vocation as an historian can be detected. In Le Canadien of 15 February he published an historical piece on the combats and battles “waged in Canada and elsewhere in which Canadiens have taken part.” His first writing of this kind, it emerged from the same patriotic inspiration as his poems. True, in 1832 in London, he had copied a French officer’s diary of the siege of Quebec at his employer’s request, and Viger had published this document in 1836, but we cannot argue from this fact that Garneau had decided to write the history of his country during his stay in England. In 1837 history was of interest to an increasingly wide public which, like Garneau himself, wanted to understand the present and find reasons for hope in a past which they believed to be glorious, but which had been recounted by Anglo-Saxons such as Robert Christie*, William Smith*, and John MacGregor with their compatriots in mind. Moreover, the works published in French could not satisfy the new generation of Patriotes. In 1833 Lebrun had published in France a Tableau statistique et politique des deux Canadas, which despite its abundant detail was lacking in subtlety of perception. Since 1819 Michel Bibaud* had been writing well-documented historical articles, but these supported the status quo, and therefore alienated some readers. Jacques Viger*, Amable Berthelot, and Jacques Labrie* were reasonably competent antiquaries with limited historical vision. Most recently, between 1831 and 1836 Joseph-François Perrault had published an Abrégé de l’histoire du Canada in five volumes which was a worthwhile attempt at popularization but dull and confused.

Although Garneau took a serious interest in history from 1837 on, it was the union of the Canadas, a measure endangering the survival of the French Canadian nation, that unquestionably confirmed his vocation as an historian and prompted his determination to write a history of Canada. By so doing, Garneau sought to revive the courage of fellow citizens who experienced misgivings and doubts; he proposed to arouse their will to live, and he wanted to combat the British contempt for the “Canadiens.” On 24 Jan. 1840 he signed and circulated a resolution against the Act of Union, which was adopted at a protest meeting attended by Étienne Parent, John Neilson*, and Louis-Édouard Glackmeyer*. Nevertheless the Act of Union was passed, and its application roused indignation. On 22 Feb. 1841, in a long article in Le Canadien, Garneau again attacked the imperial enactment, and demanded the maintenance of the French language, which was no longer constitutionally guaranteed.

Garneau, however, continued to try to develop his compatriots’ liking for literature. With Louis-David Roy*, he launched a semi-literary, semi-scientific weekly, L’Institut, ou Journal des étudians, first published on 7 March 1841. In the autumn of 1840 a resourceful Frenchman, Nicolas-Marie-Alexandre Vattemare, had come to Canada as the “guest” of Denis-Benjamin Viger, bringing with him a book exchange plan that had the warm support of the civil and religious authorities and of prominent citizens. At Quebec, Le Canadien, Napoléon Aubin*’s Le Fantasque, and L’Institut, ou Journal des étudians welcomed his proposal enthusiastically. On 13 March 1841 Garneau’s paper reported the formation of a general committee, chaired by John Neilson, whose object was to found an institute as inspired by Vattemare, a sort of federation of the cultural societies in the town of Quebec, to foster wider diffusion of knowledge and bring “classes” and “races” closer together. But Vattemare’s plan was short-lived. It clashed with the interests of the societies – the Literary and Historical Society of Quebec for example – who were jealous of their autonomy. Furthermore, the project came at a bad political juncture (the union of the Canadas had been proclaimed on 10 Feb. 1841), and it remained only a plan. Yet the foundation in 1847 of the Institut Canadien of Quebec, of which Garneau became a mainstay, can be partly explained by the enthusiasm aroused by Vattemare’s projects. After the latter left Canada the two men kept up a correspondence for a long time.

In September 1842, through the good offices of his friend Parent, Garneau obtained the post of French translator to the Legislative Assembly. This position left him free time for reading, and gave him easy access to the valuable library assembled by Georges-Barthélemi Faribault. As a member of the Literary and Historical Society of Quebec, he could also draw upon the rich collection of this association, which had been founded in 1824. In June 1843 Garneau sent Le Canadien an article on the voyages of Jacques Cartier*, a prelude to his full-scale historical work. Although he was absorbed by his Histoire du Canada, which had become the great passion of his life, Garneau nevertheless kept in close contact with political and national life. In 1842 he helped found the Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste at Quebec [see Pierre-Martial Bardy]. He was opposed to the autocratic policy of Governor General Lord Sydenham [Thomson*], but was later well disposed towards Sir Charles Bagot*, who looked favourably upon the French population; it was Garneau who drafted the appropriate address on Bagot’s departure in March 1843. In January 1844 Garneau and others petitioned for the return of the political exiles who had left the country in 1837. That year, with the help of Louis-Édouard Glackmeyer, he obtained the post of clerk of the city of Quebec, which meant an increased salary but less leisure time, and riveted him to a task which he scarcely found appealing. From 1835 to 1845 Garneau published 14 poems, including “Au Canada,” “A lord Durham,” “L’Hiver,” “Le Dernier Huron,” “Les Exilés,” and “Le Vieux Chêne.” His best pieces, “Le Dernier Huron” and “Le Vieux Chêne,” are imbued with patriotic feeling, and point to his Histoire du Canada.

In August 1845 the first volume of Garneau’s Histoire was published at Quebec. The work is preceded by a “Discours préliminaire,” in which the author recalls the development of historical criticism in the west since the Renaissance and outlines his ideas concerning the philosophy of history; it is divided into five books and 16 chapters; it begins with two introductory chapters on the discoveries and explorations of the late 16th century. The volume describes events in New France from its beginnings until 1701, when peace was concluded with the Indian tribes. The best pages are those dealing with the work of Samuel de Champlain*, Bishop François de Laval*, the wars between Hurons and Iroquois, the new machinery of government in 1663, and the state of the English colonies in 1690; in analysing these colonies he offers an interesting parallel with New France, one that has become famous.

The book seems to have been well received at first. But soon after its publication, the papers published letters and reviews which judged the Histoire du Canada severely. Anonymous authors, frequently clergymen, reproached Garneau for his defence of freedom of conscience, his regrets that French authorities had excluded the Huguenots from Canada, and especially his criticisms of Bishop Laval’s authoritarianism. Doubts were frequently cast on the religious convictions and the nationalism of the writer, who was called a “philosopher,” a “Protestant,” and an “ungodly” man. Garneau seems to have been deeply mortified by this display of hostility.

At the time the first volume of the Histoire du Canada was published, Garneau went to Albany, where the archives of New York State were located, to consult their collections of copies of official documents held in the French national archives. Here he again met his friend Edmund Bailey O’Callaghan*, a Patriote who had taken refuge in the United States in 1837 and become the state archivist. This new source of documentation provided fuller material for the second volume of the Histoire du Canada, which was published in April 1846. The narrative covers the period from 1683 to 1775. Garneau first recalls the fate of Louisiana and that of Acadia, then discusses trade from 1608 to 1744, before reconstructing in detail the war of the Conquest. The brilliant French victories are recounted with spirit, France’s neglect of her colony is denounced, François Bigot* and his clique are held up to shame. The last book of the second volume discusses the early years of the British régime, beginning with the military era which Garneau regarded as odious, and ending with the Quebec Act, or more precisely with the first difficulties with the rebellious American colonies. This second volume, which seldom deals with ecclesiastical questions, does not seem to have caused the impassioned controversies that followed publication of the first. And from Paris Garneau received unexpected support. In 1847 Lebrun published in the Nouvelle Revue encyclopédique a laudatory review of the Histoire du Canada, which several Quebec papers, including Le Canadien, hastened to reprint.

In 1846 Garneau went to Montreal to examine the four volumes of documents and reports on New France that Louis-Joseph Papineau had had copied in Paris at the request of the government of United Canada. However, the heavy work he undertook affected his health. At the beginning of 1847 he had an epileptic seizure (he had suffered from epilepsy since 1843), complicated by attacks of typhoid and erysipelas, which prevented him from continuing his work at the rate he had anticipated.

In 1848, 19 poems Garneau had written between 1832 and 1841 were published in James Huston*’s Le répertoire national, ou recueil de littérature canadienne. His growing reputation as an historian heightened his renown as a poet. The year 1848 was printed as the publication date of the third volume of the Histoire du Canada, relating events from 1775 to 1792, but the work did not in fact come out until March 1849. Local critics, according to Garneau, seemed to have nothing to say. Garneau’s reputation as an historian now appeared solidly established. His proclamation in the third volume that religion and nationality were united had disarmed the clerical critics, as Garneau stressed in May 1850 in a letter to O’Callaghan. As a token of goodwill the archbishop of Quebec, Joseph Signay*, opened the episcopal archives to him. In May 1849 the legislature granted Garneau $1,000 for a new edition of the Histoire du Canada. The author already had in mind considerable improvements in both content and style. Severe and exacting, Garneau sought perfection, correcting, shaping, and completing his text.

Distinguished travellers passing through Quebec paid calls upon the historian. Two Frenchmen, Xavier Marmier who came in 1849 and Jean-Jacques Ampère in 1851, described their pleasant memories of time spent in the company of a “cicerone” as learned as he was patriotic. François-Edmé Rameau de Saint-Père, who also met Garneau, continued an interesting correspondence with him. The most spectacular visit was that of Paul-Henry de Belvèze*, the commander of La Capricieuse, which called at Quebec in 1855; the French officer, to whom Garneau had presented a copy of the Histoire du Canada, asked that the author be introduced to him, and saluted him as “the national historian of Canada.”

The narrative of the first edition of the Histoire du Canada (totalling more than 1,600 pages) had scarcely gone beyond the year 1792. Resuming his work, Garneau proceeded with an account of historical events up to 1840, and also obtained more sources for the purpose of the second edition. He was able to draw on several useful sources: to the documents in the archdiocesan archives at Quebec, and those at Albany, was now added the official correspondence of the English governors of Canada up to the period of Lord Dalhousie [Ramsay*], which was placed at his disposal by the governor Lord Elgin [Bruce] as a sign of his esteem. In the autumn of 1852 the second edition of the Histoire du Canada was published in three volumes. Garneau had made countless stylistic emendations and expanded the documentation of this work. He had also provided an account of events from 1792 to 1840, stressing the constitutional struggles. This addition was published in instalments intended as a supplement for the subscribers to the first edition. After the description of the reign “of terror” of Sir James Henry Craig* and of the War of 1812, Garneau gave particular attention to the struggle between the Patriote leaders and the English oligarchy surrounding the governors. England’s policy, after raising a few hopes, proved hostile to the Canadian Patriotes. The disturbances of 1837 and 1838 broke out and were harshly put down. The union of the two Canadas proved to be a catastrophe for French Canada, according to Garneau. In his general conclusion he urged French Canadians to remain true to themselves by refraining from political and social ventures.

The Histoire du Canada continued to meet with success and attracted wider critical attention. Theodore Pavie, a literary critic from Anjou who had travelled in North America in his youth, gave a favourable account in the 15 July 1853 number of the celebrated Revue des deux mondes of Paris. In Le Correspondant (Paris) of 25 Dec. 1853 another Frenchman, Louis-Ignace Moreau, analysed the work at length and censured it in terms reminiscent of the ecclesiastical criticisms stimulated by the publication of the first volume of the first edition. In Boston, Orestes Augustus Brownson, who was then a liberal Catholic, praised the Histoire du Canada eloquently in the October 1853 issue of Brownson’s Quarterly Review.

Yielding, as he said, to the persuasion of friends, Garneau published his recollections of travel in England and France in Le Journal de Quebec, from 18 Nov. 1854 to 29 May 1855. The text started as travel notes, then took the form of a diary, which was expanded through his later readings. In the spring of 1855 he brought his material together in a volume entitled Voyage en Angleterre et en France dans les années 1831, 1832 et 1833, which was published by Augustin Côté*. Once the volume was in print, Garneau distributed ten copies to his friends, and immediately received crushing comments; he was criticized for lapses in style and his republican ideas were deplored; certain passages directed against former Patriote leaders, who supported the government under the union, such as Augustin-Norbert Morin (who however was not named), provoked reservations and displeasure. Hesitant and embittered, Garneau asked his publisher to destroy the copies not yet distributed, and only a few volumes were saved. The Voyage remains a document of prime importance for understanding Garneau’s formative years.

In 1855, at the time his Voyage was printed, Garneau was severely taken to task by the son of historian Michel Bibaud, François-Marie-Uncas-Maximilien Bibaud*. In a bitter pamphlet entitled Revue critique de l’ “Histoire du Canada” de M. Garneau, Bibaud took pleasure in pointing out the incorrect phrasing as well as the errors of date and the contradictions scattered throughout the work of this self-taught man. Bibaud, who spoke of “charlatanism in history,” was displeased with the book’s general ideology, which was the direct opposite of the one animating the Histoire du Canada, et des Canadiens, sous la domination anglaise (Montréal, 1844) by his father, which was hostile to the Patriotes. Bibaud’s exaggerated statements came too late, however, to undermine seriously Garneau’s high reputation.

On the occasion of a competition launched by the editor and printer Côté in 1856, Garneau wrote an Abrégé de l’histoire du Canada depuis sa découverte jusqu’à 1840, à l’usage des maisons d’éducation. It was a dull little book, in the form of questions and answers, from which the historian took care to eliminate anything that might offend the clergy. Fortified by the imprimatur of the archbishop of Quebec, the manual enjoyed considerable success. In his biography of Garneau, Pierre-Joseph-Olivier Chauveau* recalls that by 1882 the book had sold 30,000 copies. Garneau wrote it without enthusiasm, as if it were a lengthy punishment inflicted on a schoolboy, and without paying much attention to Chauveau’s suggestions that he should make it more attractive and better suited to young readers.

Meanwhile Garneau was preparing a third edition of Histoire du Canada with the help of his son Alfred. Since the publication of the second edition the historian had gained access to yet more primary sources. Georges-Barthélemi Faribault, who had succeeded in interesting the Canadian government in keeping archives, had had numerous documents copied, and these were available to researchers from the autumn of 1853. In addition, Abbé Jean-Baptiste-Antoine Ferland had brought back from France a large number of documents to which Garneau had partial access. He also used the fifth and sixth volumes of the History of the late province of Lower Canada . . . by Robert Christie, which had been written in a very different spirit from his own. Garneau the perfectionist re-examined his entire Histoire du Canada for the new edition: not a page escaped correction, a substantial number of additions and changes were made, the narrative was filled out by new documents, and the style was carefully revised and polished. In 1859 the third edition, the last in Garneau’s lifetime, was published. It ensured him the title of “national historian.” Tirelessly he set to work on a fourth edition, which his son Alfred was to bring to completion in 1882 and 1883. But his health was daily becoming more delicate. Garneau had been a member of the Council of Public Instruction since its formation in 1859, but found himself obliged to give up his office in May 1862. In 1864 illness forced him to resign as clerk of Quebec.

The Histoire du Canada had continued to be well received. French historian Henri Martin quoted Garneau approvingly. The Institut Canadien of Quebec made him its honorary president. A Briton who had settled in Canada, Andrew Bell, translated the Histoire, at the same time adapting it somewhat freely for the Anglo-Saxon public. The historian protested vigorously against the undertaking, which in his opinion distorted his work. Despite these reservations, Bell’s translation, published in 1860, was a definite success, and was re-issued in 1862. In our day the English speaking public still knows Garneau’s work through Bell’s translation.

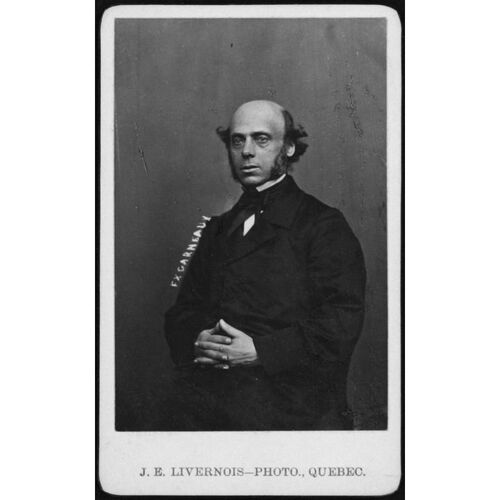

There are no documents to provide the means for sketching a portrait of Garneau. He was reserved in nature and lived a quiet life. Those close to him have left us little to go on. His correspondence was voluminous, according to Abbé Henri-Raymond Casgrain* and Chauveau, but only some hundred letters remain. What is known about Garneau comes principally from three of his contemporaries, notary Louis-Michel Darveau*, Chauveau, and Casgrain, whose descriptions written after his death show contradictions and also some idealization. Below medium height, and with a high forehead, Garneau had a meditative appearance. Timid, seemingly even gentle and conciliatory, he was yet firm and “almost obdurate” in certain matters. He showed a nervous hesitation, an embarrassment probably linked to the progress of the disease he had suffered from since 1843. He was most at ease in small, intimate gatherings. His diligence in work was legendary. A self-taught man in a world where the influential almost all received a classical education, Garneau seemed sensitive to the point of touchiness. This characteristic helps explain his concern to revise his work constantly, and his intractability in the defence of his ideas.

Those ideas are known primarily through his Voyage and his Histoire du Canada, though his poems and his correspondence are valuable. In Europe he admired the France of 1830 and even more England, which was evolving towards increasing political liberty. Did he occasionally feel drawn to republican institutions? Certain pages on the United States and France seem to suggest that he did. In the religious sphere he supported the distinction between the spiritual and political in a period when ultramontanism was spreading: hence the accusations of Gallicanism and liberalism levelled against him even well into the 20th century. Casgrain and Chauveau conjure up for us a fundamentally religious Garneau, but his son Alfred recounts the “conversion” of his “Voltairian” father on his death bed. In his work Garneau showed little interest in religion itself, but rather dealt with the relations of the two powers, church and state. Above all, Garneau was concerned about his nationality: His life and work were marked by constant preoccupation with defending the right to survival of his compatriots, “the Canadiens,” who were threatened by “the Anglo-Saxon race.” With time, Garneau’s thinking moved towards the consensus that circumstances imposed on his era. The famous, oft-repeated conclusion he published in 1848, advising his compatriots to shun ventures fraught with danger for a small nationality, reveals the distance his thought had travelled over a ten-year period.

Garneau was intellectually a self-made man. From his parents, who had had no education, he could receive no more than encouragement. His literary culture, vision of the world, ideas on man and on his country, even his principles and methods as an historian, Garneau owed to a thirst for knowledge and great industry. It seems likely Garneau acquired much of his knowledge from extensive and varied reading. In literature, he had read the classicists, the encyclopaedists, and the romantics; in history, he felt at home in contemporary historiography, particularly in the company of Augustin Thierry; he also did a great deal of general reading and examined Canadian and foreign newspapers. Garneau’s accomplishments were achieved with difficulty because of his straitened circumstances. It should be noted that to be able to continue his historical work, he had sought the help of his father-in-law and of city hall in Quebec, and the favours granted by parliament and by several friends. He brought up his family in an atmosphere saddened by frequent bereavements, for in the 20 years between 1835 and 1855 he fathered ten children of whom seven died in childhood.

As a writer Garneau was a poet, an historian, and a memorialist, a journalist on occasion, and a letter-writer when need arose. His manner of writing closely reflects his character and situation. His style is on the whole correct, and it is both terse and tentative. He strives for realism and clarity of expression, and his language demonstrates in its own way the weaknesses of a society still not well equipped with schools. Yet, despite unquestionable faults of vocabulary, grammar, and style, and the fact that he was entirely self-taught, Garneau redeems undeniable blunders in his writing by the vigour of the phrasing, by the narrative drive, and by the original vision of reality his words, clauses, and paragraphs convey. He was the first in Quebec to infuse poetry with romantic rhythm and colour; he was the first also to conceive the idea of a coherent and well-documented panorama of national history. As a writer Garneau was not given to elaborate detail, nor did he possess the brilliance of certain great authors; his skill lay in the inspiration that quickened his poems and in his dynamic style of narration. Garneau was aware that his work was not without flaws. That is why he continually reworked his material and still was never satisfied; he learned his art by writing, and was always conscious of his limitations.

A portrait of Garneau as a writer completes and in some ways confirms the portrait of the man. His poetry reveals his sensitivity and his vision of the world; the Histoire du Canada displays his learning as an historian and his ideas on the life of a nation; the Voyage gives his observations on London and Paris against the background of the two great ancient cultures. Garneau wrote laboriously, impelled by a vocation that slowly took shape, and above all by a sense of duty. As an artist he did not seek to dazzle; the writer was content to convince. As a creator he can be situated somewhere between the thinker who loved the age of enlightenment and the scholar who had reflected deeply on the art of the historian Thierry. He also had many romantic inclinations and a natural bent for meditation.

An attack of epilepsy, complicated by pleurisy, brought about Garneau’s death during the night of 2–3 Feb. 1866. The historian died in a house on Rue Saint-Flavien, in which, notwithstanding a persistent and widely held legend, he had lived only during the last years of his life. From 1854 to 1864 he had resided, first as a tenant then as owner, in a dwelling on Avenue Sainte-Geneviève.

The news of Garneau’s death was sent by the newspapers throughout French Canada, and his passing was felt as a bereavement by the whole nation. A committee was established to erect a monument and to assist his family. On 15 Sept. 1867, about a year and a half after his death, a memorial was unveiled in the Belmont cemetery, on the Sainte-Foy heights. On this occasion, Chauveau, in a moving homage to his late friend, made one of the finest speeches of his career. It is true that Garneau’s star had waned a little after the publication in the 1860s of Abbé Ferland’s Cours d’histoire du Canada, since its emphasis upon the religious dimension of the history of New France ensured its lasting success in Catholic and conservative French Canada. None the less, nobody disputes Garneau’s title as “national historian.” Another edition of his Histoire du Canada was the occasion for fresh praise and wider distribution. Early in the 20th century (1913–20), his grandson, Hector Garneau, published in Paris an updated version of the Histoire du Canada, based on the first edition. The reactions and comments it aroused once more testified to the importance of the Histoire in the French Canadian consciousness. Between 1944 and 1946 it was re-issued again – in the eighth edition – treated not so much as a classic text as a synthesis, brought up to date and unrivalled in its field. The centenary of the first edition was honoured in 1945 in impressive ceremonies at Montreal, Quebec, and Ottawa, and led to demonstrations in which patriotism vied with concern for historical knowledge.

Textbooks of literature and anthologies give a special place to Garneau, who is generally considered the greatest French Canadian author of the 19th century. Although since the 1950s historians have moved away from his primitive method of reconstructing the past, Garneau’s ideas still engender a good deal of interest today, and, reaching across generations, link up with the permanent aspirations of French speaking Canadians. The name of Garneau was given during his lifetime to a street in Quebec. Today, a college offering general and professional courses in the city of Quebec bears his name. Throughout French Canada, a considerable number of streets, parks, schools, lakes, and rivers, and a township, recall the memory of the man who wanted to give his compatriots reasons not to despair, and grounds for living to the full their destiny as Frenchmen in North America.

[From 1831 to 1841 Garneau published a number of poems in various newspapers, primarily Le Canadien. Nineteen of his poems were printed in Le répertoire national, ou recueil de littérature canadienne (Montréal, 1848), edited by James Huston. Garneau’s principal work, however, is Histoire du Canada depuis sa découverte jusqu’à nos jours (3v., Québec, 1845–48, et suppl., 1852). Two other editions (1852, and 3v., 1859) were published during his lifetime, and from 1859 until his death in 1866, Garneau was preparing, with the help of his son Alfred, a fourth edition (published in Montreal in 1882 and 1883). Three new editions were published in Paris, each in 2v., under the direction of Hector Garneau, the historian’s grandson (1913–20, 1920, 1928). Finally, an eighth edition, in 9 volumes, was prepared by Hector Garneau for the centenary of the Histoire’s first publication and was published in Montreal from 1944 to 1946. In 1860, Andrew Bell published a translation of Garneau’s work entitled History of Canada, from the time of its discovery till the union year (1840–1) (Montreal) which was republished in 1862, 1866, and 1876. Garneau is also the author of Voyage en Angleterre et en France dans les années 1831, 1832 et 1833 published in Quebec in 1855. This work was first printed in instalments in Le Journal de Québec from 18 Nov. 1854 to 29 May 1855. About two years before Garneau’s death an abridged version of his Voyage was published in La littérature canadienne de 1850 à 1860 (2v., Québec, 1863–64) and was reprinted in 1881. In 1968, Paul Wyczynski published an annotated critical edition of the original text of the Voyage. Finally in 1856 Garneau published Abrégé de l’histoire du Canada depuis sa découverte jusqu’à 1840, à l’usage des maisons d’éducation (Québec); new editions appeared in 1858, 1876, and 1881. Alfred Garneau and Pierre-Joseph-Olivier Chauveau prepared a section covering the period from 1840 to 1881 for the 1881 edition.

Sources of information for Garneau’s life are few, and virtually nothing is known of certain periods. The registers of births, marriages, and deaths and his notarial register, preserved at ANQ-Q, provide the essential facts. Only some hundred letters remain of what was a large correspondence, according to Henri-Raymond Casgrain in 1866; these letters are, however, full of information on the man and his work. Contemporary newspapers provide some of his writings (especially the poems) and some traces of his activity. The thousands of legal notices scattered through Quebec City newspapers between 1854 and 1864 are of little interest to the historian’s biographer. We have, of course, Garneau’s poetic and historical work and especially his account in his Voyage, which is rich in information about the man himself and the nature of his ideas.

Garneau’s first biographers could give personal accounts of his life. Abbé Casgrain published Un contemporain: F. X. Garneau (Québec) just after Garneau’s death. He knew the historian during his declining years; his portrait of him tries to conceal the disputes caused by Histoire du Canada in the years after 1845. Pierre-Joseph-Olivier Chauveau knew Garneau well, and traced the older man’s life for the fourth volume of the 1882–83 edition of Histoire du Canada. Despite several gaps attributable to his faulty memory, this biography is still the most complete. Chauveau’s own temperament and his concern to unite French Canadians led him to present a picture of Garneau that conforms to the nationalist ideal of the early 1880s which saw an optimistic future for French Canada under the protective wing of her leading citizens and the church. In his long analysis of Histoire du Canada, Chauveau concentrates on the most conciliatory statements of Garneau, and he praised French Canada’s recovery since 1850. The striking portrait that Chauveau drew of Garneau’s physical and mental qualities has often been repeated in anthologies. In Nos hommes de lettres, published in Montreal in 1873, notary Louis-Michel Darveau depicted Garneau as a victim of the clergy and of narrow-minded readers, and such first-hand testimony must be considered. Alfred Garneau did not publish anything about his father, but his correspondence provides much private information, unavailable elsewhere. In his introduction to the fifth edition (1913–20), Hector Garneau, Alfred’s son, describes the life of “the national historian,” adding several new facts, no doubt learned from family sources. His François-Xavier Garneau favours secularization and is less conciliatory than the man depicted by Casgrain and Chauveau, and his portrait rekindled debate on the meaning of Garneau’s work, especially his treatment of religious questions.

In 1926, Gustave Lanctot* published François-Xavier Garneau (Toronto) which was reprinted with minor changes in 1946 as Garneau, historien national (Montréal). It is a well-informed study, and its judgements are carefully considered. Since that time various works, the most important of which are listed in the bibliography of the critical edition of the Voyage prepared by Paul Wyczynski, have added to our knowledge of Garneau. Additional material can be found in the archives of the Projet Garneau at the Centre de Recherche en Civilisation Canadienne-Française at the University of Ottawa, which is described in the centre’s Bulletin of April 1973. A critical edition in 12 volumes of François-Xavier Garneau’s complete works is being prepared for publication by the authors of this biography. It will include a descriptive and critical bibliography of his life and works. p.s. and p.w.]

Cite This Article

Pierre Savard and Paul Wyczynski, “GARNEAU, FRANÇOIS-XAVIER,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 13, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/garneau_francois_xavier_9E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/garneau_francois_xavier_9E.html |

| Author of Article: | Pierre Savard and Paul Wyczynski |

| Title of Article: | GARNEAU, FRANÇOIS-XAVIER |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1976 |

| Year of revision: | 1976 |

| Access Date: | February 13, 2026 |