Source: Link

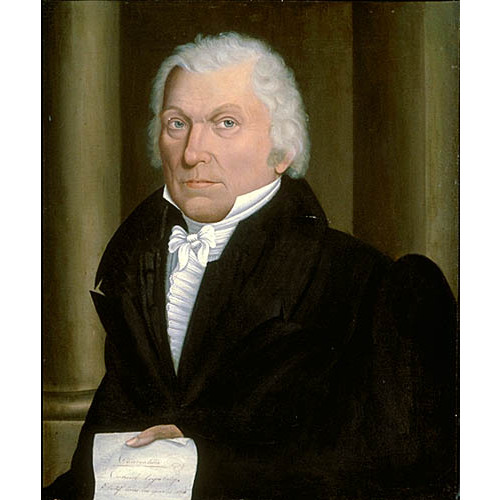

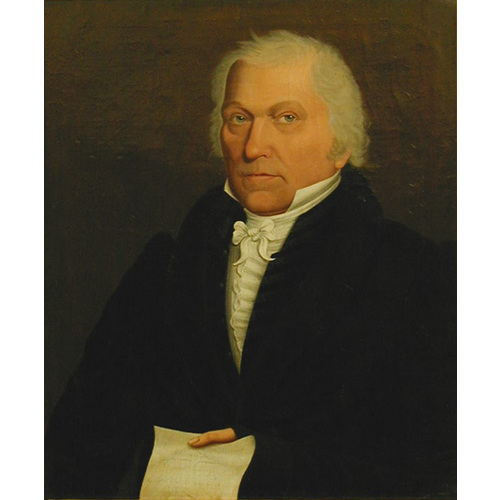

BOURDAGES, LOUIS, sailor, farmer, landowner, politician, militia officer, notary, and office holder; b. 6 July 1764 in Jeune-Lorette (Loretteville), Que., son of Raymond Bourdages*, a surgeon and merchant, and Esther Leblanc; d. 20 Jan. 1835 in Saint-Denis on the Richelieu, Lower Canada.

During the winter of 1756–57 Raymond Bourdages left Acadia with his family to settle at L’Ancienne-Lorette (Que.); once there, he practised medicine and engaged in trade. In 1762 he established himself on Baie des Chaleurs, where he set up two trading posts. Like many other Acadian families in the area, the Bourdages found themselves in a precarious situation because they lacked capital, were exposed to pillaging by American privateers and raiding by the Indians, and were at the mercy of the British government, which refused to give formal recognition to title deeds. With a childhood spent in this setting of chronic uncertainty, Louis early became aware of the misfortunes of his people and learned to curse the British authorities.

In 1777 his parents sent him to study at the Petit Séminaire de Québec, where a whole new world opened before him. He owed much to his family background and his Acadian origins, but he would owe his intellectual training and religious education to the Petit Séminaire. He likely stood out through his love of study and his lively intelligence. At any rate he reputedly was gifted in mathematics and philosophy and at the end of his studies defended a thesis in those subjects. He was also interested in matters of public concern and made friends with fellow student Pierre-Stanislas Bédard.

Upon leaving the Petit Séminaire in 1784, Bourdages, who was bent on getting ahead and aware of his family’s financial difficulties, wanted to make money quickly. He became interested, therefore, in trade and went to sea. Although he failed to make his fortune, voyages to Europe and the West Indies opened new horizons, broadening his field of knowledge. In 1787, after his father’s death, he decided to settle for good in the province of Quebec. That year he petitioned Governor Lord Dorchester [Guy Carleton*], for legal recognition of his family’s title to landed property on Baie des Chaleurs. Despite numerous letters and requests, the British government would not settle this question until 1825.

Since he had inherited nothing from his family and had no financial backing, Bourdages was reduced to his own resources. Nevertheless, he was thinking of getting married, and on 9 Oct. 1787 at Quebec he took as his wife Louise-Catherine Soupiran. The dowry, jointure, and preference legacy set out in the marriage contract make it clear that the couple both came from modest circumstances. Three years later, having been unsuccessful as a merchant at Quebec, Bourdages moved to Saint-Denis on the Richelieu. He may well have made this choice because several Acadian families had already settled there. At that time he was just a small farmer of no means and he had to support his family in precarious circumstances. In 1791 he bought some land that he farmed himself. Hardworking and tenacious, he took up selling firewood to the habitants in surrounding parishes. In 1799 he managed to buy another piece of land. In property assets, he already vied with a number of the landowners at Saint-Denis.

With his family’s livelihood assured, Bourdages turned to the notarial profession. He began his clerkship in 1800 with notary Pierre-Paul Dutalmé and completed it with Christophe Michaud, both residents of Saint-Denis. During this period he farmed his land and carried out financial transactions that imply a degree of prosperity. Among other things he owned a stone house in the village and held nearly 200 arpents in the seigneury. On 8 Jan. 1805 he received his commission as a notary and fell heir to the clientele of his colleague Michaud, who had given up practice the preceding year.

As a landowner and rural notary Bourdages came to play an important role in his milieu. First he was appointed agent for the seigneury and he became trustee for the funds of several merchants. Having business relations with habitants, seigneurs, and merchants, and being active in parish life, he frequently held positions of a representative nature. In 1802 he was elected syndic of the parish to bring the church building to completion; he already exercised significant influence in the militia as adjutant. He may even be suspected of inflaming disputes with his parish priest. Not only had he been attending, as a leading citizen, the meetings of the fabrique since the beginning of the century, which he had no right to do, but he also backed the habitants in their protests against the parish administration. Given their ways of thinking and their power in the parish, the curé and Bourdages were bound to clash on many fronts. None the less, because of his wealth in land, his education, and his family connections, Bourdages managed to reach the top rank in the community. His rise in society also was in keeping with the rise of the liberal professions in Canadian society in the early 19th century and the development of a liberal and nationalist ideology within that group.

Like many in these professions, Bourdages saw in the machinery of politics a powerful means for securing prestige and authority. On 6 Aug. 1804 he was elected to the House of Assembly for Richelieu, and he retained this seat until March 1814. His political career began at a time when the assembly was controlled by members in the liberal professions and by small Canadian businessmen. These new leaders were beginning to find their voice within an organized political group, the Canadian party. They became advocates of Canadian nationalism, denouncing the colonial rulers, in the shape of the governor and the largely English-speaking members of the councils. Like a number of assemblymen, Bourdages felt that this oligarchy jeopardized the interests of his group and was a threat to the Canadian collectivity. In this context he approved the Canadian party’s strategy, which was to weaken the existing colonial political power by demanding administrative reforms and seeking the support of the parliament in London.

Bourdages, who was a skilful tactician and an eloquent, persuasive orator, quickly established himself as a seasoned parliamentarian. In 1806 he attracted his colleagues’ attention by seconding the motion made by his leader, Pierre-Stanislas Bédard, condemning an article in the Montreal Gazette about the rather sarcastic toasts proposed by some Montreal merchants at a banquet presided over by Isaac Todd*. That year he helped found the newspaper Le Canadien. A year later he tried to get the house to vote an expense allowance to members from outside the town of Quebec. He early became identified with the interests of his constituents, presenting a number of petitions and bills about matters of local and regional concern. Aware of Bourdages’s skill in debates and popularity in his riding, Bédard entrusted him with several important tasks in the house. In 1808 Bourdages sponsored a bill to make judges ineligible to sit in the assembly [see Pierre-Amable De Bonne*; Sir James Henry Craig*]. In reality this dispute over the eligibility of judges, along with the later one over supplies [see Sir Francis Nathaniel Burton] marked the beginning of a struggle for the control of political power. Bourdages again supported Bédard when he called for ministerial responsibility, and he brought forward a motion to this effect himself. He unquestionably played an important role within the Canadian party at that period. He had always backed Bédard’s leadership and had generally felt a sense of solidarity with this first generation of Canadian assemblymen, who largely came from the Quebec region. When those responsible for Le Canadien – Bédard, François Blanchet, and Jean-Thomas Taschereau – were imprisoned in March 1810, Bourdages was without doubt the member who opposed most vigorously this drastic step taken by Governor Craig.

The War of 1812 led to a lessening of tension and a marked rapprochement between the executive and the leaders of the assembly. Bourdages sided with the British in the fight against the American invader. On 18 March 1812 he was promoted major in the Saint-Denis battalion of militia by Craig’s successor, Governor Sir George Prevost*. The following year he replaced merchant Joseph Cartier as the battalion’s lieutenant-colonel, though not without some unpleasantness. Bourdages, who displayed uncommon zeal and was inflexible with his men, soon came into conflict with some of the local leaders. Among other things he was accused of wanting to run the militia and of meddling in the affairs of others. In 1814 Prevost made him superintendent of post houses in the colony at an annual salary of £100.

In this narrow and compartmentalized society, everyone was anxious to protect his interests and coveted the favours enjoyed by his neighbour; hence feuds between cliques, private animosities, and personality conflicts all loomed large. In the general election of 1814 Pierre-Dominique Debartzch*, a legislative councillor who was the seigneur of Saint-Hyacinthe and was assured of support from the prominent local people, campaigned vigorously against Bourdages and managed to secure his defeat in Richelieu riding. Bourdages was humiliated and sought to revenge his honour. In January 1815 he persuaded the assembly to void the election by alleging numerous irregularities at the polls. This sort of fight sometimes turned Bourdages into the head of a clan that was regional in its outlook and in its chauvinism, primarily concerned with petty local annoyances and quite closed to the real matters at stake in the politics of the time. That year by-elections were called in Richelieu and Buckingham and he stacked the odds in his favour by running in both. He was again defeated in Richelieu but he won in Buckingham. Governor Prevost’s departure precipitated another general election in March 1816. Bourdages was beaten once more and had to resign himself to quitting politics.

He took advantage of the opportunity to give more attention to his profession and his family. The bonds of fellowship uniting this petit bourgeois family were indeed exemplary. In his wife Bourdages had a well-informed and supportive companion. The children were also closely attached to the family group, and to its sense of power and prestige. The boys began classical studies at an early age, held important posts in the militia, and participated in the daily affairs of the parish. Some of the girls had already married well. Proud of his family and anxious to leave a substantial inheritance, Bourdages, who was now in his fifties, became a real estate promoter and speculator. He practised as a notary with equal zeal, entering in his minute-book an average of 120 acts a year. In 1819 the British government granted him 1,200 acres in Ely Township for his militia service. Not taking offence or backing out, he simply accepted the offer. Like others in the professions, he did not worry about the contradiction implied in fighting the Executive Council while accepting profitable posts and favours from the government. By now he was one of the largest landowners in the district.

In 1820 Bourdages again won election in Buckingham. At Quebec the quarrel over the civil list was the centre of debate in the assembly. Louis-Joseph Papineau* engaged in open conflict with Governor Lord Dalhousie [Ramsay*] and increasingly asserted himself as the new leader of the Canadian party. These matters certainly were of concern to Bourdages. Once more he showed himself to be stubborn. and astute as a parliamentarian, seizing every chance to attack the executive and the English-speaking oligarchet he entered into the assembly’s everyday business as usual; he sat on numerous committees and dealt with his riding’s problems. In 1822 the proposed union of Upper and Lower Canada and the systematic opposition of the English-speaking merchants to seigneurial tenure again made the climate more difficult. Although the union bill fell through in Britain, the Canada Trade Act, which favoured the transfer of lands held in fief and roture into free and common socage, was passed. Bourdages reacted violently to this act of the British parliament. In 1824, even though he was not supported by Papineau and Denis-Benjamin Viger*, he put forward a motion to repeal the measure, but in vain.

In spite of everything, Bourdages was not against the development of capitalism in the colony; indeed he apparently favoured it in so far as it advantaged his own people. For example, he opposed the bill to develop a canal system on the St Lawrence, which was bound up with the interests of the British merchants, but he promoted a similar endeavour on the Rivière Chambly (Rivière L’Acadie), which would favour the regional interests of the Canadian bourgeoisie. It seems difficult under these circumstances to see him as a defender of a form of society that had existed under the ancien régime. All things considered, he agreed with the majority of his fellow members of the assembly, who talked of democracy and separation of church and state yet unhesitatingly defended the seigneurial system.

None the less the Canadian party did not present a united front at this time. The quarrels over Papineau’s leadership, the numerous personality conflicts, and the old rivalry between Quebec and Montreal members of the assembly had the effect of weakening the party and openly encouraging dissidence. Bourdages clashed primarily with Papineau. Since he backed the members from the Quebec region, he found it hard to accept the idea that the party would be run by someone from Montreal. He very much wanted to take Papineau’s place as speaker of the assembly, but he quickly realized that he did not have enough support in the house. In 1823, after Papineau left for London, with the help of others in the assembly he got the member for Upper Town Quebec, Joseph-Rémi Vallières* de Saint-Réal, elected speaker. Upon his return Papineau resumed the office and took care not to lay himself open to his enemies. He was aware of the danger that Bourdages and a few other members from the Quebec region represented and took advantage of the victory in the 1824 elections to strengthen his leadership and unite the party. In 1826 the Canadian party became the Patriote party. It rapidly consolidated its base and equipped itself with a party newspaper, La Minerve. Electoral victory in 1827 unequivocally established Papineau’s leadership. In his self-confidence he reoriented the party’s strategy and went beyond complaints concerning administrative matters to demand complete control of the budget by the assembly and an elective legislative council. Being confronted with the fait accompli, Bourdages and other members had no choice but to adjust rapidly to the new political realities.

In 1830 Bourdages, recently elected in Nicolet, threw his weight behind Papineau and his ideas. His unconditional support of the Patriote party was confirmed at every vote by roll call in the house. Like his leader, he attacked the clergy who openly opposed the Patriote cause. In 1831 he joined with Papineau to put forward a bill on the fabriques designed to reduce the powers of the curés in parish administration by giving to all property owners the right to be present at meetings held for the election of wardens and the presentation of financial statements. He had often battled with his priest, and he saw in the bill an excellent means for the local élite to intervene in parish matters. The political needs of the past few years also prompted him to bolder views on nationalism. He was amongst those who believed that the British parliament had deceived the House of Assembly and that revolution was inevitable. On this matter he had even more advanced ideas than Papineau. The cholera epidemic in the years 1832–34, the dramatic decline in the francophone population in the towns and the increasing numbers of anglophones, the poor harvests in the preceding years, and the repressive measures carried out by British troops following the by-election in Montreal West in 1832 [see Daniel Tracey] intensified national animosities and incited the population to agitation and revolt.

As he neared 70, Louis Bourdages attracted notice more and more as a political radical. But, however bold he was, he never went beyond a prudent search for reform in the religious sphere and always maintained a strict respect for seigneurial property. He represented well a large section of the petite bourgeoisie of the period, which wanted to change the political system in the colony without upsetting the social structure. He carried out one of the last important acts of his political career when he helped develop and publicize the 92 Resolutions setting out the assembly’s main grievances and requests.

Bourdages suffered an attack of apoplexy on 11 Jan. 1835 and, with the consolation of the last rites of the church, died on 20 January. In his will, which he had drawn up on 6 Aug. 1833, he left 7,142 livres, a considerable number of properties, and net assets of more than 100,000 livres. His stone dwelling was furnished elegantly and tastefully, with hangings, an antique china table service, and silver plate. His library contained nearly 100 volumes and suggests that he was attracted to philosophical thought, democratic ideas, and the business world.

Louis Bourdages’s minute-book, containing instruments notarized between 1805 and 1835, is held at the ANQ-M, CN2-11.

ANQ-M, CE2-12, 23 janv. 1835; CN1-134, 4 mars 1818; CN1-168, 19 nov. 1821, 30 sept. 1822; CN2-19, 22 mars 1822, 28 juill. 1827; CN2-27, 18 juill. 1799, 13 août 1801, 9 mai 1804, 29 juill. 1811, 18 mai 1819; CN2-56, 15 mars 1791; CN2-57, 7 déc. 1824. ANQ-Q, CE1-1, 9 oct. 1787; CN1-83, 6 oct. 1787. AP, Saint-Denis (Saint-Denis, sur le Richelieu), Cahier des délibérations de la fabrique, 1797–1845. ASQ, Fichier des anciens. ASSH, Fg-12, dossier 7, boîte 13. PAC, MG 24, B2. L.C., House of Assembly, Journals, 20 March 1815, 27 Jan. 1818. Réponse à Testis sur les procédures d’une cour d’enquête, sur plainte du lieut. colonel Bourdages . . . ([Montréal], 1816). F.-J. Audet, “Les législateurs du Bas-Canada.” Desjardins, Guide parl. Officers of British forces in Canada (Irving). J.-B.-A. Allaire, Histoire de la paroisse de Saint-Denis-sur-Richelieu (Canada) (Saint-Hyacinthe, 1905). Maurice Grenier, “La chambre d’Assemblée du Bas-Canada, 1815–1837” (thèse de ma, univ. de Montréal, 1966). F.-J. Audet, “Louis Bourdages,” RSC Trans., 3rd ser., 18 (1924), sect.i: 73–101. Fernand Ouellet, “Papineau et la rivalité Québec–Montréal (1820–1840),” RHAF, 13 (1959–60): 311–27.

Cite This Article

Richard Chabot, “BOURDAGES, LOUIS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 6, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 9, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bourdages_louis_6E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bourdages_louis_6E.html |

| Author of Article: | Richard Chabot |

| Title of Article: | BOURDAGES, LOUIS |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 6 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1987 |

| Year of revision: | 2013 |

| Access Date: | February 9, 2026 |