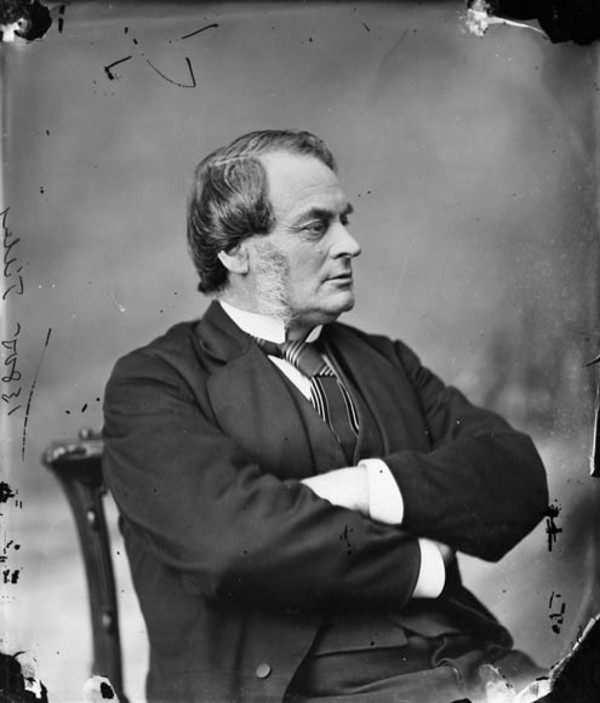

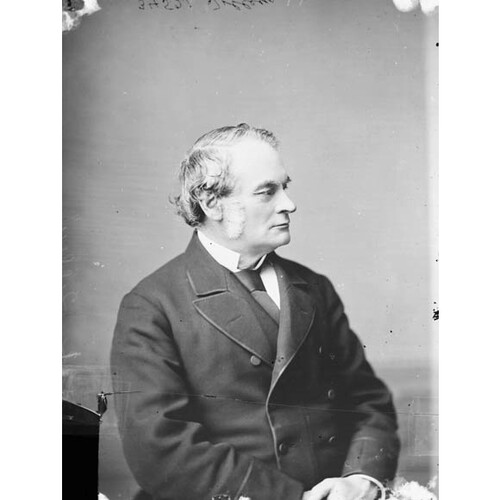

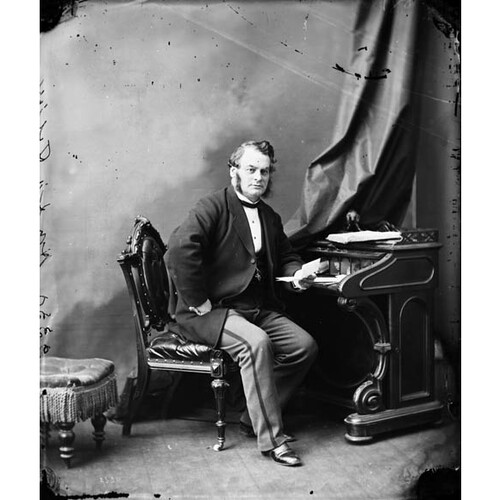

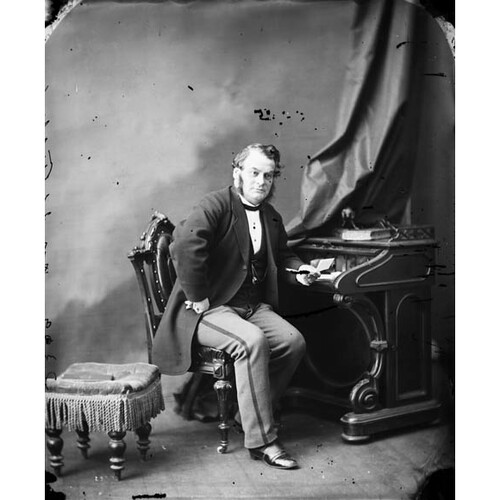

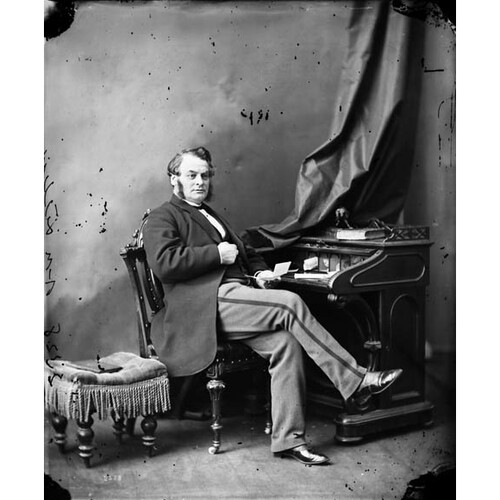

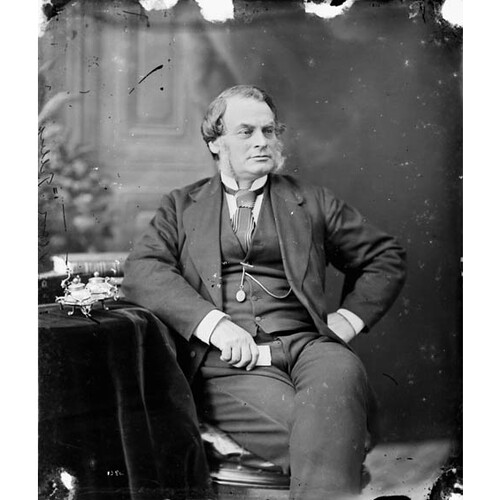

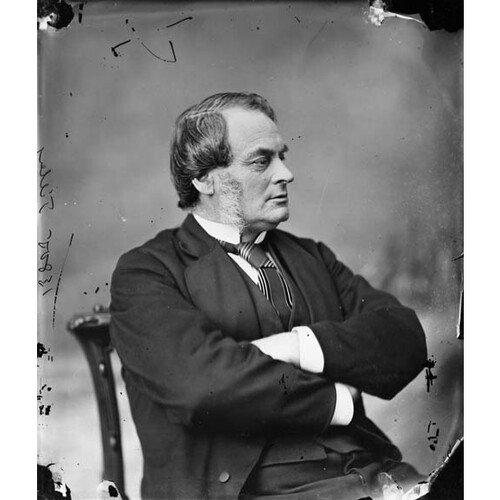

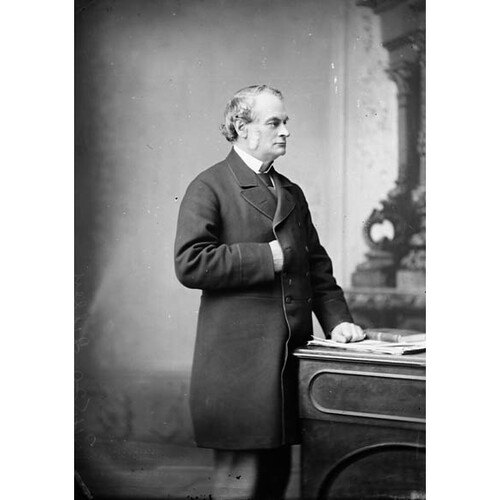

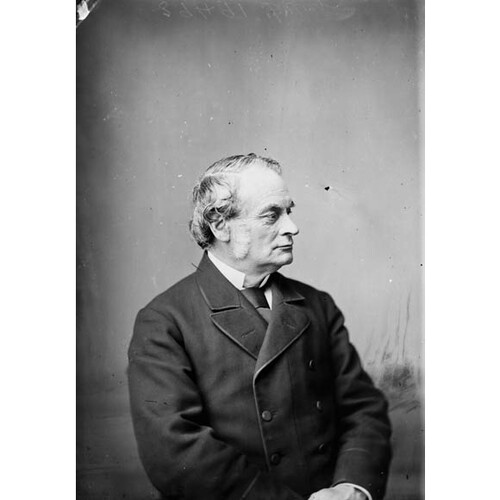

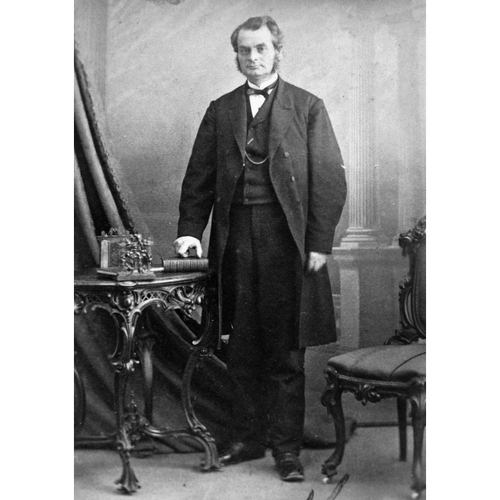

TILLEY, Sir SAMUEL LEONARD, druggist, politician, and lieutenant governor; b. 8 May 1818 at Gagetown, N.B., eldest son of Thomas Morgan Tilley, a storekeeper, and Susan Ann Peters; m. first 6 May 1843 Julia Ann Hanford in Portland (Saint John), N.B., and they had eight children; m. secondly 22 Oct. 1867 Alice Starr Chipman in St Stephen (St Stephen-Milltown), N.B., and they had two children; nominated kcmg 24 May 1879; d. 25 June 1896 at Saint John.

A descendant of loyalists on both sides of his family, Samuel Leonard Tilley received his first four years of education at the Church of England’s Madras school [see John Baird*] in Gagetown. In 1827 young Lennie or Leonard, as he was called, moved on to the local grammar school, where four more years completed his education. He was 13 in 1831 when he left to live in Portland with relatives and apprentice as a druggist in adjoining Saint John. In May 1838, a certified pharmacist, he went into partnership with a cousin, Thomas W. Peters, to open Peters and Tilley, “Cheap Drug Store!” When Peters retired in 1848 it became Tilley’s Drug Store, one of the more successful commercial operations in the city. By 1860 politics had taken over Tilley’s life, however, and he sold the business.

Tilley’s entrance into public life was partly an extension of his involvement with the temperance movement, which, in turn, grew out of his religious convictions. A low-church Anglican, he was so moved by a sermon of the Reverend William Harrison in 1839 that he made a “new departure.” From that time his evangelical religious belief, with its emphasis on the Bible and faith with a social conscience, would be a dominant factor in his life. He taught Sunday school, eventually became a churchwarden, and was a committee member of the Saint John Religious Tract Society.

Tilley and Harrison were part of a growing body of opinion that viewed liquor as the major social evil. By 1844 Tilley was on the committee of the Portland Total Abstinence Society, working for legislation that would enforce prohibition. An especially brutal butcher-knife murder of a woman by her drunken husband may have haunted him. The 11-year-old daughter ran for help, and Tilley was in the vicinity. Never, he declared, would he forget the scene. “There lay the mother weltering in her blood, her little children crying around her, and the husband and father under arrest for murder; and rum the cause of it all.” The Sons of Temperance, an American movement which had emerged from the evangelical “experience meetings” of the 1840s, provided the organization necessary for the advocates of prohibition to become politically effective. A few months after the first New Brunswick branch opened on 8 March 1847, Tilley was on the executive of the provincial body, one he came to dominate. After 1848 no temperance soirée, demonstration, lecture, or international conference was complete without him. He was not a rabble-rouser on the platform; rather he used cold logic and colder statistics. In 1854 he was elected to the highest position in the Sons of Temperance, most worthy patriarch.

Despite appearances, Tilley was not a temperance fanatic. His family and his religion always took precedence in his life, and politics would eventually replace temperance as his passion. While a young man Tilley had joined the Saint John Young Men’s Debating Society. The Saint John Mechanics’ Institute then caught his attention, and in 1842 he became the treasurer, with responsibility for cleaning up a financial mess. That organization was a vital body during the 1840s, having among its members business and political leaders such as William Johnston Ritchie, John Hamilton Gray*, John Robertson*, George Edward Fenety, and Robert Duncan Wilmot. It provided a vehicle for all sorts of ideas, such as those of Dr Abraham Gesner* on the necessity of protection for infant industries.

The recession of 1848, and its close identification with the loss of British preferences, forced the Saint John business community to make adjustments. Tilley accepted Gesner’s point of view and called for protection. He also became a founding committee member of the Rail-Way League which had as its premise: “Whoever labours for the introduction of Railways . . . is working for humanity – for progress – and for the highest good of his race.” That league, in turn, became the nucleus of the New-Brunswick Colonial Association, which was organized on 28 July 1849, with Tilley as treasurer and a member of the rules committee. The association condemned Britain for abandoning its colonies, called for protection of agriculture, industry, and fisheries, and moved for a “Federal Union of the British North American Colonies, preparatory to their immediate independence.” Though that final motion was withdrawn, after being approved by a mere one-vote majority, the intensity of the feeling cannot be overestimated.

Tilley’s rules committee called for provincial control of the civil list and all public expenses, a public school system, government control of public works, and, above all, honest government. The provincial election of 1850 gave the association and Tilley their opportunity. Joseph Wilson Lawrence, Tilley’s best friend, spoke in his favour on nomination day, calling him “a steady and zealous advocate of all the leading measures of reform.” Tilley led his poll, one of six members elected for the association in Saint John. In the assembly he did his best for temperance by presenting several petitions in favour of making liquor dealers “responsible for any injury arising out of the traffic.” His skill with figures put him on a committee to study contingency expenses. More about him is revealed by his speeches. Although he attacked the inherited and acquired privileges of the gentry, he was against giving the vote to men who did not own property. He was a member of that new class of successful New Brunswickers who, while not democratic, rejected the loyalist tradition of obedience to established authority. “A Government that trampled upon the rights ceded to the Colonies, did not command the respect of a free people,” he declared in a near-successful attempt to force the resignation of the Executive Council in the spring of 1851.

Lieutenant Governor Sir Edmund Walker Head* castrated the reform opposition over the summer that year by enticing two members of the New-Brunswick Colonial Association, Gray and Wilmot, to join the council. So incensed was Tilley that he resigned his seat in protest when Wilmot was re-elected in October. Fellow reformers William Johnston Ritchie and Charles Simonds* also resigned. Head rejoiced, and Tilley’s political career appeared over, yet for him politics, religion, and temperance were so closely interwoven that he could not abandon any of them. He worked enthusiastically for temperance and was instrumental in having a prohibition act passed in 1852, though it failed in its objectives. As a low churchman he led the charge in the Church of England against the tractarian bishop of Fredericton, John Medley.

The provincial election of 1854 returned Tilley and a majority of like-minded members from across the province. Head and Medley and all they represented had been the catalyst that united the reformers behind Charles Fisher*. On 1 November the Reform government was in place, with Attorney General Fisher the leader and Tilley his provincial secretary.

The office of provincial secretary was the most demanding in the Executive Council. It reached into every corner of the province and most directly affected the people. All matters of roads and bridges, all aspects of finance and revenue, education, health, industry and trade crossed Tilley’s desk. A board of works, whose creation was one of his promises, took over the roads and bridges, and a number of other reform measures were passed. Tilley, although he supported all the measures, is irrevocably associated with two in particular, an effort to put control over finances into the hands of the Executive Council and an attempt to institute prohibition. On 21 Feb. 1855 he introduced the first revenue bill in the province’s history that tried to assume responsibility for its finances, which traditionally had been in the hands of the assembly, as well as to use tariffs in the control of trade. He sought a balanced budget with, he said, “a view to encouraging as much as possible domestic industry.” Tilley was called New Brunswick’s first chancellor of the exchequer for this budget, and though he lacked control over the initiation of money grants in the technical sense, that was the next step. A month later he brought in the most controversial legislation of his career, the Prohibition Bill. It was a repeat of previous legislation, but the penalties were new and severe. They included arbitrary arrest and imprisonment and the incarceration of intoxicated people until they revealed their source of supply. Though the bill became law, it was opposed aggressively by Tilley’s own colleagues in the government, Ritchie and Albert James Smith*. As soon as it came into effect, on 1 Jan. 1856, Tilley found the act and himself under continuous attack. While he never flinched in its defence, he was burned in effigy, his house was attacked, and he worried about threats on his life. Violations of the legislation and the failure to get convictions led to a minor state of anarchy. Lieutenant Governor John Henry Thomas Manners-Sutton*, who disliked his councillors generally and the Prohibition Act as well, took decisive action on 21 May 1856 by dissolving the assembly. Gray and Wilmot put together a new council, ran the election, and swept the province, with help from, among others, Bishop Medley and the old establishment. What was worse for Tilley, long-time friends such as Lawrence turned on him, defeating him at the polls.

Tilley was back to being a “Pill Seller” in Saint John where his wife Julia, who had not joined him in Fredericton, and their large family welcomed him with enthusiasm. The drugstore provided a comfortable annual income of about £1,200 and he owned substantial properties valued at between £10,000 and £15,000. His home, his church, and his business might have been enough, but they were not. Tilley craved a role in politics. As provincial secretary he had managed the whole spectrum of issues. The Reformers had been a good government and he had been an effective member of it. Indeed, what had infuriated his critics most was his domination of the council. Whether it was his thoroughness, his Spartan work habits, his control of the finances, or his persuasiveness, he had got his way on policies, appointments, and priorities. Realizing that prohibition had failed through lack of public support, he vowed to leave the matter to plebiscite. He realized as well, even as his Prohibition Act was being repealed, that the Gray-Wilmot government lacked direction, and the day was past when the lieutenant governor’s chosen men could direct the assembly. Another election was under way early in 1857. On the hustings immediately and running as a Reformer, not a prohibitionist, Tilley led the poll as did a majority of his former colleagues. A chastened Manners-Sutton was compelled to ask Fisher to form a government. On 9 June Tilley returned to the provincial secretary’s office, where he would remain for eight years. That he planned to stay in Fredericton was made clear in October when he moved his family to the capital with him.

The depression of 1857 greeted Tilley as soon as he took office, and it would provide several dreary years. Determined to balance his budget, he raised tariffs, with a tendency towards protection, and kept expenses in line. A bank failure and the closure of several businesses threatened all of Tilley’s projections. Baring Brothers and Company of London, the international financiers, rode herd on him but concluded in 1860, “There is everything in the conduct of the Province to inspire the public as well as ourselves with greatest confidence in the good faith of the Government.”

This confidence was remarkable because the province had committed itself to a staggering public expense for the European and North American Railway, the line from Saint John to Shediac that had inspired the old Rail-Way League of 1849. Work had been going on for some years, but the project faced bankruptcy and was saved only when the Fisher government took it over in 1856. For the remainder of the 1850s the line was under construction and scrutiny. Although inquiries rejected charges of mismanagement and patronage as largely groundless [see John Hamilton Gray], they did provide public entertainment, much of it at Tilley’s expense. He learned to be philosophical about the abuse, for the construction provided essential employment during difficult years. The accumulated debt was probably more than the province could bear, but the completion of the railway on 8 Aug. 1860 represented progress to Tilley, especially for Saint John.

Although finances and the railway dominated Tilley’s endeavours, the other demands of his office were great. Moreover, Fisher was in frequent conflict with Manners-Sutton. Good councillors departed, such as Ritchie who was appointed to the Supreme Court, and were replaced by lesser men. Albert Smith thoroughly despised Fisher and would have left but for Tilley. Meanwhile, Tilley and the lieutenant governor became close friends and would remain so long after Manners-Sutton left the province. A crisis arose in 1861 when Fisher got caught in a crown land scandal. In one of the most daring moves of his career, certainly made in consultation with Manners-Sutton, Tilley called all members of the council except Fisher to a meeting on 14 March, collected their resignations, and presented them to the lieutenant governor, who refused to accept them. Five days later Manners-Sutton removed Fisher from the council and Tilley was in control. His government was returned with a comfortable majority in a June election.

Bold colonial politicians such as Tilley were not the type Arthur Hamilton Gordon*, the new lieutenant governor, expected or could tolerate. Tilley and his council met Gordon at Sussex on 24 Oct. 1861, a week before Tilley had to depart for England in pursuit of an intercolonial railway that would link Canada with the Maritimes. He made the crossing with Joseph Howe*, Nova Scotia’s provincial secretary and premier. They had become companions while Howe was on a lecture tour in New Brunswick, and they seemed to agree on everything: politics, government, railways. Their attempt to get British government financing failed, however, and with the onset of the Trent affair in November [see Sir Charles Hastings Doyle*] Tilley rushed home to assist his volunteer militia in the transportation of British troops across New Brunswick. He immediately ran foul of Lieutenant Governor Gordon, who considered all military matters under his jurisdiction. To make matters worse, Tilley had returned very ill. Then his wife also became ill, apparently with cancer. On 27 March 1862 she was dead. “Unremitting, anxious, hard work” was Howe’s advice to the despondent Tilley. Perhaps he followed the advice, for he did seem driven over the next few years.

That June Howe came to get Tilley and the two of them went to Quebec to see Governor General Lord Monck and the Canadian government about yet another intercolonial railway adventure. Tilley led a New Brunswick delegation back to Quebec in September where an agreement was reached to share the costs if the imperial government guaranteed the loans. Albert Smith, opposed to government-owned railways in principle and to any increase in the provincial debt, resigned from the Executive Council on 10 October. Tilley appeared not to care. He had the intercolonial in his sights. Within the week he and Howe were on a Britain-bound steamer to make another try for imperial assistance. Since all they were requesting was a guarantee for their loans, they got their wish on 29 November, though Chancellor of the Exchequer William Ewart Gladstone did stipulate that there must be provision for a sinking fund. By Christmas Tilley was home with his motherless children, thinking his railway dreams all fulfilled. He had overestimated the enthusiasm of the Canadian representatives. William Pearce Howland* and Louis-Victor Sicotte* refused to accept the sinking fund and scuttled the agreement after Tilley left London. Tilley had confidence in Upper Canadian leader John Sandfield Macdonald*, however, and spent four cold days and nights on an overland trip from Fredericton to Quebec to confront the Canadians on 21 Jan. 1863. He “battled gallantly with the shabby fellows at Quebec,” as the colonial secretary, the Duke of Newcastle, put it, but the deal was off. Tilley was not one to give up. The intercolonial had become an obsession, and despite the Canadian rejection he pushed enabling legislation through the New Brunswick assembly in a memorable debate which obliterated the party lines that had held for almost a decade. The opposition was led by Albert Smith.

In Nova Scotia Howe’s government was defeated in the spring of 1863, but Charles Tupper*, Howe’s replacement as provincial secretary and premier, was known to support the intercolonial. In the Canadian election that spring the government of J. S. Macdonald and Antoine-Aimé Dorion was returned, although with a precarious majority, but the good news for Tilley was that Thomas D’Arcy McGee*, a strong advocate of the intercolonial, had gone to the opposition. Tilley decided to do all in his power to embarrass the Canadian government. Official correspondence was used as a platform to denounce the Canadians’ duplicity. When they finally agreed to a survey of the intercolonial route, Tilley decided he too could be impossible. His hope lay with the opposition in Canada, and to a suggestion that he was hurting the cause he snapped, “I have no faith in the sincerity of the professions of the men now in power.” When the exasperated Canadians finally decided to undertake the survey on their own, he considered it a capitulation. By then he had turned his attention to a railway network for all of New Brunswick. In March 1864 he introduced the legislation sometimes called the Lobster Bill to subsidize railway lines going in several directions. He hoped to placate various regional interests and thereby undermine the growing opposition to the intercolonial in favour of an extension of the European and North American Railway west from Saint John to Maine.

The defeat of the Canadian government and its replacement by the coalition of John A. Macdonald, George-Étienne Cartier*, and George Brown* on 22 June 1864 was the event Tilley had been anticipating. In April and May he and McGee had already been planning another conference to promote the intercolonial. “Why might not our proposed Intercolonial Conference, be also held at Charlottetown, after your Maritime Conference?” McGee had asked on 9 May. Monck’s request of 30 June for permission to let a Canadian delegation attend the conference in Charlottetown, which had been organized to discuss Maritime union, did not, therefore, surprise Tilley.

Tilley had no particular interest in Maritime union. He had bigger things in mind. From as early as 1849 and the days of the New-Brunswick Colonial Association he had wanted some form of British North American association along the lines of a zollverein. By 1863 he was asserting that the “condition of affairs” demanded a change in political structures, even a union with Canada, for there could be no commercial union without political union. He was even more explicit the following summer. At a public dinner on 9 Aug. 1864 he described the intercolonial railway as a stepping-stone to British North American commercial and political union. Statesmen, he argued, should try “to bind together the Atlantic and Pacific by a continuous chain of settlements and line of communications for that [was] the destiny of this country, and the race which inhabited it.” Tilley carried that outlook into the Charlottetown and Quebec conferences in September and October. He came out against Maritime union and was the seconder of Macdonald’s pivotal motion at Quebec for federal union. His interjections, it appears, were rare, but never frivolous. His energies were reserved for critical issues, such as the maintenance of strong provincial governments, and the equitable distribution of federal moneys. According to a reporter from the Montreal Gazette, “Any ordinary man can open an argument, most men can keep it up, but Mr. Tilley always knows where the matter ends.”

When Tilley returned to New Brunswick on 9 November it was to a “strong current running against Federation,” and he announced publicly that the legislature “would not be asked to pass any resolutions until the people first had an opportunity of voting upon it at the polls.” The fate of his Prohibition Act may have been a factor in the decision. It does not matter that he may have agreed at Quebec not to submit confederation to the people. His council apparently refused to follow that route; even if they had agreed, he could not possibly have carried a majority in the assembly, and his mandate would run out in June 1865. Tilley anticipated that the election, which began on 28 February, would be an “animated & warm contest,” but he did not expect a massacre. He fumbled the campaign, however, by failing to sell confederation properly or to end confusion over the intended route of the intercolonial railway. Moreover, many people voted “from their hatred of the Govt. and from their desire to oust Tilley who they thought had been too long in power,” according to John Hamilton Gray. A mere handful of Tilley’s supporters survived Albert Smith’s onslaught, and Tilley personally was defeated.

Smith and the anti-confederates would have the backing of between 25 and 33 members in the assembly of 41, depending on the issue. Matters were grim, yet there was a familiarity to the situation. Nine years earlier Tilley had faced a similar rejection over prohibition, but he was back within a year. Smith was surrounded by disparate spirits, and Tilley was convinced his government would destroy itself as long as the pro-confederates did not make any mistakes. At the same time nothing should be made easy for Smith, and it was not. Soon government supporters in the assembly and the council began to discover they had other priorities. As the months passed, Timothy Warren Anglin, R. D. Wilmot, and Andrew Rainsford Wetmore, all Saint John men, resigned or abandoned him, though Anglin never went to the opposition. Meanwhile Tilley was stumping the province with the confederation message.

The return of Lieutenant Governor Gordon from England in October 1865 with orders from Colonial Secretary Edward Cardwell to have confederation adopted promised more difficulties for Smith and for Tilley, with whom Gordon began to cooperate. Tilley and Gordon would never like or trust each other. Tilley was especially concerned that Gordon not do something precipitate in his desire to please his superiors. On 7 April 1866 Gordon did. Without the approval or advice of his council he accepted a message in support of confederation from the non-elected Legislative Council, both an affront and a challenge to Smith. Smith, although he still had a small majority in the assembly, resigned and headed for the stump against the lieutenant governor for “prostituting the prerogative of the Crown.” Tilley was furious that Gordon had given Smith a battle-cry. In his view Smith would soon have lost his majority and the issue would have been clear.

The most important election campaign in New Brunswick’s history began on 9 May. Everything went Tilley’s way. Roman Catholic bishop James Rogers* of Chatham came out strongly for confederation. Money flowed to New Brunswick from Canada to help in the conversion of the uncertain. Had Tilley wished to create an accomplice to swing the doubtful he could not have improved on the Fenians, who invaded Indian Island near the mouth of the St Croix River on 14 April, thus revealing the necessity of the larger union for national defence. The raid also contributed to the pernicious anti-Catholic atmosphere that pervaded much of this election, despite Bishop Rogers. In the end, however, people had to choose either “union or disunion” and they chose union. “All the Saints in the Calendar must have been on your side,” wrote Nova Scotia confederate Jonathan McCully* to Tilley. He also reminded him that they must get the British authorities to act quickly on the union since Tupper’s majority would be “scattered to the four winds” in the election due to be called in that province by May 1867. Tilley acted immediately. A short session of the legislature passed the necessary resolutions, and on 19 July 1866 the Maritime delegates were bound for England.

That the departure was premature practically everyone agreed. The British had other priorities, and a Fenian invasion across the Niagara frontier [see Alfred Booker*] prevented the Canadians from leaving for some time. The Maritimers arrived at Liverpool on 28 July and would wait four long months. Tilley became so annoyed over the Canadian attitude that he considered abandoning the project. He wrote to Alexander Tilloch Galt on 9 August that he could not believe the Canadians could be so “discourteous to the delegates” as to leave them cooling their heels in England. The reply, which arrived three months later, was a nasty rebuke from both Galt and John A. Macdonald. Tilley was stung, as he told railway promoter Edward William Watkin, and indicated that he was going home. Perhaps Watkin talked him out of it. “Neither you nor I,” he said, “were made for another life,” and Tilley knew it. Macdonald had also held out a carrot, something about modifications in the original resolutions, that intrigued Tilley.

On 4 December the London conference was under way, and within the month the package was ready for the imperial parliament. As at Charlottetown and Quebec Tilley had been content to let others do the talking, but nothing got by him. Hector-Louis Langevin* surveyed the delegates and decided that Tilley was “an ingenious fellow, resourceful and upright.” Perhaps it was Tilley’s long experience with finances, but he was able to persuade the delegates to improve the grant to New Brunswick. There was one final and dangerous obstacle. An attempt was made to entrench a legal right to denominational schools in the Maritimes. Well aware of the intense feelings about that issue at home, Tilley and the other Maritime delegates would have withdrawn from the conference rather than accept.

The conference was over, but the question arose as to what description would be given to the new country. A kingdom perhaps? Most thought not. During one of his daily Bible readings Tilley is said to have been struck by Psalm 72:8, “His dominion shall be also from sea to sea.” He suggested this designation as appropriate, and others apparently agreed. The Dominion of Canada it would be.

Tilley remained for the passage of the bill through the British parliament and a visit with Queen Victoria before boarding the China for a fast trip across the Atlantic. He was back in New Brunswick for a hero’s welcome at the end of March 1867. A final pre-confederation sitting of the New Brunswick legislature provided for the construction of the Western Extension railway from Saint John to Maine, prohibited dual representation, and let Tilley present his final budget. All eyes were on Ottawa, and he was impatient to begin a new career there.

Tilley had been touted as the logical candidate for minister of finance since he was senior in terms of service. He certainly thought himself competent for the position, but it is doubtful whether Macdonald gave a second thought to a non-Canadian for such an important position. He was having trouble enough satisfying Canadians as it was. He offered Tilley the Customs Department and he asked him to select another New Brunswicker for the cabinet. Tilley chose Peter Mitchell, but not without serious reservations. On 1 July 1867 Macdonald, the prime minister and new knight commander of the Bath, was the first member of the Privy Council to be sworn in, followed by Cartier and then Tilley. Tilley was one of the ministers named companion of the Bath.

The summer of 1867 was eventful. Tilley had to familiarize himself with the Customs Department in Ottawa while looking after the “reconstruction” of New Brunswick, where he was determined to secure a pro-confederation Liberal-Conservative coalition. Elections for the federal house and by-elections for the provincial one had to be fought, and there was always his family. The two eldest children were ready to begin their adult lives, but the five younger ones were still at home. Tilley made more than a political change in 1867, however. On 22 October he married Alice Starr Chipman, the daughter of a close friend.

Customs was an inferior position in the cabinet, though Tilley was on the newly created Treasury Board. His role as minister was to oversee the extension into the Maritimes of the tariff and administrative arrangements of the old province of Canada, an onerous job. When Tilley introduced the new tariff structure on 12 Dec. 1867 he created an enormous backlash against confederation in the Maritimes and gave an additional weapon to Joseph Howe, who had been elected to the House of Commons and was determined to get Nova Scotia out of the union. Though a major revision in April 1868 brought the tariffs into line with those of New Brunswick before confederation, Tilley continued to be publicly regarded there as a man without influence in Ottawa. He could not get his nominees appointed to positions. The intercolonial railway was to be built on the North Shore route, over his objections. Tilley had had some hope of obtaining the finance portfolio when Galt resigned, but the Canadian primacy was clearly demonstrated when Macdonald offered it first to Howland and then to John Rose*, a man of limited parliamentary experience. The resignation of Rose and his replacement by another Canadian, Sir Francis Hincks*, in October 1869 left little doubt about Tilley’s expectations. By 1871 he was looking for a way out. The Treaty of Washington [see Sir John A. Macdonald] was being savaged in New Brunswick and Tilley with it. The death of his father on 24 April seemed to make something snap. Three days later he told Macdonald he was through, and he asked for the lieutenant governorship of British Columbia, the newest province. Macdonald apparently promised him the office, and Tilley gave notice to his Ottawa landlord.

Tilley’s spiritual departure in 1871 was undoubtedly necessary, if only because it forced him and Macdonald to consider their situation. In New Brunswick things had turned sour. Nothing that Tilley did was appreciated, and the debate over the New Brunswick Common Schools Act of 1871 [see John Costigan*] had poisoned the atmosphere. Little wonder that British Columbia looked inviting, yet it would be the end of active politics. Macdonald had to consider his cabinet without Tilley, a man who did the job well but was taken for granted. The Customs Department was running as smoothly as any despite the large increase in its responsibilities that confederation had entailed. One of the few original ministers left by 1871, Tilley was the only surviving member of the first Treasury Board. The other Maritimers in the cabinet, Tupper, Mitchell, and Howe, were all loud in their enthusiasms but precipitate and not always reliable. Indeed, Howe’s very presence owed something to Tilley. Howe had gone to Ottawa in 1867 insisting that Nova Scotia would be leaving, and it was Tilley who in July 1868, after meeting with Howe over dinner, had sent Macdonald word that he would be willing instead to talk about better terms. Tilley thought it nonsense to perpetuate injustices or give aid to anti-confederates by refusing to make changes in the original agreement that had brought the provinces together. The arguments of constitutional purists on the subject carried no weight with him.

Whether he changed his mind himself about leaving Ottawa or Macdonald persuaded him with an enticing offer, Tilley remained in the cabinet. He had already recovered some of his confidence. During the 1871 budget debate Galt had attacked the government, and Tilley demolished his arguments to “loud and prolonged cheers.” His mastery of detail, memory of incidents, and grasp of financial matters had moved Tupper to tell Macdonald early in March, “For the first time in this house he did himself justice.” Macdonald was impressed. He also knew that the difficult situation in New Brunswick needed delicate handling, and no one else had Tilley’s skills. Lurking just ahead was an election, for which Tilley was indispensable. Albert Smith, who led the anti-confederation forces to Ottawa in 1867, had discovered by 1871 that he had more to fear from the parochial Ontario and Quebec members of the opposition than from Macdonald. Tilley struck up an alliance with his old colleague and opponent, convincing him that he belonged in the Macdonald camp, and the two united to protect the New Brunswick schools legislation when it came under attack in Ottawa. With no opposition party running in the province, Tilley had an easier time in the 1872 federal election than expected. When the results were in, he thought the government could depend upon 12 of 15 New Brunswick representatives elected. Ontario was Macdonald’s weak spot.

Sir Francis Hincks was among those from Ontario who had fallen, and Tilley knew finance was his at last. Macdonald may have promised it to him a year earlier to keep him in the cabinet. By November Tilley was informing his friends that he would become minister once the Canada Pacific Railway issue was settled. Hincks took a safe British Columbia seat and stayed on in the department until the charter was granted to Sir Hugh Allan* on 3 Feb. 1873. On 24 February Tilley was sworn in as Canada’s fourth minister of finance in six years. His first budget on 1 April 1873 was his easiest. He had a surplus and a strong economy, and he pleased everyone, including the opposition.

Tilley was forgotten the next day when Lucius Seth Huntington* accused the government of having received large sums from Allan and his American partners during the election. Throughout that uncomfortable spring and summer Tilley watched the Macdonald majority slip away. Albert Smith held firm until the prorogation on 13 August which he called an “act of tyranny.” It was a troubled Tilley who left for England to oversee a £4,000,000 loan, which was taken up in four days, and just in time. A business panic precipitated by the failure of Jay Cooke and Company on 18 September marked the beginning of a major depression.

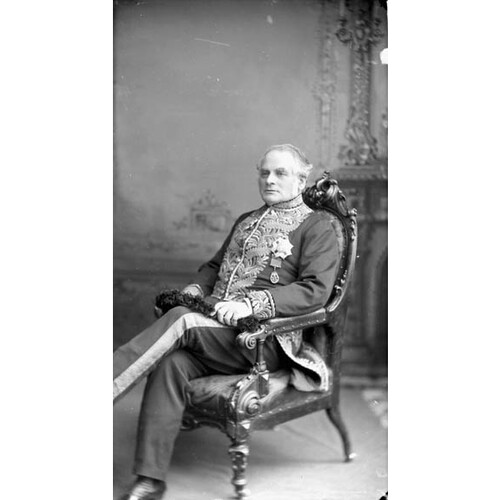

Back in the House of Commons Tilley made a great speech on 31 October in defence of the besieged Macdonald. When the government resigned on 5 November, he was appointed lieutenant governor of New Brunswick. He returned home in the midst of controversy. Prime Minister Alexander Mackenzie attempted unsuccessfully to have the appointment rescinded, but his minister of marine and fisheries, Albert Smith, defended it. Most people agreed with Smith that Tilley, then 55, deserved the lieutenant governorship, though Smith doubted he would be satisfied with a ceremonial position. For a couple of years Tilley seemed content. He read the speeches from the throne, attended the military levees, visited the University of New Brunswick, appeared at official functions, and held the obligatory receptions, from which, however, wine was banished.

Tragedy was to accompany Tilley in that office. Much of the Saint John he had known was burned in the great fire of 1877 [see Sylvester Zobieski Earle*], although Tilley’s own property was spared. Far worse was the death of his son William Harrison Tilley on 11 November. A brilliant career in the church was over and the father never recovered. Albert Smith wrote in sympathy, offering to have Tilley’s appointment renewed, or inviting him back into the fray.

Tilley had already decided to return to active politics with the next election. He had been in communication with Macdonald throughout his term, and had helped to organize Conservative clubs across the province. In October 1877 he met Macdonald and laid plans for the coming election. He finally became a “free man again” on 23 July 1878. Six days later he had a newspaper on the streets, the Saint John Daily Sun, and the fight was on. It would not be easy. Reconstruction following the fire, the completion of the Intercolonial Railway, the erection of Dorchester penitentiary, these had all insulated New Brunswick from the worst of the depression and thus blunted the Conservative attack on Mackenzie’s government. The return of a former lieutenant governor to politics became an issue, in addition, and then there was the National Policy, which the Conservatives were advocating and which meant higher taxes in New Brunswick. Tilley preferred to talk about a “readjustment of the tariff’ to protect jobs. He would stop working men from being “driven to a foreign country in order to gain employment.”

When Prime Minister Mackenzie and Minister of Finance Richard John Cartwright* arrived in Saint John on 22 August as part of that first whistle-stop campaign, Tilley was expected to lose the seat. They all gathered at the huge indoor skating rink for a public debate. Cartwright vilified Tilley and humiliated him, saying he would rather believe he “was the dupe than the accomplice, and that his faults should be attributed rather to the weakness of the head than to the wickedness of the heart.” The insults of those whom the Daily Sun called “carpet-baggers” from “Upper Canada” may have been crucial. Tilley won by nine votes. On 17 October he was again Canada’s minister of finance, with responsibility for the National Policy.

Tilley had about four months to prepare his budget. He knew more about tariffs and customs administration than any other politician in Canada at the time. He read John Maclean’s Protection and free trade (Montreal, 1867) and Jesse Beaufort Hurlbert’s Field and factory side by side; or how to establish and develop native industries (Montreal, 1870). Among the first of his team of experts hired to shape the policy were Hurlbert and Maclean. James Johnson, the chief commissioner of customs, whom Tilley had taken to Ottawa with him in 1867, was technically skilled, as was John Mortimer Courtney, the deputy minister of finance. Most important of all was Dr Edward Young, the Nova Scotian who had been chief of the United States Bureau of Statistics since 1870 and who had written the Special report on the customs-tariff legislation of the United States (1872 and 1877), the essential reference. Tilley and his group, in combination with members of parliament such as James Domville* of Kings County, N.B., and with businessmen such as George Gordon Dustan of Halifax, considered every aspect of the tariff. Acres of statistics were compiled to indicate the positive and negative implication of all possibilities, and they looked for a balance, including safeguards against rapaciousness.

When Tilley rose in the House of Commons on 14 March 1879 he was prepared. Canada, he said, was being used as a “slaughter-market” by the Americans and he would stop it with both tariffs and countervailing duties. He proposed “to select for a higher rate of duty those [items] that are manufactured, in the country, and to leave those that are not made in the country, or likely to be made in the country, – such as printed cottons – at a lower rate of duty.” The overall rate was raised, but there were specific duties and a lengthy free list. He wanted foreign investment to assist Canadian industry that would hire Canadians and keep them at home. He naturally turned to the Bible: “The time has arrived when we are to decide whether we will be simply hewers of wood and drawers of water . . . or will rise to the position, which, I believe Providence has destined us to occupy.”

Tilley was the architect of the National Policy, though others have claimed the title, and to the end of his life he never doubted its wisdom. He tinkered a bit with a rate here and there while he was minister of finance, but the changes were insignificant. “There was one good thing about the tariff in 1879,” Young wrote to Tilley in 1890. “It was well built, part corresponded to part as in a well planned building. Unlike nearly all U.S. tariff acts it did not require subsequent legislation to correct errors or omissions.”

Until he retired as minister in November 1885 Tilley was the policy’s guardian. In every budget speech he extolled its virtues, and except for the last year or so he could not be faulted. Old industries were rejuvenated and new ones sprang up across the country. He had a surplus of over $4,000,000 in 1882, just before the election, and he lowered the tariff on items such as tea and coffee. Industry was encouraged by addition to the free list of bulk zinc, tin, steel, and other materials. Over the next year, however, the economy began to turn downward, and the east was hit especially hard. It remained Tilley’s view that the National Policy saved Canada from the worst of the recession and stopped the Americans from again slaughtering the Canadian market.

By its very nature the ministry of finance involved Tilley in most of the functions of the government, especially since he chaired the Treasury Board. He made annual trips to England to raise money in the bond market. In the summer of 1879 he raised £3,000,000 in London, defended the National Policy before British critics, and participated in the negotiations to have a Canadian high commissioner appointed to London.

With the tariff policy established, the CPR became the dominant issue, and it would be far more controversial. Tilley supported the 1881 contract with a syndicate headed by Donald Alexander Smith*, James Jerome Hill*, and George Stephen*. He insisted that the line go through Canadian territory to free the country from American control, and he was pleased that private capitalists would undertake the construction and thus provide sound investment possibilities for Canadians. Tilley had been around enough railway contractors, however, to know that they bear watching, and he found the CPR group as devious as any. He discovered in 1881, for example, that Stephen was negotiating with Boston and Portland, Maine, as possible sites of the CPR’s eastern winter port, and despite denials those negotiations continued into 1884. To Tilley the only possible winter port was Saint John. Stephen and Tilley were to become intense adversaries as construction costs mounted. Stephen’s financial practices when he was president of the Bank of Montreal had already offended Tilley. Stephen thought he saw Tilley obstructing all legitimate requests for loans and guarantees, and he was not far from wrong. The requests arrived as the budget surplus disappeared in 1883. With deficits unavoidable, Tilley did not believe the country could afford the risks that Stephen demanded, nor did he believe it should abandon all other endeavours in order to feed the CPR. Moreover, he simply did not trust Stephen. He grew increasingly isolated in the cabinet, which became obsessed with the early completion of the railway despite the fact that the process was neither giving jobs to Canadians nor assisting Canadian industry.

Tilley had been especially robust during the 1882 election and had fought a successful contest, speaking widely and often. The following winter, however, he was frequently not well, and his ill health continued. By April 1885 his condition was serious. Whatever his physical disabilities, he remained on top of finance and his other responsibilities. His 1885 budget was considered one of his best, and when Tupper, by then the high commissioner in London, recommended a totally unacceptable plan for a government loan, Macdonald had to send Tilley to settle the matter. He arrived on 23 May and by 1 June he and Sir John Rose, now a London financier, had everything under control.

Tilley went to Sir Henry Thompson while in London, his third specialist in three years. Thompson discovered a kidney stone that was removed in a painful operation, and he ordered Tilley to retire. Though evidently weak and in pain, Tilley attended the last day of the sitting of the Canadian parliament on 20 July. He wrote to Macdonald that day, “You need, and must have young blood.” Tilley then left Ottawa for New Brunswick and the sea air of St Andrews, where he had a summer home.

As he matured, Samuel Leonard Tilley had risen above the narrowness of his early disposition and become a highly successful pragmatic politician, a classic trimmer. During his active career he never achieved wide popularity. There was a streak of self-righteous stubbornness, and he had neither Macdonald’s flair nor his earthiness, though he did look after his friends perhaps too well. None the less, because his political capacities were accompanied by superior financial skills he had emerged as the essential man in New Brunswick before confederation and come close to achieving this rank again in Canada after 1878.

Tilley’s public career was to have one final chapter. On 11 November Macdonald had him appointed lieutenant governor of the province for a second term, one that lasted until the fall of 1893. He was finally regarded as a distinguished native son, even by his oldest enemies, and Macdonald continued to consult him for a few months, but younger men were taking over. Tilley did become involved with the Imperial Federation League in an effort to counterbalance notions of commercial union with the United States. Macdonald’s death in June 1891 cut deeply. Tilley was replaced as lieutenant governor in 1893 by John Boyd, a neighbour and friend since the 1850s, and Boyd’s death on 4 December the same year hurt even more. As the Conservative party struggled through its leaders in the 1890s Tilley watched intently. He had great hopes for Sir John Sparrow David Thompson, and became very agitated by his death on 12 Dec. 1894 and by the disintegration of the party over the Manitoba school issue. In April 1896 he wrote a celebrated defence of the remedial legislation, which was published in the Daily Sun and widely reprinted. As Prime Minister Tupper faced his June election Tilley sensed that he could not win. Early in June Tilley cut his foot while at the Rothesay summer home he had bought. By 11 June blood-poisoning had spread through his system. On 25 June he was gone, aged 78. Tupper had lost his election two days earlier. It was said that Tilley did not know of that defeat, but he knew the end had come.

[Except for a semi-authorized biography by James Hannay*, The life and times of Sir Leonard Tilley, being a political history of New Brunswick for the past seventy years (Saint John, N.B., 1897), little has been written on Tilley. Hannay’s study was begun with his approval about 1890, but offers few insights into its subject, who was to become stigmatized as a colourless druggist and temperance advocate. The appearance of the Tilley papers in the 1950s and 1960s combined with studies in both confederation and regional history renewed interest in the man. Tilley had saved his papers carefully from the 1850s until his death in 1896, but they had subsequently been scattered and forgotten. The N.B. Museum acquired the largest block (Tilley family papers) in 1958, and the NA received another substantial segment (MG 27, I, D15) ten years later, including the letter-books for Tilley’s years as minister of finance. Together these holdings represent the largest collection for the period prior to 1867 of any of the fathers of confederation except Macdonald. Several other collections at the NA are rich in Tilley materials, especially those of Howe (MG 24, B29), Macdonald (MG 26, A), Galt (MG 27, I, D8), Tupper (MG 26, F), and Brown (MG 24, B40).

For the pre-confederation years MacNutt, New Brunswick, is the most valuable of the modern secondary sources, though he did not have access to the Tilley papers and maintains an imperious Colonial Office view of provincial politicians. J. K. Chapman’s excellent study, The career of Arthur Hamilton Gordon, first Lord Stanmore, 1829–1912 (Toronto, 1964), is in the same mould. Waite, Life and times of confederation, is the best survey with the most acute insights into Tilley. For Tilley’s post-confederation years secondary sources are far less satisfactory, though Waite, Canada, 1874–96, might be consulted. Creighton, Macdonald, young politician and Macdonald, old chieftain, include some references to Tilley. The most recent study is C. M. Wallace, “Sir Leonard Tilley, a political biography” (phd thesis, Univ. of Alta., Edmonton, 1972). c.m.w.]

N.B. Museum, James Brown journal (photocopy); J. W. Lawrence papers, “Some reminiscences, Hon. Sir Leonard Tilley and J. W. Lawrence, 1835–1885” (A313); J. C. Webster papers, packet 25 (A. R. McClelan, corr.). PANB, RG 2, RS6, A, 1854–67; RG 29. PRO, CO 188; CO 189. UNBL, MG H6; MG H 10; MG H12a; MG H82. Can., House of Commons, Debates, 1867–85; Parl., Sessional papers, 1867–85. G. E. Fenety, Political notes and observations . . . (Fredericton, 1867). Lawrence, Judges of N.B. (Stockton and Raymond). J. [A.] Macdonald, Correspondence of Sir John Macdonald . . . , ed. Joseph Pope (Toronto, 1921). N.B., House of Assembly, Journal, 1850–68; Synoptic report of the proc., 1854–68; Legislative Council, Journal, 1860–67. Joseph Pope, Memoirs of the Right Honourable Sir John Alexander Macdonald, G.C.B., first prime minister of the Dominion of Canada (2v., Ottawa, [1894]). Stewart, Story of the great fire. Charles Tupper, Recollections of sixty years in Canada (Toronto, 1914). E. W. Watkin, Canada and the States: recollections, 1851 to 1886 (London and New York, [1887]). Daily Sun (Saint John), 1878–87, later St. John Daily Sun, 1887–96. Daily Telegraph (Saint John), 1864–80. Globe, 1864–85. Head Quarters (Fredericton), 1849–68. Mail (Toronto), 1872–80, later Toronto Daily Mail, 1880–85. Morning Freeman (Saint John), 1851–75. Morning News (Saint John), 1840–84. New-Brunswick Courier, 1831–62. New Brunswick Reporter and Fredericton Advertiser, 1854–85. Ottawa Daily Citizen, 1867–85. Saint John Globe, 1866–96. Appletons’ cyclopædia (Wilson et al.). Canadian biog. dict., vol.2. CPC, 1867–85. Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose and Charlesworth), vol.1. Dent, Canadian portrait gallery. DNB. Dominion annual reg., 1878–85. William Notman and [J.] F. Taylor, Portraits of British Americans, with biographical sketches (3v., Montreal, 1865–68). Standard dict. of Canadian biog. (Roberts and Tunnell), vol.2. T. W. Acheson, Saint John: the making of a colonial urban community (Toronto, 1985). Baker, Timothy Warren Anglin. Gordon Blake, Customs administration in Canada: an essay in tariff technology (Toronto, 1957). Hannay, Hist. of N.B. D. G. G. Kerr, Sir Edmund Head, a scholarly governor (Toronto, 1954). W. M. Whitelaw, The Maritimes and Canada before confederation (Toronto, 1934; repr. 1966).

Cite This Article

C. M. Wallace, “TILLEY, Sir SAMUEL LEONARD,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 6, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/tilley_samuel_leonard_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/tilley_samuel_leonard_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | C. M. Wallace |

| Title of Article: | TILLEY, Sir SAMUEL LEONARD |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | December 6, 2025 |