Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

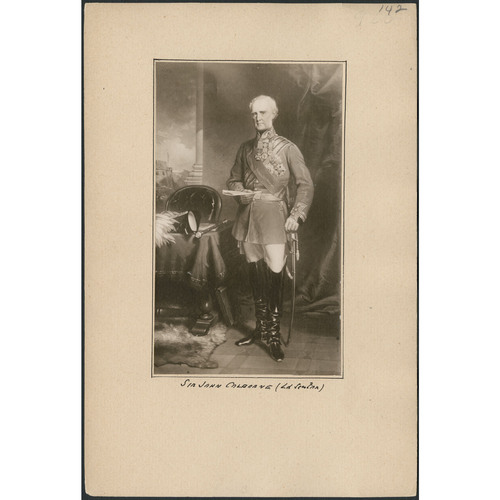

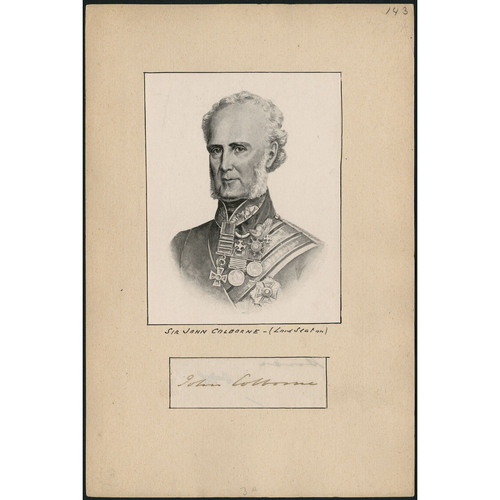

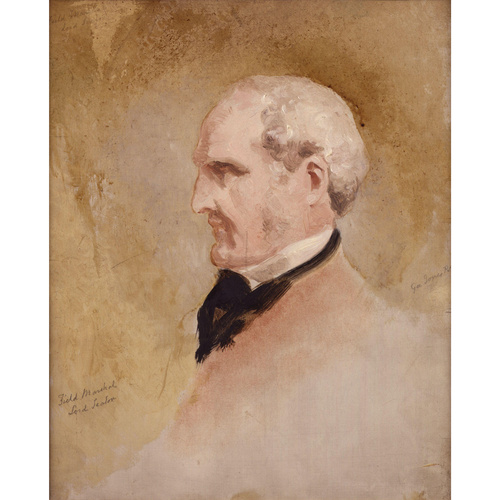

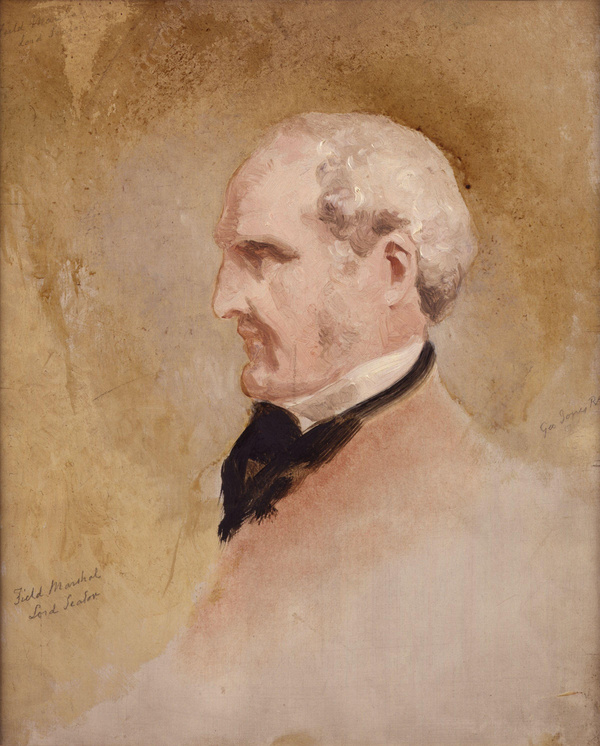

COLBORNE, JOHN, 1st Baron SEATON, soldier and colonial administrator; b. 16 Feb. 1778 at Lyndhurst, Hampshire, England, the only son of Samuel Colborne and Cordelia Anne Garstin; d. 17 April 1863 in Torquay, Devonshire, England.

An orphan at age 13, John Colborne was educated at Christ’s Hospital, London, and Winchester College. He entered the army as an ensign in the 20th Regiment in 1794, winning his subsequent promotions to field marshal without purchase. Though not aggressive, he was concerned that his achievements should be recognized, and on occasion successfully drew attention to an earned but unawarded promotion.

Promoted captain-lieutenant in 1799, he saw active service at Helder (Netherlands), and as captain in Egypt, Malta, and Sicily. In 1806 he became military secretary to General Henry Edward Fox, commander in Sicily and the Mediterranean. He was promoted major in 1808 by Sir John Moore, who made him his military secretary. He accompanied Moore to Sweden and Portugal; at Coruña (Spain) Moore’s dying request was that Colborne be gazetted lieutenant-colonel. Between 1809 and 1811 he exchanged units twice before joining his long-time regiment, the 52nd Regiment of Oxfordshire Light Infantry, one of the famous three forming the Light Brigade.

After service under the Duke of Wellington in the Iberian Peninsula at Ocaña, Busaco, and Albuera, he assumed command of the 52nd and in January 1812 was severely wounded in leading the attack at Ciudad Rodrigo. Though permanently disabled in one arm, he returned to active service in July 1813, assuming temporary brigade command for the battles of the Nivelle and the Nive in the Pyrenees. He again commanded the 52nd early in 1814 at Orthez and Toulouse (France). With the peace he was promoted colonel in 1814, becoming one of the first to receive a kcb in January 1815. He meantime assumed new duties as aide-de-camp to the Prince Regent, and military secretary to the Prince of Orange, commander of Britain’s forces in the Netherlands.

One of the most significant events in Colborne’s career took place in 1815, following Napoleon’s escape from Elba. Ordered to Belgium, the 52nd formed part of Major-General Sir Frederick Adam’s Light Brigade, charged with maintaining communications on the extreme right of the British line at Waterloo. This position confronted a substantial part of Napoleon’s famed Imperial Guard, and was designed to prevent any move to bend the British line. When, on 19 June 1815, the Imperial Guard was observed to be preparing a northern charge in column through the allied lines, the Light Brigade was moved forward and assumed a flanking position facing east to direct its fire into the side of the advancing French column. When the moment came, however, and after the brigade had discharged its early volleys, Colborne, acting without authority but with boldness and brilliant initiative, swung the 52nd out of line and led it in a daring charge that immediately swept back the Imperial Guard in a rout. As the Guard fell back in confusion, the rest of the French army collapsed in complete disarray along the road to Charleroi. Colborne’s bold stroke has been credited with assuring victory at Waterloo, although Wellington never acknowledged its decisiveness. Nonetheless, the “colonel of the 52nd” was widely acclaimed, and was awarded honours by England, Austria, and Portugal.

In the long peace that followed, Colborne remained strongly attached to the military, but he also undertook a succession of civil appointments. In these posts much of his success derived from his distinguished military reputation and great character, but much also was owing to the charm and graciousness of his wife, Elizabeth, daughter of James Yonge, rector of Newton Ferrers, Devonshire. From their marriage in 1813, Colborne acquired a large family, including two sons destined to become generals, and a household notable for its warmth, simplicity, and generosity. It was an important balancing asset for a civil governor whose military bearing and natural reserve were unrelieved by a quick, almost impetuous manner. But behind his abruptness, a dutiful, disciplined nature had been moulded by several acute bereavements, by rigorous training, and above all by a deep religious conviction. The Anglican faith surrounded Colborne in his step-father, Thomas Bargus, his father-in-law, and brother-in-law, all of them Anglican clergy; in his devout wife; and in his friends, such as Henry Phillpotts, bishop of Exeter, whose brother George was Colborne’s aide-de-camp in Upper Canada. As he advised his son James, attend “to the study of Christ and study of yourself, which is the wisest preparative for all that may happen to us.” Beyond its implications for personal conduct, religion also served for him as a guarantor of order and hierarchy in society and government. His own simplicity and lack of display, however, rescued him from the charge of sanctimoniousness.

Colborne’s promotion to major-general in 1825, and his tenure as lieutenant governor of Guernsey from 1821 to 1828, strengthened his reputation for effective administration and popular leadership. In many respects he served his apprenticeship in Guernsey for his role as Upper Canada’s ablest governor. There Colborne built on the work of Sir John Doyle, who had achieved major fiscal, communications, and harbour improvements. Following the post-war depression and the bitter contest between Guernsey and Whitehall over proposals to revise the Corn Laws, Colborne sought to restore the islanders’ loyalty. His appointment happily coincided with that of a new chief civic magistrate, Daniel De Lisle Brock, a distinguished Guernsey landowner and brother of Sir Isaac Brock*, whose military and civil duties Colborne would assume seven years later. A second Guernsey man, Major-General Sir Thomas Saumarez, had served as commandant at Halifax and president of the Council and commander-in-chief of New Brunswick during the War of 1812. Thus Colborne could find in Guernsey’s tiny society both inspiration and interest in the affairs of Britain’s North American colonies.

The Colborne-Brock administration quickly re-established public confidence with impressive additions to the road system, indirect taxation for general improvements, increases in regular communication with England, the introduction of a first iron foundry, the construction of new quays and public markets, a reversal of the pattern of steady emigration, and a general increase in the value of agricultural lands and urban facilities. The pattern would be repeated by Colborne in Upper Canada. In three particular ventures, his experience had even closer parallels. First, Colborne counteracted a great rise in the strength of “sectaries,” chiefly Wesleyan Methodists, by strengthening the establishment of the Church of England; second, with Brock’s help, he laid the ground for removing the tithing system which encouraged strong anti-Anglican resentment; third, he re-established a boys’ preparatory school, Elizabeth College, to strengthen education, the state religion, and a governing élite.

On 14 Aug. 1828 Colborne was gazetted lieutenant governor of Upper Canada, succeeding Sir Peregrine Maitland*, and arrived at York (Toronto) on 3 November. His was not to be an easy governorship: Maitland’s imperious conduct and his wife’s social pretentions had helped turn an early, natural, conservative leadership into an unnatural Tory establishment. This Family Compact had become increasingly resented by rural agrarian radicals, urban malcontents such as William Lyon Mackenzie and Francis Collins*, religious nonconformists such as Egerton Ryerson*, American-born and Jacksonian sympathizers such as Marshall Spring Bidwell*, and moderates such as Robert* and William Warren Baldwin*, whose preference for conservative measures was qualified by disquiet over the ruling caste’s arrogance. Colborne’s arrival prompted unusual expectations of redress of grievances and of a liberal conduct that must strain his natural conservatism and soldierly concepts of constitutional limitation and duty. His military background had prepared him to take a hard line on constitutional responsibility and sovereign authority. He would not be a party to a direct colonial challenge to prevailing constitutional forms. His concern for Guernsey’s interests, however, had prepared him for some of Upper Canada’s challenges. Shrewd changes in the Legislative Council’s composition, decentralization from York, independence from cliques of advisers, and executive enterprise and efficiency might serve as substitutes for root-and-branch constitutional reforms.

Colborne’s new capital was only one-seventh the size of his last, and his style would be appropriate to the village status of little York with its 2,200 inhabitants. The simplicity of his manner and the lack of ostentation of his household soon set many minds at rest. Pressed to intervene in the causes célèbres of Judge John Walpole Willis* and the Francis Collins libel trial, which had been turned to good account by the radicals, he stood firm with the ordinary processes of the law and of appeal, and exerted a modest, successful pressure to have these issues resolved sympathetically by the imperial authorities.

But Colborne had arrived in York soon after the most exciting election in the colony’s history, in which the Reformers had won a resounding victory. His capital, however, had upheld the Tory candidate and leader of the Compact, John Beverley Robinson. Plainly, Colborne was caught between fires. On the one hand were the over one-third of York householders with government connections, the prospering merchants, and purveyors to the Compact, and across the province the sub-branches of Compact support shored up by a disquieted but still moderate rural populace. But Colborne could recognize, too, a party of legitimate protest led by men like Bidwell, John Rolph, and the Baldwins, and abetted by the extravagant exaggerations of others, of whom Mackenzie was among the more responsible. Moreover, his position was further compromised by the ambiguity of the situation in Britain. A select committee of the British House of Commons in the fall of 1828 had sharply criticized the Legislative Council’s hold over the province, the claims of the Church of England for special consideration, and Archdeacon John Strachan’s cherished plans for an Anglican university. But Colborne’s old commander, the Duke of Wellington, was now prime minister, and it was doubtful whether the liberalism of the Commons’ declaration would ever influence the Iron Duke. Colborne himself declared that the report had “done much harm in both Provinces, by furnishing the disaffected with arguments that suit their views. . . .”

Faced with an assembly-elect anxious to convene and to begin its Augean tasks, Colborne employed caution, conciliation, and affability to ease a difficult situation. Far from being made captive by the prejudices of the Family Compact, he brought his own convictions from his previous governorship. Purposely he avoided close association with the Compact’s leaders, notably with Strachan, whose “Ecclesiastical Chart” and university plans had probably ensured the Reformers’ 1828 electoral victory. Robinson’s elevation to the chief justiceship in July 1829 also eased his task by reducing Robinson’s room to manoeuvre openly as a principal Compact strategist and by furnishing the opportunity to call a York by-election, allowing the moderate Robert Baldwin to win an assembly seat. When the Reformers challenged that the speaker, not the governor, must issue an election writ, Colborne graciously acceded, and still another election in 1829 returned Baldwin.

Judgements of Colborne’s early performance led to growing confidence in him. The 1829–30 assembly passed much sound legislation supporting road construction, commercial improvements, relief from War of 1812 losses, and the encouragement of agricultural societies – enterprises with which Colborne had been closely associated in Guernsey.

In other matters, however, things proceeded less harmoniously. In the 1829 session Mackenzie introduced his famous 31 grievances and resolutions, several of which challenged Colborne to declare himself on basic constitutional issues such as judicial independence, church establishment, local control of the province’s internal affairs, and the composition and role of the Executive and Legislative councils. Sir John would not champion constitutional positions that he felt must properly be determined in England; but he did transmit his opinion to the imperial authorities that the constitution was unsatisfactory and that Whitehall should investigate. Colborne treated the assembly as a debating group, and expressed concern over the Legislative Council’s frequent intransigence in blocking strongly supported assembly measures, but he was not ready to strengthen the assembly itself. Partly, his reluctance arose from his interpretation of his constitutional position, but part may also be ascribed to the province’s general prosperity. This economic health provided such indirect revenue that during his first years in Upper Canada Colborne did not have to ask the assembly to vote supplies, a circumstance strongly qualifying his view of its role and powers.

Another source of potential trouble rested in religion. Despite Colborne’s early attempts to remain aloof from, indeed to criticize, Strachan’s active political role, he was not one to dissemble about his own religious convictions. His ideas of religious organization were as orthodox as his canons of military conduct. “Sectaries” were guerillas; the denominations must be preserved and enlarged. In Guernsey he had witnessed a remarkable growth in the number of sects, and particularly in the number of Wesleyans, but a contemporary account held that their introduction had invigorated the Anglican clergy. In Upper Canada Colborne was alarmed at the Methodists’ great increase in strength, at the face that the strong Reform assembly of 1828 was often called the “saddlebag assembly,” and that in 1829 the Methodists were gaining enormous support with their hard-hitting new journal, the Christian Guardian. Moreover, the editor, Egerton Ryerson, was clearly sympathetic with many of the causes of Mackenzie. Colborne would inevitably confront the Methodists, but his experience in Guernsey led him to seek better ways than Strachan’s to support his church’s establishment.

The early evidences of the new governor’s independence, rectitude, and conservatism soon disarmed all but extremists on both sides. Moreover, he indicated his readiness to effect changes in the Legislative Council’s composition by appointing new members from outside the York clique, even if he would not admit his own constitutional competence to change its functions. Such carefully considered accommodation had its effect in the election forced upon the province by George IV’s death in 1830. Having achieved much at the assembly’s committee level but little cohesion as party men, the Reformers lost heavily, holding only 17 of 51 seats. Colborne’s reputation brought moderates and conservatives into a new and sympathetic assembly. For the remainder of his term, despite Mackenzie’s increasing radicalism, Colborne displayed considerable initiative and leadership. Often ignoring the squabbling of Reformers and radicals, he single-mindedly pursued his own “good works.” That he also failed to inform his superiors at the Colonial Office of many of these activities was partly a consequence of his dedication; partly, too, a result of having too many masters – six colonial secretaries in the nine years of his incumbency.

Colborne concentrated on making practical improvements in communications, roads, bridges, and market facilities which were beneficial to a sparsely settled colony. He was also determined to increase the size and improve the quality of the British community in Upper Canada through immigration and education. Government should provide assistance to needy immigrants, and expect services in clearing land and improving roads in return; the result would be early employment and sustained morale. When York’s expansion was blocked by a military reserve, the governor relocated the reserve; to improve communications he personally paid £1,175 to repair the Don and Humber bridges, challenging the assembly to reimburse him.

Town improvement was important, but rural growth should also be encouraged. Reducing isolation would attract more people and more capital. Colborne’s strategy was to concentrate upon a few townships, building well initially to encourage an early maturity and solvency. At Cobourg, Peterborough, and London he deployed new agencies for the settlement of immigrants, and encouraged the establishment of local immigrant societies. In 1829 he introduced the so-called Ops Township experiment, later extending it to Douro, Oro, and Dummer townships, up the Ottawa valley, and in the southwest between Colonel Thomas Talbot*’s lands and the Huron Tract. According to the experiment’s plan, access roads were built to new settlements, temporary shelters in the new districts were provided, and a series of immigration agencies was established at Montreal, Prescott, and Cobourg. Supplies were sold cheaply by government agents until the newcomers were well settled. Indigents who had faithfully effected their own improvements but who lacked cash had their payments delayed or were given employment artificially stimulated to enable them to pay. Reformers in the assembly objected to the high costs of the programme of assisted settlement and resented the executive’s unilateral use of public funds; Conservatives resented the encouragement given to indigent immigrants who, they were convinced, would soon swell the ranks of the “democrats.” But both the assembly and the Colonial Office were expected to support Colborne’s ambitious projects – often after they had been instituted without prior consultation.

Colborne’s colonizing purpose was two-fold: to attract more of the masses of emigrants leaving England and thereby to reduce the proportion of American immigration and influence in Upper Canada. As late as 1833 he considered establishing a western subdivision of the province centred in London, in an effort to combat the forces of “republicanism” in the west. Measured by the increased number of immigrants and reduced re-emigration to the United States, he was highly successful. Moreover, partly because of his leadership in meeting the cholera epidemic of 1832, York became a resort for refugees from other localities seeking better preventive measures and treatment. Consequently, the high rate of immigration persisted from 1830 to 1833, the province’s population growing by 50 per cent, and York’s better than doubling.

With so many new English settlers and such a record of smooth adjustment, Colborne correctly predicted by 1834 that the province’s political stability, by which he meant a conservative and industrious electorate, was assured. With his further programme of attracting to rural Upper Canada a class of gentlemen farmers from the ranks of British doctors, clergy, and half-pay officers, he may be excused to some degree if he did not draw to Whitehall’s attention the intemperate criticisms of Mackenzie’s minority. He believed that the best military and political policy was to ensure a large, secure population who would eschew grievance-mongering and rally to the defence of their interests. The fine line between Colborne’s high-minded policy and the Compact’s narrow pursuit of its own interests, however, was not always clear, and in his religious policies he invited disaster.

Colborne had been unwilling in 1828 to accept Strachan’s proposal for a university in an undeveloped colony. Nor could he respect Strachan’s tactics in strengthening the bond between his church and the interests of society. Consequently, he withheld support from King’s College, turning instead to his Guernsey experience by creating first a classical English preparatory school, Upper Canada College, which was to produce an educated student body ready for university training. Colborne valued his own schooling, and throughout his life he pursued the classics, mathematics, rhetoric, history, and modern languages. Overwhelming his council and his Whitehall superiors with his organizational zeal, he brought the school into operation with a half-dozen highly qualified masters such as Joseph Hemington Harris* imported from the ranks of the English clergy. That the Methodists had been laying plans for an Upper Canada Academy was not lost on Sir John, but his pupils would be the sons of “gentlemen.” Colborne’s diversion of public school reserves funds and university money to his new school guaranteed opposition from all sides.

The second evidence of Colborne’s fatal obstinacy in religious matters is his means of securing education and improved conditions for the Indians. Despairing of the Church of England’s efforts, ironically he turned to the mission-minded Methodists. But in a series of secretive negotiations, Colborne encouraged the British Wesleyan leaders in preference to Ryerson’s Canadian Episcopals, thus raising once again the old cry of Maitland’s day that the Canadian Methodists were disloyal. Although ostensibly the British Wesleyans were encouraged to return for the sake of the Indian missions, their coming would also fulfil Colborne’s goals of strengthening the anti-American and anti-republican spirit of Upper Canada and of challenging “natural” conservatives like Ryerson to loosen their radical ties and moderate their opposition to church establishment. The divisiveness of his tactics, however, undermined his conservative, unifying purpose.

The governor’s most controversial act was his designation of rectory lands for the Church of England, an action in train since 1831 but taken only on the eve of his departure from Upper Canada in January 1836. Justification for designating 15,000 acres of the clergy reserves and another 6,600 acres of crown lands specifically to the endowment of 44 Anglican rectories across the province rested in the 1791 Constitutional Act and in the ambiguity of instructions from various colonial secretaries, but Colborne’s timing was extraordinarily inappropriate. He successfully opposed his council’s intent to add a spiritual jurisdiction to a comprehensive land endowment – and thus to affirm a formal establishment of the Church of England – but such distinctions were lost on radicals, Reformers, and many moderates. The rectories crisis undoubtedly precipitated the unrest of 1837, and was among the factors which had prompted the colonial secretary, Lord Glenelg, to recall Colborne early in 1836.

Arriving in New York in late May 1836, however, Colborne unexpectedly received a dispatch from Glenelg appointing him commander-in-chief of the forces in the Canadas. Colborne felt that Glenelg appointed him to the post to indicate his respect for him despite his having had to remove him from Upper Canada and because he was an experienced military leader whose presence in Lower Canada might encourage moderation and discourage civil disorder. Colborne’s knowledge of Lower Canada was probably confined to the impressions he had gathered while staying with members of the English speaking community in Montreal from February to May 1836.

Dutifully, Colborne journeyed to Montreal, despite his private criticisms of Governor General Lord Gosford [Acheson*] for bringing a regiment to Lower Canada from Halifax, a move Colborne thought unnecessary and likely to cause alarm. During the summer of 1837 he did not anticipate a rebellion, believing instead that the public meetings addressed by Louis-Joseph Papineau*, though “of a very seditious character,” would “produce little effect here.” Nonetheless, by October he had fortified Quebec, ordered military supplies, and recruited troops to be in readiness for a possible uprising. Throughout the fall the political situation worsened; on 13 November Colborne’s wife wrote that “the whole country has . . . apparently changed its nature in the short space of the last fortnight, and become interested in a revolution.” With the outbreak of rebellion on 16 November, Colborne quickly marshalled the regular and militia forces, even drawing on Upper Canada’s regulars, so confident was he of his earlier preparations in the upper province. Snow-shoes and 100 sleighs were prepared for the troops; £100 was spent to shut Quebec’s long-unused and rusted gates; veterans of Colborne’s 52nd turned out enthusiastically; and Colborne personally led 2,000 men, with artillery, against the rebels. By late December 1837 the insurrection had been put down.

Colborne, however, could not look forward to an early retirement, for meantime Governor General Gosford had abruptly resigned, and it would fall to Sir John as administrator to deal with the late rebels. Colborne preferred that the rebels, having been dealt with firmly in the field, should be treated generously in the courts. The decision, however, would not rest with him. In late February 1838, word arrived that Whitehall further proposed that martial law should end, the constitution be suspended, a special council established, and a special commission under Lord Durham [Lambton*] sent to Canada to govern and to prepare recommendations for the future government of the Canadas. On 29 May 1838 Durham landed at Quebec and assumed authority.

Colborne’s early relations with the new governor general were good, and his preference for firm but humane treatment of the late rebels influenced Durham’s decision to banish the leaders to Bermuda. But in other matters they differed. Sir John was sceptical of Durham’s proposal for union of the two provinces because he felt it would encourage the importation of Lower Canada’s serious troubles into the upper province. He also saw the union as simply a means of politically overwhelming the French Canadians and thereby adding the alarming prospect of assimilation to their existing unrest. Colborne was even less sympathetic with the measure of colonial self-government, however limited, that Durham proposed for the new union. Moreover, his confidence in Durham’s judgement grew weaker on longer acquaintance. Despite his anxiety to resign – and his wish to gain the governorship of the Ionian Islands – Colborne yielded to Glenelg’s request that he remain because he enjoyed the confidence “of all persons . . . to a degree to which it is clear no other could attain.” Promoted lieutenant-general, his services were urgently needed by fall when, first, Lord Durham abruptly resigned his special commission and returned home, and, second, fresh unrest threatened in the lower province. During November 1838 Colborne was engaged in putting down even more effectively and swiftly a new insurrection. In mid December he was gazetted governor general amidst a series of courts-martial dealing severely with the second group of rebels. Colborne believed that an extended period of firm, semi-military, but enlightened rule would defuse the situation and provide Lower Canada with time to readjust to British colonial institutions. He did approve of Durham’s resignation because it would allow him to extend this period of firm readjustment, and he agreed with Durham that it was necessary to teach the British authorities some of the realities of the Canadian situation.

Because of his handling of the rebellion and its aftermath, however, Colborne became known to Québecois as “le Vieux Brulôt,” a symbol of brutality, of Anglo-Saxon fanaticism, and of anti-Catholicism. Historians from François-Xavier Garneau and Thomas Chapais* to Lionel Groulx* have condemned him for the seeming ruthlessness of his part in crushing the Lower Canadian rebellions. It was Colborne’s conviction, however, that Gosford’s equivocal and dilatory tactics had encouraged the growth of a rebellious population. Moreover, although on several occasions the rebels’ numbers would melt away overnight before the actual engagements, Colborne’s intelligence had reported substantial numbers of armed and concentrated dissidents. Having been recalled from New York as a military commander, he had made appropriate preparations, fatefully employing numbers of local English speaking volunteers in the expectation of meeting larger forces than proved in the event. The volunteers, and many of the British regulars, it was concluded by contemporaries such as Lieutenant E. Montagu Davenport and historians such as Robert Christie* and Chester New*, were enflamed by the guerilla tactics of the Patriotes, by the sadistic murder of a courier, Lieutenant George Weir, and by the fatigue and frustrations of operations conducted in bitter weather under exhausting conditions. The disruption of communication between Colborne’s headquarters and his two field commanders, lieutenant-colonels Charles Stephen Gore and George Augustus Wetherall, further complicated operations and left great discretion and responsibility with those officers for the conduct of their men. The rebels’ resort to churches, convents, and strongly constructed stone houses as points of defence forced the use of artillery and of dangerous frontal attacks by the government’s forces. All of these circumstances contributed to unauthorized, even forbidden, pillage in the aftermath of a bitter campaign.

How much Colborne was informed of the troops’ excessive behaviour is problematical. Even at the height of his earlier military successes he had been known for his efficiency, not for ruthlessness, and since 1821 he had devoted himself to the arts of civil administration. Perhaps with better field communication he might have put firmer constraints upon his men and his commanders. Some evidence of his civil concern for French Canadians may rest in his resentment that Charles Poulett Thomson*, whom he considered too much the genial diplomat to contain unrest and enlighten the British authorities on the serious racial and political problems Canada faced, was to be given the mandate to serve as governor in the days following the rebellions. Colborne had apparently not conceived such an animosity toward the French Canadians that he could not in good conscience contemplate serving as governor in a period of firm but humane recovery from the troubles of 1837–38.

On learning that Whitehall proposed sending yet another viceroy as governor general, but wished to retain his services as commander-in-chief, Colborne’s patience broke. The idea of asking him to remain under Thomson, when the latter’s policy of conciliation and moderation must make Colborne’s actions appear even more Draconian, determined him to leave at the earliest opportunity. Colborne believed the new governor would have been greatly assisted had union come about under his own superintendence, and he would not “stand behind his amiable, conciliating, propitiating successor.” At Quebec, on 19 Oct. 1839, Sir John yielded office to Thomson, and was invested with the gcb. Several days later, aboard the frigate Pique at Montreal, someone rallied a large crowd of well-wishers with the cry, “One cheer more for the colonel of the 52nd”; on 23 October Sir John left Quebec and Canada.

In England Colborne was widely recognized and rewarded for his distinguished military career and his 16 years of service in Guernsey and Canada, being named a privy councillor, receiving a pension of £2,000 annually, and being elevated to the peerage as Lord Seaton of Seaton, Devonshire, on 14 Dec. 1839. He continued to take an interest in Canadian affairs from the House of Lords. In 1840 he combined with Lord Gosford to oppose Thomson’s proposed union; simultaneously, he allied with Lord Ripon (formerly Lord Goderich) and with Henry Phillpotts to try to stop Thomson’s clergy reserves bill; in 1850 and 1853 he combined with the Duke of Argyll, the Church of Scotland’s senior advocate in the Lords, to try to stop legislation enabling the Canadian parliament to dispose of the clergy reserves, which would lead to secularization. But these moves were mostly in vain, and his activities were already centred elsewhere.

From 1843, when he was made a gcmg, until 1849, he served as lord high commissioner of the Ionian Islands. In 1854 he was promoted general, and named colonel of the 2nd Life Guards. From 1855 to 1860 he served in Ireland as commander of the forces and as a privy councillor, as well as attending to his own considerable estates in County Kildare. In 1860, on his retirement, he was raised to England’s highest military rank and honour, field marshal. After a short period of failing health, however, he died, aged 85, at Torquay.

MTCL, Robert Baldwin papers. PAC, MG 24, A25; A40; B11; B18; RG 5, A1, 90–170; RG 7, G1, 69, 74–75. PAO, Macaulay (John) papers; Mackenzie-Lindsey papers; Robinson (John Beverley) papers; Strachan (John) papers. PRO, CO 42/388–427; 43/42–45. U.C., House of Assembly, Journals, 1828–36. Dent, Canadian portrait gallery, III. DNB. D. B. Read, The lieutenant-governors of Upper Canada and Ontario, 1792–1899 (Toronto, 1900). H. I. Cowan, British emigration to British North America; the first hundred years (Toronto, 1961). Craig, Upper Canada. Jonathan Duncan, The history of Guernsey; with occasional notices of Jersey, Alderney, and Sark, and biographical sketches (London, 1841). Aileen Dunham, Political unrest in Upper Canada, 1815–1836 (London, 1927; repr. Toronto, 1963). J. W. Fortescue, History of the British army (13v., London and New York, 1899–1930). Gates, Land policies of U.C. William Leeke, The history of Lord Seaton’s regiment (the 52nd Light Infantry) at the battle of Waterloo . . . (2v., London, 1866). J. D. Purdy, “John Strachan and education in Canada, 1800–1851” (unpublished phd thesis, University of Toronto, 1962). G. C. M. Smith, The life of John Colborne, Field-Marshal Lord Seaton, G.C.B., G.C.H., G.C.M.G., K.T.S., K.St.G., K.M.T. . . . (London, 1903). Wilson, Clergy reserves of U.C. G. C. Patterson, “Land settlement in Upper Canada, 1783–1840,” in Ont., Dept. of Archives, Report (Toronto), 1920. Helen Taft Manning, “The colonial policy of the Whig ministers, 1830–37,” CHR, XXXIII (1952), 203–36, 341–68.

Cite This Article

Alan Wilson, “COLBORNE, JOHN, 1st Baron SEATON,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 15, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/colborne_john_9E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/colborne_john_9E.html |

| Author of Article: | Alan Wilson |

| Title of Article: | COLBORNE, JOHN, 1st Baron SEATON |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1976 |

| Year of revision: | 1976 |

| Access Date: | February 15, 2026 |