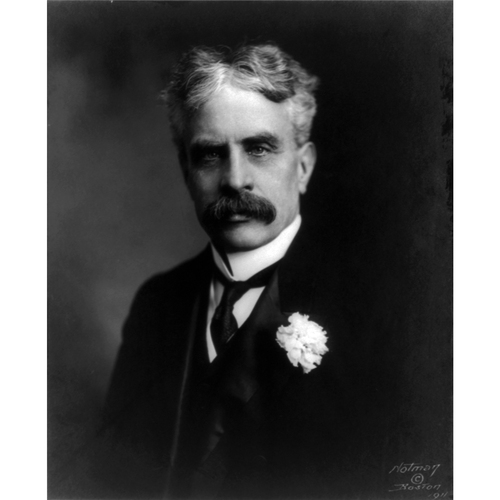

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

BORDEN, Sir ROBERT LAIRD, lawyer and politician; b. 26 June 1854 in Grand Pré, N.S., first child of Andrew Borden and Eunice Jane Laird; m. 25 Sept. 1889 Laura Bond (d. 8 Sept. 1940) in Halifax; they had no children; d. 10 June 1937 in Ottawa.

Robert Laird Borden’s paternal ancestor Richard Borden left Headcorn, England, in 1638 to settle in Portsmouth, R.I. More than a century later, after the Acadians had been expelled from Nova Scotia in 1755 [see Charles Lawrence*], Richard’s great-grandson Samuel Borden, a landowner and surveyor in New Bedford, Mass., was commissioned by the Nova Scotia government to survey the vacated lands and lay out plots for New Englanders intending to settle there. In 1764 Samuel received a parcel of land in Cornwallis for his work, but he returned to New Bedford. His son Perry, Robert’s great-grandfather, took up the grant, beginning the establishment of Borden families in the Annapolis valley bordering on the Bay of Fundy.

The Bordens were farmers, tilling the rich tidelands rescued from the sea generations earlier by the expelled Acadians. Robert’s father, Andrew, who was born in 1816, owned a substantial farm at Grand Pré. He first married Catherine Sophia Fuller, and they had a son, Thomas Andrew, and a daughter, Sophia Amelia, before her death in 1847. Three years later Andrew married Eunice Jane Laird, the daughter of John Laird, the village schoolmaster and a classical scholar and mathematician of local repute. Robert was born in 1854 and was followed by a brother, John William, a sister, Julia Rebecca, and another brother, Henry Clifford, born in 1870. John William would become a senior civil servant in the Department of Militia and Defence in Ottawa; Julia remained in Grand Pré, unmarried and living with her parents; Henry Clifford, known as Hal and Robert’s favourite among the siblings, graduated from Dalhousie law school in Halifax and practised as a lawyer.

Of all the members of the family it was Eunice, Robert’s mother, who had the strongest influence on his upbringing and development. He later wrote that she was of “a highly-wrought nervous temperament,” “passionate but wholly just and considerate upon reflection,” and totally devoted to the welfare of her four children. Borden admired her “very strong character, remarkable energy, high ambition and unusual ability” – traits that marked his own emerging personality. Borden’s reflections on his father were much more restrained. Andrew did not take to agricultural pursuits and left management of the farm to Eunice and the children. He dabbled and failed in small business ventures and in time found a comfortable sinecure as stationmaster at Grand Pré for the Windsor and Annapolis Railway. Though “a man of good ability and excellent judgment,” Robert wrote, Andrew “lacked energy and had no great aptitude for affairs.”

Robert’s education began in the village’s Presbyterian Sunday school, where he was initiated into the mysteries of the Shorter Catechism, and at home, where he learned reading with his mother from the pages of John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s progress. In due course, lessons with the village schoolmistress were interspersed with visits from his uncles, who introduced him to the poets Horace and Virgil. When he was nine, in 1863, his parents sent him as a day student to the local private academy, Acacia Villa School, presided over by Arthur McNutt Patterson. Patterson’s mission was to “fit boys physically, morally, and intellectually, for the responsibilities of life.” Each morning began with Patterson reading a chapter of Proverbs to his charges, who then moved on to exercises in grammar, mathematics, literature, and natural philosophy. Borden excelled at Greek and Latin. Soon his instructor, James Henry Hamilton, also had him studying Hebrew. The classical poetry and literature stayed with Borden all his life. A volume in Latin or Greek, perhaps one of each, was on his bedside table until the day of his death. In 1869, when Hamilton suddenly left Acacia Villa to join a private school in New Jersey, Robert, at age 14, found himself promoted to “assistant master,” charged with taking Hamilton’s place in classical studies.

The contrast with his chores at home was sharp and telling. He later recalled that he never had mastered “the mysteries of building a load of hay,” and found hoeing vegetables “extremely disagreeable” and sawing cordwood for winter fires “unpleasurable.” Even on the rich bottomlands and upland fields of “the Valley” the rewards of agriculture were hard won. He never forgot that “throughout the year labour was severe and hours long.” As attached as he was to his family, Borden resolved not to spend his life as a farmer in Grand Pré. Teaching at Acacia Villa had more than its share of routine, and his failure to complete his schooling precluded study at university. Still, teaching hinted at a better way of life. Self-education, he discovered, had its own satisfactions. One learned the value of time: “To waste it seems like wasting one’s future.” Discipline, hard work, persistence, patience, and a sense of humour were common enough virtues but essential to shape the ambitions of a young man determined to succeed. Borden taught at the academy for four years and then accepted Hamilton’s invitation to join him at the Glenwood Institute in Matawan, N.J.

It was the first time he had ever been away from home and he was desperately lonely in the fall of 1873. But he was not alone. A ferry ride away in the great metropolis of New York his half-brother, Thomas, a sailor, and his wife lived. Other Nova Scotia friends resided in Brooklyn and he and a fellow boarder named Horner, a public-school teacher, often went to the city on weekends to visit its parks, museums, galleries, and libraries and to listen to temperance lectures. At the Glenwood Institute, he was a 19-year-old professor of classics and mathematics. Borden found the work demanding. He kept a short-lived diary and frequently recorded entries like “I worked too hard this afternoon at reports &c. I was somewhat ill this evening about 7 o’clock.” He had nine different classes, most with fewer than a dozen students, and none of them particularly challenging.

In the spring of 1874, as the school year was drawing to a close, Borden surveyed his prospects. They were not encouraging; without completion of his formal education in school and college, a career in teaching would likely mean working in second-rate academies trying to inspire dull, uninterested students. Casting about, he wrote to an uncle who was a barrister in Ontario, asking for information on studying law in that province. The reply was enough to convince him that he should give the profession a try. But his mother would have nothing to do with his going to Ontario. She told him he could do just as well at home in Nova Scotia. He applied to and was accepted by the prominent Halifax firm of Robert Linton Weatherbe* and Wallace Nesbit Graham*. As the fall of 1874 began, Borden, always punctilious, recorded: “Commenced the study of the law by reading a small portion of [Robert Malcolm Napier] Kerr’s 1873 edition of the Student’s Blackstone on Saturday evening, Sept. 19 at 8.45 o’clock.”

He was apprenticed to Weatherbe and Graham as an articled clerk for four years, “entitled to be instructed in the knowledge and practice of the Law.” In truth, he learned by doing. He was expected to prepare briefs for his masters and watch over the ordinary office affairs of their clients. Formal instruction depended upon his after-hours initiative. A diversion from the routine of the office was enlisting in the 63rd (Halifax Volunteer) Battalion of Rifles. There, in three yearly terms, he earned a meagre but welcome six dollars for twelve days of service and a fifty dollar bonus when he qualified for commission. Other companions were found at the St Andrew’s Lodge of British Templars and the debating society of the Young Men’s Christian Association. In September 1877 he joined Charles Hibbert Tupper*, who had a law degree from Harvard, and 23 others to sit the provincial bar examinations. Borden topped the class. He still had a year of apprenticeship before admittance to the bar and during the winter of 1877-78 also attended the School of Military Instruction in Halifax.

Borden and a classmate briefly had a practice in Halifax before he went to Kentville as the junior partner of Conservative lawyer John Pryor Chipman. Then, in 1882, Wallace Graham called him back to Halifax. John Sparrow David Thompson*, a partner in the firm since Weatherbe’s promotion to the bench in 1878, had himself been made a judge. Graham and Tupper, who had become a partner in 1881, needed help, especially so because Tupper had just been elected to the House of Commons. Borden had hardly settled in when Graham assigned him a long list of cases before the provincial Supreme Court. Other work came from the firm’s Conservative friends in Sir John A. Macdonald*’s government in Ottawa. Borden helped prepare the government’s cases in the seizure of two American fishing vessels in 1886 during the long-standing Canadian-American dispute over fishing rights in the North Atlantic. Then, early in 1888, Thompson, now Macdonald’s minister of justice, invited Borden to work with him in Ottawa as deputy minister. Borden was tempted but declined, preferring to remain in practice in Halifax.

In September 1889 Robert Borden married Laura Bond, a daughter of the late Thomas Henry Bond, who had been a successful hardware merchant in Halifax. How they first met is not known, though it may have been at St Paul’s Anglican Church, where she was an organist and he a regular attendant. Their courtship had begun in the summer of 1886. When they were married he was 35 and she 28. Laura was a lively, attractive, and strong-willed young woman whose interest in music and theatre complemented his in literature. Both enjoyed tennis, water sports, and especially golf. At first the Bordens rented rooms in downtown Halifax but in 1894 Borden bought a large home, Pinehurst, on Quinpool Road in the western suburbs of the city. He was now very successful in his career, and he and Laura spent several weeks in the summers of 1891 and 1893 touring in England and Europe. There were no children of the marriage but Borden’s brother Hal was often with them at Pinehurst while studying at Dalhousie.

By the mid 1890s the Borden firm, now including William Bruce Almon Ritchie* and others, was among the largest in the province. The Bank of Nova Scotia, Canada Atlantic Steamship, Nova Scotia Telephone, and the bread and confectionery business of William Church Moir* were among its prominent clients. Most of Borden’s work was on referral of appeals to the Supreme Court in Halifax or in Ottawa, and in 1893 he appeared for the first time before the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London. He had several cases each year in Ottawa. While there he frequently visited Sir John Thompson, who had become prime minister, and other Nova Scotia acquaintances. His closest friends were the Tuppers, Charles Hibbert and his family. In the early nineties Borden and Tupper took up the new fad of bicycling and were often seen on the roads in and about Ottawa and Hull. At home in Halifax, Borden’s reputation and influence in the bar steadily grew. He was elected vice-president of the Nova Scotia Barristers’ Society in 1895 and became its president a year later. While he was serving in that office he and his colleague Charles Sidney Harrington played leading roles in organizing the founding meeting of the Canadian Bar Association in Montreal in 1896.

That spring, on 27 April, Borden was in Ottawa arguing cases and went to dinner at Sir Charles Tupper*’s home. It was the day that Sir Mackenzie Bowell* resigned as Conservative prime minister and Tupper was about to succeed him. It was clear that there would be an election before the year was out. Tupper asked Borden to stand for Halifax with the veteran Catholic mp Thomas Edward Kenny*. John Fitzwilliam Stairs*, Halifax businessman and Protestant colleague of Kenny in the House of Commons, was stepping down and Tupper wanted Borden to replace him. Before Borden left the dinner party, he accepted.

It was an abrupt change in Borden’s life and opponents would later charge that he had suddenly switched sides. What political interests he had had in his earlier years were certainly on the Liberal side – the Valley was a Liberal stronghold – and he had spoken once on behalf of his cousin the Liberal politician Frederick William Borden* in 1882. In 1886, however, he had abandoned the Liberal cause in disagreement with Nova Scotia premier William Stevens Fielding*’s campaign against confederation. Several of his legal partners in Graham’s firm were prominent Conservatives and when Borden took over the firm all the new associates he chose had Conservative leanings. Yet Borden himself had never before expressed any interest in running for public office. Nor was he deeply moved by the big issue in the 1896 election, the Manitoba school question [see Thomas Greenway*]. After winning the nomination he campaigned on the hardy staple of Macdonald-era Tory politics, the National Policy. This, after all, was the plank in the Conservative platform that captured the interest and support of most of his clients. On election day, 23 June, Halifax voters, for only the second time since confederation, split their ticket. Both the Conservative and the Liberal Catholic candidates were defeated. Borden and Liberal Benjamin Russell, another prominent lawyer and Protestant, were elected. Borden took his place in the commons as a member of the opposition party: Tupper and his Tory colleagues had been soundly defeated by Wilfrid Laurier*’s Liberals.

For the next four years Borden was a backbencher, practising law in Halifax and politics in Ottawa. He disliked being away from Laura. “It is a miserable irregular life one has to lead,” he complained early in the 1896 session, “and I am more than sick of it, I can assure you.” As always, the duties of the backbencher revolved around attending to the wishes and complaints of his constituents and defending the interests of his riding when occasion demanded. Borden became involved in his work on house committees and, over time, grew more confident to speak on broader, national issues. As one of the few “new men” in the party, he was steadfast in his loyalty to his leader, Tupper, and distanced himself from the incessant bickering that characterized the Conservatives in opposition. By 1899 he had been moved to the front bench and had begun to be noticed as an emerging figure in the party.

On 7 Nov. 1900 the Conservatives were soundly defeated in another general election and Tupper was ready to give up the leadership at year’s end. The more obvious candidates were veteran warriors such as George Eulas Foster and Sir Charles Hibbert Tupper. But they had acquired as many rivals and enemies as friends during their long careers, and their prospects of beating Laurier in a future election were dismal. The party needed a fresh face and the Tuppers, father and son, turned to Borden. He had no enemies in the caucus and had been an able and conscientious worker in parliament. Charles Hibbert approached him in mid November, well before his father’s formal resignation was announced in February. “I have not either the experience or the qualifications which would enable me to successfully lead the party,” Borden replied. “It would be an absurdity for the party and madness for me.” The Tuppers persisted and when the disheartened Tory mps and senators met in February 1901, they rallied support for their candidate. On 6 February the members, many sceptically, chose Borden as their leader. Borden played out the formalities of surprise and set two conditions. He would, he said, accept for only one year and he demanded that the party appoint a committee to search for a permanent leader. The committee was quickly forgotten and the commitment to one year was never made public.

Borden led the party in opposition for a decade. Previous leaders, Macdonald, Thompson, Tupper, and the others, had had years of parliamentary experience before assuming the position. Borden, in his late forties, had spent his adult life as a lawyer and had had only a brief apprenticeship in politics. Though he applied himself to his new duties with the same earnestness and ambition that he had devoted to his legal career, he regarded politics with a sense of detachment unknown to the career politicians who preceded him. Political life, he believed, was a responsibility, something a successful man should take on in the public interest. While he had long since conquered his anxieties about arguing the law in the highest courts of his country and the empire, Borden never enjoyed public speaking and debate. He found it both physically and emotionally demanding.

Leading his colleagues was even more challenging. They were a fractious lot in parliament and the constituencies, cursed with long-standing rivalries and deep divisions between Catholic and Protestant, French and English, and, reflecting changing times, urban and rural factions. Though ultimately the leader had the authority to decide, party organization and party policy had evolved as prerogatives of the mps, which they jealously guarded. They chafed at Borden’s tendency, throughout the opposition years, to bypass them and seek advice from outsiders, Conservative provincial premiers and prominent business leaders sympathetic to the Tory cause. One veteran of party warfare, Samuel Hughes*, developed a strong affection for his leader but shared his long-serving colleagues’ doubts about Borden’s political skills. Borden, he observed in 1911, was “a most lovely fellow; very capable, but not a very good judge of men or tactics; and is gentle hearted as a girl.” Many mps found Borden reserved, distant, and occasionally imperious. Once, in 1913, Borden had to reprimand a colleague and then regretted it. “Wrote [John Allister Currie] a consoling letter,” he wrote in his diary. “He wept. Geo[rges] Lafontaine also wept today when I spoke kindly to him.”

Borden’s most difficult problem was with his French Canadian mps. Once the backbone of the Conservative Party, the Quebec membership in caucus had been reduced to a tiny rump. Borden often thought their ideas were parochial but never went out of his way to try to understand them. Following a practice of Macdonald, he chose a lieutenant from their ranks, Frederick Debartzch Monk*. Monk, like Borden, was a lawyer who had first been elected in 1896 and, again like his chief, he was serious, earnest, and moody. Neither man got on easily with the other. Monk was a champion of growing nationalist sentiment in Quebec. Borden, who spoke competent French, was frequently impatient with his lieutenant and failed to grasp the significance of French Canadians’ views on national issues that threatened their sense of identity. Nor was he able to curb the sometimes virulent antagonism of his more ardent Ontario Protestant colleagues to the Quebec Conservatives’ aspirations. Monk, feeling isolated and unsupported by his leader, resigned his position in January 1904. A year later he and Borden clashed over the schools issue in Alberta and Saskatchewan. Monk wanted Borden to stand up for establishing separate schools in the new provinces while Borden, knowing they were opposed by local officials, backed the arguments for provincial autonomy. Monk, angered, said that his leader had set back the Conservative cause in Quebec by 15 years.

Borden was influenced by the progressive ideas about democratizing political parties and using state power in the public interest that were being debated in the United States. An example was his opposition to the extravagant plans of Laurier’s government, in 1903, to support the building of two more transcontinental railways, the Grand Trunk Pacific and the Canadian Northern. Borden agreed that the rapid expansion of the prairie region required new transportation routes. But the two railways, which would run for miles within a carriage ride’s distance of each other, were wasteful and irresponsible. He countered with a proposal for a government-owned and -operated transcontinental railway, controlled not by private corporations but by the people of Canada. Though the Liberals easily carried the day in parliament, Borden said that in the forthcoming general election the people would have a choice, “a government-owned railway or a railway-owned government.”

It did not work. Laurier’s Liberals, at the peak of their power, humiliated the Tories in the election of November 1904. They took every seat in Nova Scotia, including Borden’s, swept British Columbia, and increased their majority to 64. Borden talked of resigning. But the attractions of public life had begun to grow on him: he enjoyed the recognition a party leader received and the continual association with men of affairs that political life demanded. His confidence in his performance as leader had grown and his job was unfinished. “For a long time I more than hesitated” about staying on, he would tell his friend John Stephen Willison*. But just before Christmas 1904 he decided to remain as party leader. “I have put all the hesitation and doubt behind me and I shall endeavour to do my full duty.” A vacancy was hastily found in Carleton constituency in Ontario and Laurier graciously arranged that Borden be acclaimed on 4 Feb. 1905.

Shortly after his election it was clear that Borden’s commitment to national politics was complete: he told Laura on 9 February that he was house hunting in Ottawa. The couple moved into their new home, Glensmere, on Wurtemburg Street and backing onto the Rideau River, in the summer of 1906. Borden spent much of his second term as leader developing a new platform for his party. A scheme to hold a policy convention was mooted and then shelved when Quebec Conservatives declined to attend. He turned for advice to the Conservative provincial premiers, Richard McBride* in British Columbia, Rodmond Palen Roblin in Manitoba, and James Pliny Whitney* in Ontario, to some of the new members of his caucus who shared his views, and to businessmen such as Joseph Wesley Flavelle and Sir Thomas George Shaughnessy*. He announced his Halifax Platform – in his words, “the most advanced and progressive policy ever put forward in Federal affairs” – in his home city on 20 Aug. 1907. It called, among other things, for reform of the Senate and the civil service, a more selective immigration policy, free rural mail delivery, and government regulation of telegraphs, telephones, and railways and eventually national ownership of telegraphs and telephones. The proposals received a cool reception from his parliamentary colleagues who had not been consulted and a mixed public reception among businessmen who were concerned by Borden’s unorthodox ideas about state intervention in business affairs. Though he spent more than a year promoting the platform in speeches across the nation, the effort was not enough to prevent another victory by the Liberals in October 1908.

Borden had now lost two general elections and his party four in a row. But in 1908 the Conservatives gained 14 seats, reducing Laurier’s majority to 50. Borden was more determined than ever to carry on. Many of his parliamentary colleagues had other ideas. They resented having been ignored in the planning of the Halifax Platform. They feared his ideas for developing party structures that would lessen their influence. And he had now led them to another painful defeat. They carried their discontent into the new parliament, a parliament soon dominated by two issues that challenged Canadians’ views of their relationship with the United Kingdom and the United States and that triggered successive revolts against Borden’s leadership within his caucus. The struggle appeared to be over Borden’s determination to break the mps’ dominance of party affairs by holding a national convention and establishing a counterweight of democratically controlled local organizations. But what sparked the revolts was Borden’s stand on the naval question in 1909-10 and on reciprocity with the United States in 1911.

In February 1909 the Conservatives placed upon the order paper of the House of Commons notice of a resolution recommending that Canada provide for its own coastal defence, something Laurier had promised in 1902 but never acted upon. Early in March, before the resolution could be debated, a short-lived crisis in Great Britain over the relative strengths of the imperial and German navies shocked and surprised both parties. In English-speaking Canada public figures and many of the large urban dailies demanded a Canadian contribution to the sudden apparent shortfall in British Dreadnoughts. Neither Laurier nor Borden was sympathetic to this clamour. Laurier proposed an amendment to the Conservative resolution, recommending that the house approve any necessary expenditure designed to promote the organization of a Canadian naval service which would work in close cooperation with the imperial navy. It was quickly accepted by the Conservatives and the revised resolution passed unanimously at the end of March. By then, however, the demand for a contribution of Dreadnoughts had been embraced by Borden’s three strongest allies, premiers McBride, Roblin, and Whitney.

In January 1910 Laurier introduced a bill to create a Canadian naval service, with ships stationed on both the Atlantic and the Pacific coasts. If required, they could be put at the service of the imperial navy in time of war. The Conservatives were deeply divided. Monk, whom Borden had reappointed as his Quebec lieutenant a year earlier, was demanding a plebiscite on the issue. Borden continued to support the concept of a Canadian naval service – though not necessarily the one proposed by the Liberals – but now also favoured immediate aid. Many other Tory members wanted a simple, outright contribution to the imperial navy. Before the session was over Laurier’s proposal would be carried by his party’s large majority and soon become law. In early April the Toronto Daily Star broke the story of seething discontent in the Tory caucus, claiming as many as seven different factions at war with each other. That was not true but there were three groups, the French Canadians and two small cliques of English Canadians, who were challenging Borden’s authority and calling for McBride to abandon Victoria and rescue the national party in Ottawa. Borden responded by handing his resignation as party leader to the chief whip on 6 April. He had no intention of leaving. Instead, he was challenging his caucus. He addressed it for an hour on the 12th and left knowing that his allies would beat back the revolt. Shortly after noon a motion reaffirming support for him was passed by all.

In November 1910, responding to an invitation from the United States, Laurier sent his ministers of finance and customs to Washington to discuss a new Canadian-American trade arrangement. After another session there in January, the finance minister, William Fielding, announced the agreement in the house on the 26th. It was staggering in its breadth. The two nations undertook to eliminate customs duties on a long list of natural products. Then there was another long list of reduced duties on many manufactured goods. The arrangement concluded with two further lists, one Canadian and one American, of lower duties on yet more processed products of the other nation. To avoid the possibility of the agreement being defeated in the United States Senate if it was styled a treaty, it had been decided to bring it into effect by reciprocal legislation. The Conservatives, to a man, were stunned. There had never been such a challenge to their National Policy; there had never been a proposal so calculated to win the support of the vast majority of Canada’s farmers, fishermen, lumbermen, and industrial workers. Laurier’s party, though old, tired, and slipping badly in its organizational prowess, seemed assured of another sweeping victory; Borden’s men faced a fifth deeply humiliating defeat.

It was the Tory premiers who initially rallied the troops. For them the issue was not a cheaper cost of living for ordinary Canadians, it was a betrayal by Laurier of Canada’s cherished ties to the empire. Robert Rogers, Roblin’s minister of public works in Winnipeg, told Borden the reciprocity agreement was a “departure from Imperialism to continentalism.” Then the manufacturers, who had prospered under the protection of National Policy tariffs sustained by both Conservative and Liberal governments since 1879, took up the cause [see Sir Byron Edmund Walker*]. The Canadian Manufacturers’ Association quickly developed a shadowy subordinate, the Canadian Home Market Association, to carry on a propaganda war against reciprocity. Soon important business spokesmen who had long supported Laurier’s party, Zebulon Aiton Lash* and Lloyd Harris, joined Clifford Sifton*, a former minister in the Liberal cabinet, and John Willison, the Conservative editor of the Toronto News, to propose an alliance with Borden’s party. Their delegation met him on 1 March, anticipating that the reciprocity issue would force a new election. What would Borden do if he won? They asked that he consult their spokesmen before appointing his cabinet and that its membership include “men of outstanding national reputation and influence” who would appeal to the “progressive elements” of the electorate. In short, they wanted representation of the anti-reciprocity Liberals in his cabinet. Borden quickly agreed and a curious coalition against the trade agreement began to emerge under his leadership.

A large majority of his caucus, led by its more recent members from the business class such as Herbert Brown Ames*, George Halsey Perley, and Albert Edward Kemp*, supported Borden’s developing strategy. But a group of veteran Tories, including Monk and his friends, were appalled by Borden’s pact with Sifton and the anti-reciprocity Liberals and denounced it in a stormy March caucus. Borden again threatened to resign, triggering a petition asking him to carry on. Sixty-five members signed; twenty did not. For a second time in a year opposition in his caucus had been crushed just as the prospects for eventual electoral victory looked better than they had in 15 years. In the House of Commons the party obstructed progress on the reciprocity bill. After a two-month adjournment to allow Laurier to attend an imperial conference, the Liberals lost control of the commons, abandoned their bill, and dissolved the house on 29 July. Borden and his coalition allies campaigned across English-speaking Canada on the slogan “Canadianism or Continentalism.” Their appearances in Quebec, Laurier’s fortress, were few. In a tacit understanding the fight there was left to Monk, his Nationaliste friend Henri Bourassa* (a roommate of Borden years before), and Monk’s parliamentary colleagues. For them the issue was not reciprocity, it was Laurier: Laurier and his Naval Service Act, Laurier and his capitulations to English Canadian interests through the years, Laurier and his alleged corrupt dominance of politics in Quebec.

The strategy worked brilliantly. On 21 Sept. 1911 the Conservatives took all seven seats in British Columbia, eight of ten in Manitoba, and seventy-three of eighty-six in Ontario. In Quebec their representation jumped from eleven to twenty-seven. Borden’s Tories had won 134 seats in the House of Commons; Laurier’s Liberals were returned in 87 constituencies. Borden was the new prime minister of Canada.

Borden’s cabinet mirrored the groups that had won the election under the Conservative banner. All the Conservative premiers, McBride, Roblin, Whitney, and John Douglas Hazen of New Brunswick, were offered places but only Hazen accepted, becoming minister of marine and fisheries and minister of the naval service. The other three chose to have their interests protected by surrogates. Martin Burrell, an mp and a friend of McBride, became minister of agriculture; Robert Rogers from Manitoba accepted the Department of the Interior; and Francis Cochrane* from Ontario took Railways and Canals. William Thomas White*, a talented young financier and vice-president of the National Trust Company, was the nominee of the anti-reciprocity Liberal interests. Though he had no political experience, he was appointed minister of finance and quickly became a close friend and trusted colleague of Borden. There was no shortage of veteran Tories waiting to be called. George Foster, deeply hurt that he did not get Finance, took Trade and Commerce. Sam Hughes unblushingly wrote to Borden celebrating his credentials – “I get the name of bringing success and good luck to a cause” – and was rewarded with the patronage-rich Department of Militia and Defence. John Dowsley (Doc) Reid*, who had been a leader in the caucus revolts against Borden, was named minister of customs. From Quebec, Monk represented the Nationaliste forces as minister of public works and Louis-Philippe Pelletier* and Wilfrid-Bruno Nantel were selected from the more traditional Bleu wing of Conservative support. English Quebec was recognized by Charles Joseph Doherty’s appointment as minister of justice.

The new government began with high hopes for a mildly progressive legislative program. From the Halifax Platform, Borden promised further reform of the civil service – Laurier had begun the process with the establishment of the Civil Service Commission in 1908 – but sidestepped the more controversial ideas of government regulation or public ownership of national franchises such as the telegraph and telephone systems. The farmers, who were the principal victims of the defeat of reciprocity, needed attention. The Canada Grain Act of 1912 established a board of grain commissioners to supervise grain inspection and regulate the grain trade, and enabled the federal government to build or acquire and operate terminal elevators at key points in the grain marketing and export system. By 1916 the government would have elevators in operation at Port Arthur (Thunder Bay), Ont., Moose Jaw, Sask., Calgary, Saskatoon, and Vancouver. A second measure provided financial support to the provinces for the purpose of encouraging agriculture. Another proposal had the backing of many manufacturers and businessmen. The government introduced a bill in 1912 to establish a tariff commission, an innovation that had been mooted in the Halifax Platform; it was to apply “scientific principles” to management of the tariff, which accounted for more than 80 percent of the government’s revenue, and remove it from partisan influences. Yet another measure that year called for financial assistance to the provinces to build or improve provincial highways and begin the construction of a national highway system. All of these initiatives seemed promising and a distinct departure from the Laurier era.

Then, in March 1912, two different issues threatened the administration’s cohesion and policies: education and the navy. To fulfill an election promise, the Manitoba boundary was extended to annex part of the District of Keewatin. Despite protests from French Canadian colleagues, Borden held that Ottawa could not force Manitoba to provide guarantees for separate schools that did not exist at the time of the transfer. Rogers smoothed things over by arranging a compromise whereby Roblin’s government agreed to deal justly and tolerantly with Manitoba Catholics on the schools question, but resentment was only banked, not extinguished. On the 18th of that month Borden announced that the Liberals’ naval program was, in effect, halted, and he would be preparing a permanent program of his own, although he added that “we are maintaining the [naval] organization so far as may be necessary and desirable until a definite policy can be arrived at.” He had made a major tactical error, enraging the opposition and leaving Canada’s naval service in limbo. The Liberals, who had a huge majority in the Senate, retaliated. Borden’s tariff commission was rejected in 1912 and his highways bill in 1912 and again in 1913.

The same day that Borden declared his intentions concerning the naval plan Winston Churchill, Britain’s first lord of the Admiralty, announced a new construction program for the Royal Navy to counter a growing threat from Germany. Once again the contribution-minded Tories in English-speaking Canada demanded action, and Borden, Hazen, Doherty, and Pelletier soon left for consultations in London; Monk refused to go. In the fall of 1912 Borden told his colleagues that his permanent naval plan was postponed and he was going to make a contribution of Dreadnoughts. The debate among them dragged on for some weeks, with Monk again insisting that there must first be a plebiscite. On 18 October, realizing his position was hopeless, he resigned from cabinet. On 5 December Borden introduced his Naval Aid Bill, which was to provide $35 million for the construction of three Dreadnoughts to be placed “at the disposal of His Majesty the King for the common defence of the Empire.” Borden expected something significant in return. He was convinced that support for the imperial cause had to be recognized by Canada having a voice in the determination of imperial foreign policy. Following his conversations in London he believed he had received that concession and announced to the house that “no important step in foreign policy would be undertaken without consultation with . . . a representative of Canada.”

The debate in the house also went on for weeks, becoming ever more acrimonious. After an all-night session in March, Borden recorded, “Our men angry at end and both sides wanted a physical conflict. Primeval passions.” Then, on 9 April, for the first time in the Canadian parliament, the government introduced closure and a month later the bill passed. But the “gagged” opponents had their revenge. The Senate rejected the Naval Aid Bill at the end of May [see Sir James Alexander Lougheed*]. Canada’s naval service was in suspension, its emergency contribution to the Royal Navy dead. The impasse would continue in June 1914, when the Senate rejected a bill, unanimously passed in the commons, to increase its numbers so as to give adequate representation to the western provinces. With partisan bitterness at a peak and good portions of its legislative program crippled, the Tories called out the battalions for a snap general election. Borden had one plank to put to the people: a pledge to amend the constitution and have an elected Senate. However, the weakness of the party in Quebec and in Manitoba, where Roblin won only the barest of majorities in July, combined with the illness of Whitney in Ontario, caused him to draw back.

On 22 June 1914 the king had awarded Borden the gcmg. Late in July, he and Laura escaped Ottawa’s summer heat for a vacation in Muskoka. It was short-lived. On Friday morning, 31 July, Borden was on a train rushing for Toronto. The next day he was in his Ottawa office and on Tuesday evening, 4 Aug. 1914, at 8:55 a cable from London arrived during an emergency cabinet meeting. Canada was at war.

The war was greeted with enthusiasm. Prominent men of affairs competed for recognition of their contributions to the war effort. Robert Rogers guaranteed to support the dependants of members of the Fort Garry Horse who joined up. Clifford Sifton donated a battery of armoured cars, and Andrew Hamilton Gault* raised a battalion of ex-soldiers, the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, that were the first Canadian troops to land in France. The Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire solicited funds for a hospital ship. And Sir Richard McBride surprised both the Admiralty and Ottawa when he used provincial funds to purchase two submarines being built for the Chilean navy in Seattle and had his operatives slip them over the border just as the United States neutrality laws were coming into effect.

In Ottawa, the government was unprepared for war. So was the nation. The only member of cabinet with any military experience, and it was chequered, was Sam Hughes. Key departments of the public service – Finance, Justice, Trade and Commerce, and Labour – each had fewer than one hundred employees as late as March 1915. Small arms (the Ross rifle) were manufactured in Canada but there was no capacity, or manpower, to produce heavy armaments. A much-touted war book, quickly implemented, barely hinted at what a government at war needed to do. But by Sunday, 9 August, the basic orders in council had been proclaimed, and a war session of parliament opened just two weeks after the conflict began. Legislation was quickly passed to secure the nation’s financial institutions and raise tariff duties on some high-demand consumer items. The War Measures Bill, giving the government extraordinary powers of coercion over Canadians, was rushed through three readings. Finally, the Canadian Patriotic Fund was set up to assume responsibility for assistance to the families of soldiers. With complete support from Laurier and his party, the government’s war legislation was in place in just five days.

The centrepiece of the effort was recruiting the force that Canada would send to the front. Hughes abandoned a mobilization plan that had been drawn up by the chief of the general staff, Colonel Willoughby Garnons Gwatkin*, and turned recruiting over to the more than 200 local militia commanders. Chaos reigned while Hughes went on to contract businessman William Price* to build a training site from scratch at Valcartier, near Quebec City. In less than three weeks the camp had been established and thousands of troops had arrived. A division had been offered as Canada’s contribution; many more men were at Valcartier and, while Hughes strutted and dithered, Borden decided late in September to send them all to England. The men were not trained and would spend months on Salisbury Plain in winter learning the rudiments of warfare [see Sir Edwin Alfred Hervey Alderson*]. The fear in the government, and the country, was that the Canadians would not get to the front in time: it was widely anticipated that the war would be over by Christmas. On 18 Dec. 1914 Borden told the Halifax Canadian Club that “there has not been, there will not be, compulsion or conscription.”

The eagerly awaited “decisive battle” that would crush the Germans never happened. Almost immediately the Western Front settled into years of ghastly skirmishes and inconclusive trench warfare. In April 1915, when the 1st Division fought its first major battle, at second Ypres, Canadians became acquainted with the growing casualty lists that appeared in urban dailies and rural weeklies from Nova Scotia to British Columbia. Recruiting for a second division had begun as the first was crossing the Atlantic. The authorized force level of the Canadian army rose again and again: 150,000 in July 1915; 250,000 in October 1915; and finally 500,000 in January 1916. Throughout, Hughes left the responsibility decentralized in the local units and military districts: his department remained on the sidelines. The recruits, very largely from Canada’s towns and cities, came by the thousands – until mid 1916. By then the war effort in factory and field was running at full capacity and labour shortages were appearing on production lines and farmsteads alike. By then, too, the reality of a war of attrition had been grasped. Potential recruits had a choice not open to many in 1914 and early 1915 when unemployment had reached serious levels: there was a very dangerous job available at $1.10 a day in France and another at unprecedented wages in the home-front war economy. By July 1916 the seemingly endless flow of recruits had become a mere trickle: 8,389 men. In April and May 1917, especially in the aftermath of Vimy Ridge, just over 11,000 men enlisted. The days of volunteerism were over.

The government’s approach to the war effort at home paralleled the volunteerism of military recruiting. Worried that an already troubled economy might collapse because of “uncertain conditions,” Borden and White had opted for “business as usual.” In 1915 White rejected calls for direct taxation. It would cost too much to implement, he said, and would intrude upon a tax field traditionally used by the provinces. After the London market closed at the end of 1914, White, reluctantly and complaining about the high rates charged, turned to New York for bond issues in 1915, 1916, and 1917. He did not believe that the Canadian market was big enough to sell major issues. But a very tentative offering of $50 million in 1915, spurred by the escalating costs of the war, was doubly subscribed. Much larger issues in 1916 and 1917 were equally successful and a Victory Loan of $300 million in 1918 brought in $660 million. In the manufacturing sector Sam Hughes’s hastily appointed Shell Committee vied for munitions orders from the Allied governments. The Canadian government’s contracts for the many needs of its soldiers were dispersed by Militia and Defence and other departments in the partisan ways that had been practised for decades. Then minor scandals in early 1915 persuaded Borden to set up the War Purchasing Commission under Edward Kemp, now minister without portfolio. It took over the contracting for Canada’s military expenditures and for all British and Allied orders for war supplies except munitions. Scandals also struck the Shell Committee, and in November 1915 it was shut down and replaced, as contractor for munitions, by the Imperial Munitions Board under the leadership of Joseph Flavelle.

These were the first manifestations of change. Others followed as war production in the factories and on the farms of Canada began to grow. In response to an urgent need for foodstuffs in Europe, Borden’s government commandeered the 1915 wheat crop. In 1917 skyrocketing prices led to the establishment of the Board of Grain Supervisors of Canada under Robert Magill*, which took marketing of the crops of 1917 and 1918 away from the private grain companies. It was succeeded by the Canadian Wheat Board with the same mandate for the 1919 crop. Also in 1917, a food controller, William John Hanna*, was appointed to regulate the production and distribution of Canada’s food supplies and a fuel controller, Charles Alexander Magrath*, was given the power to regulate the distribution and price of fuels and the wages of coalminers in Alberta and Nova Scotia. A year earlier, responding to increasing concern about war profiteering by Canada’s businesses, Borden and White had reversed themselves on the tax issue and imposed the nation’s first direct impost, the business profits war tax. It was politically motivated. So too was the income war tax, grudgingly introduced by White in 1917 as a companion to the Military Service Act, ostensibly to conscript the excesses of the nation’s wealth to match the forced enlistment for military service. The rates were deliberately low and affected only a minority of people, and the impact of the two direct taxes on the government’s revenue was insignificant. Both, as well, were temporary, intended to end with the end of the war. The profits tax expired in 1920 but was revived in World War II and the income tax would become the federal government’s largest permanent source of revenue. In 1916 the deep and long-lasting problems of the new transcontinental railways were temporarily alleviated through government loans; the crisis was finally resolved the following year with the takeover of the Canadian Northern Railway [see Sir William Mackenzie*; Sir Donald Mann] and the initial steps toward nationalization of the Grand Trunk-Grand Trunk Pacific system [see Edson Joseph Chamberlin*]. The Canadian National Railways, government-owned and operated by an arm’s-length board, would incorporate both lines with other government railways. In short, by 1917 precedent and tradition had been abandoned; business as usual had given way to remarkable government intervention in the economy.

Dramatic and unanticipated changes also took place in policy towards military manpower and in imperial relations. Borden made his first wartime visit to Britain and France in 1915. In Paris he visited President Raymond Poincaré and received the grand cross of the Legion of Honour. In London the government of Herbert Henry Asquith was welcoming and cordial but refused to concede any possibility of consultation on war policy. That was true also in 1916 as Borden wrestled with the chaotic administration of military manpower in Canada and Britain under Hughes. Eventually, in the fall of 1916, Hughes, in London, deliberately defied Borden’s instructions for management of the overseas forces. Borden stripped him of his responsibilities and, in response to Hughes’s bitter reaction, fired him in November. Hughes was replaced in Ottawa by Edward Kemp, and in London a new ministry of overseas military forces was established with George Perley, Canada’s acting high commissioner, as its minister.

In December the new British prime minister, David Lloyd George, initiated a revolutionary change in the United Kingdom’s relations with its dominions. He desperately needed more fighting men but realized that the time had come to give the dominions and India some say in the direction of the war. “They are fighting not for us,” he was reported as saying, “but with us.” In the spring of 1917 Borden, the leader of the senior dominion, attended the first imperial war cabinet and conference. Between regular visits to Canada’s soldiers in military hospitals, Borden participated in war-cabinet discussions of a wide range of matters, including possible peace terms. At meetings of the conference he and his brilliant young legal adviser, Loring Cheney Christie*, led the passage of Resolution IX, which called for a post-war constitutional conference to “provide effective arrangements for continuous consultation in all important matters of common Imperial concern, and for such necessary concerted action, founded on consultation, as the several Governments may determine.”

Back in Canada, Borden met his cabinet on 17 May and told them that he was ready to introduce conscription. The pressure to impose compulsory service had been building for more than a year, especially among more well-to-do English Canadians convinced that Quebeckers were slackers who refused to do their part. In 1916 the Toronto-based Bonne Entente movement, organized by John Milton Godfrey* and Arthur Hawkes, sought but failed to win Quebeckers over to a greater military contribution to the war effort. The more strident Win-the-War movement in 1917 openly agitated for conscription and a coalition government to enforce it. Quebeckers were not impressed. They were angered that Borden’s government had failed to support their demands for redress of the grievance felt by Franco-Ontarians as a result of the Whitney government’s imposition of Regulation 17 on their schools [see Philippe Landry*]. This 1912 regulation had abolished the use of French as a language of instruction beyond form one (the first two years of instruction). In Ottawa the dispute was particularly heated as resistance to the regulation grew year by year, leading the government of William Howard Hearst* to effectively put the Ottawa school board in trusteeship in 1915 [see Samuel McCallum Genest]. In February 1916, nearly five thousand angry French Canadians marched in protest to Borden’s office and demanded federal intervention in the dispute. Borden said he would “see what could be done.” He did nothing, firmly convinced that the dispute was strictly a provincial matter. Then in April his three French Canadian ministers, Pierre-Édouard Blondin*, Thomas Chase-Casgrain*, and Esioff-Léon Patenaude* pleaded to have the dispute referred to the Privy Council in Britain. He refused, calling their request “foolish.” In May Liberal mp Ernest Lapointe*’s resolution in the commons recommending to the Ontario legislature “the wisdom of making it clear that the privilege of the children of French parentage of being taught in their mother tongue be not interfered with” was soundly defeated with “loud cheers” by the Tory majority. Ominously, five of Borden’s members voted for the resolution and eleven of Laurier’s caucus voted with the majority. Borden’s view that intervention was unconstitutional was sound, but his insensitivity to French Canadians’ concerns and to the pleas of his Quebec colleagues, and his adamant refusal to intervene with the Conservative government in Toronto, all but eroded what limited support his government had in Quebec. The increasingly strident clamour for conscription made matters even worse and sharpened the growing division between French and English in Canada.

For months Borden had resisted the conscription agitation, fearing large-scale unrest if it was imposed. “That might mean civil war in Quebec,” as he told one of the Bonne Ententists. In May 1917, when cabinet was informed there would be conscription, Blondin and Patenaude warned that it would “kill them politically and the party [in Quebec] for 25 years.” Borden’s participation in the imperial war cabinet and his keen awareness that voluntary recruiting had fallen well behind battlefield casualties had been decisive in changing his mind. Casualties in the spring of 1917 were double the number of new recruits. Being taken into the imperial government’s council, participating in discussions of war and peace policy at the centre of the empire, Borden believed, heightened Canada’s responsibility to do everything possible to support its soldiers. Even more important was the bond he had established with “his boys” at the front and in the long rows of hospital beds in England. When he introduced the Military Service Bill on 11 June, he asked a hushed and sombre House of Commons, “If we do not pass this measure, if we do not provide reinforcements, if we do not keep our plighted faith, with what countenance shall we meet them on their return?”

At that same cabinet meeting in May, Borden announced that he was going to ask Laurier to join him in a coalition government to support conscription. He did so a week later. Laurier hesitated, opposed to compulsion but aware that several of his English-speaking colleagues strongly supported it. Finally, on 6 June, he refused. Several members of Borden’s cabinet were vastly relieved. They abhorred the idea of cooperating with the Liberals and believed that they could easily win the forthcoming election on a conscription platform without them. But Borden persisted and worked for months to achieve a coalition of his party with conscriptionist Liberals. Along the way his men rammed through two bills to rig the franchise for the coming election. The Military Voters Act made it possible to manipulate the counting of votes at the front, and the War-time Elections Act, which finally passed in late September, disenfranchised enemy aliens who had come to Canada after 1902 and extended the vote to the immediate female relatives of soldiers. This raw display of partisan determination finally tipped the scales for coalition. Dithering conscriptionist Liberals such as Arthur Lewis Watkins Sifton*, Newton Wesley Rowell*, and Frank Broadstreet Carvell* knew that this was their last chance and quickly signed up. The Union government was announced on Saturday, 13 October. There were seven Liberals in the new cabinet, and one more would be added before the end of the month. Doc Reid, who like dozens in the Tory caucus had thought the coalition would never happen, reportedly quipped that he would “back Borden against Job in a patience contest.”

The angry debates that accompanied passage of the Military Service Act, the accusations and recriminations in both parties over coalition, were but preludes to the bitterness of the election campaign that began in November. The Manitoba Free Press (Winnipeg) declared that “a vote for Laurier is a vote for the Kaiser.” Sir John Willison’s paper, now the Toronto Daily News, published a front-page map of Canada: English-speaking Canada was coloured in red, Quebec in black. In Quebec, Albert Sévigny*, Borden’s minister of inland revenue, was driven from a platform amidst revolver shots and flying stones. After he took refuge in a hotel, the building’s windows were smashed and Sévigny had to escape by sneaking out the back door. The campaign of insinuation, intimidation, and violence came to an end on voting day, 17 December. The Unionists won a huge majority of 114 Conservative and 39 Liberal members. Laurier’s Liberals won 82 seats, 62 of them in Quebec and only 2 in western Canada. The disgraceful attempts to fix the vote were a price Borden had been willing to pay. So was the fact that both the great national parties had split – the Grits over conscription, the Tories over the necessity of coalition. For Borden the election of 1917 was a confirmation of “a solemn covenant and a pledge” he, and Canada, had made to the soldiers at the front.

The Union government moved quickly to implement its most important undertakings. Foremost was support for the war effort. The first men called up under the Military Service Act had been required in October to register for service, though in keeping with Borden’s promise not to introduce conscription until an election had been held, they were not to be sent for training until January 1918. The continuing process resulted in hundreds of thousands of petitions across Canada for exemptions and Easter-weekend riots in Quebec City in 1918 [see François-Louis Lessard*]. In due course just under 100,000 single men, aged 20 to 22, would be conscripted. In parliament the War Appropriation Act, for a half-billion dollars, was approved. The enfranchisement of women, partially granted in 1917 as a partisan political ploy, was extended to include all eligible females for the purposes of national elections. A new Civil Service Act quickly passed to start the process of removing the outside service – federal government employees serving beyond the nation’s capital – from appointment by patronage. The Dominion Bureau of Statistics was organized to provide the kinds of systematic information about the nation’s population, social structure, and economy that had been so deficient during the early years of the war. The government also established daylight saving time. The parliamentary session ended in May with a heated debate, initiated by William Folger Nickle*, over the abolition of hereditary titles in Canada. Borden was in agreement: “They are very unpopular and entirely incompatible with our institutions,” he observed. In fact, a March order in council, then under consideration by the British government, had prescribed not only that hereditary titles be abolished but that, except for military distinctions, honours not be conferred on residents of Canada without the approval or the advice of the Canadian prime minister. Later, in mid July, the government belatedly announced a war labour policy which forbade strikes and lockouts for the duration while assuring employees of the right to organize and guaranteeing female workers equal pay for equal work.

In June 1918 Borden and several colleagues had returned to London for the second set of meetings of the imperial war cabinet and conference. He was angry that he had not been consulted before the Canadian Corps had suffered huge losses at Passchendaele and threatened Lloyd George that he would send no more troops to the front if such a situation arose again. More serious still, he had received reports throughout the war critical of the performance of the British high command and of British military planning, reports that reached a peak in his consultations with Lieutenant-General Sir Arthur William Currie, commander of the Canadian Corps. At the second meeting of the war cabinet Borden gave an impassioned speech detailing the faults of the high command. It resulted in the appointment of a prime ministers’ committee which held intensive hearings with officials and senior commanders about the war effort. Its draft report, completed in mid August, gloomily forecast that the war could go on until at least 1920, perhaps longer. It reinforced the commitment to participation by the dominions in war policy and highlighted the need for the civil authorities to exert control over their military commanders. But the report was outdated before it was discussed. Allied forces, spearheaded by Canadian and Australian troops, had attacked at Amiens, launching the final offensive that carried on as Borden returned to Canada.

On 27 October Lloyd George summoned him back to Britain to prepare for possible peace talks. Two days later Borden replied that “the press and the people of this country take it for granted that Canada will be represented at the Peace Conference.” Lloyd George was sympathetic but predicted “difficult problems.” When Borden arrived in London, he proposed that Borden, as the leader of the senior dominion, represent all the dominions at any conference that took place. Borden refused. In December it was agreed that dominion and Indian representatives would be present when questions directly relating to their interests were at stake and that one of the five members of the British delegation at the peace talks would always be from the dominions or India. A month later, after the conference had assembled at Paris, Lloyd George persuaded American president Woodrow Wilson and French premier Georges Clemenceau that Canada, Australia, South Africa, and India would have two delegates and New Zealand one at its plenary meetings. Borden recognized that these were more matters of form than substance and that representation was “largely a question of sentiment.” But, he told Laura, “Canada got nothing out of the war except recognition.” It was a point worth pressing to its logical conclusion: formal acknowledgement of Canada’s international status. On 6 May 1919, as discussions on the membership of the League of Nations were drawing to a close, a memorandum by Borden argued that Canada, as a member, should have the right to be elected to the League’s council. Lloyd George, Wilson, and Clemenceau agreed and added that Canada should also be eligible for election to the governing body of the International Labour Organization. Five days later he was on his way home. It was Charles J. Doherty and Arthur L. Sifton who signed the Treaty of Versailles on Canada’s behalf.

His colleagues in Ottawa were in trouble. The Liberal and Conservative Unionists were squabbling over White’s 1919 budget and arguing over how to deal with the Winnipeg General Strike [see Mike Sokolowiski*]. The strikers were put down with force on “Bloody Saturday,” 21 June. When White’s budget had come to a vote two days earlier, 12 Liberal Unionists joined the opposition. Then White, exhausted by the incessant demands of the war, resigned on 1 August. The next day Liberal Unionist Frank Carvell left. His fellow Liberal Thomas Alexander Crerar* had quit in June over the budget. Conservatives Doherty, Foster, and Burrell also talked of leaving. Other members of the coalition hoped to transform the Union government into a new political party and looked to Borden to lead them. But the prime minister had also had enough. Since 1914 he had responded to the challenges of leadership with an energy and zest that contrasted with his more detached approach to governing in the pre-war years. His soldiers, his country, and the Allied cause had been worth every ounce of effort he could summon. After seeing his government through ratification of the Treaty of Versailles in a short fall session of parliament, and after making provision for the appointment of a Canadian to deal with Canadian affairs at the British embassy in Washington, he was done. “At the end,” he recorded, “I was very tired.”

His doctors advised that he should leave politics immediately. On 16 Dec. 1919 he told his cabinet he was going to resign. Led by Newton Rowell, they pleaded with him the next day to stay in office but take a vacation for a year. Unwisely, he agreed. It did not work. Even on vacation in the south, he was, after all, the leader of the government and could not dismiss the responsibilities of his office. Nor could his colleagues leave him alone. He returned to Ottawa in May and finally announced his retirement to his caucus on Dominion Day, 1920. Caucus then asked him to choose his own successor. It was an unusual request. Both national parties had procedures for changes in leadership. The Tories were long accustomed to selecting a leader in their caucus. In the Liberal Party Laurier’s death in February 1919 had led to the calling of a national convention, which elected William Lyon Mackenzie King* as leader. But the Union government was of neither party and of both. It had no procedure and was as dependent on Borden in leaving as it had been upon him when he formed it. Borden asked each member to indicate to him their three choices for leader. He then recommended White, who adamantly refused. In due course Arthur Meighen*, deeply troubled that he had not been the first choice, was persuaded by Borden to lead the coalition and assume the prime ministership on 10 July 1920.

Sir Robert Borden lived another 17 years. He and Laura remained at Glensmere, where they entertained friends and he took great pleasure in working in his wildflower garden on the bank of the Rideau. In season the couple regularly played golf. There were frequent dinner parties, evenings of bridge, and, in the twenties, the novelty of radio broadcasts. Laura continued her work with various volunteer associations while Borden read and wrote in his library. Two valuable constitutional studies were published: his 1921 Marfleet lectures at the University of Toronto, Canadian constitutional studies (Toronto, 1922), and his 1927 Rhodes lectures at Oxford, Canada in the Commonwealth: from conflict to cooperation (Oxford, 1929). In 1928 he began his memoirs, a manuscript that was nearly finished when he died; it would be published in a hefty two volumes by his nephew, Henry Borden, shortly after his death. Henry would also edit and publish a series of Borden’s Letters to limbo (Toronto, 1971), his reflections on politics, literature, friends, and a host of other subjects which he had written in the 1930s.

Borden was very well off and the couple’s life in Ottawa was as comfortable as it was quiet and understated. In 1901, when he had become party leader, he had had a substantial income from his law firm. That continued until 1905 and was the foundation for a broad range of premium securities in his portfolio. In 1922 he had assets of $800,000, a large sum for the time, and an average annual income of about $30,000; all his expenses, including considerable support for family members and annual trips to the south in late winter, were about $17,000. His fee for a 1922 arbitration of a dispute between Britain and Peru supplemented his income as did his acceptance of the presidency of the Crown Life Insurance Company and Barclays Bank (Canada) in 1928. In 1932 he became the chairman of Canada’s first mutual fund, the Canadian Investment Fund. “There is nothing that oppresses me,” he reported to Lloyd George. “Books, some business avocation, my wild garden, the birds and the flowers, a little golf, and a great deal of life in the open – these together make up the fullness of my days.”

Sir Robert Laird Borden died in early Thursday morning of 10 June 1937. A thousand Great War veterans in mufti lined the procession route from Glensmere to All Saints’ Church for a funeral on Saturday afternoon. He was buried in Beechwood Cemetery in Ottawa.

It was fitting that the veterans, all members of the 1st Division, played a prominent role in Borden’s funeral. World War I had been his greatest political challenge. In 1896 he had been unprepared when Sir Charles Tupper had asked him to run for parliament. Once he had been elected, Tupper and his son Charles Hibbert had guided and encouraged him as he moved from the back to the front benches of opposition. In 1901 he had been unprepared for party leadership. His career as opposition leader was long and conducted against formidable odds with Sir Wilfrid Laurier at the height of his powers and veteran members of his own caucus frustrating his attempts at party reform and challenging his position. In 1911 he had been unprepared for government leadership, and his first years, as a peacetime prime minister, were marked by controversy with both the Liberal-dominated Senate and his own Nationaliste followers and cabinet colleagues from Quebec. In the middle of 1914 Borden was preparing for an election, not war.

After the initial excitement of August 1914 passed, Borden and his colleagues were worried that Canada’s soldiers would not get to the front in time and hurried them to a winter of training on Salisbury Plain. At home his government proceeded with caution and reserve, attempting, as far as possible, to maintain the stance of business as usual. The War Measures Act gave the administration extraordinary powers but it used them sparingly. It tinkered with tariff rates to raise badly needed revenue; it distributed the largesse of hundreds of contracts for war supplies by the tried and true methods of patronage and favouritism; and Borden tried, and failed, to gain access to imperial war planning. What success the government had was in recruiting; young men continued to volunteer in huge numbers throughout most of 1915.

It was clear by 1916 that the war was not going to end any time soon: Canada’s soldiers, now two divisions, were bogged down with their Allies in the dirty trenches of the Western Front. Their casualty rates were appalling and the first cries for conscription were heard on the home front. Borden resisted, fearing compulsion would divide the war effort there, which was producing the goods of war, from food to wagons to munitions, at an unprecedented pace. But the first steps away from business as usual had begun. The domestic market for war bonds had been tapped and had surpassed all expectations. The government introduced the first measure of direct taxation at the federal level in Canada’s history. It also took the first modest steps toward resolving the long-standing fiscal problems of the new transcontinental railways.

By 1917 the last vestiges of hesitation in Borden’s leadership were gone, displaced by a firm and at times stubborn resolve to commit his government and his nation to whatever contributions of men and machines were needed to win the war. In the aftermath of the Canadian victory at Vimy Ridge on Easter Monday 1917, Borden abandoned his promise of no conscription and led the effort to pass the Military Service Act. With his Quebec support nearly exhausted that spring, he sought, and failed, to persuade Sir Wilfrid Laurier to join him in a coalition to enforce conscription. He persisted, much to the dismay of a sizeable portion of his caucus, and eventually crafted a coalition of Conservatives and Liberal Unionists which crushed the Liberal Party in the bitter election of December 1917. The political cost was enormous: the Conservative Party’s support in Quebec was destroyed and would not be recovered for decades to come. Moreover, Unionist support in western Canada was ephemeral and vanished at the first hints of peace.

Compulsion for overseas service was echoed by vigorous use of the powers of the state at home. The nationalization of the transcontinental railways was begun. Borden’s government regulated food and fuel distribution and controlled fuel prices and miners’ wages. It imposed a “temporary” direct tax on incomes, both personal and business. It forbade both strikes and lockouts. And, with the support it enjoyed from the Liberal Unionists, it reformed the federal civil service. Compared with the exercise of state power during World War II, the actions of Borden’s government in World War I were almost amateurish. In the context of the time, however, they were breathtakingly bold.

Borden’s most lasting contribution grew out of his deep commitment to the war effort and his long-standing belief that Canada had the capacity and was entitled to control its own external affairs in both peace and war. Dominion autonomy and the transformation of the empire into the new British Commonwealth of Nations were born of the Great War. Lloyd George provided the opportunity. Borden and his legal adviser, Loring Christie, seized it. Canada’s soldiers, Borden believed, had earned it. His duty, his responsibility to them and to Canada, was to achieve it. Recognition of Canada’s right to craft its own external policy, to have its own diplomatic representation in foreign capitals, to have full membership in the League of Nations, and to play a leading role in development of the Commonwealth were the rewards of Borden’s persistent campaign for equal status. General Jan Christiaan Smuts of South Africa, a strong supporter in London and Paris, told Borden in 1927, “You were no doubt the main protagonist for Dominion Status.”

Sir Robert Borden had not the magnetism of Laurier, the daring flair of Macdonald. He was an uncommonly reserved person for a national political leader, a man who believed that his often stodgy public persona was the country’s business but his private life belonged to his very close friends and family. He was, throughout his political career, less interested in politics than in policy. He was devoted more to his nation than to his party. His determination and commitment to lead Canada through the Great War made him the only Allied leader to stay in office throughout the conflict, an accomplishment of which he was very proud. Lloyd George called him “a sagacious and helpful counsellor” who was “always the quintessence of common sense.” Borden would have liked that.

R. C. Brown, Robert Laird Borden: a biography (2v., Toronto, 1975–80), provides a complete list of the manuscript and printed sources for the subject’s life and career. Among the more important published works are Borden’s Letters to limbo, ed. Henry Borden (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 1971) and Robert Laird Borden: his memoirs, ed. Henry Borden (2v., Toronto, 1938), and John English’s Borden: his life and world (Toronto, 1977) and The decline of politics: the Conservatives and the party system, 1901–20 (Toronto, 1977).

Cite This Article

Robert Craig Brown, “BORDEN, Sir ROBERT LAIRD,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/borden_robert_laird_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/borden_robert_laird_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Robert Craig Brown |

| Title of Article: | BORDEN, Sir ROBERT LAIRD |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | March 1, 2026 |